Fabric Object: Diana Agrest and Mario Gandelsonas

– Stan Allen, Beatriz Colomina, Michael Meredith, Jesse Reiser and Mark Wigley

The small exhibition Fabric Object, curated by Michael Meredith and exhibited at the Princeton University School of Architecture between 7th March and 3rd May 2024, brought together seven projects from the early career of Diana Agrest and Mario Gandelsonas, of Agrest and Gandelsonas Architects. Short texts written by the Princeton School of Architecture faculty: Stan Allen, Sylvia Lavin, Jesse Reiser, Tessa Kelly, Marshall Brown, Darell Wayne Fields, Anda French, Paul Lewis, Erin Besler, Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley were also included in the curation of the exhibition.

Michael Meredith writes about the Fabric Object exhibition:

There are seven projects, mostly unbuilt, all related to ideas of urbanism, presented through things made by hand. Drawings. Writings. What seemed important was to show an intimacy to their work, while also showing how impersonal it is. It may sound contradictory, but Agrest and Gandelsonas have always played with oppositional binaries. Individual-Collective. Building-City. Memory-Amnesia. Fabric-Object. Like the flip-flop reversibility of their axonometric drawings (think El Lissitsky Proun) architecture appears as something and an inversion of that thing. They love design. They love non-design. Architecture is autonomous. Architecture relies upon the city. And so on. Maybe this is because there are two of them. With two, and is inevitable. Or perhaps their work is simply a product of its time, a collection of 1968 Pre-Post-Structuralist desires (think Barthes, Saussure, Kristeva, Lacan, etc..) brought into Architecture, ideas like Language as a Model (and Speech as a Model and Text as a Model,) Dialectical Opposition, Semiotics, Typology, Rejection of Authorship/Individualism, and so on. If you read their descriptions of their own work, they will tell you what everything means. This as That. That as This. They construct complex thoughts and arguments with their work, but they will also tell you that it can never mean any one thing, there is always and.

Through three posts, Drawing Matter will revisit the seven projects from the early career of Diana Agrest and Mario Gandelsonas and the texts written by the Princeton School of Architecture faculty.

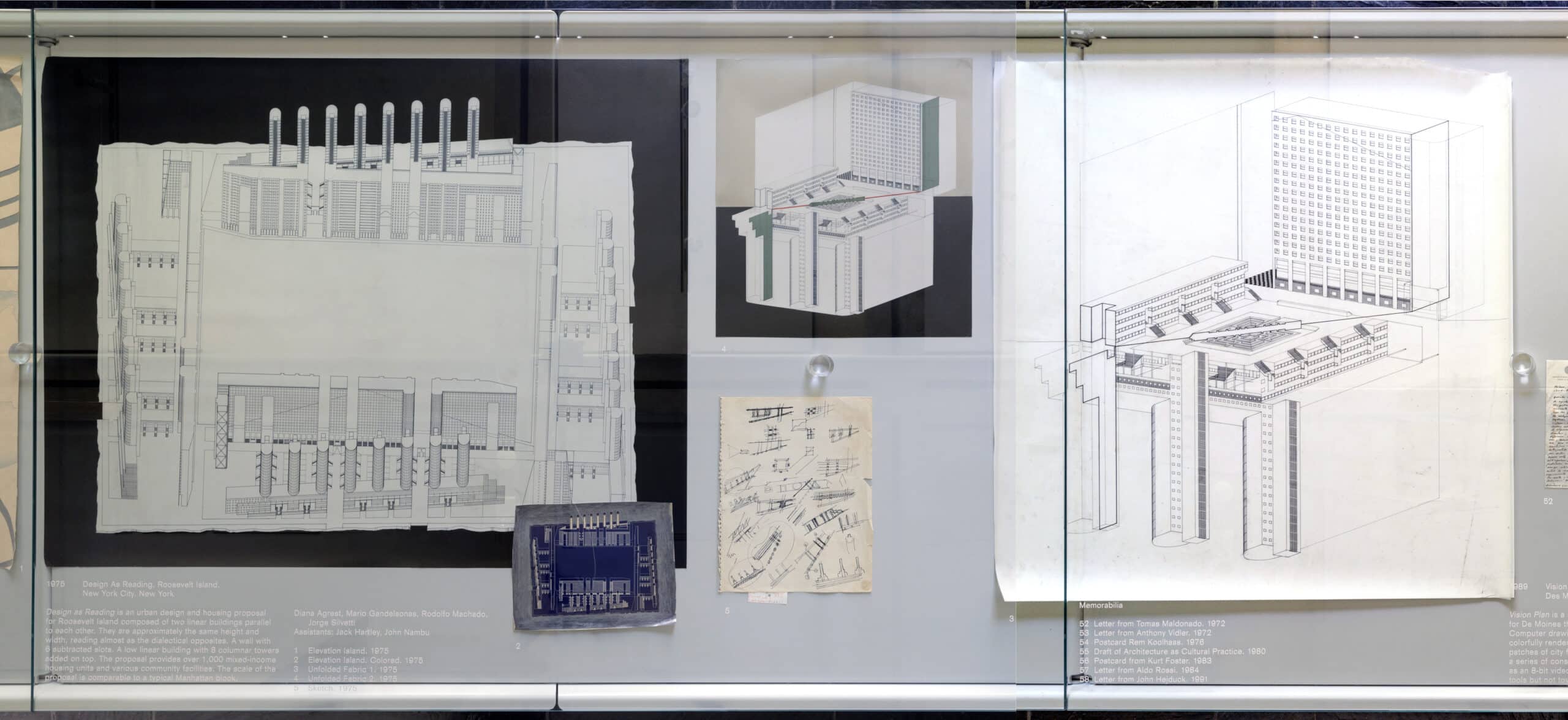

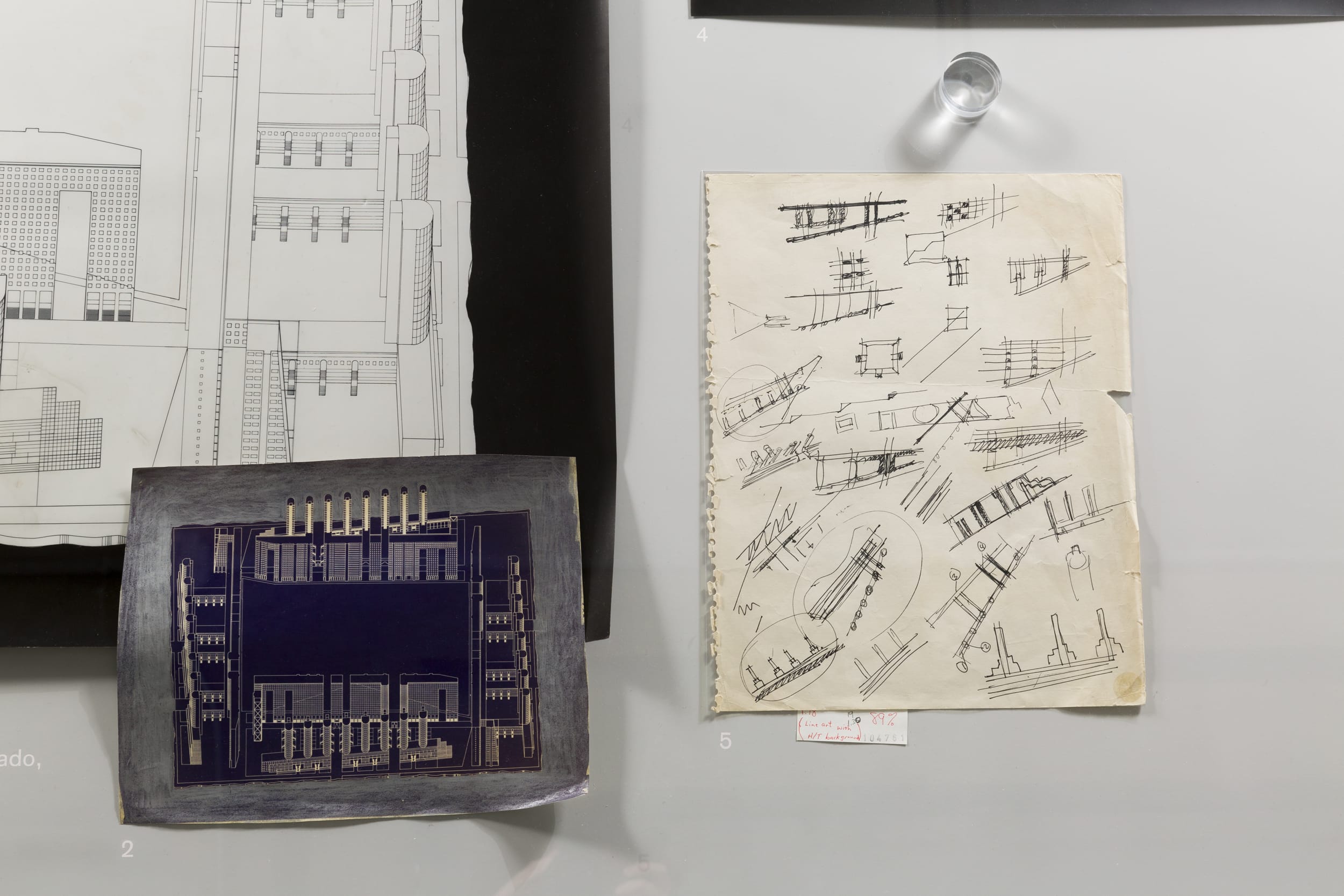

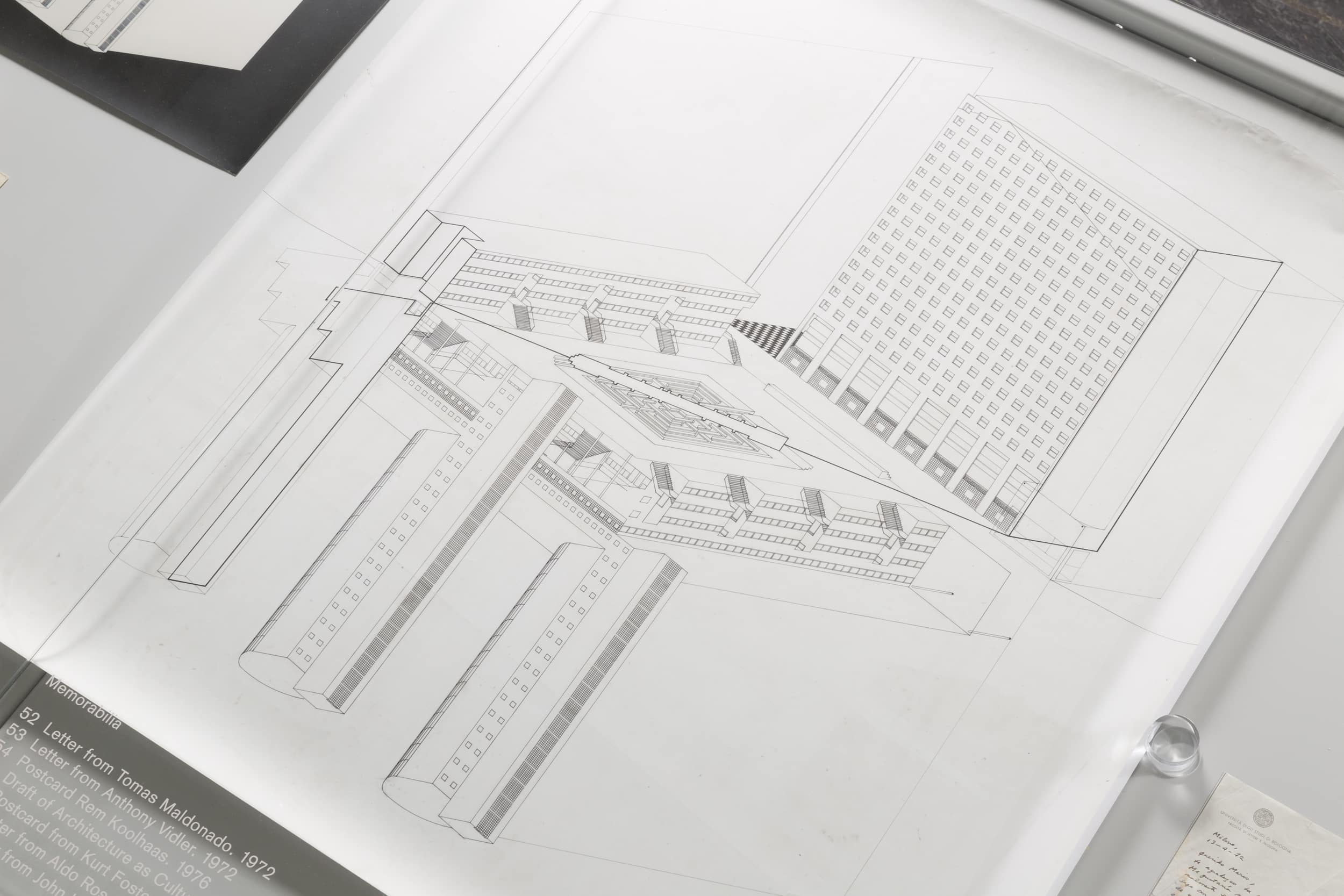

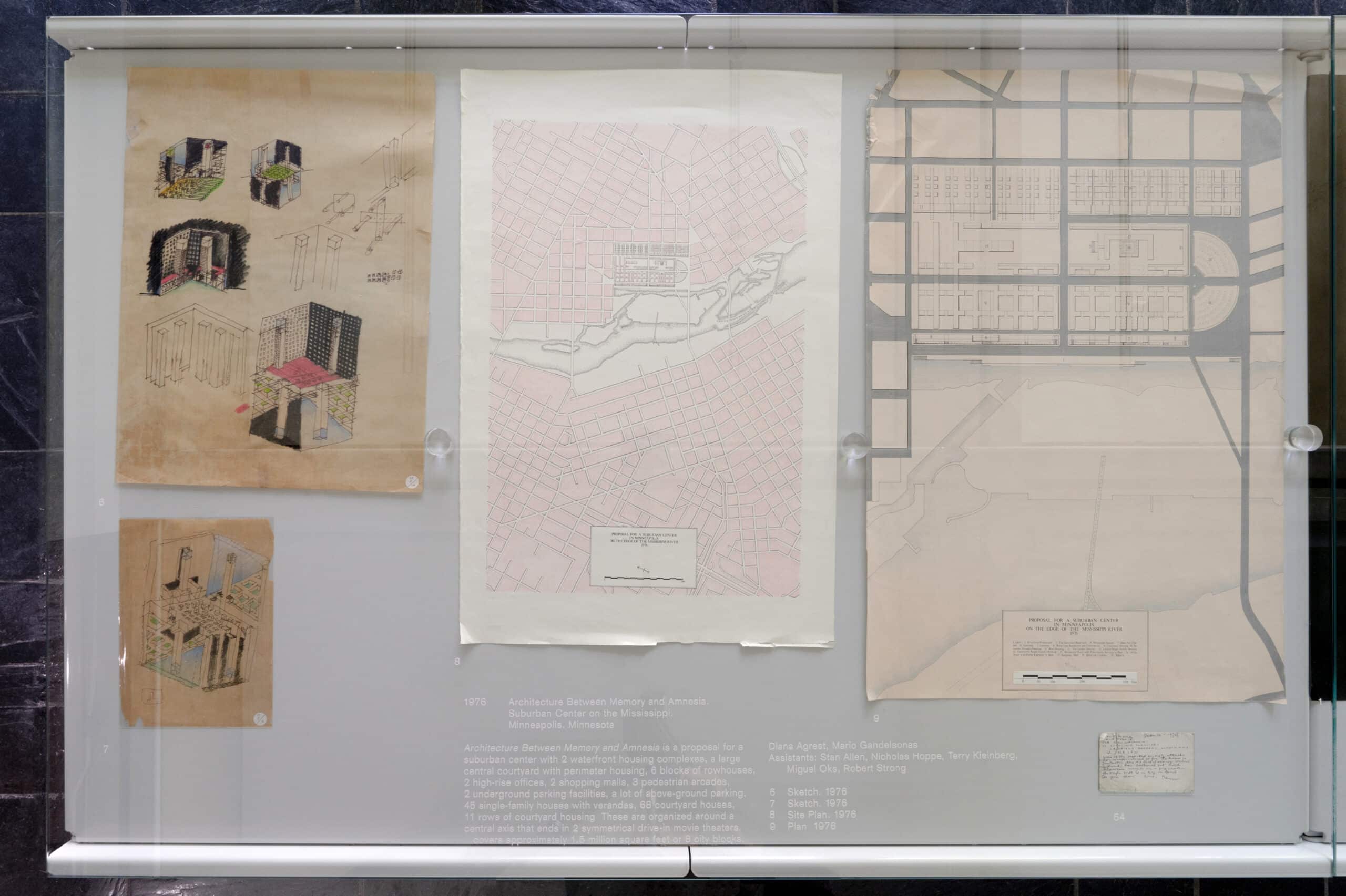

This first post presents the projects: Design as Reading, Roosevelt Island, New York City, 1975 and Architecture between Memory and Amnesia, Suburban Center on the Mississippi, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 1976 through Stan Allen’s, Jesse Reiser’s, Beatriz Colomina’s and Mark Wigley’s reflections.

In 1976 I was an undergraduate at Brown University by Stan Allen

In 1976 I was an undergraduate at Brown University, which had no architecture major. I was taking design courses at RISD, history of architecture classes at Brown and looking at other options. Peter Eisenman came through the school recruiting for the undergraduate program at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies—something like a junior year abroad, but in New York, which, in 1976, felt like a foreign country. I knew about Archigram, and thought about the AA. Or maybe I would just go to art school in Rome.

Somewhere, I’m not sure where (there were actual bookstores back then), I picked up a copy of L’architecture d’aujourd’hui No.186, ‘New York in White & Gray.’ Among the published entries for the recent Roosevelt Island competition, alongside works by Ungers and OMA, was a project by Agrest and Gandelsonas. I knew they taught at the Institute, and I decided this was where I should study.

In part, I was seduced by the drawings. Weird unfolded axonometrics that described an urban room complete with a labyrinth. Somehow, I thought of Borges. Four 90-degree axonometrics that showed different views of the project around an empty center: shot and counter-shot. An uncanny perspective that showed the view from Manhattan, the towers reflected in the river, the outline of a giant pediment inscribed into the façade of the housing behind. Everything was serial and repetitive, yet somehow familiar: recognisable fragments of Manhattan—towers, slab-like blocks, townhouses—remixed to create something new.

But I also knew, or intuited, that there was a sophisticated intelligence behind this formal language. I would later learn about typology, morphology, the architecture of the city and semiotic theory, in large part from Agrest and Gandelsonas. In this early work, inventive forms of representation, disciplinary knowledge, and elegant form-making converged, and the project remains a touchstone for me.

Of Memory & Amnesia by Jesse Reiser

Minneapolis might be the place, or it just as well might be one in any case.

Classical mnemonics made use of almost any word or thing as an aide memoire as long as it was striking enough to be summoned at will. Architecture was a favourite topos for this method, functioning as a rational scaffolding for a salient series, to recall anything, one merely had to take a stroll through an imaginary building.

The mapping of arbitrary signs onto measurable things as a means to understand the world resonated deeply with those who came of age in the late ’60s and struggled to come to terms with an alienating modernity first staked out by Einstein, Marx and Freud. Utopians and perennial outsiders by dint of their Jewish identity, being once bound to, yet yearning to be free from tradition, they fashioned a will to invisibility. To become universal—a mere human among other humans; free cosmopolitans.

The ’68 generation entered this process already two generations behind the first pioneers, in the intervening decades the ineluctable process of rendering everything solid into the air had done its work: the pure utopic artefacts of the first modernism, alas, had become the same as everything else: pitched or flat roofs no matter—all had been converted into a wasteland of physical, yet insistently spectral, signs that decoded promised and simultaneously denied meaning. To the initiated few this oscillatory state between matter and psyche elicited the kind of hysterical lightness of tony gallery openings; to common folk, it doubtless looked something like home. One might import a model; typology with Italian characteristics, that would mesh perfectly with the Jeffersonian grid, ordaining a universal degree-zero, a placeless place not unlike the Midwest’s projected and built ubiquity. A Minneapolis or some such place dreaming itself, begotten by someone somewhere—even by these architects—yet appearing found as if authored by nobody in particular.

No Position by Colomina Beatriz and Mark Wigley

Two grey towers rise up from a clearing in an urban maze. Both topped by a cube within a cube. Yet the nested cubes and connection with the ground of each tower are inverted between surface and frame. Same but different. A couple. Not touching but held together in a kind of prison yard within a labyrinth carved out of a single red material. Two monumental entrances lead to the towers but colossal steps prevent entry. An urbanism for buildings, not people, that is itself a single building housing an architectural couple.

Hard to imagine a more conservative project in the sense of architecture recursively turning in on itself. It’s a manifesto of the late ’70s repeatedly published and exhibited alongside projects labelled ‘rational’ and ‘autonomous.’ A manifesto defined by a single axonometric drawing, often cut into pieces when published, and eventually surrounded by perspectival vignettes of a haunted post-human landscape. Three years of work on one drawing accompanied by a text describing it as a mutually transformative juxtaposition of European urban order and American suburban disorder that dissolves both architectural languages—a text that was finally handwritten into the drawing itself.

Yet the architectural couple also undo their architectural twin. The very first published image of the project represented ‘The Future of Architecture’ on the cover of the May 1977 Progressive Architecture. The unnamed uncredited drawing inverts the towers. Two becomes four. Solid becomes void. Air becomes building. Inside becomes outside. Dense red urbanism becomes a floating folded surface. This drawing technique was already used in the Roosevelt Island competition of 1975, done in collaboration with another Argentinian couple, like the initial competition phase of this project in 1976. Lissitsky invented the technique in 1927 to capture the destabilizing disorienting anti-architectural ambition of his radical Kabinett der Abstrakten. 50 years later, architects use it to repeatedly destabilize their own construction in four such ‘intersection’ drawings. The towers are endlessly inverted and turned inside out in a kind of suprematist vertigo that is never discussed. This is a self-undoing manifesto whose very point is to paradoxically refuse to take a position.

Diana Agrest is a Professor of Architecture at The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture of The Cooper Union for Advancement of Science and Art. She is a founder and principal of Agrest and Gandelsonas Architects in New York, while she also develops her own individual projects.

Mario Gandelsonas is an architect and theorist whose specializations include urbanism and semiotics. Gandelsonas is a Professor of Architectural Design at the Princeton University School of Architecture, and with Agrest, he is a founding partner of Agrest and Gandelsonas Architects.

Michael Meredith is a Professor of Architectural Design at the Princeton University School of Architecture. Along with his partner, Hilary Sample, Meredith is a principal of MOS, based in New York. His writing has appeared in Artforum, LOG, Perspecta, Praxis, Domus, Harvard Design Magazine.

Stan Allen is the principal of SAA/Stan Allen Architect and former Dean of Princeton University School of Architecture. From 1989–2002, Allen taught at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation and was also the Director of the Advanced Design Program.

Jesse Reiser is a Professor of Architecture at Princeton University and has previously taught at various schools in the US and Asia, including Columbia University, Yale University, Ohio State University, Hong Kong University, and the Cooper Union. He is a partner of Reiser + Umemoto with Nanako Umemoto.

Colomina Beatriz is an architectural historian and theorist who has written and curated extensively on questions of architecture, art, technology, sexuality, and media. She is the Howard Crosby Butler Professor of the History of Architecture, the founding director of the Media and Modernity program at Princeton University, and the Director of Graduate Studies (Ph.D. program) in the School of Architecture.

Mark Wigley is Professor of Architecture and Dean Emeritus of the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (GSAPP) at Columbia University. He is a historian, theorist, and critic who explores the intersection of architecture, art, philosophy, culture, and technology.