Futures of the Architectural Exhibition (2023) – Review

In recent decades, architectural exhibitions have emerged as a principal site for advancing architectural discourse within the design professions and as a primary stage for drawing interest in public audiences to architecture. Many architectural exhibitions have proven the medium an intellectual leaven for new generations of discursive content and styles, from Paolo Portoghesi’s ‘Presence of the Past’ at the 1980 Venice Architecture Biennale to Joseph Grima and Sarah Herda’s debut of the largest architecture and design exhibition in North America with ‘The State of the Art of Architecture’ at the 2015 Chicago Architecture Biennial.

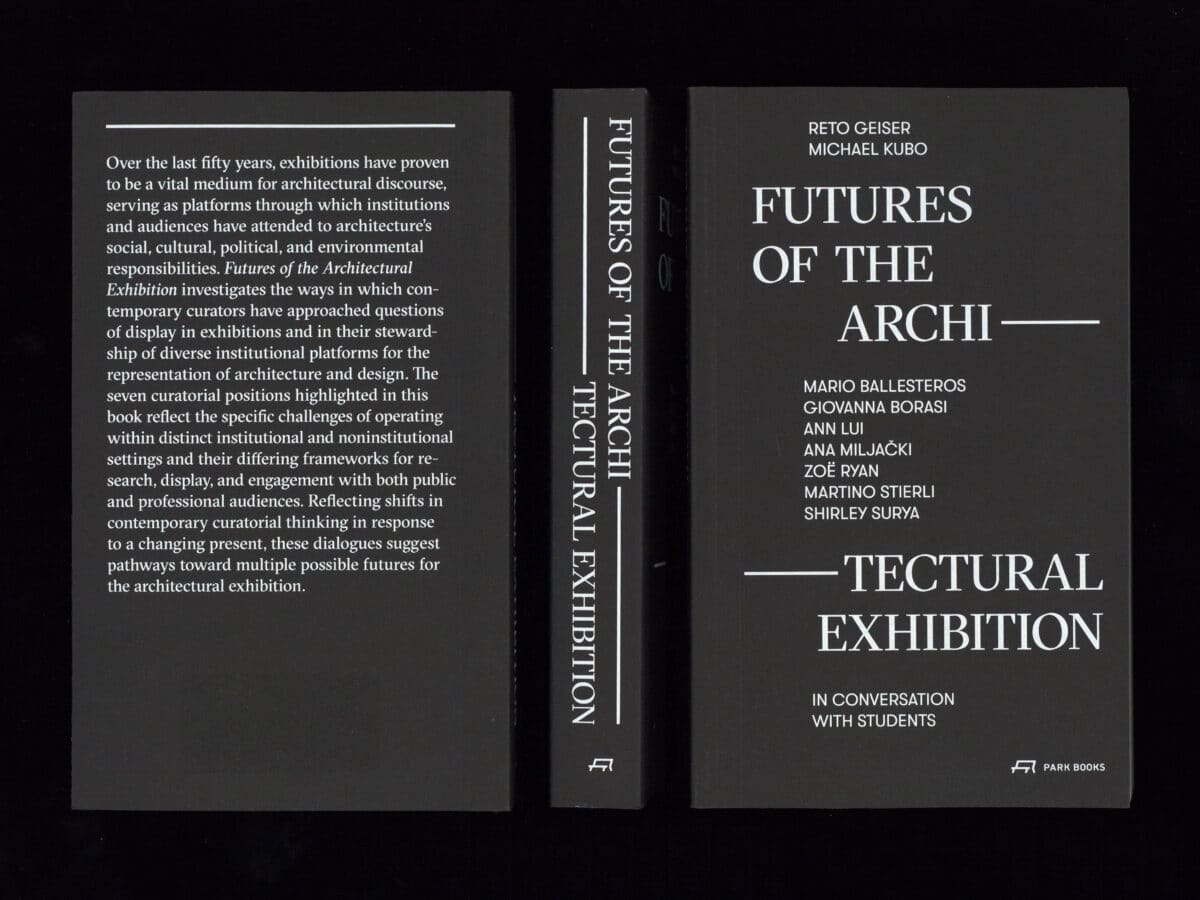

This awareness of an exhibition’s immediate impact on shaping architectural discourse weighs heavily in Reto Geiser and Michael Kubo’s new book Futures of the Architectural Exhibition, published by Park Books. Along with Geiser and Kubo’s prelude, ‘Exhibitions as Discourse’, the book is organised as a collection of interviews with seven of contemporary architecture’s leading curators and exhibition designers. Each conversation is a well-edited discussion with multiple discussants, including students and invited faculty from Rice University and the University of Houston, written in a single voice. Futures of the Architectural Exhibition provides a rare look into the recesses of exhibition practice with some of the world’s premiere art and architecture institutions.

Although one interviewee is an architect, this book is not about architects curating exhibitions of their own designs. Rather, it’s about the inherent challenges and opportunities for curators in displaying the work of architects. Each interview captures a range of approaches and modes of curatorial practice in architecture from around the world. And their discussions follow similar themes: the insightfulness of young people and working with students; art and digitalisation (admittedly influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic); the question of displaying canonical versus non-canonical work, among other things. But by far the book’s predominant theme is the curatorial intent to expand, e.g., audiences, collections, staff, discourse, exhibition programmes, and disciplinary boundaries.

This happens in several ways:

In ‘Shaping Positions,’ Zoë Ryan discusses her vision to broadcast architecture and design culture to nondisciplinary audiences at the Art Institute in Chicago and in her current position at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia. Ryan discusses the responsibility of museums to educate people about architecture, the necessary distance between architects and curators, and her realisation at a young age about the possibility for art to reflect on society at a particular moment in time.

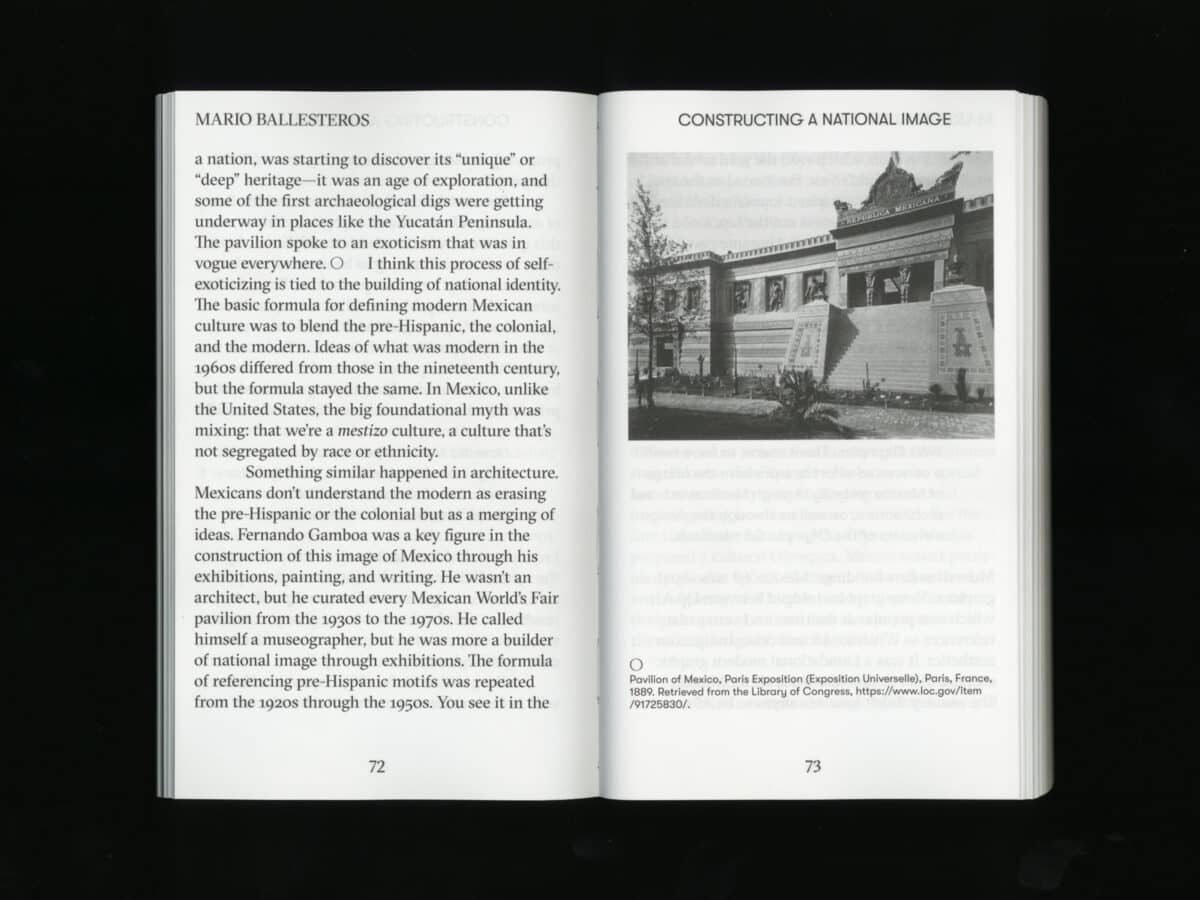

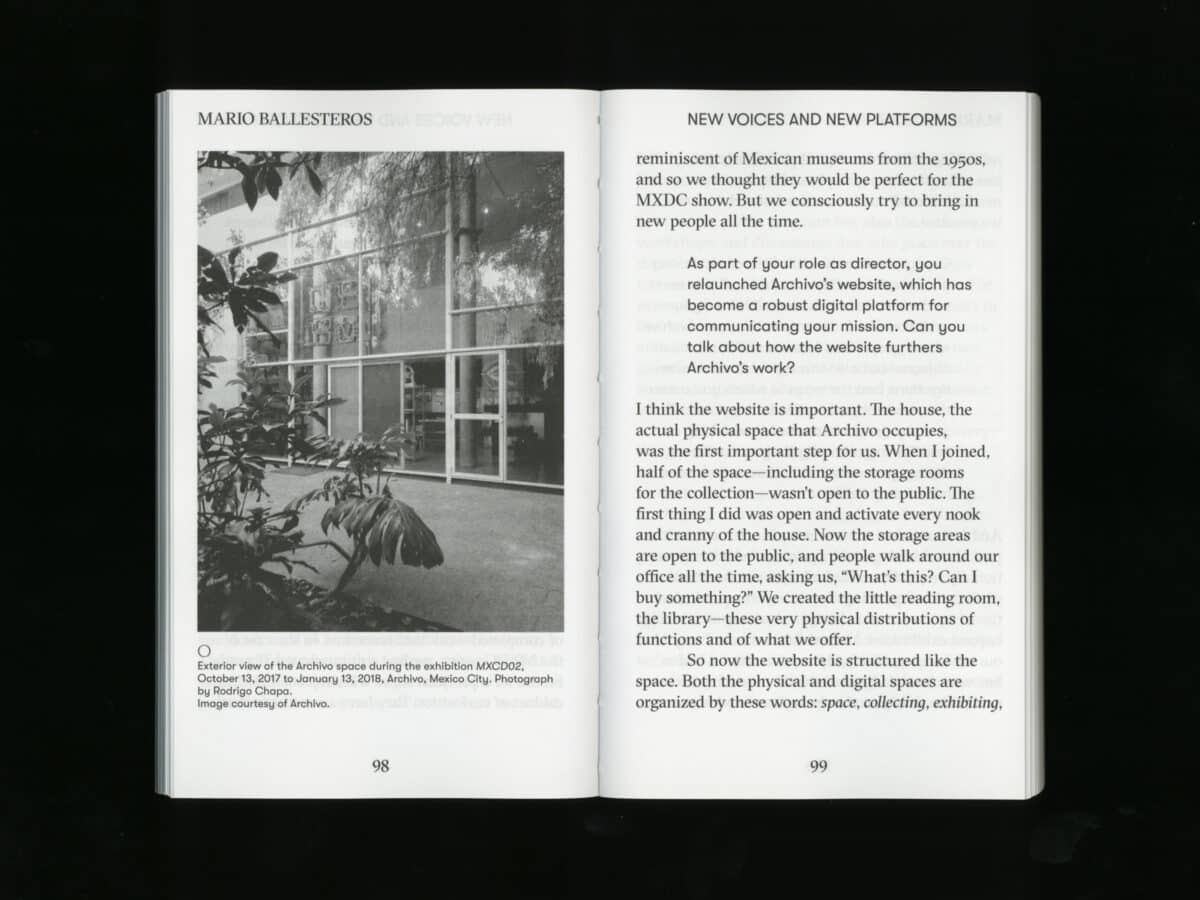

In ‘Exposing the Margins,’ Mario Ballesteros reflects on his time as Director and Chief Curator of Archivo Diseño y Arquitectura in Mexico City, specifically how his exhibitions displayed alternative modes of object collection to the more conventional institutional categories of exhibiting and collecting. Ballesteros discusses the role of international exhibitions in shaping ideas about indigenous, colonial, and modern architecture in Mexico and the myth of mestizo culture.

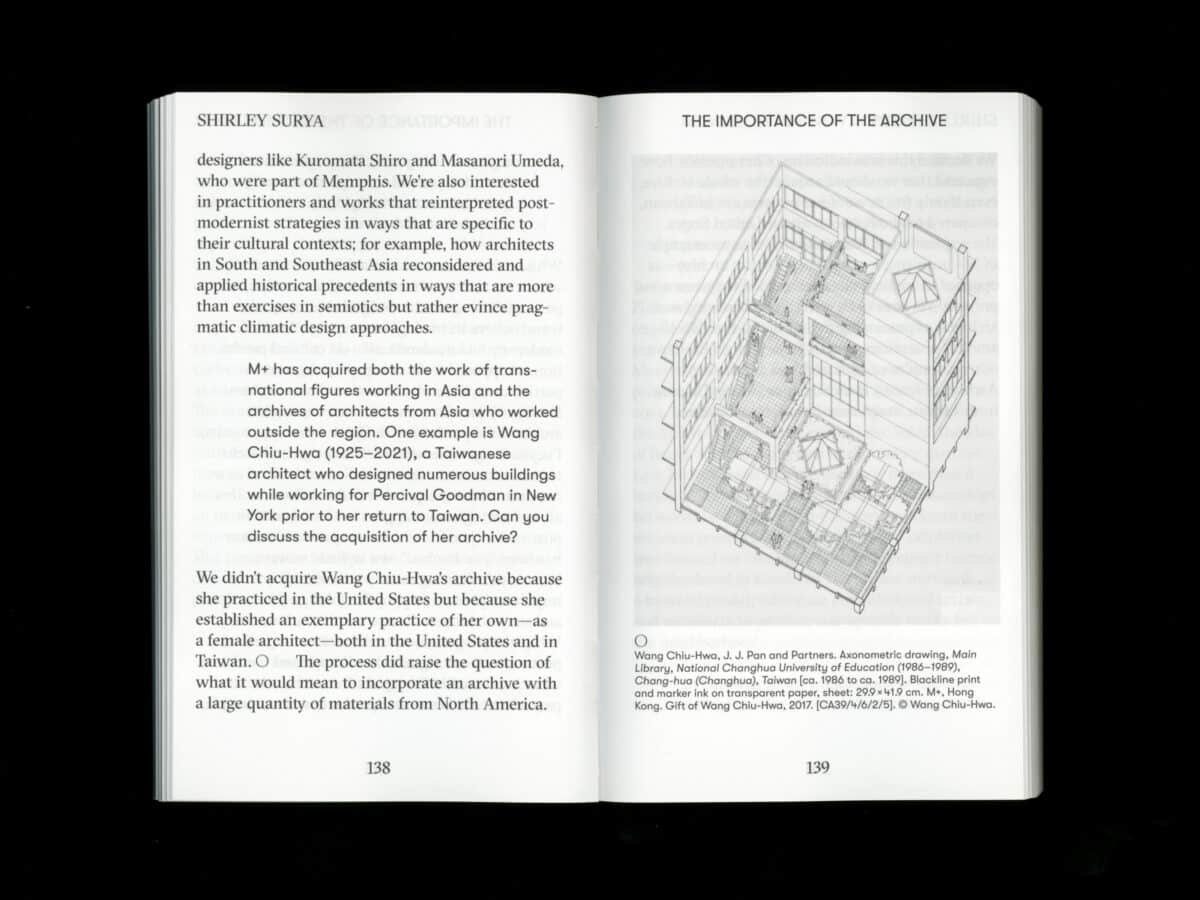

In ‘Curating as Collection-Building,’ Shirley Surya reveals the arduous process of building a collection as curator of design and architecture at the newly opened M+ in Hong Kong. She reveals the complicated process of persuading others that M+ should acquire the entire Archigram archive (they were successful), and the geographic porosity of Hong Kong as a cultural gateway to China, Asia, and the rest of the world. At M+, this idea of porosity extends to acquisition practices as well: ‘We’re porous to both the canonical and the non-canonical,’ Surya says, ‘we can’t engage one without the other.’

In ‘The Exhibition as Research,’ Martino Stierli grapples with the legacy of his predecessors and the institutional significance of his position as Chief Curator of Architecture and Design at MoMA. As a scholar, Stierli discusses his idea of photography as a hybrid category between documentation and the artistic interpretation of a building. As a curator and researcher, he rethinks curating as a form of collaborative research ‘in public,’ and reflects on the trend of exhibitions that focus on underrepresented movements in architecture.

In ‘Museum Work and Museum Problems,’ Director of Montreal’s Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) Giovanna Borasi explains the intent of their exhibition ‘Besides, History’ to address how contemporary architects reckon with certain historical figures and moments in history. Borasi contemplates the changing ways that people experience exhibitions and shares her belief in the need for institutions like the CCA to address society’s most pressing questions.

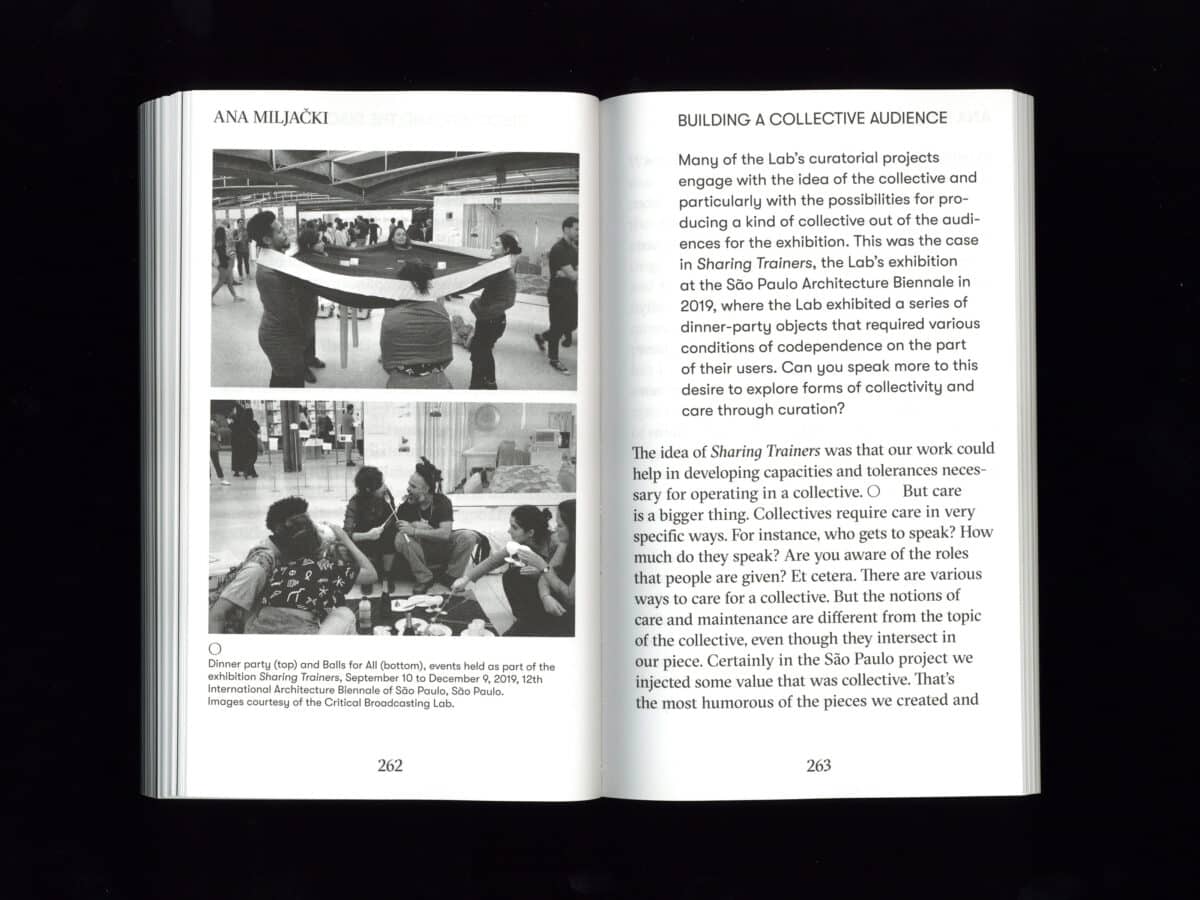

In ‘Tending to Discourse,’ Ana Miljački, Associate Professor of Architecture at MIT and Director of Critical Broadcasting Lab, comments on the problematic aspects of contemporary architectural discourse, and how being critical can resist the notion of discourse as a catchall term where louder means more important. Miljački’s Lab at MIT expands disciplinary discourse by connecting it with political agencies and issues of labour, bureaucracy, and intellectual property.

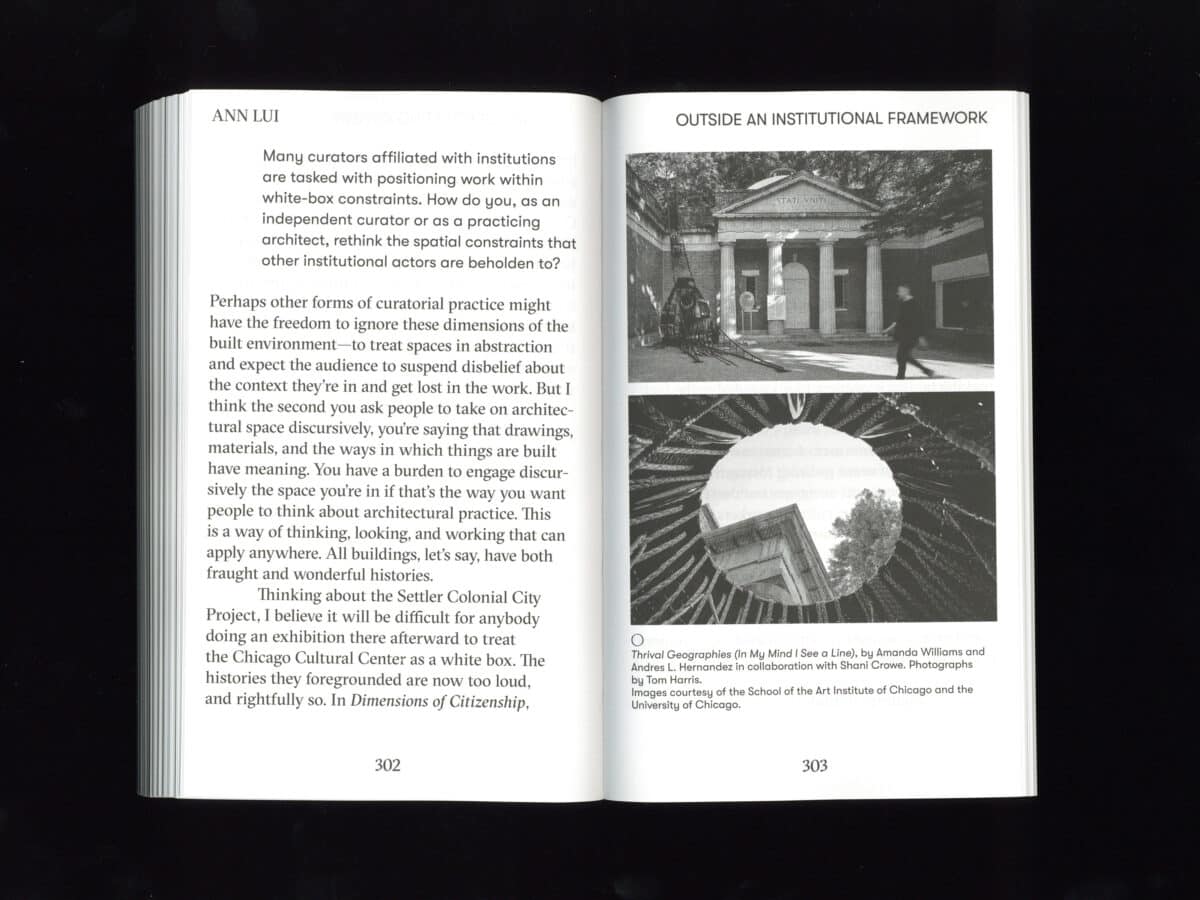

In ‘Curating Collective Space,’ Ann Lui reflects on the art historical and institutional definitions of curatorial practice as a specific discipline and her role in it as an architect and founding principle of Chicago-based Future Firm. As a practitioner and curator, Lui discusses ‘the tension between valuing disciplinary expertise and expanding the boundaries of the discipline within architectural practice,’ that is, between depth of knowledge and breadth of experimentation.

This intent to expand disciplinary boundaries, reach more audiences, and broaden exhibition content is conveyed in each discussion and it’s not difficult to see why. In the nearly three years since the George Floyd protests, countless museums and cultural institutions have reexamined themselves to earn more trust from communities and reconcile with their histories. The very medium of exhibitions are, after all, steeped in colonial genealogies, from ‘cabinets of curiosities’ to dioramas. Futures of the Architectural Exhibition is an insight into the way several institutions have approached this reexamination by diversifying their staff, permanent collections, audiences, and exhibition programmes. But these efforts shy away from the explicit association of curatorial practice with imperialism, colonialism, and racism.

In their newly published book Manual of Anti-Racist Education, WAI Think Tank calls for alternative curatorial practices that finds platforms outside the institutions that construct the hegemonic architectural narratives that are baked into the acquisition practices of many institutions. When asked whether it was a goal to decolonize the canonical European and North American objects in M+’s collection, Surya responded, ‘We don’t use the word “decolonising” or the term “revisionist”, as these can be misunderstood as purely oppositional and risk creating another form of centring and marginalisation.’ The ‘Museum Work and Museum Problems’ conversation shows that M+ is concerned about building a collection not for prestige but for knowledge and future research. But where are the architectural curators who are not only departing from the problematic infrastructures of cultural institutions but also creating discourses that challenge those same institutions?

Perhaps MoMA provides one answer with their recent exhibition ‘The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonisation in South Asia, 1947 – 1985,’ but this is part of a larger departmental goal to challenge, as Stierli says, ‘the implicit biases of our Eurocentric collection by paying more and sustained attention to architecture and designers of colour, to women artists, and to work from outside the Western world.’ Yes, the goal to stage voices of historically less visible movements and geographies is needed. Each discussion in Futures of the Architectural Exhibition speaks to desires for disciplinary expansion, reconciliation, and more just institutions. But, as StikeMoMA states in their framework, the political economy of the art system itself is predicated on hegemonic narratives, written on property, and governed by gatekeepers and canon-makers. How far do disciplinary boundaries have to expand, how diverse and global do exhibitions need to become to fix that?

Reto Geiser and Michael Kubo Futures of the Architectural Exhibition (2023) is published by Park Books. Copies of the book can be purchased here.

Paul Mosley is assistant professor of architecture and urban design at Kent State CAED.

Notes

- See, for example: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/museum-dei-plans-2022-2161690 (accessed 1.3.23)

- See, for example (paywall): https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/28/arts/design/raphael-montanez-ortiz-el-museuo-del-barrio.html (accessed 1.3.23)

- See: https://www.strikemoma.org/ (accessed 1.3.23)