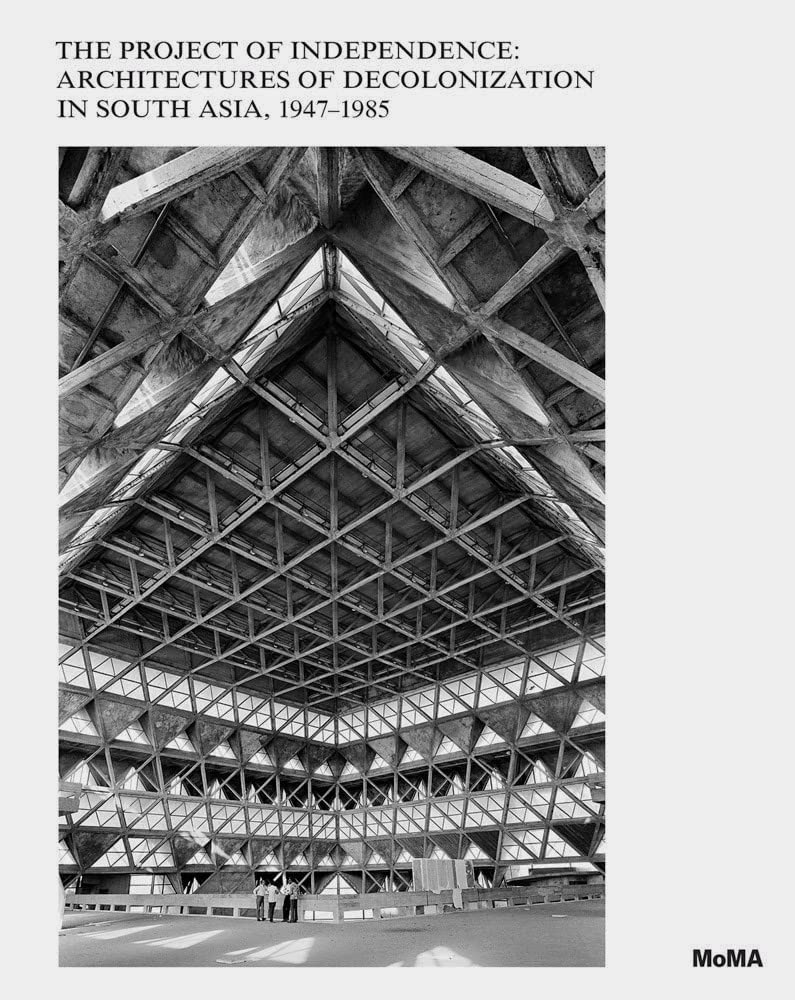

The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947-1985 (2022) – Review

“The history of modern architecture is the history of its exhibitions,” states the introduction of the anthology ‘Exhibiting Architecture’, [1] and it is hard to deny the central role of exhibitions in the writing of the canonic and the public history of architecture. Yet the exclusionary nature of the history that has so far emerged out of this formulation is equally hard to miss. If someone had told me that there would be an exhibition on the decolonization of South Asia at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York when I was writing my dissertation and teaching my first seminars on postcolonial theory at Columbia University and Pratt Institute years ago, I would have said they were hallucinating. In those days, a very common term was “postcolonial junk.” This was frequently and publicly employed by scholars of many generations, through which they established a superiority over those who worked on “non-western” topics. At that time, the exhibitions at MoMA featured white male contemporary architects and gave them an even bigger boost in their careers. In this context, any review should first acknowledge and celebrate the distance MoMA has travelled both literally and metaphorically to prepare the exhibition ‘The Project of Independence’ (20 February – 2 July 2022). One therefore wonders about the reasons for the silence of some and the hostility of others that burst out as soon as the show opened, some of which trivialised the exhibition’s global reach (in a trend that reminds me of the idiom ‘Empire Strikes Back’), while others perpetuated the received scepticism about MoMA’s ability to overcome its own whiteness. This reception foreclosed the appreciation of the political and cultural struggles of professionals in Bangladesh (East Pakistan), India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka (Ceylon), as well as the sheer beauty and quality of their works before our eyes.

Given the relative frequency that work from Latin America, particularly Brazil, appeared in the galleries of MoMA when the institution was forming its own definition of modernism,[2] it is fair to say that the exhibition on the history of South Asia is the museum’s first step out of its geographical comfort zone. This choice seems appropriate, since the Independence period of India, especially, has held a central place in the field of postcolonial studies and the diverse set of issues discussed by the Subaltern Studies Group, Gayatri Spivak, Dipesh Chakrabarty, Arjun Appadurai, and Homi Bhabha, among others, as well as the architectural historians who participated in the debate, such as Kathleen James Chakraborty, Vikramāditya Prakāsh, Sibel Bozdoğan, Gülsüm Nalbantoğlu and C.T. Wong, among others.

A review of the catalogue of The Project of Independence, edited by curators Martino Stierli, Anoma Pieris and Sean Anderson, warrants a discussion on the history of modern architecture as written through exhibitions. The tight relation between the beginnings of architectural exhibitions in Europe and the construction of the idea of a public sphere and public debate about architecture is well recognised. The former MoMA curator of modern architecture and design, Barry Bergdoll has demonstrated that exhibitions have served to make a self-conscious modern architecture within a critical discourse since the Enlightenment [3]. Let’s be specific, however, about the different types of histories constructed or subverted through exhibitions. These include: official history (how could an exhibition oppose the official but reductive histories written by the rulers of nation-states including those exhibited and exhibiting?); architectural history (what is the role and responsibility of powerful institutions such as MoMA for the production of new knowledge in architectural history?); and public history (given that exhibitions create the platform where architecture’s public history is manifest, could a show shift the public opinion towards a more just view of countries in South Asia, some of which have been described as ‘threats to Western civilisation’?)

The Project of Independence inherits the word “South Asia” in its title from area studies and chooses the word “decolonization” – now an overused and blurred concept – to frame its contours as the lands that gained independence from the British Raj in 1947-48. Rather than repeating the categories of official history, it takes up the challenge of presenting together the four countries that came out of the colonial period, even though these lands have been violently partitioned due to the legacy of both colonisation and nation-building during decolonization. This curatorial strategy chooses to undo the Partition intellectually by refusing to present the four countries separately in a move that also results in the disavowing of the violent histories against, between and within them, as I will come back to below. Similarly, the catalogue is divided into four parts that conflate national territories. These are: the co-curators’ articles; a set of contemporary photographs by Randhir Singh; short essays by established architectural historians in the field; and detailed visual representations of seventeen projects accompanied by the curatorial team’s explanations for each. These, along with the publication of drawings and photographs collected and produced specifically for the exhibition, make the catalogue an extremely significant resource for architects and historians alike.

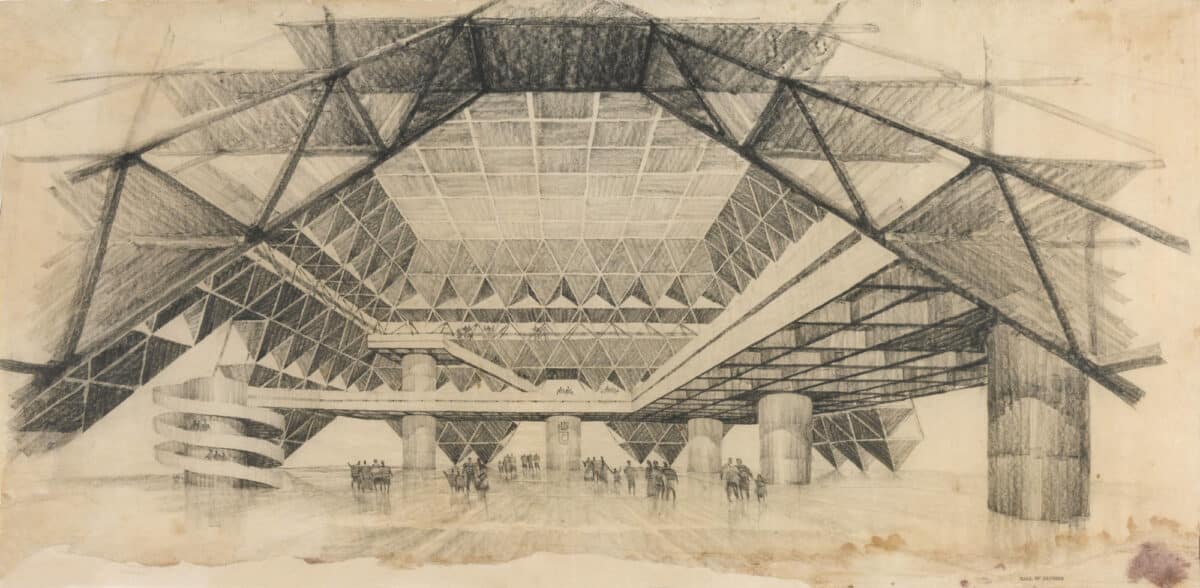

One of the main intentions of the curators is to refute the common judgment that post-war developmentalist modernism in Bangladesh (East Pakistan), India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka (Ceylon) was simply a neo-colonial imposition by European architects. Lead curator Stierli’s essay focuses on the role of reinforced concrete in the immediate postcolonial era by comparing it to analogous practices in the Global South, debunking the common narrative that its use outside Europe and North America was simply a matter of diffusion and imitation. Stierli not only exemplifies striking modernist buildings made of concrete, but also forefronts the unique labour practices and construction processes used and a globally connected but India-specific history of this modern material emerges out of the rift between Nehru’s and Gandhi’s different visions for India’s industrialisation. Contrary to common assumption, Stierli insists that “Chandigarh’s raw exposed concrete thus stands less for a neocolonial gesture enacted by a foreign architect and more for the process of decolonization that the nation was embarking on”[4]. It is time to acknowledge the emergence and advancement of modernism as a global process rather than maintain the assumption of centre to periphery dissemination. But an additional message rises from the MoMA exhibition: the argument that the specific trajectory of modernism that the institution has championed for years was also a decolonizing force.

Co-curator Pieris’s essay focuses on university campuses as a globally prolific post-war programme employing influential figures like Achyut Kanvinde, Doxiadis Associates, Balkrishna Doshi and Muzharul Islam. Pieris demonstrates that brutalist modernism became the language through which a new generation of architects expressed their independence from the British colonial regime, which had exploited traditional forms with Orientalising moves, as well creating distance from their religious signifiers. Reinforced concrete makes the most frequent appearance in both the museum and the book. Peter Scriver and Amit Srivastava’s essay also underscore the role of industrialisation in infrastructure, housing and tourism, albeit in a way that emphasises the continuities with the colonial regime more than the discontinuities. Kazi Khaleed Ashraf’s essay turns attention to the exceptional reinforced concrete single-family houses with their frame structures that enabled the use of passive cooling techniques, such as covered outdoor spaces and cross ventilation. By virtue of this “sheltered openness,” Ashraf shows, reinforced concrete came to be perceived as the suitable modern material for the climate-specific concerns of the subcontinent, while eschewing the typology of the bungalow.

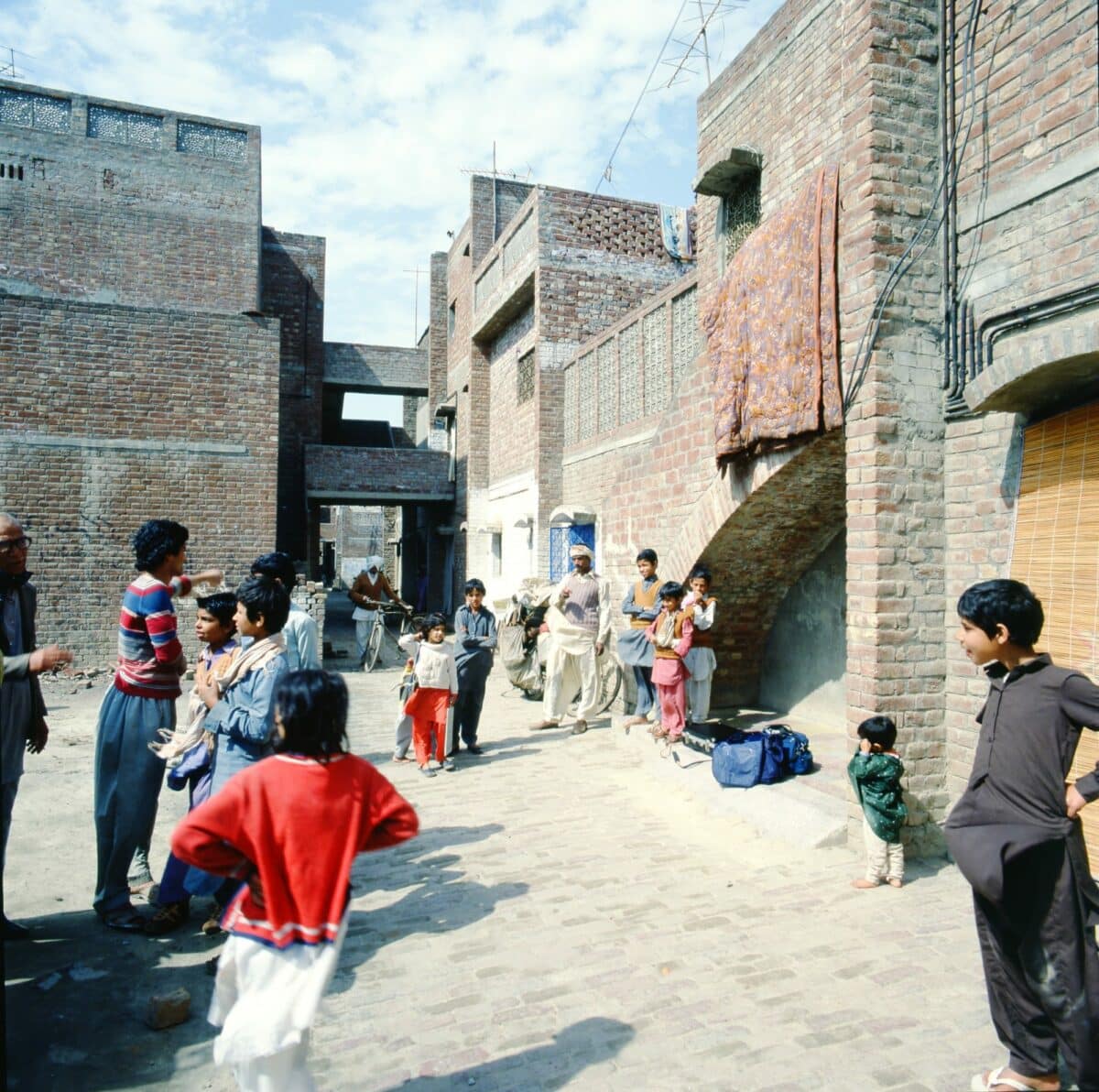

In addition to translations of reinforced concrete, the scholars’ essays bring a range of issues to the fore. While Partition as the violent legacy of British imperialism makes almost no appearance in the exhibition, its architectural consequences are addressed in the catalogue in Nonica Datta’s essay, where she discusses Otto Königsberger’s and Doxiadis Associates’ projects for the resettlement of refugees after they were displaced due to Partition. Rahul Mehrotra also brings up the topic of housing as the daunting task of settling large numbers of families in a short time to mitigate informal settlements in the 1970s. He reiterates the importance of new typologies for low cost, participatory or low-technology housing projected by well-known architects such as Charles Correa, Balkrishna Doshi, Raj Rewal and Muzharul Islam.

Farhan Karim’s essay demonstrates that architectural education throughout the subcontinent mostly followed colonisers’ protocols in establishing a professional autonomy for architects, but nonetheless created platforms that “offered a productive ambivalence that oscillated between contested ideas about the possible trajectories of post-Independence modernisation and postcolonial self-consciousness”[5]. Devika Singh’s essay brings to the fore the agency of media – spanning from generalist newspapers to specialised magazines – and the variety of outlets in the subcontinent for architecture’s self-reflection. She focuses on the legendary Marg and gives due acknowledgment to the Ceylonese architect Minnette de Silva, one of the two women to whom the MoMA exhibition pays due respect, along with Yasmeen Lari. Prajna Desai’s essay also forefronts de Silva and Lari and contests the interpretation of theirs and others’ work simply as an offshoot of “tropical modernism”– a colonial discourse that the Architectural Association in London extended into postcolonial times. Desai suggests that many leading architects in the region, including Geoffrey Bawa and Correa, stood out by virtue of their sensibility in integrating nature and landscape into the built environment.

Of particular note is Saloni Mathur’s essay, which explores the continuity between the fields of design and architecture. By focusing on overlapping schools, individuals and ideas it reveals the role of traditional crafts in the making of modernism in South Asia, and therefore demystifies, once more, common Eurocentric assumptions. The figure of Gandhi and his spinning wheel serves as a potent image of not only nationalist struggles but also translations that the common narrative of global dissemination obscures. Mathur suggests that the curricula and emphases in design schools serve as a counterpoint to the developmentalist paradigm of the 1960s and 1970s: “In contrast to the privileged role of design in industrial development, participants in this milieu often advocated a socially responsible practice of design that prioritised poor communities, local traditions, inexpensive materials, and indigenous skills”[6].

Another running theme in the exhibition is the threat of erasure due to the lack of appreciation for these buildings in architectural and official history. Pieris mentions the stigmatisation of many of the exhibited buildings and discusses the turn to what came to be known as regional or vernacular forms due to an “antipathy toward Western domination and intolerance of seemingly foreign aesthetics [that were] inflamed by the residual anti-colonial sentiment that the legacy of British rule still provoked”[7]. The exhibition alerts us to the recent demolition of some of these exceptional buildings, including Raj Rewal and Mahendra Raj’s Hall of Nations, as they fit neither the myth of ancient temples that are perceived to be worth preserving, nor the techno-enthusiasm of smart cities that are deemed to be more advanced. In this context, Mrinalini Rajagopalan’s essay on the predicaments of preservation gains particular importance, also because she implicitly criticises MoMA’s emphasis on “genius authors” that results in preservation practices that are “hopelessly entangled with colonial pasts”[8]. Focusing on the preservation debates around the Ena de Silva House, Kamalapur Railway Station and Hall of Nations, Rajagopalan asks instead: “Could Kamalapur Railway Station be reimagined from the perspective of the rural migrant arriving at the busting metropolis of Dhaka for the first time? Is it possible to write an architectural history of modernism from the viewpoint of the many Bangladeshis who passed by the station as they left for Malaysia, Dubai, or Abu Dhabi…?”[9].

In sum, these essays cover a diverse set of issues including planning, housing, building materials, labour, landscape, education, media, artefact design and preservation, and thereby help us see the architectural world beyond the conventional collectable artefacts that fill the museum’s galleries, such as impressive drawings, beautiful photographs, and well-crafted models. In this sense, MoMA acts as an informed collector for the catalogue, rather than a sponsor of new research. These short essays by credible experts in the field provide overviews of their own (and others’) work. They point new readers to proper references, but do not necessarily add substantial new scholarly knowledge to the field. Nonetheless, they break loose from the boundaries of the modern art museum that fetishises the object over the governing powers, production protocols, habitants and alternative media that allow us to understand the object.

Despite its conscious curatorial and editorial strategies to overcome national territorialising, the exhibition reproduces the Partition at many moments. India dominates the museum’s galleries and the catalogue’s pages, while Pakistan is trivialised – probably the result of underestimating the unfortunate but the very real dividing role of Partition and expecting too much from photographers and scholars of India in their ability to access Pakistan and Bangladesh. Sri Lanka (Ceylon) steals and shines on the stage, so to speak, (if we compare the number of inclusions from this country to the size of its territory), but the conditions that prepared the brutal civil war and ethnic conflicts during this time make no appearance. As I am writing these pages during the deadly floods that devastated Pakistan, I am reminded one more time that the global concrete utopia has created a climate Partition.

MoMA’s exhibition pays due acknowledgement to multiple makers of modernism including citizen and invited foreign architects, women professionals, construction workers and other labourers. However, the curatorial standards that determine what is collectable still narrows down our understanding of South Asian modernity. These standards highlight the importance of buildings and spaces that were designed through media that the museum considers valuable and displayable, such as visually striking plans, sections, freehand sketches, models, and artist photographs (these include construction photographs, such as Jatiyo Sangsad Bhaban’s magnificent panorama of National Parliament of Dhaka designed by Louis Kahn, and completed by David Wisdom & Associates). However, this choice simultaneously obscures all those that were not produced by professional architects with diplomas, or collected by powerful archives, and therefore amounts to a tiny portion of the built environment in the subcontinent, not to mention the fact that this decision results in the representation of the elite’s living spaces in a very caste-based society. One is reminded of Gayatri Spivak’s article “Can the Subaltern Speak,” where she both joined the scholars who advocated for studying the subaltern to understand postcolonial India, and at the same time exposed the challenges of this task because of the evaporation of a subaltern’s voice between the competing pressures of the British colonisers and the Indian national elites [10]. With this exhibition, MoMA gives voice to national elites but not necessarily to subalterns, despite the inclusion of low-cost housing, because only designers are fore-fronted. This also means that MoMA’s global and postcolonial architectural history is quite different from the same intellectual struggle in literary theory and critical studies, not to mention architectural history, whose research has been undertaken in universities.

MoMA has done its part by employing its own perception of display-worthy artefacts of modern architecture and expanding its geographical scope in order to participate in the writing of a global history where multiple makers from around the world are given due acknowledgment. But MoMA does not want to disuse the general formal and aesthetic values that have previously guided exhibition cultures in the institution. Fair enough. The next burden, it seems, now falls back on to the scholars and historians working outside the museum world, to provincialize MoMA and the exhibitionary complex as the privileged zone of history writing, [11] and to continue unearthing the multiple social, environmental, technological and global issues that could be addressed through architecture but are still excluded from the gallery space. Perhaps the biggest distance we need to travel is away from the established and public history of architecture that is written and disseminated by museums and exhibitions.

Martino Stierli, Anoma Pieris, Sean Anderson eds. The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947-1985 (2022) is published by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Copies of the book can be purchased here.

Esra Akcan is Professor in the History of Architecture and Urban Development and the Michael A. McCarthy Professor of Architectural Theory, and the Resident Director of Institute for Comparative Modernities at Cornell University.

Notes

- Thordis Arrhenius, Mari Lending, Wallis Miller, J.Michael McGowan (eds.) Exhibiting Architecture (Lars Muller Publishers, 2014) p. 15.

- See especially: “Brazil Builds” (1943), “Latin American Architecture since 1945” (1956), “The Architecture of Luis Barragan” (1976), “Mies Award for Latin American Architecture” (1998). The recent history exhibition “Latin America in Construction” (2015) often mentioned how it was building on MoMA’s own history of exhibitions on Latin America.

- Barry Bergdoll, “Out of Site/In Plain View: On the Origins and Actuality of the Architecture Exhibition,” E.L. Pelkonen (ed.) Exhibiting Architecture: A Paradox? (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015): 13-21.

- Martino Stierli, Anoma Pieris, Sean Anderson eds. The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947-1985 (MoMA, 2022) p. 15.

- Martino Stierli, Anoma Pieris, Sean Anderson eds. The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947-1985 (MoMA, 2022) p. 134.

- Martino Stierli, Anoma Pieris, Sean Anderson eds. The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947-1985 (MoMA, 2022) p. 134.

- Martino Stierli, Anoma Pieris, Sean Anderson eds. The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947-1985 (MoMA, 2022) p. 59.

- Martino Stierli, Anoma Pieris, Sean Anderson eds. The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947-1985 (MoMA, 2022) p. 161.

- Martino Stierli, Anoma Pieris, Sean Anderson eds. The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947-1985 (MoMA, 2022) p. 165.

- Gayatri C. Spivak, “Can the Subaltern Speak?”, Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, ed. C. Nelson, L. Grossberg (Urbana, Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1988) pp. 271- 313.

- I am taking the word “provincializing” from Dipesh Chakrabarty’s book Provincializing Europe, where he demonstrated that using Europe as a standard for concepts and values will produce a limited understanding of postcolonial times and spaces. Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. New Edition (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008).