Future Scenarios, Part I

Work on Paper

– Niall Hobhouse and Nicholas Olsberg

Capturing the rainbow: the city of tomorrow

On any given day late in the 1930s, so someone has calculated, more than 30,000 Americans either bought a train ticket or ordered lunch looking at one of the murals of the designer Winold Reiss.

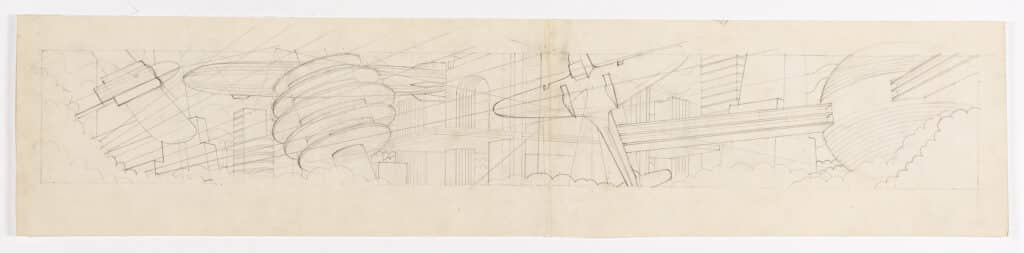

With each new commission, and as the burdens of the Depression slowly eased, Reiss’s graphics and wall scenes brought to ever more adventurous levels a vision of America’s architectural future that he had begun to imagine in 1931, in the section dedicated to labour at Cincinnati’s Union Terminal, a celebration in itself of the dynamics of the city of tomorrow.

By the time he drafted schemes for a new Longchamps café on New York’s Broadway — just below the new towers of Radio City, Reiss’s Future Cities were laced with radiowaves, shaped in fragments of planetary geometries, and pierced with sky-high roadways.

They reached a startling climax in a collaborative diorama — Capturing the Rainbow — at New York’s 1939 World’s Fair, whose foreground showed an entire people casting aside the tools of farm and factory to gaze upon the gleaming towers of a future city — post industrial, post agricultural, and brought to life without toil by two celestial spirits dropping stardust to the ground.

From Solomon’s Temple and the Tower of Babel to the legends of Atlantis, Oz and Eldorado, we have tended to imagine our futures, our lost histories and our half-known pasts as great architectural constructions and cityscapes. And because they are based in and out of time, like Babel and Atlantis and the Temple, every such reverie of construction seems to carry with it (and with almost as much delight) the image of its own destruction.

One wonders if the reason for dreaming our past and futures in terms of architecture lies in part because real, living cities are from a distance never entirely palpable. They hide the habited mundane behind the fancied spectacle of nothing but those “towers, domes, theatres and temples” that clouded Wordsworth’s eye one dawn upon Waterloo Bridge; beneath the chimerical light surfaces of Monet’s Thames Embankment; or in the dazzling “brightness and glory” that — so said the Wizard of Oz — compelled visitors to wear coloured glasses to survive entry to the Emerald City.

Hence it is always the architecture of the city in which our dreams of lost and future worlds are dressed, because the space remains narrow between a deep Atlantis and Constable’s London seen from Hampstead Heath or between Paul Strand’s 1921 film Manhatta viewed from New York Harbour and a vision of Eldorado. Once a city is in mind the eye does not have to work too hard to foresee the unseen or recollect the forgotten.

As much as can be imagined: The future as stage set

If Reiss dreams up a collage of things that almost might be, George Elliot, emperor of the world and denizen of a north country asylum, sees in one “division” of his vast palace of god a concatenation of temples that he believes are what the divine realm must be, and sees great human theatre surrounding it.

The great Enlightenment architect Louis-Gustave Taraval, in an actual theatre set (for the college that educated Molière), lets the stage, with its forced perspective, house a public square or courtyard at an uninterrupted scale grander than any city or palace could ever be.

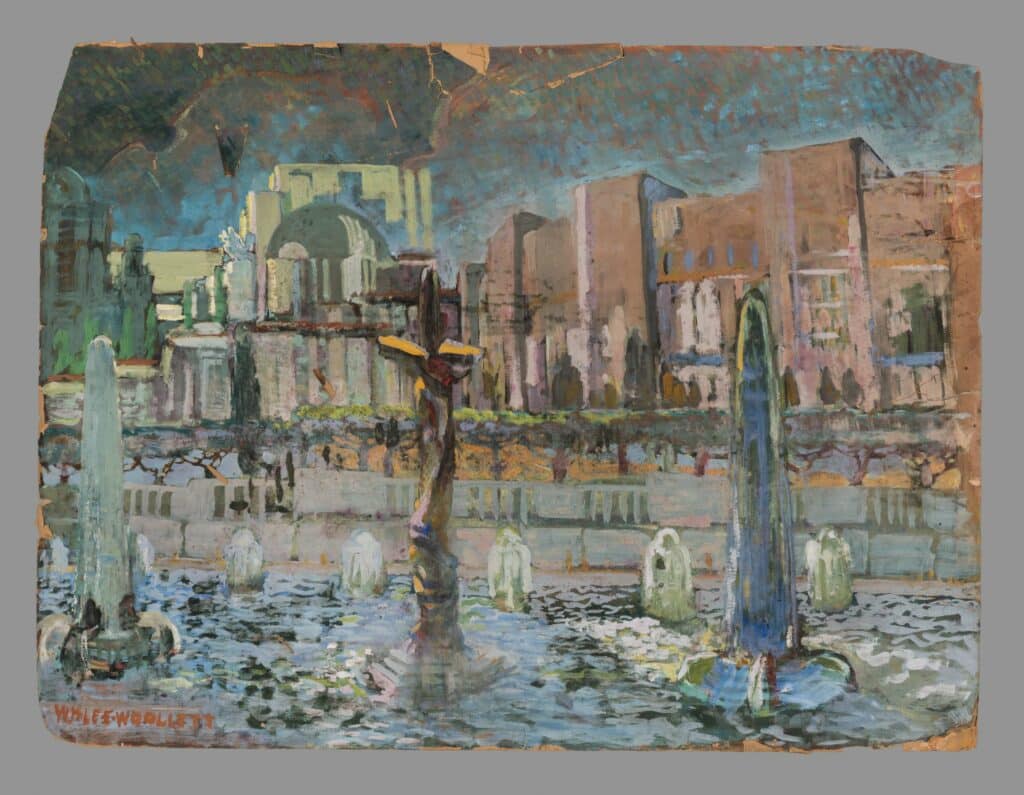

William Woollett, submitting to one among the half century of failed and impossibly visionary competitions to reimagine downtown Los Angeles as a coherent mass, organises his new city centre around an ornamental lake with lights, fountains, and a monument representing the “birth of flight”.

This is Woollett’s foreground for a massy citadel that seems at first to be a very vague evocation of archaic temples, newly dressed in the electric palette of neon and Technicolor.

In fact, it draws on a stage set too — the towering wood and plaster reliefs which had furnished a vision of Babylon for DW Griffith’s Intolerance. A shallow layer of sculpted facades hung on a vast web of scaffolding, the ancient city had been left standing for years at one of the main intersections of Hollywood, simply because the cost of disassembly surpassed Griffith’s means.

Until 1921, this had been the largest and most conspicuous architectural landmark in the city. So his proposal for a new city lies in an imaginative terrain between the region’s near future, which lay in its aircraft industry; its capacity to furnish power and water; and the persistent claim of Hollywood’s detractors and enthusiasts alike to have recaptured the manners of a Babylonian hedonism.

– Daniel Innes