Future Scenarios, Part III

Work on Paper

– Niall Hobhouse and Nicholas Olsberg

As much as is needed: Employing the lightest means

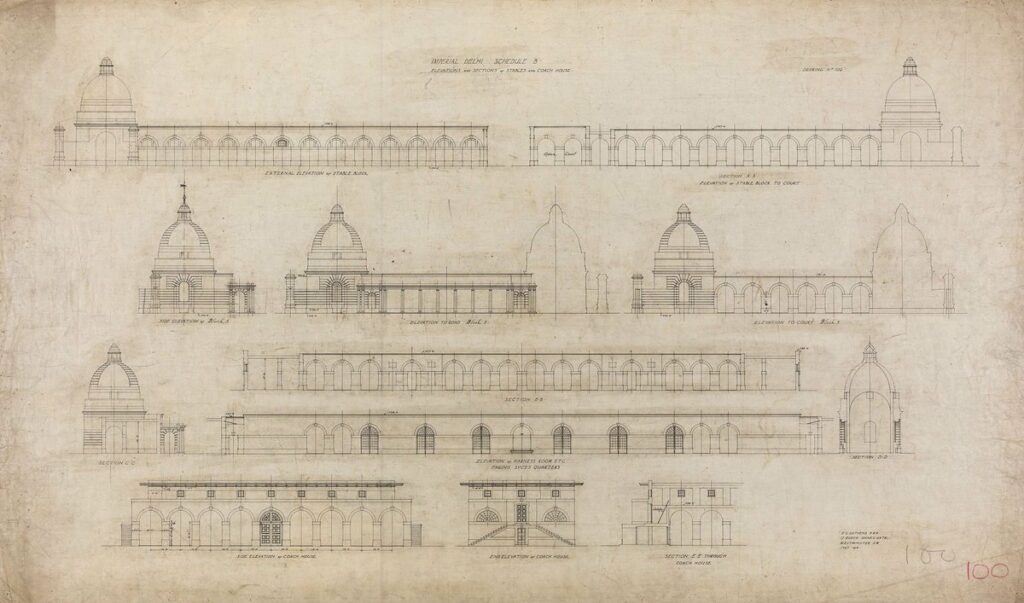

Few came closer to actually realising the grandest of grand designs imagined than Edwin Lutyens, called upon to realise something close to George Elliot’s Imperial Palace of God in New Delhi, or to avoiding its absorption and demise in the ensuing mix.

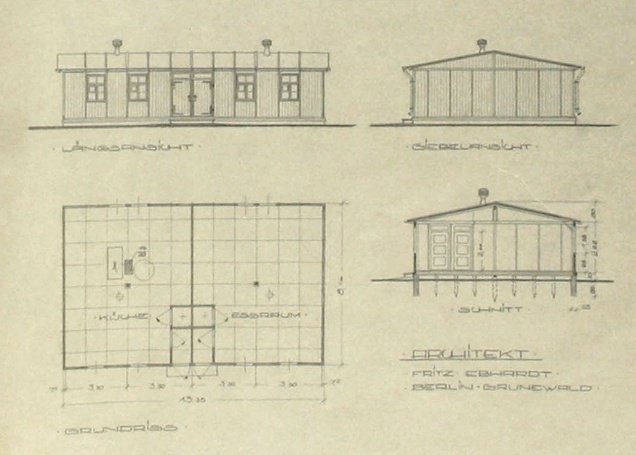

But as Lutyens’ drawings for the everyday quarters and services behind the monumental parade of George V’s vice-regal capital show, perhaps the best chance of realising and preserving a vast coherent scheme comes in doing as little as is needed, rather than as much as might be desired, and often — as Rossi also pleaded, and as Fritz Ebhardt’s housing for a military clothing plant make clear — in applying to them a familiar, even archetypal language, like that of a harbour warehouse, that can bear extended repetition and be varied to scale and use.

One gets a clearer vision backward to another day’s sense of the future from the ‘Googies’ and ‘atomic’ suburbs of Los Angeles, in which today’s useful mundane was cast in the sheen of tomorrow, than in the ever-straining conscious futurism of Disney’s Tomorrowland or the pointless Theme Building at LAX.

Hence to the less, to the least, and to the fancies that might be made of nothing. Here, in contrast to the splendour of Taraval’s theatrical city, in which actors had nothing but the dissolving perspective of a backdrop against which to act, is Duilio Cambellotti’s stage for classical dramas: a set of sculpted levels signifying at once very nearly nothing and something intensely emotional, as the shapes of the voids seem to talk already of the cries of grief and chants of resignation that bodies will mime and mouth upon them.

Thirty years later in Brussels Le Corbusier would build a pavilion out of coloured light and sound — a poème électronique whose architectural enclosure was dismissively assigned to his composer-assistant Iannis Xenakis — the real form being in the intangibles projected within.

It was Xenakis who worked with him on the acoustics of the Chandigarh assembly, for which drawings show architects working not with visual shapes which are rendered almost invisibly, but, like the Cistercian monks, with how to construct space for sound waves within them.

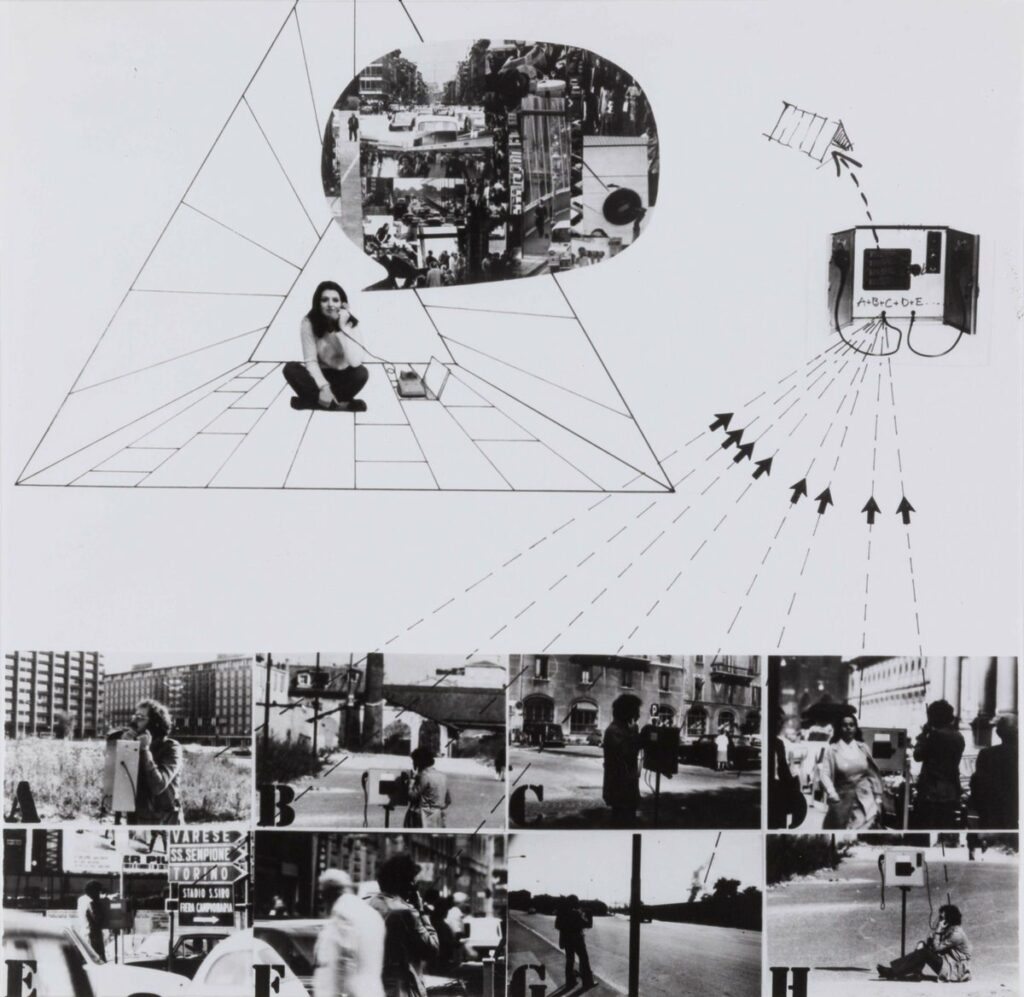

The Italian avant-gardist Ugo La Pietra went further, looking toward a future city in which the electronic poem was actually enough. A tiny fixed shelter for one human and a telephone would be a traveller’s vademecum, calling in all the social and built forces of the world that might (or might not) still be around it.

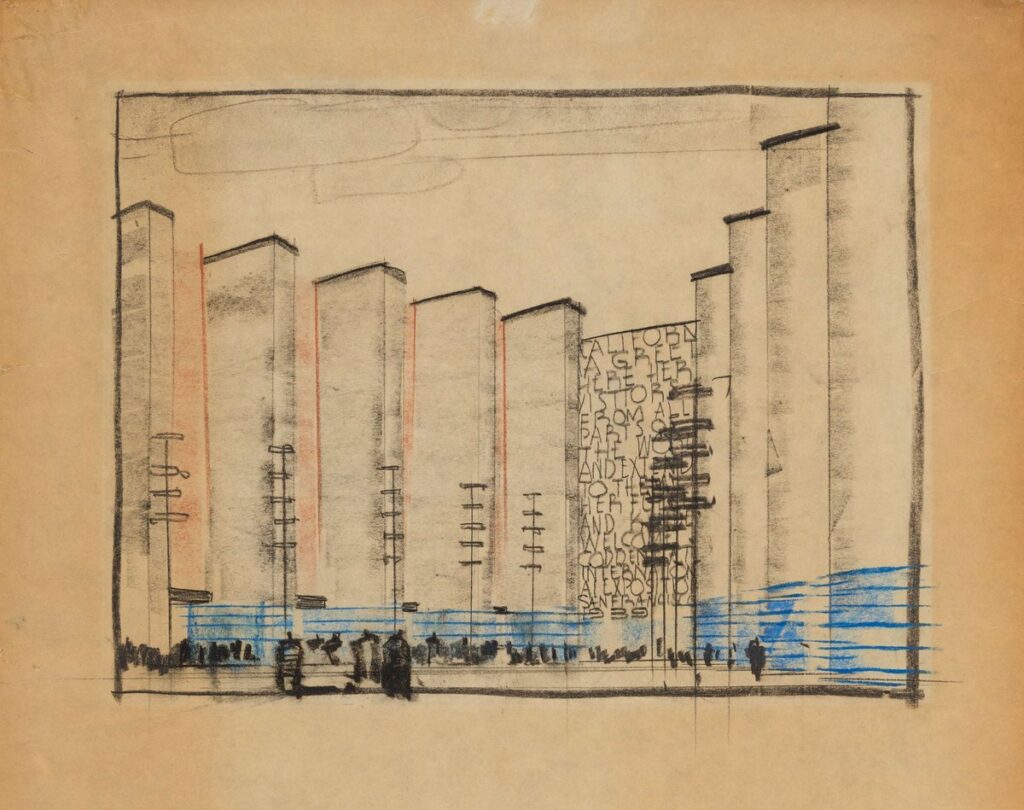

Ernest Born, designing a grand entry for the Golden Gate Fair in San Francisco, chooses simply to erect scrims to baffle the winds from the ocean and to use these airs as a welcome.

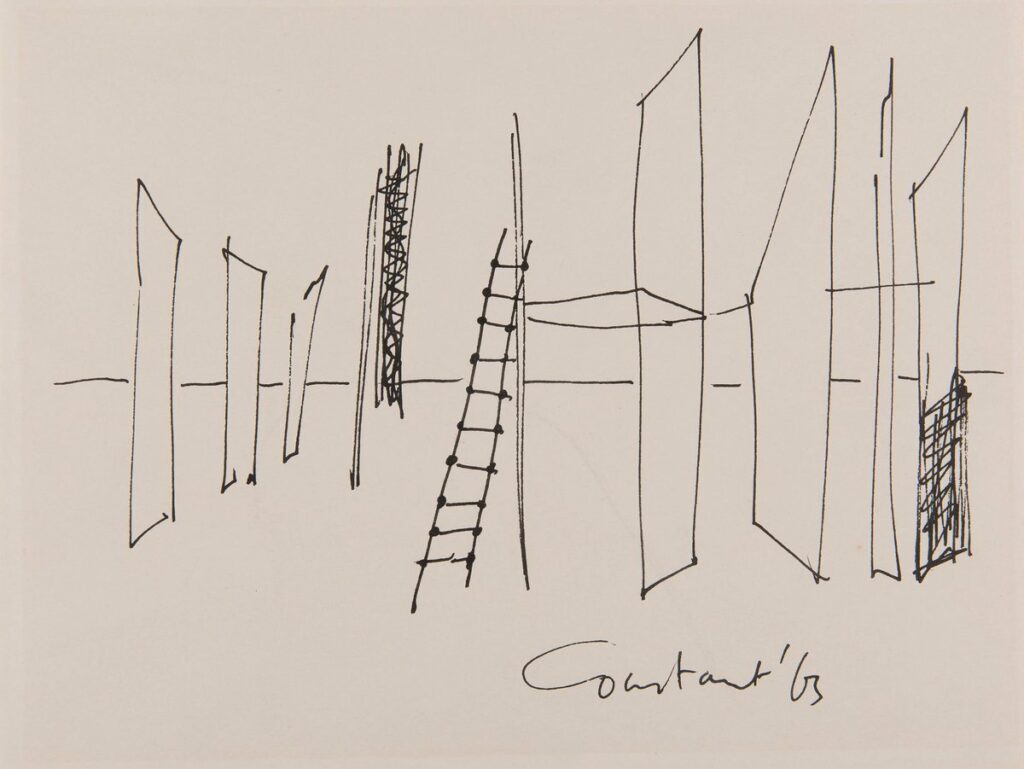

The situationist artist/architect Constant, in returning to a “New Babylon”, does something very similar in imagining an urbanism of the future composed mostly of Brechtian banners, just as Cedric Price’s response to a competition for the West Side railyards in New York was to erect wind machines in a void, bringing the spacious drama of elemental forces into a crowded, unbreathable and ‘delirious’ city.

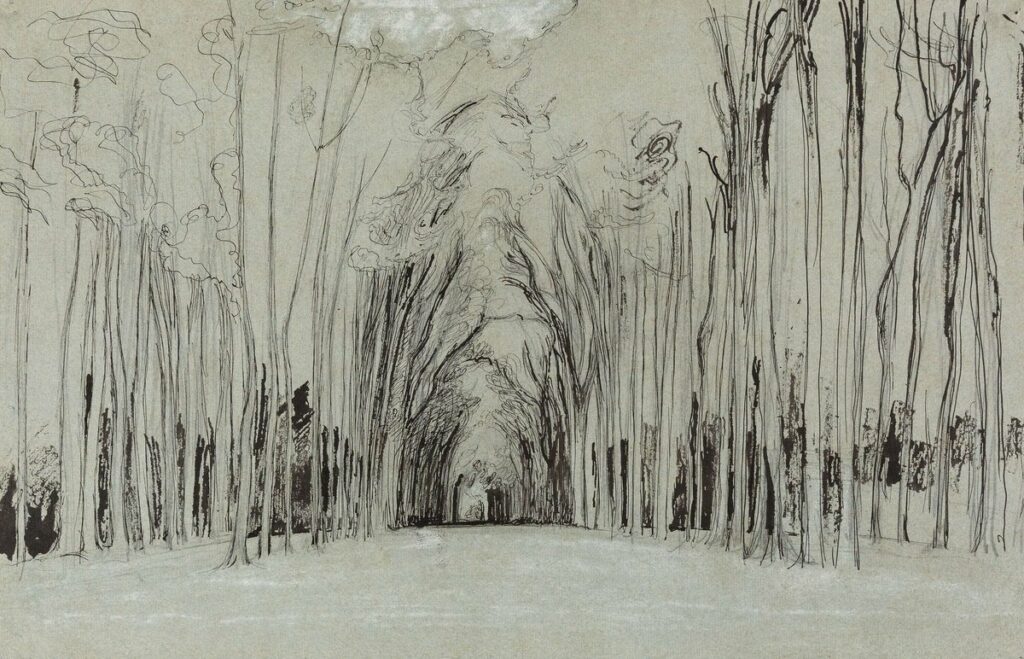

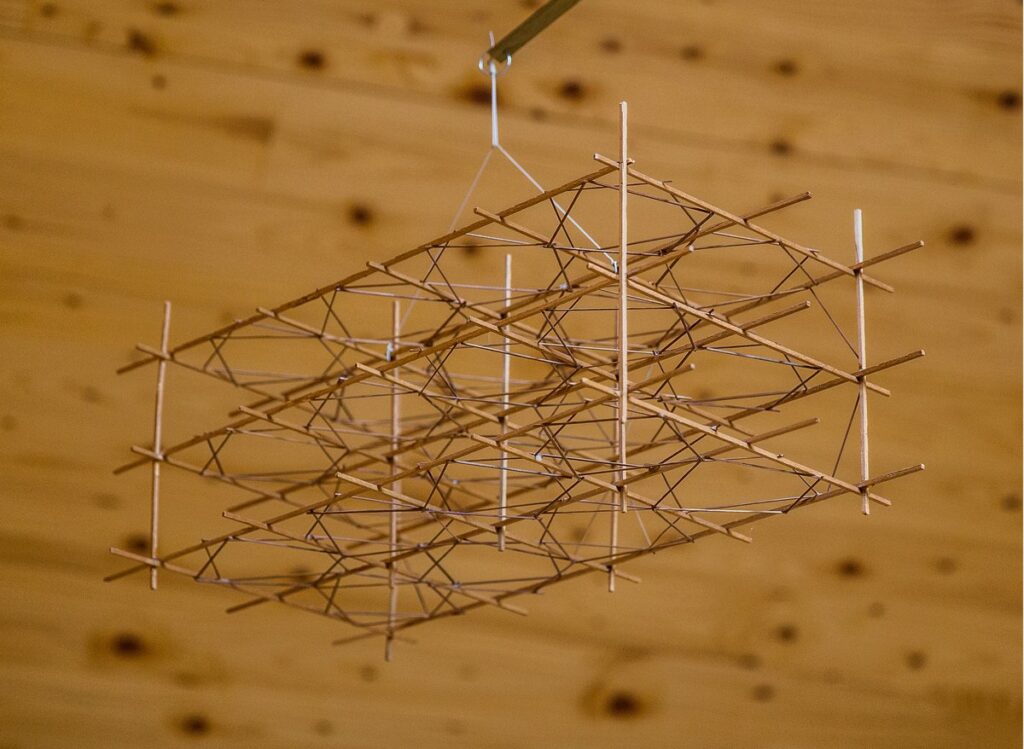

It is in the same spirit that Yona Friedman visualised his future cities not as masonry shapes in a new landscape but simply as a second tier of framework hovering above the old one. But none have yet gone so far in praise of the void as the art nouveau artist Charles-Marie Dulac, who saw for his hymn to creation all he needed of architecture in the vaulted space beneath a forest’s trees.

– Niall Hobhouse and Nicholas Olsberg