The Changing Metropolis 1940s–1980s

Work on Paper

– Niall Hobhouse and Nicholas Olsberg

Part III: Monumentalism and motion 1940s –1980s

A night rendering, making cinematic use of the dynamics of movement to suggest modernity, appears in the émigré architect Vassilieve’s ideal Manhattan, his animated drawing technique demonstrating how the varied shelves and openings of a setback megablock scheme bring energy and momentum, light and shadow to what could otherwise be a blank landscape of towering walls.

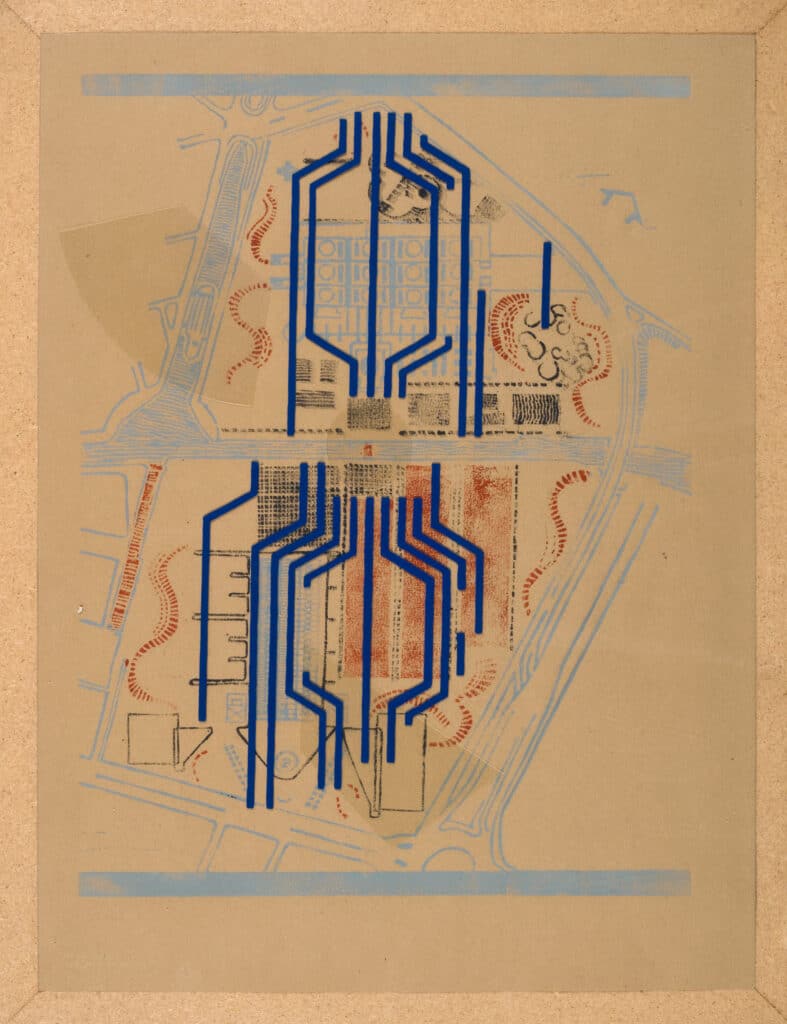

In the city of Rho, adjacent to Milan, Olivetti planned a massive research and calculation centre, with a community of 4,000 employees in tower blocks operating the huge labour-intensive calculating machines of the day, and with a cluster of social facilities, laboratory and research units, the elements that Le Corbusier explores in this study.

The project illustrates how the proliferation of exurban office parks and new towns raised the possibility of imagining a break with the grid, colour palette, and other traditional urban patterns, in favour of a near-random disposition of near-sculptural ensembles.

Sculptural topographies

At the same time, La Pietra — perhaps drawing on the “emotional architecture” theories of Mathias Goeritz — envisions such new urban perimeters and centres as skylines or topographies in which real sculptural monuments (like Constantin Brancusi’s Endless Column) might be interwoven to lend the city psychic force.

Natalini’s first thoughts on the universal idea that became Superstudio’s Continuous Monument seem to derive from a study relocating Florence following the floods of 1966 into a continuous urban form, linked to a web of autostrade and developed in a form close to that of a historical fortification system or the Great Wall of China (on which it drew). An early sketch showing the new “wall” in lovely sympathy with the folds of the Tuscan hills makes clear the serious topographic purpose behind what is often seen as a merely ironic proposition.

As the three adventurous propositions of Corbusier, La Pietra and Superstudio suggest, the development of meta-urban perimeters and satellites typified the expansive years of the 1960s. From 1973 onwards, reconstruction and expansion has more often focused on rehabilitation and adaptation of historical sites to accommodate new or wider use.

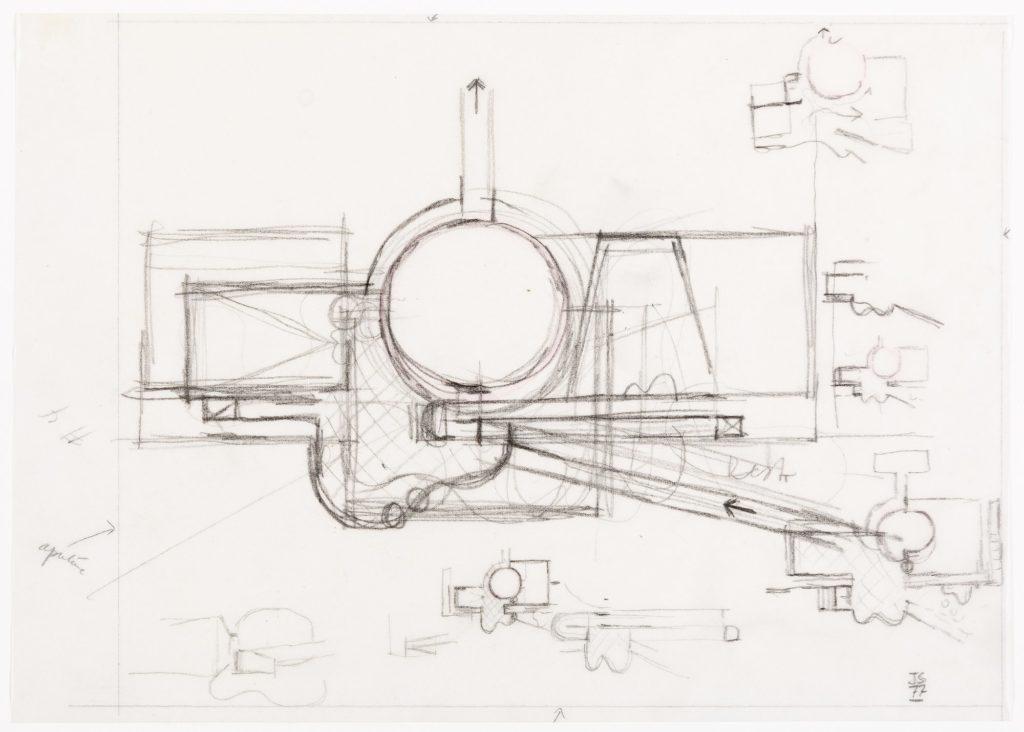

Here, too, the idea of breaking the grid, palette and pattern into which the intervention is made by inventing a collage or ensemble to accommodate old and new has been a forceful strategy — marvellously illustrated by James Stirling’s studies for the expansion of the neoclassical Stuttgart museum. As his sketches show, Stirling’s Staatsgalerie recognises that paths and motion are the essential elements of an art museum.

Price’s promenades

With his proposal for the Parc de la Villette competition in Paris, Cedric Price acknowledged the same pre-eminence of movement in the public park and plaza, generously tracing a wide choice of promenades along the Napoleonic waterways that had originally created this dockside warehouse district and the Second Empire conduits that had brought cattle to the city abattoirs and meat out to market for a hundred years.

And there, with Price’s walkable memory of inland docklands and public markets, and the echoes of Marcel Carné films that they evoke, we have brought the metropolis full circle.