José Oubrerie, In Memoriam

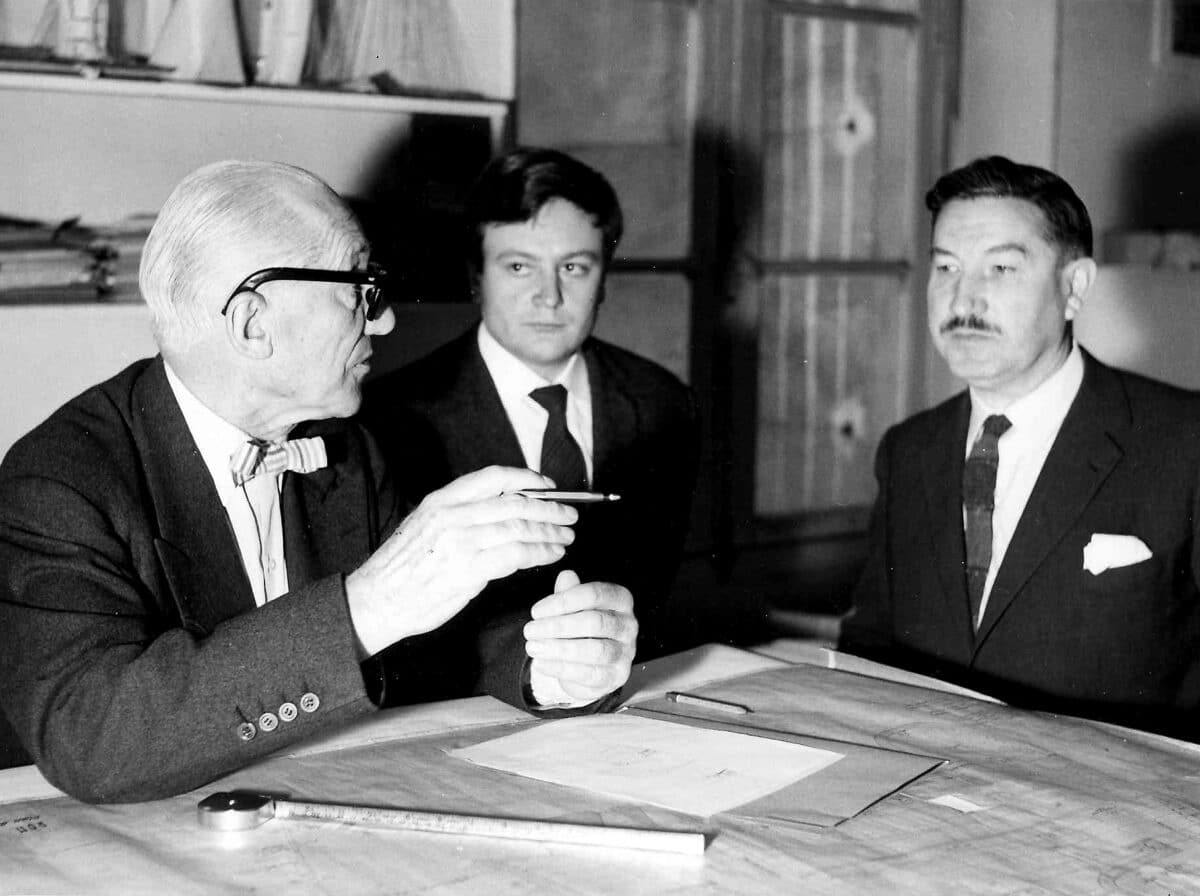

Very few contemporary buildings take nearly 50 years to be finished. Just this fact tells us a lot about the intensity, resilience, passion and patience of José Oubrerie, who passed away on March 10th, at 91. Aged only 27 when joining the atelier Le Corbusier in 1959, the church of Firminy became a key project that would mark his entire career, to be completed on the year of his 75th anniversary. Considered to be the last living witness of a bygone era, I would dare to say these early years of his professional life were as much of a gift as a burdensome responsibility.

In 2021, Drawing Matter had the opportunity to publish a certain number of articles signed by José, regarding the drawings in the collection related to Le Corbusier. Notably, those coming from the personal archive of Guillermo Julian de la Fuente. Close friends, they shared those remarkable last years at 35 rue de Sèvres, embarking on their first solo office right after. Given the small number of people working between 1959 and 1965, the Atelier 35S was certainly more of a research laboratory than a conventional architectural office. In a letter addressed to the team on February 24th, 1960, Le Corbusier writes ‘I’m here to give you the guiding ideas for creating things. You are mature enough to take all useful initiatives within the ideas given to you by me or that you help to discover’, closing up with the following statement: ‘there are a few of you and we do not want to be organised here in the American way (a form of organisation which does not correspond to the objectives that I intend to achieve)’.[1] As José confirmed in an interview I conducted in 2014, Le Corbusier followed every project, not always making drawings, but mostly, making choices, orienting the design process, picking out something that needed to be preserved, or identifying a point where a valid solution could be fixed.[2]

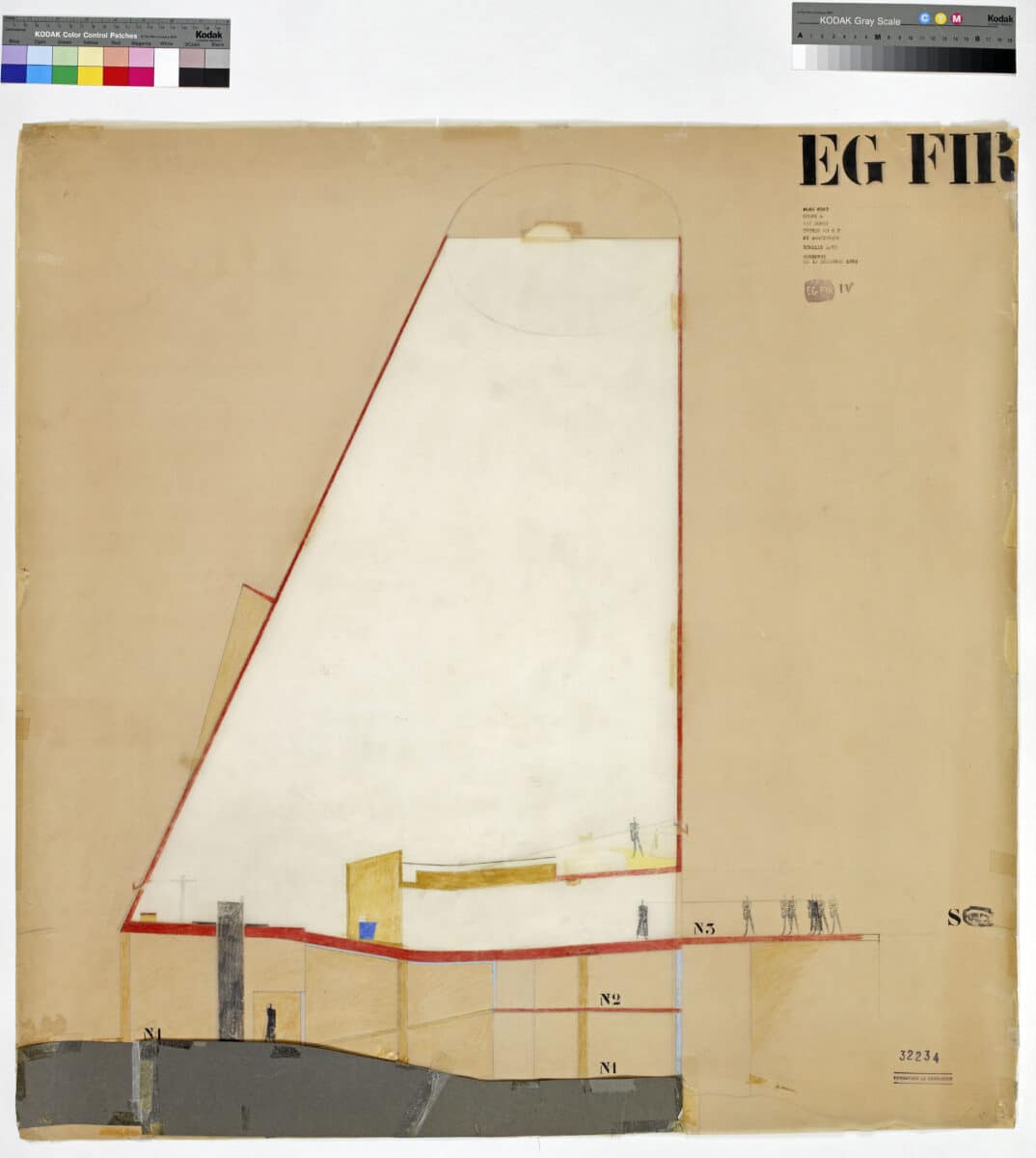

Models played a key role, but drawing was thoroughly used as an exchange, a prospective tool. While allowing a certain freedom, it allowed to synthesise heterogeneous constraints and give answers to manyfold challenges. Might it be a plan, a section or an elevation, these documents were all codified by a given set of colours and constructed with specific graphical devices that formed a kind of language. Circulation, materials, transparency, or installations would be given a presence on their own, making it possible for Le Corbusier to be extremely precise regarding his intentions while, at the same time, leaving space for interpretation. Deciphering these sets of instructions was done with other colleagues at the office, trying to remain as faithful as possible to the directions. A great example of this methodology was done by José himself in an article published here on June 15th, 2021, taking the drawings for the Governor’s Palace in Chandigarh as a base.[3] These documents were real living entities, subjected to all kinds of mental and material transformations. Superimposing, cutting, reframing, folding, erasing, or using scotch would eventually lead to a final solution, which would be then neatly fixed on ink. Even in the final drawings handed out to the client, some elements would remain extremely volatile in their definition, if the appropriate solution hadn’t been found. This can be typically seen in the cross sections of the Firminy Church, where the upper part of the cone does not have the same precision as the rest. The entrance volume, still missing to the right, clearly shows how far they were from achieving a satisfactory solution. In the process, a drawing could be left aside for some time, ‘cooking in the oven’ as they said, to be recovered later and reworked with a new refreshing approach.

The long corridor of the Atelier was like a melting pot, where drawings and models would move around from table to table. Strategies already implemented in the past would be literally ‘tested’ on the new projects, as a way to see how these latter would react. In this sense, the ‘clouds’ used in the Assembly building as acoustic elements depicted in another article appearing in Drawing Matter would be transferred to La Tourette, subsequently abandoned, proposed again for the Firminy church, to be finally discarded in favour of a grainy finishing.[4] When orienting his collaborators, Le Corbusier would always refer to the Complete Works. It was not meant to be read as a source of formal inspiration, where solutions could be copied and pasted, but much more as an example of how to deal with uncertainty through experimentation and trials. This was obviously a great learning for José, both during those years, but also when taking full responsibility for the Firminy Church, and even further, for his own projects. We must not forget the rough definition of the drawings when Le Corbusier died in the summer of 1965. After much effort, on-site work for the church started in 1970, to be fully stopped in 1976 due to financial problems. Either at that moment, or in 2003, when the final stage took place, the design of the church would have to face unexpected challenges, from structural issues regarding foundations to updated regulations impacting fire exits. Every time, José would apply the same approach in order not to alter the original intentions, interpreting the guidelines given by Le Corbusier.

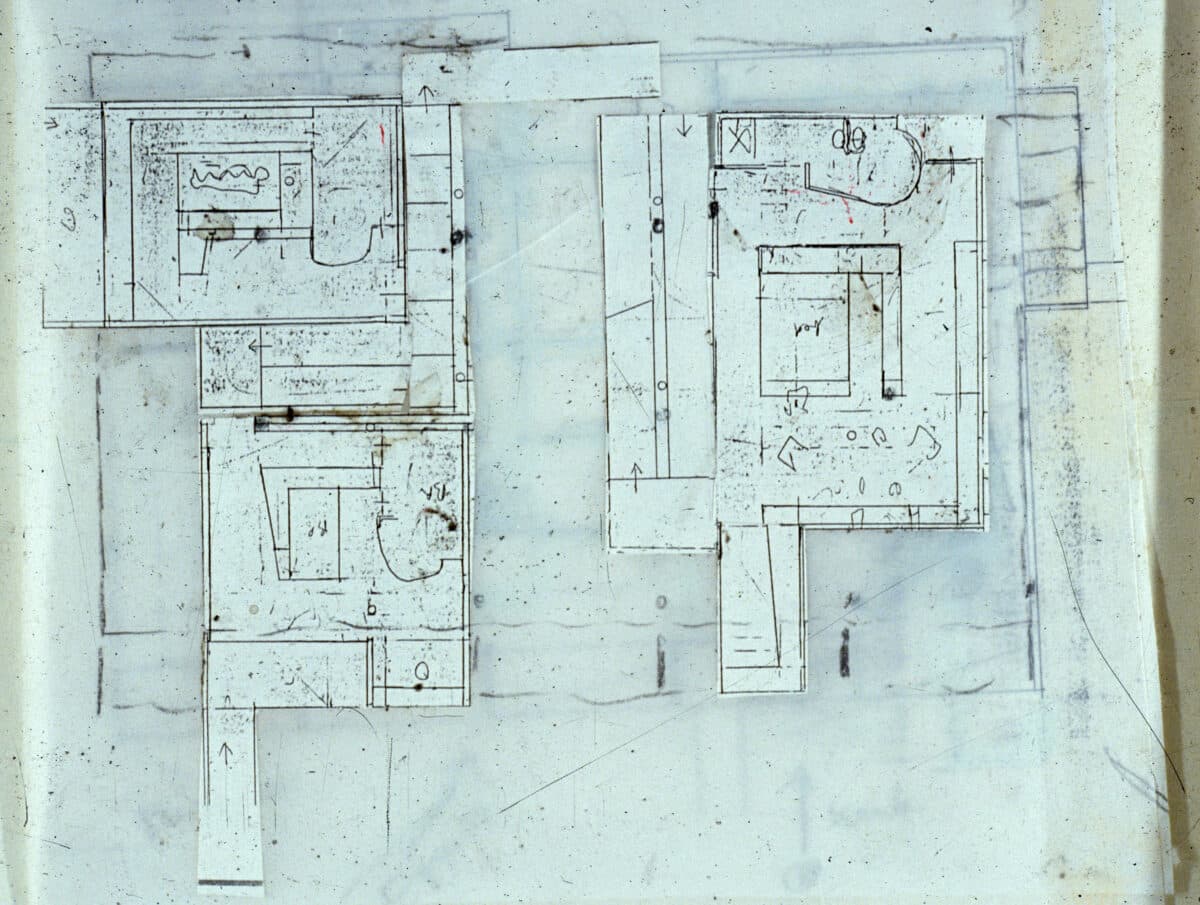

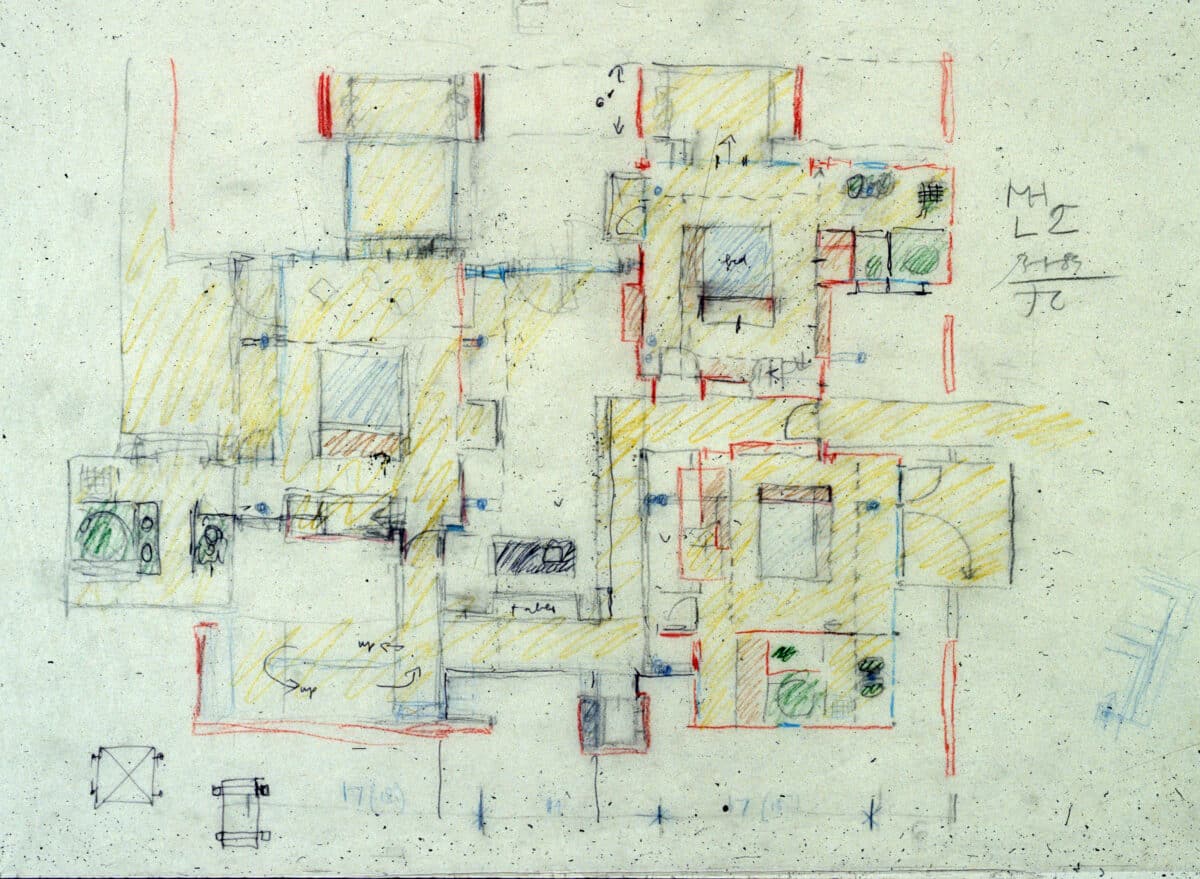

In between those two stages, he had the chance to conceive the Miller House, built in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1987. Taking Villa Shodhan as a reference, it was the time to fly on his own, using this commission in this ongoing dialogue with his mentor. Paper models, but also plans, reveal that the working methodology was still relevant. Each one of the apartments was conceived as an autonomous object, responding to precise constraints for each member of the family. Floating within a structural grid, elements borrowed from Le Corbusier’s universe would come into play, striving to sometimes link, sometimes separate these living units, articulating the presence or the absence of individual and collective rituals. Cut out on thin white paper, these cocoons could easily ‘navigate’ on the large surface of tracing paper, playing with different configurations, testing conditions where intimacy or openness was at shake. If the forms certainly belonged to Le Corbusier’s formal vocabulary, José learnt, more than anything else, a way to approach architecture, and by extension, the world in which we live. When reflecting on the Miller House, José wrote a short presentation text which can be considered a manifest for architecture. Now that he’s gone, these words will certainly give the measure of his own contribution:

‘To build, which is also to construct, is to dream your own existence, at the same moment that you live it. To build is to reiterate and protect, as you had to act rationally, the irrationality of your dream.’[5]

Notes

- Translation from the author : « Je suis là pour vous donner les idées directrices concernant la création des choses. Vous êtes assez grands pour prendre toutes les initiatives utiles à l’intérieur des idées qui vous sont donnés par moi ou que vous aidez à découvrir. Vous êtes quelques-uns et ne nous voulons être organisés ici à l’américaine (forme d’organisation qui ne correspond pas aux objectives que je me propose) ». Guillermo Jullian de la Fuente Collection, CCA Archives. Translated by the author.

- Luis Burriel Bielza, José Oubrerie, ‘José Oubrerie a dessiné les plans. Paris 21 mai 1964’, DEARQ – Revista de Arquitectura / Journal of Architecture, nº14 (July, 2014), 8–33.

- José Oubrerie, Notes on Twelve Drawings for the Governor’s Palace at Chandigarh, 15 June 2021, <https://drawingmatter.org/twelve-drawings-for-the-governors-palace-at-chandigarh/> [accessed 30 October 2024].

- José Oubrerie, Notes on the Palace of the Assembly and Museum at Chandigarh, 7 June 2021, <https://drawingmatter.org/the-assembly-and-museum-at-chandigarh/> [accessed 30 October 2024].

- José Oubrerie, Architecture with and without Le Corbusier: José Oubrerie Architecte (Philadelphia: Oscar Riera Ojeda publishers, 2013), 188.

Practicing architect, researcher and associate professor, Luis Burriel Bielza holds a PhD from the Polytechnic University of Madrid (ETSAM) with the title Saint-Pierre de Firminy: the building as an objet-è-réaction-émouvante. Bielza is currently a researcher at the IPRAUS Research Laboratory, at the École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Paris-Belleville, where he also teaches design studio.

– Paul Clarke