Missing Link: Strategies of a Viennese Architecture Group (1970-1980) – Review

There is a strange moment in the second room of the exhibition, where all kinds of great works are hung on the walls to admire, organised around a central display of plastic and aluminium furniture: a collage of a car hovering like the golden calf amidst a crazed crowd; a photo of a group of three men wearing transparent plastic helmets; various record covers; an edition of Casabella with a Gorilla on it. The problem is, that although this is an exhibition about the Viennese architecture group Missing Link, none of the eye-catching work was made by them. The furniture was designed by Hans Hollein and Walter Pichler, the car collage was made by the group Zünd-Up, the three men wearing the futurist helmets are the members of Haus-Rucker-Co (Laurids Ortner, Günter Zamp Kelp, Klaus Pinter), the record covers feature Simon and Garfunkel, the Rolling Stones and others, and the Casabella cover is by Casabella. It’s not like there is nothing made by Missing Link here, but their work appears marginal. Inadvertently, one starts to wonder what would be missing if it had not been for Missing Link.

Indeed, Missing Link have largely been missing from the general account of the wild-and-crazy Viennese architecture groups which came out of 1968 counterculture and stretched the very meaning of architecture and an architect’s job description. This general history used to centre on Coop Himmelb(l)au, maybe also taking Haus-Rucker-Co into account, but that was about it, at least from an international perspective. While the work of Zünd-Up has at least been acknowledged by a respectable publication in 2001 [1], Missing Link has so far not enjoyed such a presence in the general perception of 1960s and 1970s architecture. Founded in 1970, and thus the last to be established of the four Viennese activist architecture groups mentioned here, it seems that they almost came a bit too late, even though the formation of Coop Himmelb(l)au predates them only by two years. But history and publicity can be harsh when it comes to chronology, and often history is read backwards: The early work of Coop Himmelb(l)au seems interesting not least because of its later architectural success, when the office built buildings and banned its “I” between brackets [2].

Missing Link never built anything which could be called architecture in a conventional sense. As a group it is, or rather was, composed of Angela Hareiter, Otto Kapfinger, and Adolf Krischanitz, who as with the other groups that came to be known as part of the “Austrian Phenomenon” [3], met at the Technische Hochschule, today Technische Universität, in Vienna. Then, as now, it was the prime place in Austria for architectural eduation, at least in size. “Missing Link” was the subtitle of one of the group’s designs and became paradigmatic, referring to the missing links between architecture, urbanism, everyday life, artistic and social engagement. The 2022 show at the MAK, Vienna’s Museum of Applied Arts, was made possible and inspired by the fact that in 2014 the institution purchased a large collection of the group’s work and has since acquired more through donations. Thus, the exhibition is an outcome of the enormous accomplishment of sorting, cataloguing and structuring this comprehensive archive of the group.

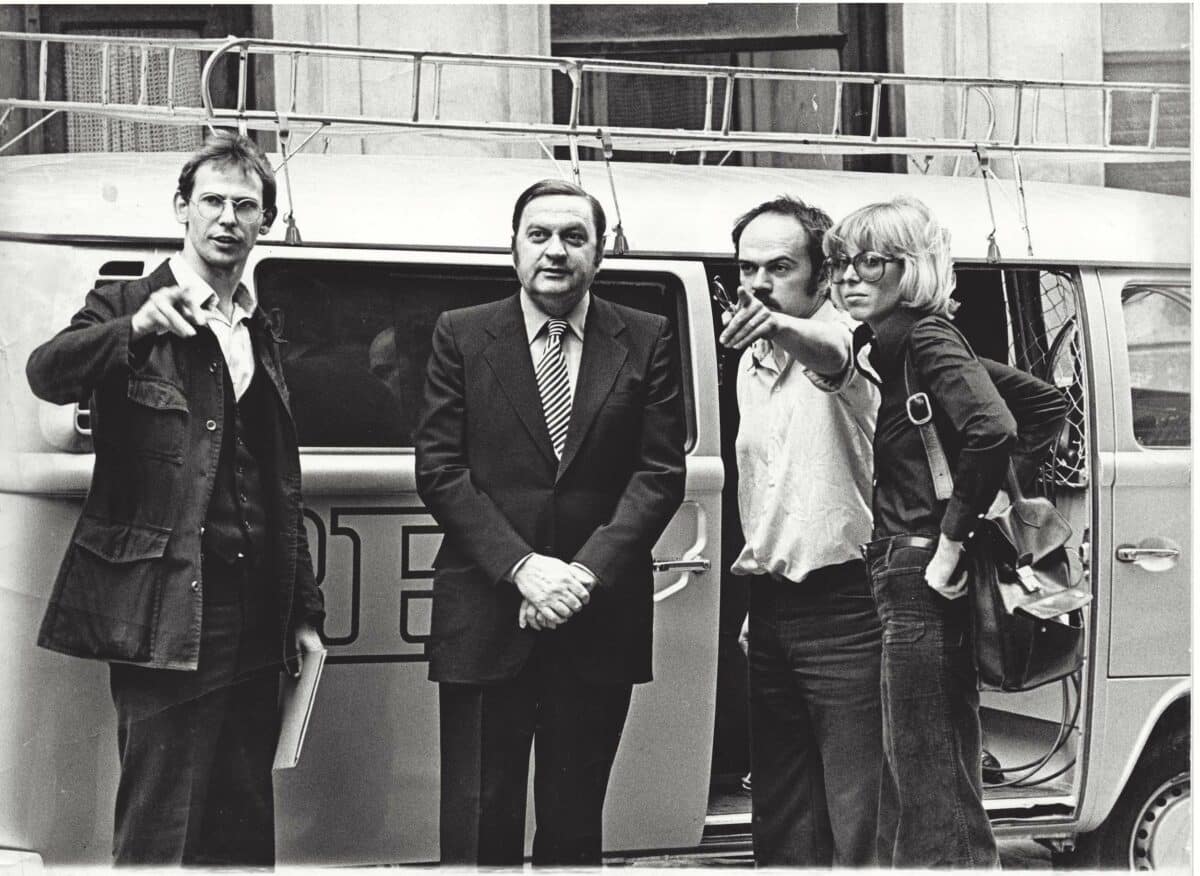

This prominent show at one of Austria’s grand cultural institutions makes up for the lack of attention the group has had so far, yet it happens at a moment when history writing is not about creating new heroes anymore. Not only does the exhibition underline the fact that Missing Link was the only group of Austrian young architects to have a female member, it also makes an extraordinary effort to locate and portray Missing Link in context. This explains why, in the second room of the chronologically structured exhibition, the group’s work almost disappears, or least melts into what was happening simultaneously in Austrian architectural, design, artistic and pop cultures. This perspective is, of course, intentional; it is characteristic of the exhibition’s viewpoint, and it is true to a time when architecture was not about individual, big names but about collaboration. This is highlighted in the rich accompanying catalogue by an impressive and deeply researched essay entitled “Missing Link in Context”. This small opus magnum by curator Sebastian Hackenschmidt stretches over some 150 lavishly illustrated pages.

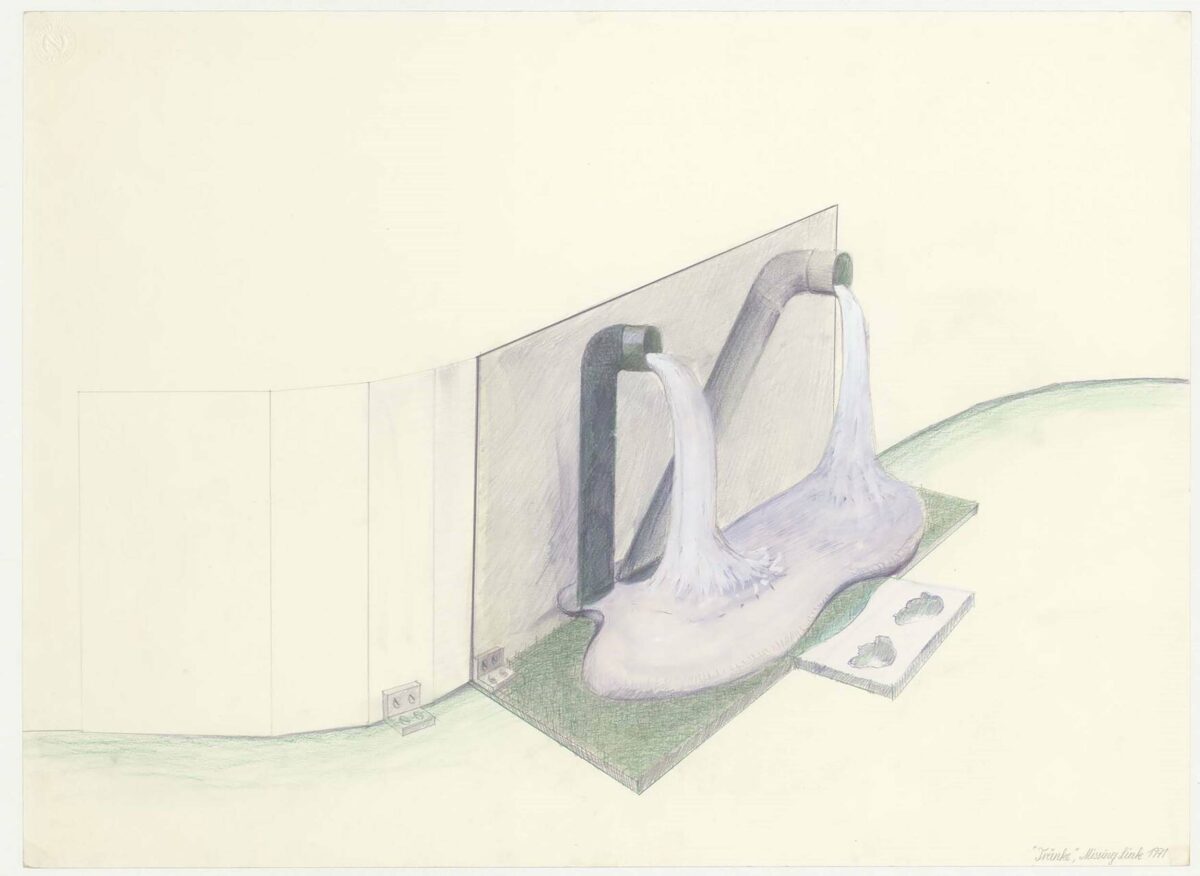

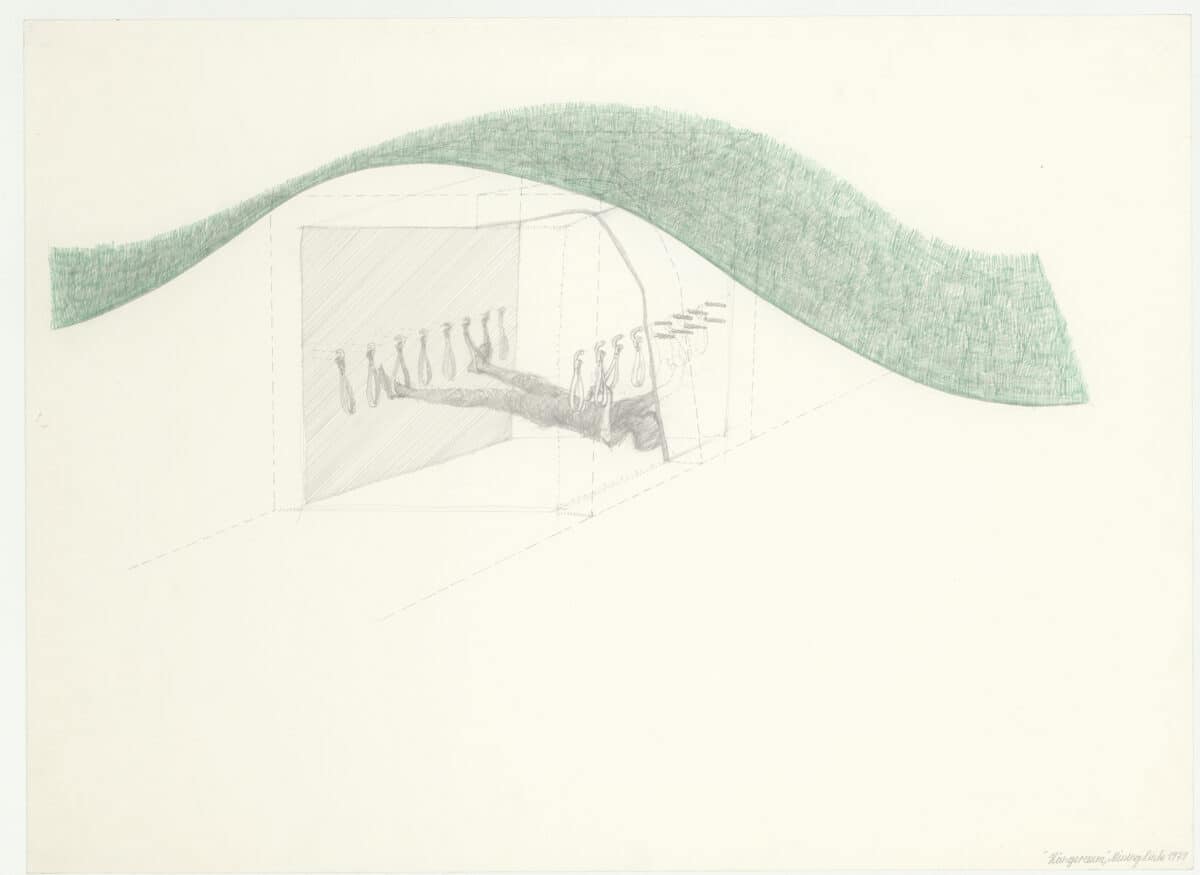

This is not to say, however, that it was the curators‘ intention to drown the group in the cultural streams of the 1970s. Beyond room 2, there are rooms 3 et seq., and it is here where the emancipation of Missing Link from their only slightly older forebears becomes more pronounced. As opposed to the often technoid late 1960s inventions (between the space age and an earth considered only a part of the cosmos and requiring architectural survival kits) Missing Link started into a more earthy direction, influenced by what one might today term an ecological aesthetic, if not worry. Several watercolour paintings showing the group’s “Fleder-housing” furniture represent an unexpectedly low-tech, traditional technique. Equivalent designs very evidently refer to the pun in their name – Fledermaus is the German word for bat: the objects unfold, spanned between fragile members in colours and a suggested texture characterized by the hues of the spookiness associated with this creature.

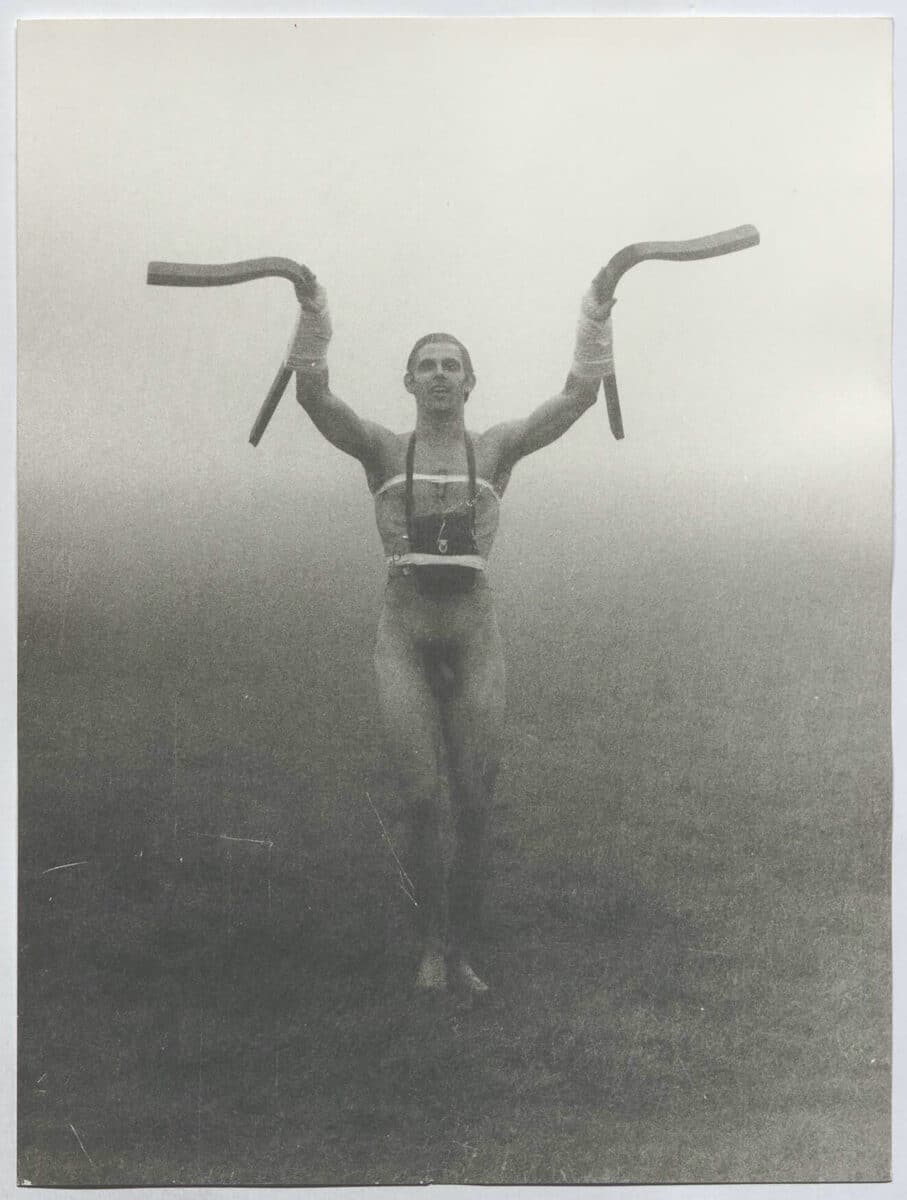

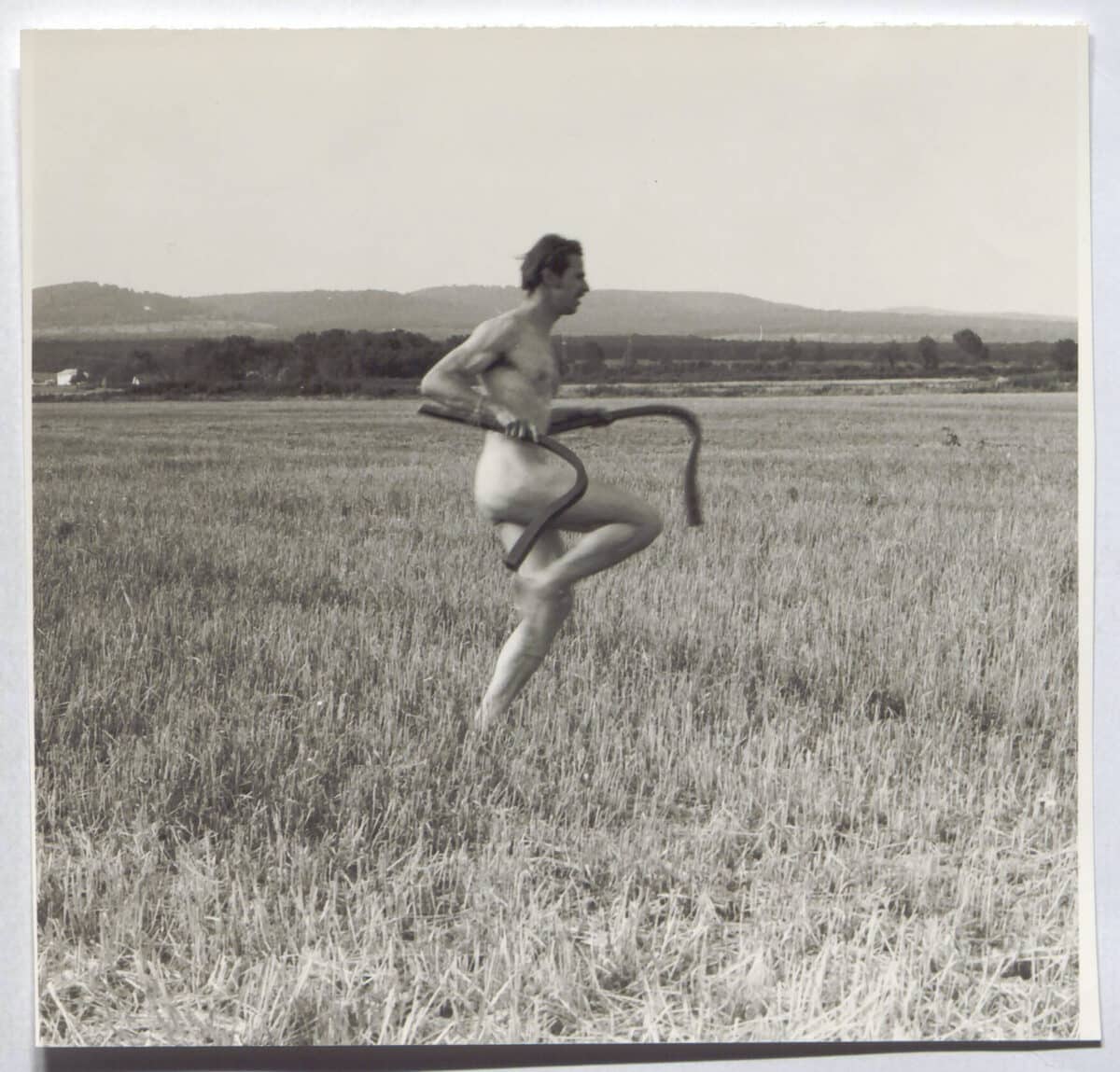

This tendency developed into increasingly surrealist aesthetics, which qualify the mid-1970s projects and activities of the group. One of the most fascinating exhibition pieces is a sequence from a film that Missing Link made in cooperation with the ORF (Austrian public television) featuring human beings swimming or jogging through a somewhat apocalyptic rural landscape equipped with wooden and plastic objects, which could be interpreted as protective gear, or perhaps as devices that echo human movement in a bony structure which by their repetition and staccato rhythm reveal the potentially totalitarian character of human mass movement. This is complemented by surrealist, yet visionary rather than retrospective scenes, the most striking being a sterile meeting of three people around a coffee table, each stuck to their own newspaper holder without communication, immediately calling to mind today’s fixation to mobile phone screens. It is quite telling that this scene was filmed at Café Sperl, one of Vienna’s grand traditional coffee houses. There is a particular and increasing Viennese-ness infusing the group as time progresses. This is evident in a series of magnificently fabricated ink drawings featuring classic props of the Kaffeehaus, some of which have been partially transformed into seascapes – a round table becomes an ocean surface and an ashtray a lifeboat, as well as Thonet chairs and newspapers. It is fascinating to follow the group through its works into the late-1970s and thus from their activist beginnings towards the dawn of postmodern architecture. As a practising architect Krischanitz, particularly, would become an important local contributor to postmodern Vienna, while Kapfinger went on to become a well-known critic. Hareiter, having left the group in 1974, made a career as an art director in film and television. It is a great accomplishment of the MAK show to neatly portray and lay out the complex and anything but matter-of-course route from Viennese activism via the rediscovery of Vienna’s classic architecture and design to the sweetish shapes and colours of postmodernism. In that sense, a great success of the show is to make a link missing so far in the discussion of Austrian architecture, as many groups formed around 1970 took a similar path.

This breadth of positions goes along with an incredible wealth of material. The show is exceptionally large and verges on the overwhelming. Yet it is a pleasure, right up to the last object, because the exhibits fall into so many categories, from (a lot of) paper architecture in pencil to films, wooden and metal objects, slick lacquered furniture, to cardboard models. Sorting all this into art historical categories, with all sketches measured and neatly registered in their manifold techniques, also means that what was a movement in the 1970s has now become firmly historicised. As when closing the last pages of a captivating novel, one cannot but feel a bit melancholy leaving the exhibition.

Sebastian Hackenschmidt (with the MAK Furniture and Woodwork Collection) ‘Missing Link: Strategien einer Architekt*innengruppe aus Wien (1970-1980)’ is on display at Vienna, MAK Museum for Applied Arts, until 2 October 2022. The catalogue for the exhibition, edited by Lilli Hollein and Sebastian Hackenschmidt, can be purchased here.

Erik Wegerhoff is a lecturer at the Institute of History and Theory, ETH Zurich and editor at the Schweizerischen Bauzeitung – TEC21.

Notes

1. Martina Kandeler-Fritsch, Zünd-Up: ACME hot tar and level (Vienna: Springer, 2001).

2. Himmelblau in German means sky-blue; Bau means building.

3. A description coined by Peter Cook in 1970 and recently taken up by various exhibitions, also in Austria.

– Editors