Postcards: The Nature of images

Our vision is simultaneously determined by the (past) historical structure of the work and by the present structure of the gaze that examines it, in which the accumulated glimpses of history often continue to operate.

– Daniel Arasse

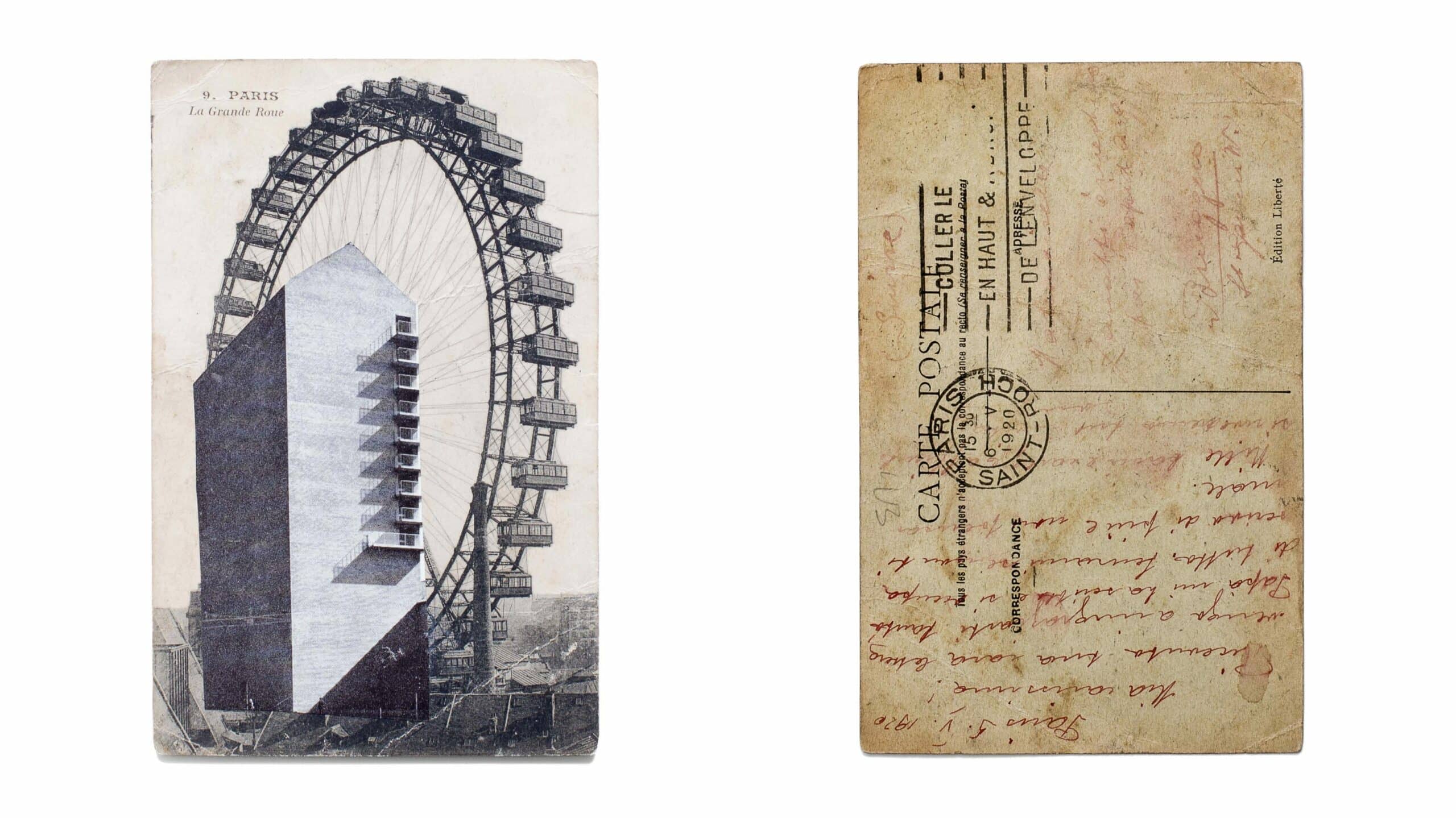

Writing a postcard is the simplest thing in the world. Among other things, it is a very contemporary form of communication: one works on a short text, and with images. Sending a postcard is also a way of trying to stop time or, rather, trying to create a relationship between different times.

I must confess I like accumulating different objects; I try, of course, to curb this attitude. Among these objects are books, postcards, photographs, but it is also difficult for me to separate myself from the fragments that narrate my travels and my interests, the places that fascinate me, my sensations. They are fragments that come from the places I have passed through.

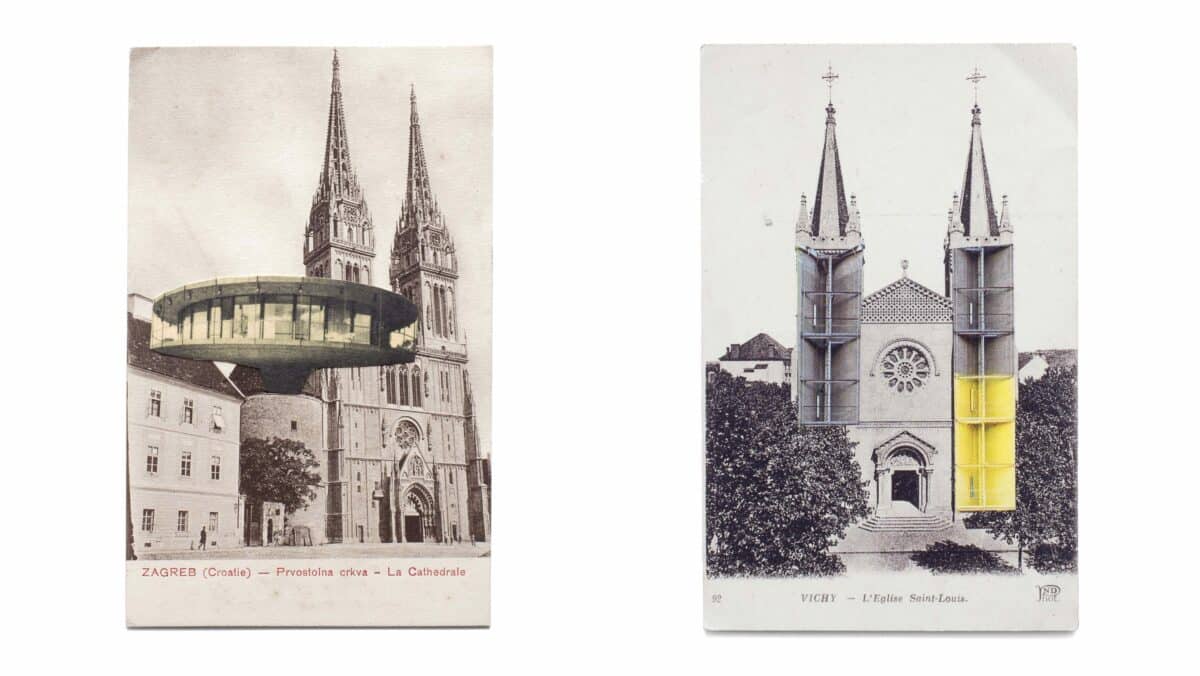

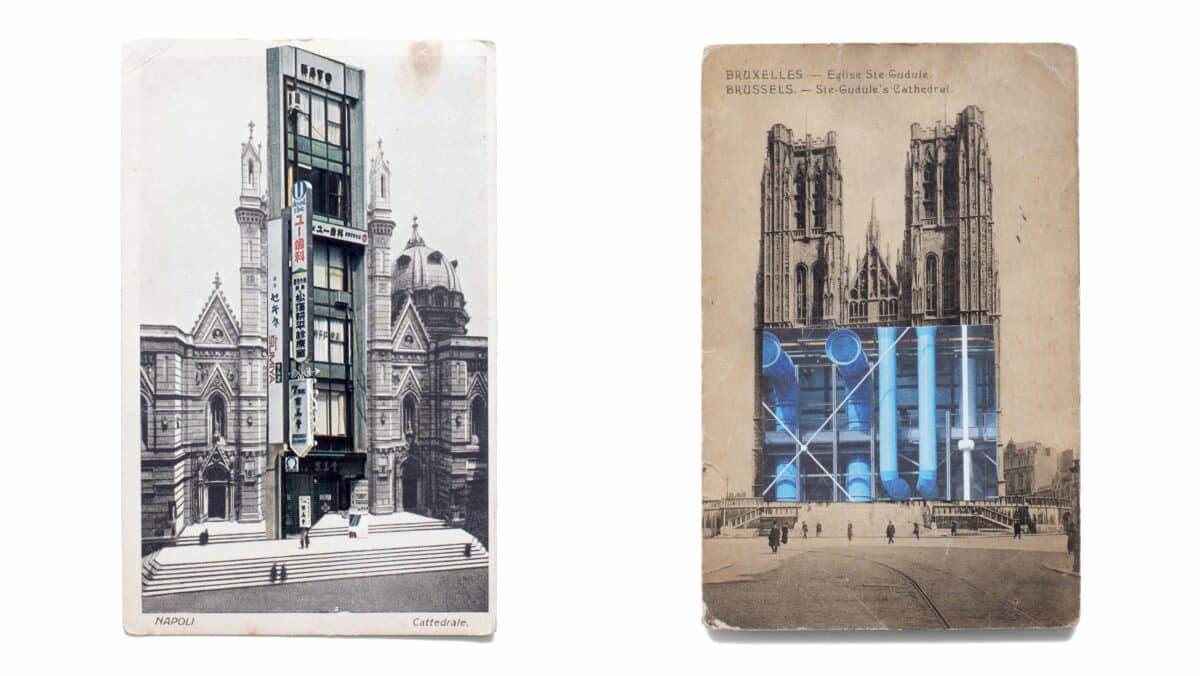

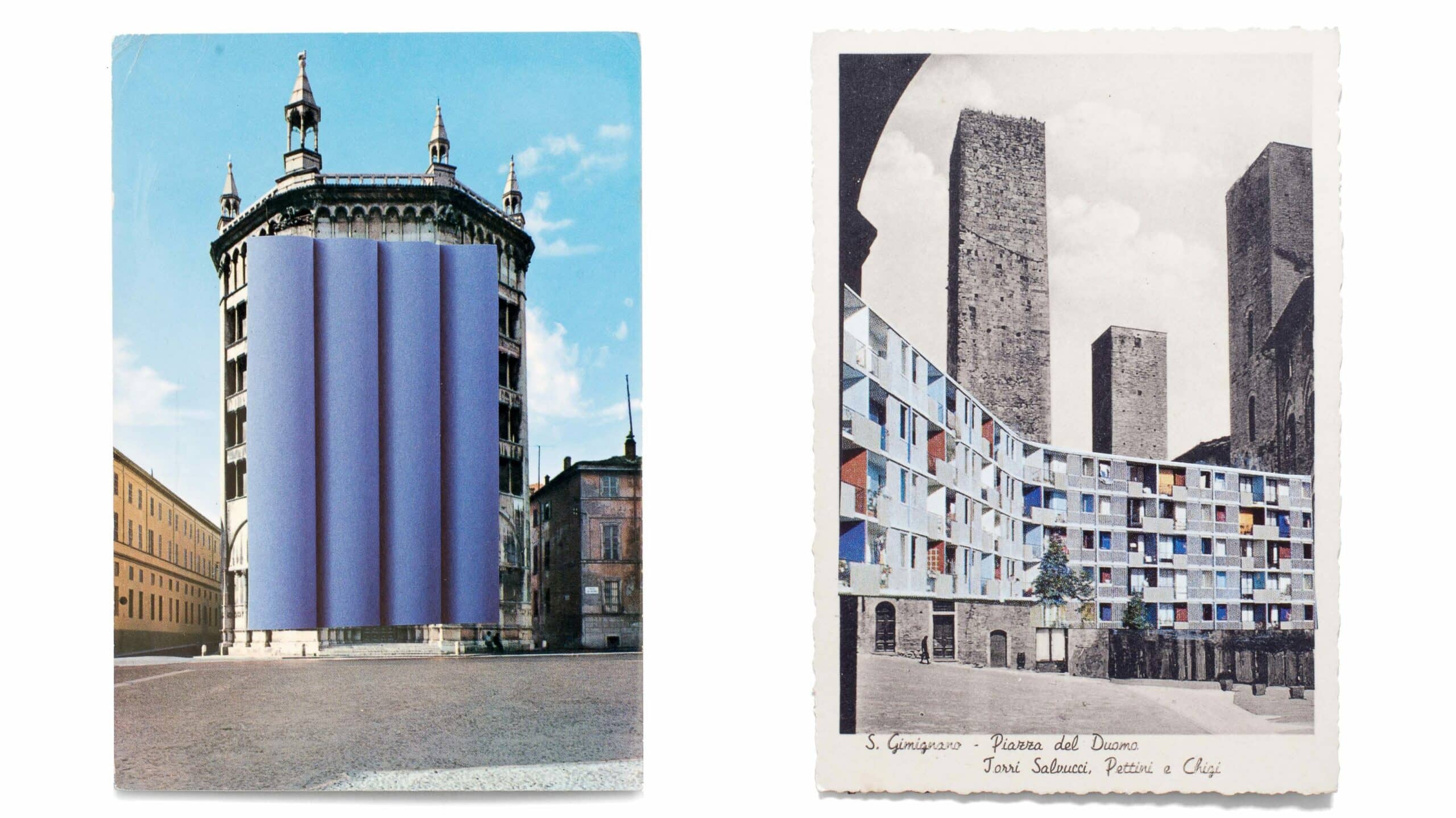

One day, I began to look at these images, and I tried to get in tune with them. I looked for something else in the framings, I saw different projects emerge, almost by chance.

At first I started to transform them: I wrote them for friends looking for words, but also trying to build the images on the back with fragments of photographs.

Mine was a form of ‘other’ writing, an attempt to impress in my memory certain signs that would evoke others, in an endless game. A journey through the territories of architecture.

I intervened on the ground of the image; I did not use words, but fragments of architecture that came into contact with the times of the image, producing new meanings, reflections and interpretations.

Rather than using montage in its digital form, I needed to compose it by hand, with what I found, to weave again the worn links between the world (which changes quickly) and memory.

In fact, the past interests me only if it lasts long, and if it can be combined with the present.

The postcard is simply ‘a print on a semi-rigid support for postal use for non-confidential correspondence.’ [1]

By making my personal public archive, I try to revitalise this object, giving new life to memory, but also to my present.

A postcard in the time of text messages and emails represents the revenge of concrete relationships. Just as manual operation is an attempt to respond with the slow time of montage to the proliferation of digital images. The montage for me is a form of drawing.

It is easy to buy a series of postcards on the internet, but it is more difficult to actually find them in street markets. I don’t for them on the web, it’s the images that find me every Sunday. Once found, the images turn into real possibilities for the project.

As William Blake wrote, a postcard of postcards in which these fragments meet.

My postcards are ‘other’ places of the imaginary that contain real places, amplifying some of their features, while rejecting others.

They tell of an idea of ‘Weak Architecture’ born as a reflection of codified images, an architecture emerging from context, from its forms, from the life that I imagine taking place inside.

It is always necessary to profane the original images as well as the old books and architecture magazines from which the fragments used in the montages are drawn. To profane in the sense that Giorgio Agamben means when he writes, that profanation neutralises what it profanes. Once profaned, that which was unavailable and separate loses its aura and is returned to use.’ [2]

The idea of returning images of cities to use, instead of consuming their effects, is a necessary attitude. Putting together fragments, mixing them to one’s memories in order to better assimilate them. Looking for other cities in the city, other works of art in its art, other architectures in its architecture. A writing in images, a personal history, which exploits imagination to tell other stories.

To quote Agamben again:

If, today, consumers in mass society are unhappy, it is not only because they consume objects that have incorporated within themselves their own inability to be used. It is also, and above all, because they believe they are exercising their right to property on these objects, because they have become incapable of profaning them.

The impossibility of using has its emblematic place in the Museum. The museification of the world is today an accomplished fact. One by one, the spiritual potentialities that defined the people’s lives — art, religion, philosophy, the idea of nature, even politics — have docilely withdrawn into the Museum. ‘Museum’ here is not a given physical space or place but the separate dimension to which what was once — but is no longer — felt as true and decisive has moved. In this sense, the Museum can coincide with an entire city […], a region […], and even a group of individuals (insofar as they represent a form of life that has disappeared). But more generally, everything today can become a Museum, because this term simply designates the exhibition of an impossibility of using, of dwelling, of experiencing. [3]

Therefore, profaning offers a new possibility for images to be inhabited once again.

The postcard as a form of museum of the real, as a tool to return to looking at the cities; and architecture represented, as a determined physical space.

This text is an excerpt from Luca Galofaro’s essay ‘Writing by Images, Thinking by Images’, published by Divisare.

Notes

- Sébastien Lapaque, Teoria della cartolina [Théorie de la carte postale, 2014] (Milan: Archinto, 2015).

- Giorgio Agamben, ‘In Praise of Profanation’, in Profanations [2005] (New York: Zone Books, 2007), 77.

- Giorgio Agamben, ‘In Praise of Profanation’, in Profanations [2005] (New York: Zone Books, 2007), 83–4.