Reality Modeled After Images: Architecture and Aesthetics after the Digital Image (2022) — Review

In Masons, Tricksters and Cartographers Sociologist David Turnbull reflects on the way technologies of drawing shape thought and action.[1] Cathedrals got built prior to international agreement on common units of measure, often without agreed plans, and without those people we now call architects. What scope for improvisation did individual masons have? How was that improvisation coordinated? His account places particular importance on two tools. First the ‘standard’, a fixed metal or flexible string ruler hung from gates of cathedral towns, allowing peripatetic builders to calibrate their work to the local metric system. Second the template, a piece of cut metal or timber that allowed profiles to be moved—cut and paste—from person to person, place to place. For Turnbull, these early building ‘standards’ allowed for the ad-hoc collaboration of diverse groups of labourers, prior to the existence of detailed or overarching plans. Discussing the production of cathedrals alongside that of world maps, and the outfits worn by court jesters, he makes some more general claims; if we look closely at any cultural product, we see it is shaped less by a single episteme, more by techniques and practices whose purpose is to stitch together diverse ways of thinking and acting.

Fellow sociologists Susan Leigh Star and Geoffrey Bowker draw on Turnbull’s account of these standards and templates when offering their own reflections on the way conventions shape collaborative work. Is it necessary for all those involved in the production of scientific knowledge—experts, technicians, cleaners, accountants—to think the same way? If not, how do they coordinate their work? Bowker and Leigh Star suggest that, like masons, they require ‘boundary objects’, tools and conventions that negotiate between different ways of thinking.[2] Like Gothic cathedrals, they argue that communities of practice are held together less by shared ways of thinking—by a common episteme—more by common technologies and practices that mean different things for different people. Disciplines like Science, Medicine and Architecture are riven with controversy and contradiction. Like cathedrals, world maps and jester’s outfits, they are motley.

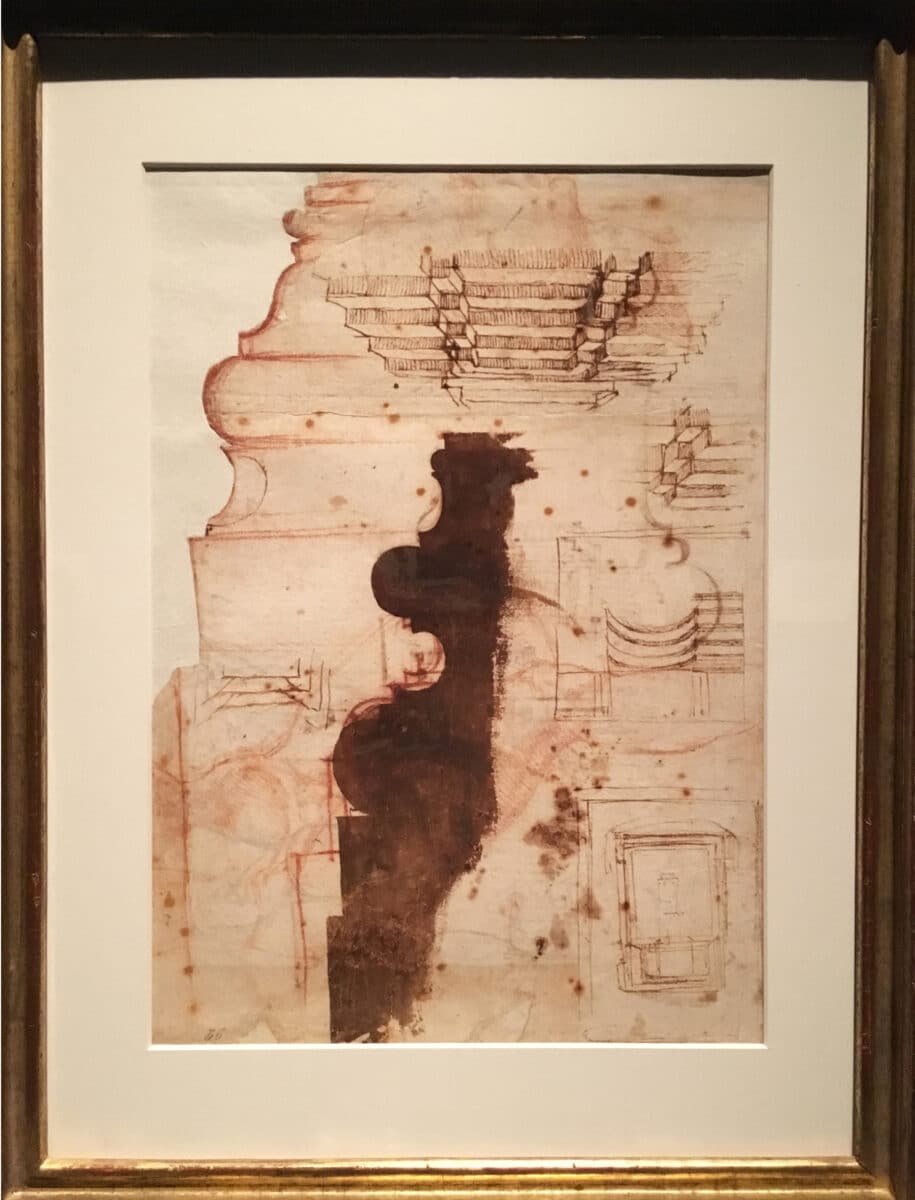

Michael Young’s Reality Modeled After Images: Architecture and Aesthetics after the Digital Image is also a reflection on how drawing conventions shape thought and action. It differs from that offered by the sociologists above—indeed it might seem directly opposed—as it concerns the way conventions come to have a special meaning for particular groups of people. Young begins his account with a reflection on those stone-cutting templates. During the Italian renaissance, these tools were called modani. They were associated with a practice called sciographia, or ‘shadow drawing’, through which masons shaded the side of the line that represented the material mass to be retained, distinguishing solid from void. Young suggests that this technique was also important for the emergent figure of the architect, who used it to render solid from void, not only in detailed drawings but also in general plans and elevations. Sciographia is the origin of that convention that came to be known as poché, that ‘familiar term for the horizontal sections of walls and piers appearing in plan, ordinarily blacked-in with India ink.’

Originally a shared tool for communication with and between masons, Young suggests that in its movement from construction site to design studio, this convention assumed a new significance. Like the gestalt-switch that occurs when a candlestick becomes visible between two faces, shadow drawing allowed a new conceptual object to snap into focus. In Bramante’s Parchment Plan, the void of space is rendered present in a new way, distinct from the solid mass that forms it. Young notes that in making this new thing present, something else had to be made absent. The poché plan is,

‘no longer a set of instructions for construction; instead it becomes an aesthetic device for making sensible the conceptual arguments of the architect… The sequences of construction, the specifications of material, the details of assembly, the computations of joinery, the surveying of site, the labour of building architecture; it is all removed, all hidden in the poché.’

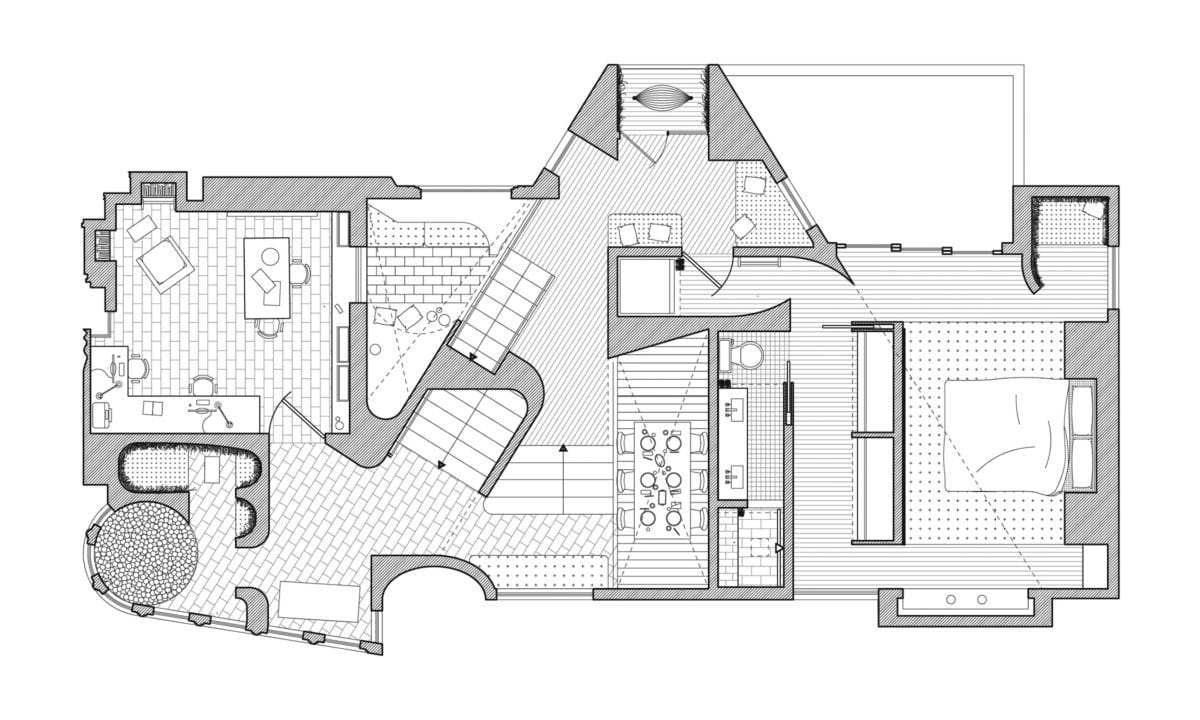

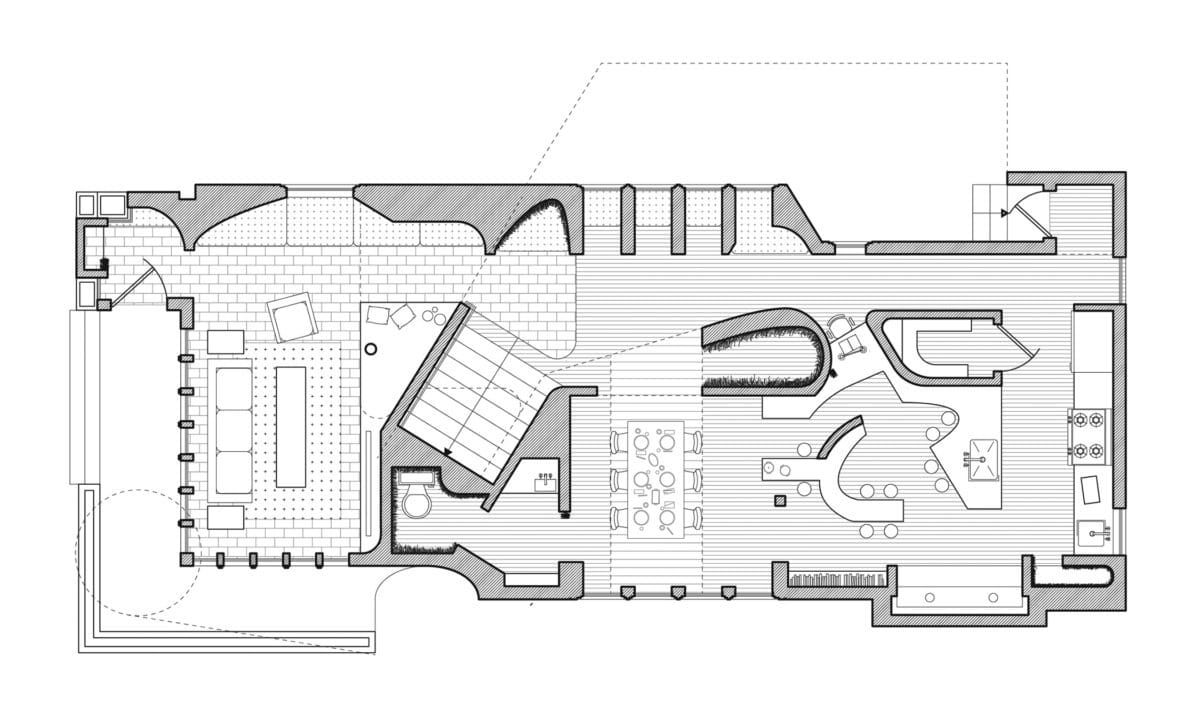

Formalised through the teaching of the École des Beaux-Arts, Young suggest that this convention has fundamentally shaped the purpose of architectural drawing, excluding construction information from its most important documents. Like others before him, Young asks us to recognise that drawing was both practically and epistemically important for the architect in their movement away from the construction site, defining design as something distinct and superior to manual labour. But Young also suggests that poché has shaped the architect’s relation to labour in more nuanced ways. Within the studio, practices of rendering supported a division of labour within the design process, as the ‘precise profile of the plan [is] inked by the designer, while the rougher work of filling in the outlined area could be done by beginning students’. Within finished buildings, those thick horizontal sections of walls and piers suggested locations in which servants and service stairs, chamber-maids and maid’s chambers, might be hidden. That is, Young suggests that the convention of poché is associated with and structures a consistent pattern of disciplinary thought, one that denigrates physical labour, be that the manual work of drawing, of construction, or of servicing buildings.

Young’s argument contrasts with that of Turnbull, Leigh Star, and Bowker inasmuch as he asks us to associate particular technologies with particular rationalities. His claim is that technologies and conventions of drawings have their own politic, one that is distinct from the intention of those who use them, or the ends they are put to. He suggests we can see this politic if we study the way in which drawing conventions come to have particular and closed meaning for a particular and closed group of people, acting as a kind of shibboleth. Again, the poché plan,

‘is not a ‘design’ drawing indexing the residue of procedural decisions. Nor is it a construction drawing explicating means and methods for building. It is an abstraction rendered for disciplinary consumption, that requires training to decipher, an expertise that distances the profession of architecture from the knowledge of both builder and layperson.’

Young describes this process of abstraction as central to the way in which disciplinary knowledge is formed. He thinks about this (following Boris Groys) as process of rendering ‘sacred’ conventions that are initially shared or common, and by suggesting (following Michel Foucault) that those conventions give the work produced within those disciplines their ‘discursive regularity’. Young makes that argument by following three conventions that were formalised by the École de Beaux-Art; poché, entourage, and mosaïque. His genealogy of poché charts a continuity-in-transformation that runs from Bramante and the Beaux-Art, through modernity, into contemporary modes of architectural representation. Kahn’s served/servant opposition is a relatively simple substitution, one in which the non-human labour of mechanical services replaces real servants in the mass of circulation cores, and the shadows of suspended ceilings. Corb’s free-plan implies its own gestalt-switch, but repeats the same opposition; space becomes the ground within which sculptural forms are placed, still concealing servants and services. LIDAR and photogrammetry are novel technologies of representation, but for Young they operate through the same template; reality is reduced to a surface that separates solid and void, known and unknown, the space of panoptic surveillance and its information shadow. That same template repeats in the work of contemporary North American practitioners, such as Clark Tenhaus, in whose speculative proposals we find blue mohair-lined cavities of space, carved from the margins of a client’s programmatic brief and the requirements of local building codes, offering pockets for ‘non-normative’ behaviour. Through this diverse range of examples Young suggests we can see a common ‘discursive regularity’, a consistent dividing line that separates and opposes the architect, space, design, comfort, knowledge, surveillance, and domination from the mason, matter, labour, services, ignorance, marginality, and escape.

The differing accounts of stone-cutting templates offered above have different emphasis and concerns, but they are not hard to resolve. Bowker and Leigh Star certainly recognise the special significance that particular techniques assume for particular groups; indeed, their work often begins by studying these mot justes. Nonetheless, their work remind us that to mean something outside of specialist that group—to have effects in ‘reality’—those techniques must also have looser, more ‘ill-structured’, meanings. Technologies and rationalities intersect, but they are not the same. Sciographia meant something to both mason and architect, something similar but also different. These differing emphases might be seen to map, more broadly, onto the legacy and perceived limits of Foucauldian scholarship. Later theorists have pointed to a reflexive trap within the search for ‘discursive regularities’. If we look for candlesticks, we see candlesticks, indeed it becomes hard to see anything else. Likewise, if we look for common patterns in thought, we find them. But if we want to understand the politics of a particular statement or convention, we need to consider the way it is translated, reinterpreted and reappropriated by a range of other actors. If we don’t, we risk becoming trapped by those ways of thinking we mean to critique.

Young is careful to guard against the untimely accusation that his study concerns the conventions of an elite Western European institution. Nonetheless, at times he does seem intent on extending the explanatory power of Beaux-Art concepts beyond the evidence he has to hand. This is most evident in the section on entourage—a term with little purchase beyond the Beaux-Art—which compares visually similar drawings but not necessarily consistent patterns of thought. The same concern might be evident in the examples above, also. What are the historical forces that shape the way labour is organised, in design, construction, and the maintenance of buildings, and have they been shaped by the convention of poché? In what way does LIDAR entangle design practice with the practical politics of surveillance? What kinds of ‘non-normative’ social practice are sheltered by the nooks and crannies of paper-projects? These questions are not answered, but they suggest a pattern of thought to reproduces and extends conventions of architectural thinking, rather than subjecting them to critique.

Central to Young’s study is an argument that architectural drawing, in its movement from the construction site, and in its transformation into the digital image, becomes less instruction for building, more object for internal disciplinary consumption. This is part fact, part artefact. Young chooses to study those drawings that have become canonical within the field, those that have, post-hoc, had most effect on intra-disciplinary conventions. His study of modani and sciographia are some of the few moments in which we see a drawing that answers to the information needs of other actors involved in building production. Young’s choice of material helps with one part of his ambition, but hinders another. Architects continue to make drawings, digital or otherwise, that communicate with others, and if we want to understand the politics of those conventions, their impact on ‘reality’, we need to consider their effects beyond discourse.

Over the last few years I’ve been part of project called Translating Ferro / Transforming Knowledge, reading and responding to the work of the artist, architect and theorist Sérgio Ferro as it is translated into English for the first time. Three volumes of his work are forthcoming; Architecture from Below: An Anthology, Design and the Building Site, and The Construction of Classical Design, edited by Silke Kapp and Mariana Moura, with translations from Ellen Heyward and Ana Naomi de Sousa. Ferro’s work also concerns the relationship between design and labour. His account differs from Young’s, though, in that it proposes its own gestalt-switch; Ferro’s project is to think about art, architecture and design from the perspective of the labourer. Seen ‘from below’ his work engages with some of the design practices and historical transformations discussed above, but from this changed perspective allows for a more detailed account of their practical and political consequences.

In The Construction of Classical Design Ferro offers an account of European cathedral building practices, mapping the succession of architectural styles into innovations in the division of labour. These include the emergence of the architect, and their gradual separation from the construction site by means of dessin, but also nuanced distinctions and struggles between masons. In early Gothic, Ferro suggests that sculpture and construction were socially and conceptually indistinct; relief features extend over and are continuous with structural components, completed collectively by the same workers. By the late Gothic, we see an increased division of labour, a distinction between art and architecture, supported by the convention of the niche. The mason who carves the niche—that poché of pochés—is not the mason who carves the sculpture; the function of this feature is to render those two forms of labour practically and conceptually distinct. For sure, those ‘thick horizontal sections of walls and piers’ that make up cathedrals are shaped by and shape divisions of labour; but in Ferro’s account we see how those divisions are drawn and constructed in reality, not only in the architect’s imagination.[3] In Concrete as Weapon Ferro turns to those transformations in labour practice associated with architectural modernity. Yes, the plastic quality of reinforced concrete allowed architects to emulate the affect of earlier periods of construction, but Ferro shows us that this material also supported dramatic changes in the politics of construction. He recalls the key role that masons and carpenters played in union activity in France during the late 19th Century, showing that the adoption of concrete construction was driven by its importance as a means of strikebreaking. The formwork of concrete construction was, in this context, a space intentionally evacuated of traditional know-how and its associated forms of political activism. The plastic possibilities of this medium were means to fill that void with deskilled labour, and with technical expertise that could be moved further away from sites, and safely into offices.[4] In Design and the Building Site Ferro provides his central thesis as to how and why design came to be separated from and to dominate over construction; architects, their drawings, and their attendant mot justes play an important role in capital, formally separating construction knowledge from those who embody it, replacing internal negotiation with an overarching plan, and so supporting the extraction of surplus value.[5] Central to that thesis is a contention that architecture is not a field defined by an autonomous episteme or set of internal disciplinary concerns, and that to think of it as such is to aid that project of separation.

Distinguishing Ferro’s work from that of other architectural theorists or historians, Silke Kapp, Katie Lloyd Thomas, and João Marcos de Almeida Lopes offer their own template. The majority of historians and theorists have been concerned with ‘Reception Studies’, with the way architecture is understood and discussed by its consumers, be they expert or lay. Ferro’s work points to an alternative approach—one they name ‘Production Studies’—that makes issues of material production, and labour, central to architectural analysis.[6] Young might be seen to contribute to that ambition, asking us to think about the way drawing conventions shape our attitude to labour. However, following Ferro and the sociologists above, we might suggest that if we want to understand how drawing affect reality, we have to look beyond drawings themselves. If we don’t—if we look for and see only candlesticks—the politics of drawing remain mysterious, obscure, in the shadow, blocked out with India Ink, covered over in blue mohair.

Notes

- David Turnbull, Masons, Tricksters and Cartographers: Comparative Studies in the Sociology of Scientific and Indigenous Knowledge: Makers of Knowledge and Space … History of Science, Technology & Medicine) (Taylor & Francis, 2000).

- Geoffrey C. Bowker and Susan Leigh Star, Sorting Things out : Classification and Its Consequences (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1999).

- Sérgio Ferro, The Construction of Classical Design, ed. Silke Kapp and Mariana Moura, trans. Ellen Heywood (MACK, 2024).

- Concrete as Weapon is included in the collection Sérgio Ferro, Architecture from Below: An Anthology, ed. Silke Kapp and Mariana Moura, trans. Ellen Heywood and Ana Naomi de Sousa (MACK, 2024).

- Sérgio Ferro, Design and the Building Site, ed. Silke Kapp and Mariana Moura, trans. Ana Naomi de Sousa (MACK, 2024).

- Silke Kapp, Katie Lloyd Thomas, and João Marcos de Almeida Lopes offer this framing in their introduction to Concrete as Weapon, published as an insert within Harvard Design Magazine No. 46, No Sweat (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Design Magazine, 2018).

Dr Liam Ross is an architect, and senior lecturer in architectural design at the University of Edinburgh. His recent publication Pyrotechnic Cities: Architecture, Fire-Safety and Standardisation considers the way architecture has been shaped by, and shapes, governmental approaches to fire and fire-safety.

Micheal Young’s Reality Modeled After Images: Architecture and Aesthetics after the Digital Image (2022) is published by Routledge. Copies of the book can be purchased here.