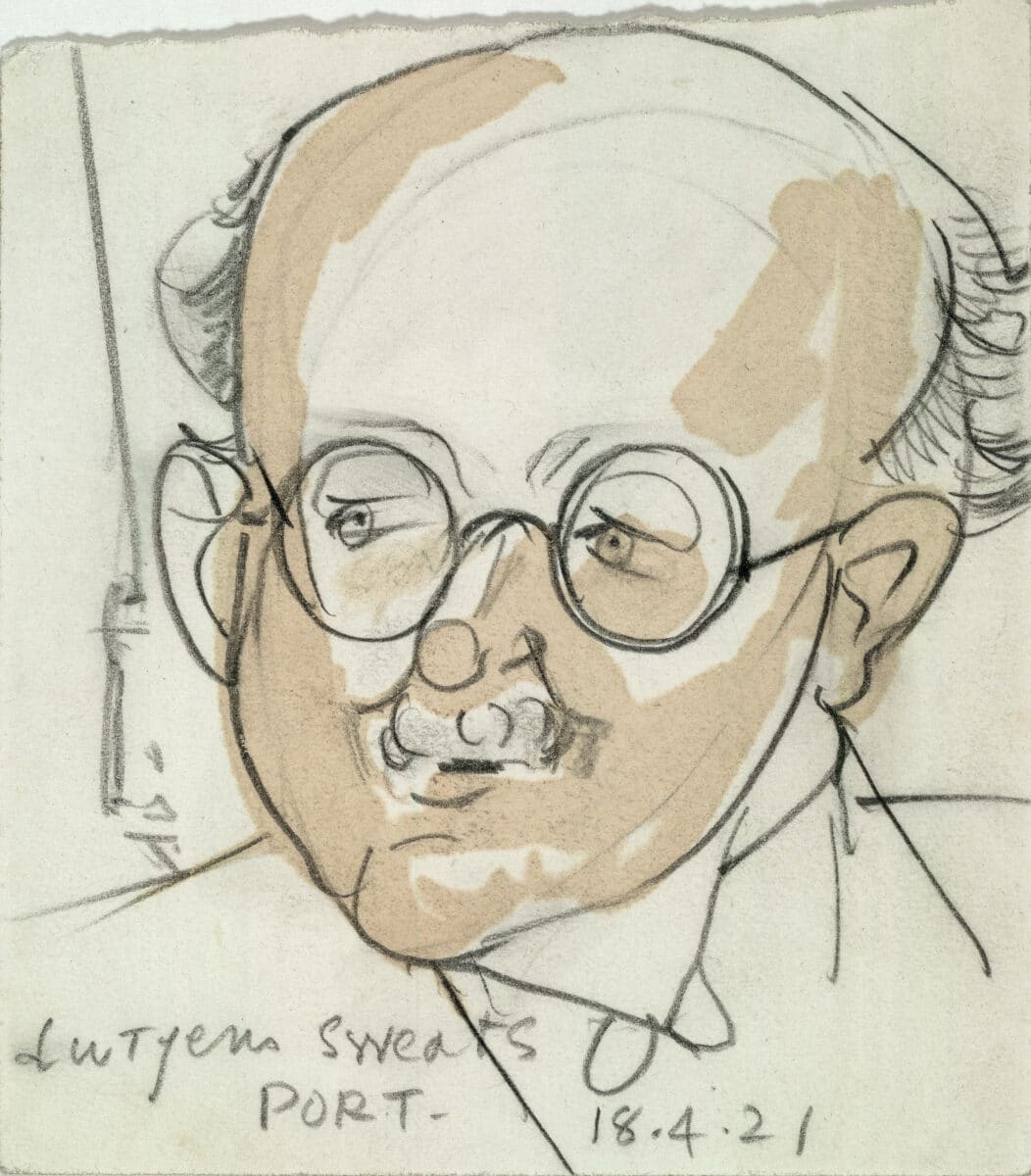

Sir Edwin Lutyens, by his Son

We have republished below an extract from Robert Lutyens’ short biography of his father, published in 1942, while Robert was serving in the RAF and two years before Edwin died.

The book itself is uncomfortable — an odd mixture of personal portrait, family background, and an attempt to at once theorize his father’s rejection of theory and to justify the architecture itself with reference to a theoretical framework derived, unconvincingly, from Robert’s own training as a designer.

The passage below addresses his father’s wit, both for what it was and for the protection it afforded him. The first paragraph is the saddest imaginable glimpse of any relationship between son and father — Oedipus replayed as drawing-room comedy.

Niall Hobhouse

I had proposed that we should lunch together at the Garrick Club, because I had obviously to ask father if he had any serious objection to the writing or the writer of this essay. But, when I broached the matter, he merely mumbled in obvious embarrassment: ‘Oh, my!’ — just as his father was used to do. Then, as the fish was served, he looked at me seriously over the rims of his two pairs of spectacles and remarked: ‘The piece of cod passeth all understanding’!

Having sought refuge in a pun he did not give me an opportunity of renewing the subject: the fleeting opportunity had gone, when as usual he waved to some solitary member, whose name he had entirely forgotten, to join us. By the end of lunch he was cracking innocuously bawdy jokes over a decanter of port with a handful of cronies, in whose company he expanded in genial fellowship.

I have not the smallest doubt that father’s wit, which is partly a conscious facetiousness and in part due to an extraordinarily literal mind, owes its origin to his acute shyness in the difficult relationship of architect and client.

A long-legged young man on the hunt for a job bicycled one day across Hindhead to call on an aristocratic personage who was known to entertain the desire of building a very small house with very large rooms in it. It was a lovely May morning. The gorse was in bloom and the cuckoo was calling from a birch coppice over the common. On arrival my father was presented to the owner who offered him a slate on which evidently to write his greeting. He was overcome with confusion. Then he wrote: ‘Have you heard the cuckoo?’ She rebuked him with a glace. ‘Young man,’ she replied, ‘I haven’t heard anything for twenty years!’

There is no good reason why choice should fall on any one architect, if he be comparatively unproved. Here is one of the absurdities of a system of payment on a prescribed scale of fees. There is no inducement whatever to select a young man in preference to one of greater experience; particularly as a younger man can have so little to show in proof of his claims. The painter can hang his unsold pictures to the wall in disdain to public disregard. The author can file his rejected manuscripts and try again. But the composer needs an orchestra, and the architect requires a client.

His very first essay must be at someone else’s expense; while he is under the ‘ethical’ obligation to charge as much for his inexpert services as would the leading luminary of the profession. He is therefore obligated to sell, in the first instance, not only his talent but himself. He has to cajole, to flatter, to pursue. He is often betrayed by over-anxiety. If he be honest and confident, then he must place in jeopardy the cherished opportunity by his insistence on his own interpretation of instructions. He must inspire trust and oppose his client at the same time; and he must accept responsibility for the miscarriage of his plans, no matter whether or not he is to blame.

I do not wish to suggest that father’s exuberant punning is not natural to his temperament, or that his wit is less native than acquired. He possesses the gift of fixing his attention on a similarity of word-sounds without considering their meaning, combined with a temperamental inability to treat seriously the sort of imponderables which agitate the thought and conversation of so many people. At the same time he has turned his apparent frivolity to triumphant account in innumerable contests. He has used it for evasion as well as to disarm; thus conceiving of his duty to himself and to his client. Nor has his wit lacked a cutting edge. Lord Inchcape was no more than mildly amused when father proposed that the inscription on his tomb should be surmounted by the letters: ‘R.I.P. & O!’ The late Lord Birkenhead, hearing of this, asked him what sort of design he would suggest for his memorial. Father’s retort was quick and biting. ‘A Rolling Stone!’ he answered.

Lady Harding was angry with him for some wilful misinterpretation of instructions in the early days of Delhi’s building. So he wrote to her in gay contrition to tell her he would sue for forgiveness by washing her feet with his tears and drying them with his hair. ‘It is true,’ he wrote, ‘that I have very little hair. But then you have such very little feet!’

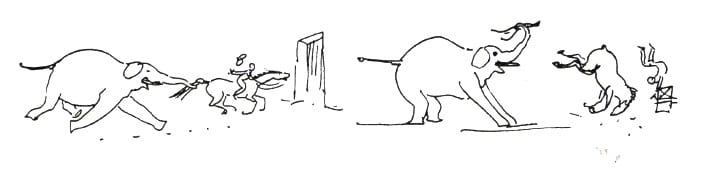

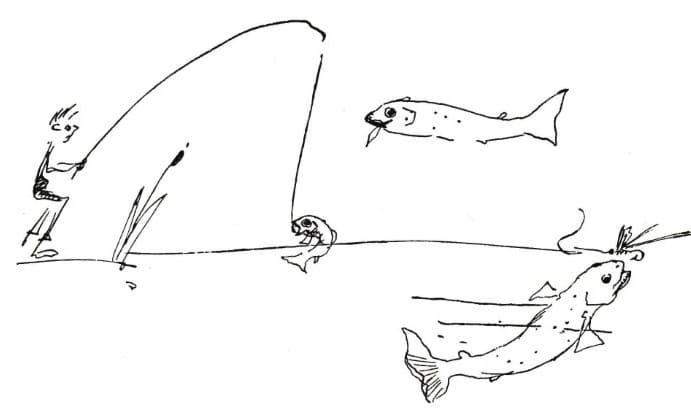

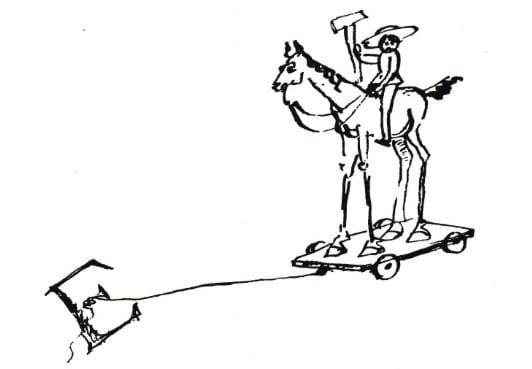

Here is the clue to his constant claim on the affectation of women, who are no longer wooed with sonnets. He could resort to profuse flattery without offence, because he was devoid of any challenge of sex. By the same token, in joke and in drawing, his indecency is proverbial. But it is all so impersonal, so unfelt and insubstantial, that it seems to issue from the lip and pencil of a Rabelais turned spiritual elf!

The legend is current in India that a dynasty shall fall when the bells ring. This has been given as the reason for the dependent clapperless bells which replace the more orthodox volutes on the beautiful Delhi capitals. But it is without the authority of mythology. The late Duke of Connaught, who visited Viceroy’s house during the building, asked father why he had hung bells from the tops of the columns. Why? – indeed why? What reply is possible to such a question? – a question promoted by slightly condemnatory curiosity. How explain in any communicable terms the treatment of some one factor of design: the joint issue of experience and of something far more personal? Father would never dream of dealing harshly with the ignorant, and would hesitate to give unnecessary offence to useful patronage. In this instance he besought his wits for an answer; and so the legend grew. ‘Did you ever hear, Sir, of the Mogul superstition that the ringing of bells proclaimed the end of the dynasty?’ he asked. ‘That is why my bells are made of stone!’

The Duke was delighted with the loyalty of the conceit. The rest who heard it were not to know that so circumspect a fiction was without foundation in fact.

I have said that my father is shy and distrustful of any emotional instability. His reticence is characteristic and peculiarly English, as is his suspicion of ‘foreigners’. I have said that my father is shy and distrustful of any emotional instability. His reticence is characteristic and peculiarly English, as is his suspicion of ‘foreigners’. He is fundamentally respectable and deferent to the successful products of competitive society. These are personal idiosyncracies and of little importance. His life is a pattern of conformity, although his habits are eccentric. But even such small departures from the conventional are due in the main to his withdrawal from participation in the leisured pursuits of his friends. His work has demanded complete absorption, permitting neither distraction nor relaxation. Inversely, the demands of flesh and spirit were so little insistent as to offer no challenge to his pre-occupation. He has never taken a day of rest or exercise; music on the whole bores him, and the theatre makes him cry – at the spectacle of tragedy and comedy alike! He smokes a lot of cool little pipes that are solemn alight: one of his most personal gestures is tapping out a newly-filled pipe on his heel into the waste paper basket. He reads little. He still wears the starched collars of the 90s on all occasions. His beautiful hands are invariably begrimed with pencil dust, and he pares his nails with a pruning knife. When he is not actually working, he plays patience, or else sits absorbed over a jigsaw puzzle. It is difficult to know what he is thinking about at such times. He is invariably silent: not formidable – he is never that; but turned inwards and vaguely unhappy, I suspect, and perplexed by the incontinent demands of a restless and dissatisfied age. He is easily depressed. But his wit is his defence; and his fooling is a means of assault on the stubborn resistance of the unimaginative.

Excerpted from Sir Edwin Lutyens: An Appreciation in Perspective by His Son, published by Country Life in 1942. The small sketches are taken from Edwin Lutyen’s personal letters. With thanks to the Estate of the late Robert Lutyens.

– Annette Carruthers, Mary Greensted and Barley Roscoe