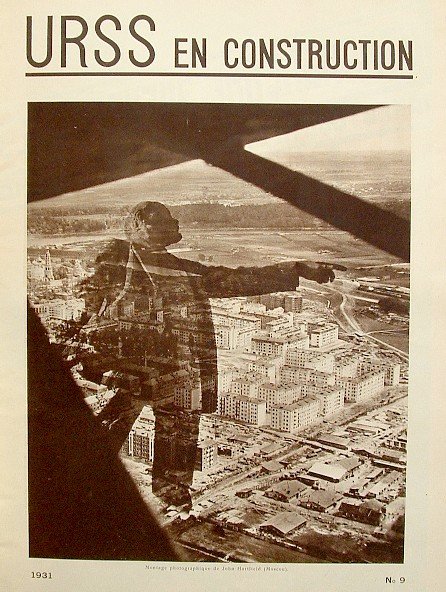

USSR in Construction No. 9 1931

Constructing a Fantasy of the New Moscow through Architectural Photographs

In June 1931 Lazar Kaganovich, the Secretary of the Communist Party Central Committee gave a speech to the Moscow plenum entitled, Za sotsialisticheskuiu rekonstruktsiyu Moskvy i gorodov SSSR (On the Socialist Reconstruction of Moscow and other Socialist Cities of the USSR). The speech provided a detailed report on the urban development priorities that would lead to the socialist reconstruction of Moscow. It was passed into a resolution to begin the process of reconstructing Moscow to make it a modern socialist capital city, and to establish it as a model for other cities throughout the Soviet Union. It also provided the framework for what would be officially approved in July 1935 as the General Plan for the Reconstruction of the City of Moscow; a major urban planning scheme intended to overhaul the entire city in both plan and architectural aesthetic.

Kaganovich’s speech was widely promoted in the Soviet press as an introduction of things to come in the socialist transformation of the Soviet capital. Numerous publications devoted special editions to commemorating the speech by documenting the changing architecture of Moscow through the theme of the New Moscow. These early representations of the New Moscow in print promoted socialist progress through avant-garde architecture that was built before 1935.

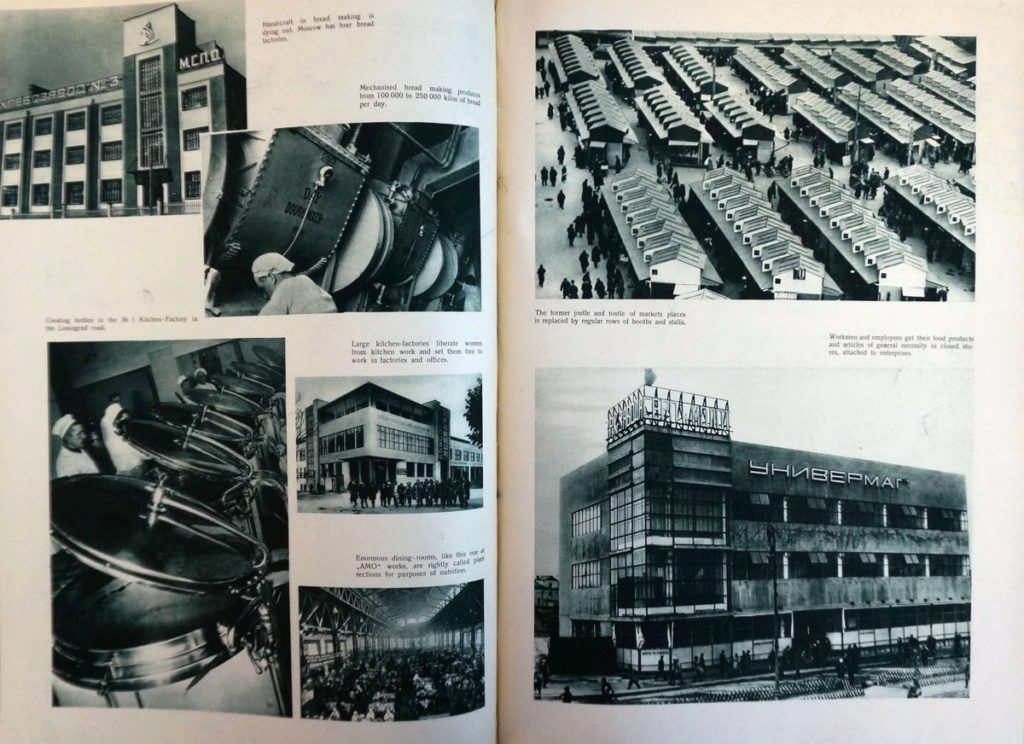

One of the first, and most comprehensively illustrated publications to commemorate Kaganovich’s speech and promote the New Moscow is the September 1931 issue of SSSR na Stroike (USSR in Construction) – a large format, photo-illustrated monthly magazine devoted to promoting the progress of the Five Year Plans. This issue was designed by John Heartfield. He had been invited to Moscow in 1931 to stage an exhibition of his photomontages and give a series of lectures about designing posters and periodicals. Though the magazine was produced and presented under the guise of objective documentary, its design and content construct a city through selection and omission. Through the presentation of the many facets of the New Moscow, that included improved transportation, increased housing and green space, and new socialist building typologies such as the worker’s club, and mass dinning halls, this issue of SSSR na Stroike connected architecture with the daily lives of Soviet citizens to show how socialism was transforming life in Moscow for the better. Furthermore, it contributed to the construction of the New Moscow as both an architectural and symbolic project. Page after page, Heartfield constructed a fantasy of a rational, clean, and modern city that had been facilitated mostly by avant-garde architecture.

The presentation of the new Moscow follows the narrative set out in Kaganovich’s speech and seeks to provide visual evidence that progress on each of the central themes of the proposed reconstruction is already underway. It does so despite the fact that no formal plans had been made, and discussions about the architecture of the New Moscow had not yet begun.

The opening page introduces Moscow as a city that is rapidly developing from old to new (Fig. 1). It is a photomontage of aerial photographs of new residential complexes in Dubrovka and Usacheva Ulitsa on the outskirts of Moscow. Traditional Orthodox church spires are still visible to the far left of the image, but the emphasis lies on the new buildings and open space, soon to be developed, to the right and top of the photograph. Heartfield overlaid a photograph of Lenin onto the Moscow urban environment as if to suggest he was overseeing the construction taking place below. The inclusion of this oft-repeated image of Lenin pointing ahead in the distance was a near ubiquitous reference in publications from this time. It was employed in this instance to reinforce the role of socialist ideology in the architectural transformations taking place in the background and in the subsequent pages of the magazine.

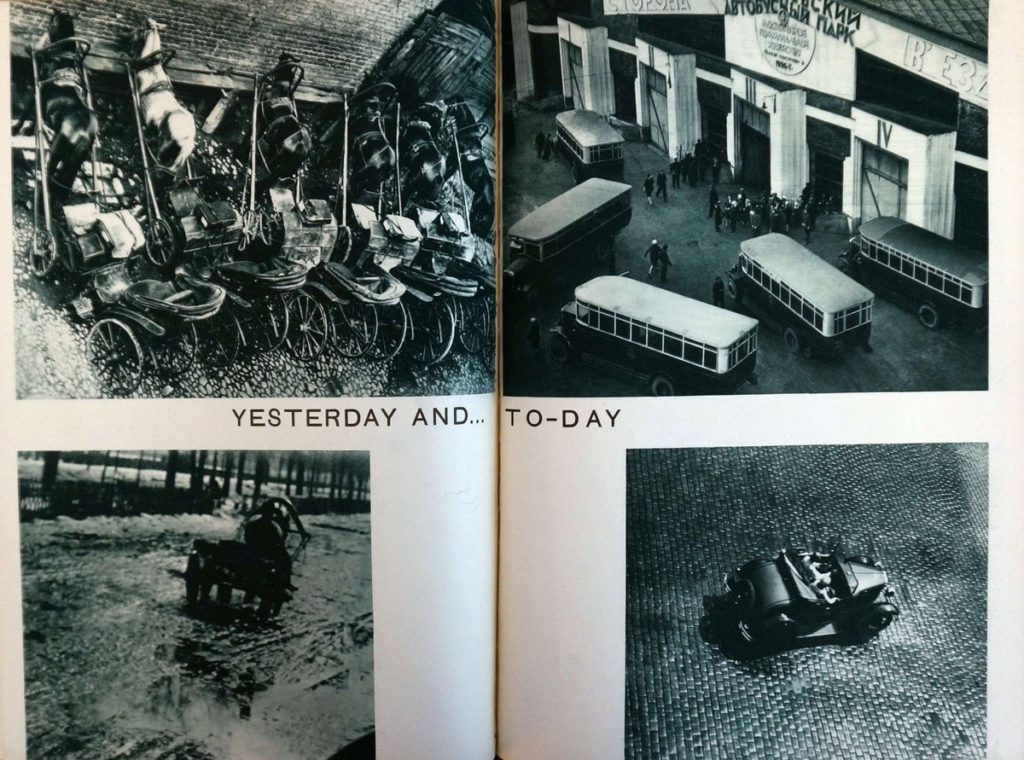

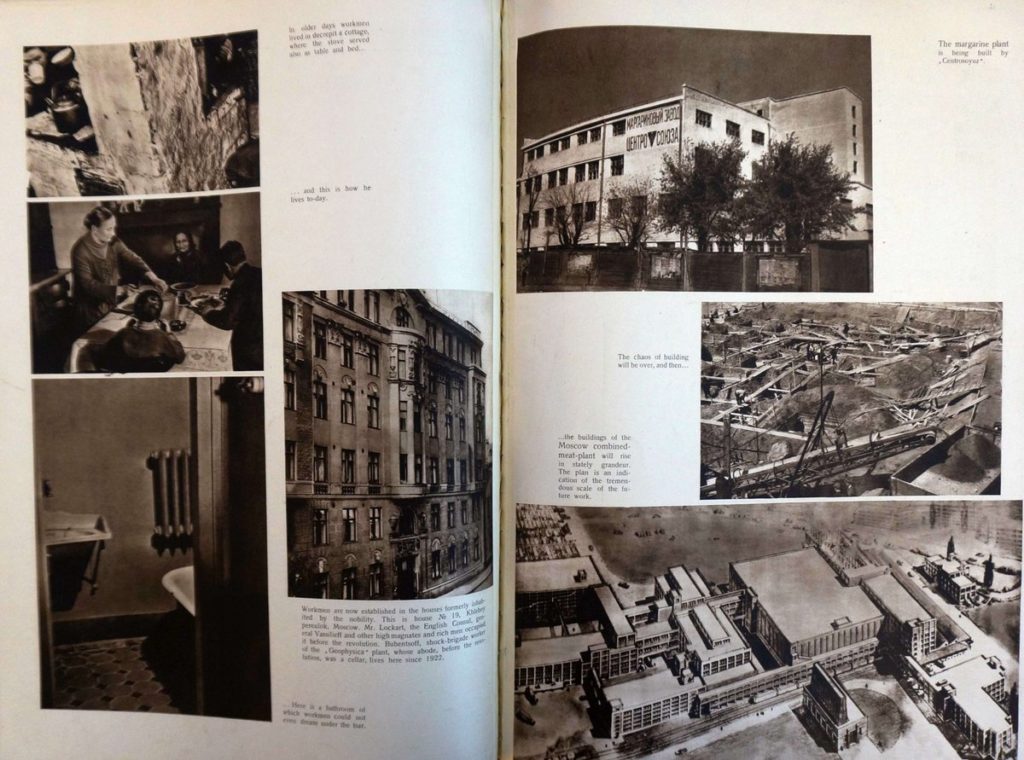

The central spread presents a sharp contrast between the old and New Moscow, which is represented by Konstantin Melnikov’s Bakhmetevski bus garage (1927), glistening pavements, and a new convertible car, in contrast to the dark, muddy, and ramshackle streets, occupied by horses and carts (Fig. 2). The rest of the issue features quotations from Kaganovich, Party officials, and engineers, combined with statistics to provide the necessary documentary elements that weave seamlessly with the narrative of rational, socialist transformation. Photographs of new factories, mass kitchens and dinning halls, along with worker’s clubs and housing fill each page, giving a sense of the comprehensiveness of the plans for reconstruction. The buildings featured include iconic examples of Soviet avant-garde architecture, including The Electric Institute of the USSR by A. Ficenko (1926), the Shabolovskaia radio tower by the engineer Vladimir Shukov (1918), MosGES (First Electrical Plant, by Zholtovsky, 1927), The House on the Embankment by Boris Iofan, completed in 1931, and Melnikov’s Rusakov Worker’s Club (1927) (Fig. 3).

In a departure from previous and subsequent issues of SSSR na Stroike that emphasised the process of transformation from a rural outpost to industrial centre through myriad photographs of construction sites, this one focuses almost entirely on built projects. One of the few examples of an unfinished project is the photograph of the Tsentrosoiyuz margarine plant that is introduced by the caption, ‘the chaos of building will be over, and then…’ Next to the text is a photograph of a construction site, and below that, is a drawing for a modernist combined meat plant. The caption continues where it left off, ‘…the buildings of the Moscow combined meat plant will rise in stately grandeur. The plan is an indication of the tremendous scale of the future work.’ All three images are washed in sepia tone, and the photographs are softened so that each of the three images shares the same quality, and thus appear to be equated with one another. Though the drawing is included to demonstrate a future vision for construction, and the photographs are there to document reality, their appearance suggests that there is no distinction made between the two forms of representation. As the text confirms, this future work will be completed, and therefore the drawing is as much a piece of documentary evidence of progress as the photographs.

By using built projects to illustrate the proposed future development of the city, this issue of SSSR na Stroike disseminated an image of the New Moscow that bears little relation to the ultimate aesthetic outcomes of the planning and construction project that would emerge after 1935. The image of the New Moscow that is presented is one of a city filled with brand new buildings that stem from avant-garde architectural principles developed by the Constructivists and Rationalists. This however, is not the New Moscow that emerged in the General Plan in 1935, in which the architecture of the newly designed city would be characterised by a return to historicist architectural styles, and a trend toward large-scale monumental buildings.

The consistent use of photographs of completed buildings to illustrate an immense urban planning and architecture programme that was under development at the time, added to the symbolic effort of the reconstruction and aided in building a fantasy of the progress of the New Moscow, despite the realities of the programme for reconstruction. Publications such SSSR na Stroike that produced and reproduced these images of the New Moscow made use of photographs to both accurately record a changing reality and to affect, or produce it.

– Tim Abrahams