W. R. Lethaby: Philip Webb and His Work

This is the fifth and final text in this series, where Hugh Strange visits key texts throughout W. R. Lethaby’s life.

Philip Webb was William Lethaby’s great hero; he considered his life and work the model for an architect. Webb was a generation older than Lethaby, and the two men most likely first met at one of Webb’s political lectures in 1883. But it appears to have been in 1891 that the two men became close friends, when Lethaby moved his newly formed office to Gray’s Inn Square, across the gardens from Philip Webb’s chambers. For around ten years, until Webb’s retirement and Lethaby’s move away from practice at around the same time, the two remained in regular contact, with Lethaby a frequent visitor to Webb’s studio. During this period, as well as a broader impact on Lethaby’s thinking, detailed design influences are also apparent, perhaps most specifically in Lethaby’s designs for the large house at Avon Tyrrell that appears close to both Webb’s Rounton Grange project in plan layout, and Webb’s Standen (1892-94) in appearance, evidenced in the repetitive end gables the projects share to their garden facades.

The two men also shared much in common. Throughout their lives in practice, they both ran small practices with just one or two assistants. But while Lethaby’s career in private practice was relatively brief, completing six buildings in a period of just over ten years, and later focusing on education and writing, Webb didn’t author texts and never taught. Instead, his long career was very much focused on the construction of buildings in practice. Webb famously only took on a very few buildings at a time, such that he could be intimately involved in every detail of their construction. His buildings and drawings reflect this dedication to construction and refinement of detail, the results not fetishizing craft, but rather through care and understanding, aspiring for ‘sound building’. Following Webb’s retirement from practice in 1900, until his death in 1915, the two remained close friends and Lethaby often visited his new home in the Sussex countryside. He appears to have been the obvious choice as Webb’s biographer.

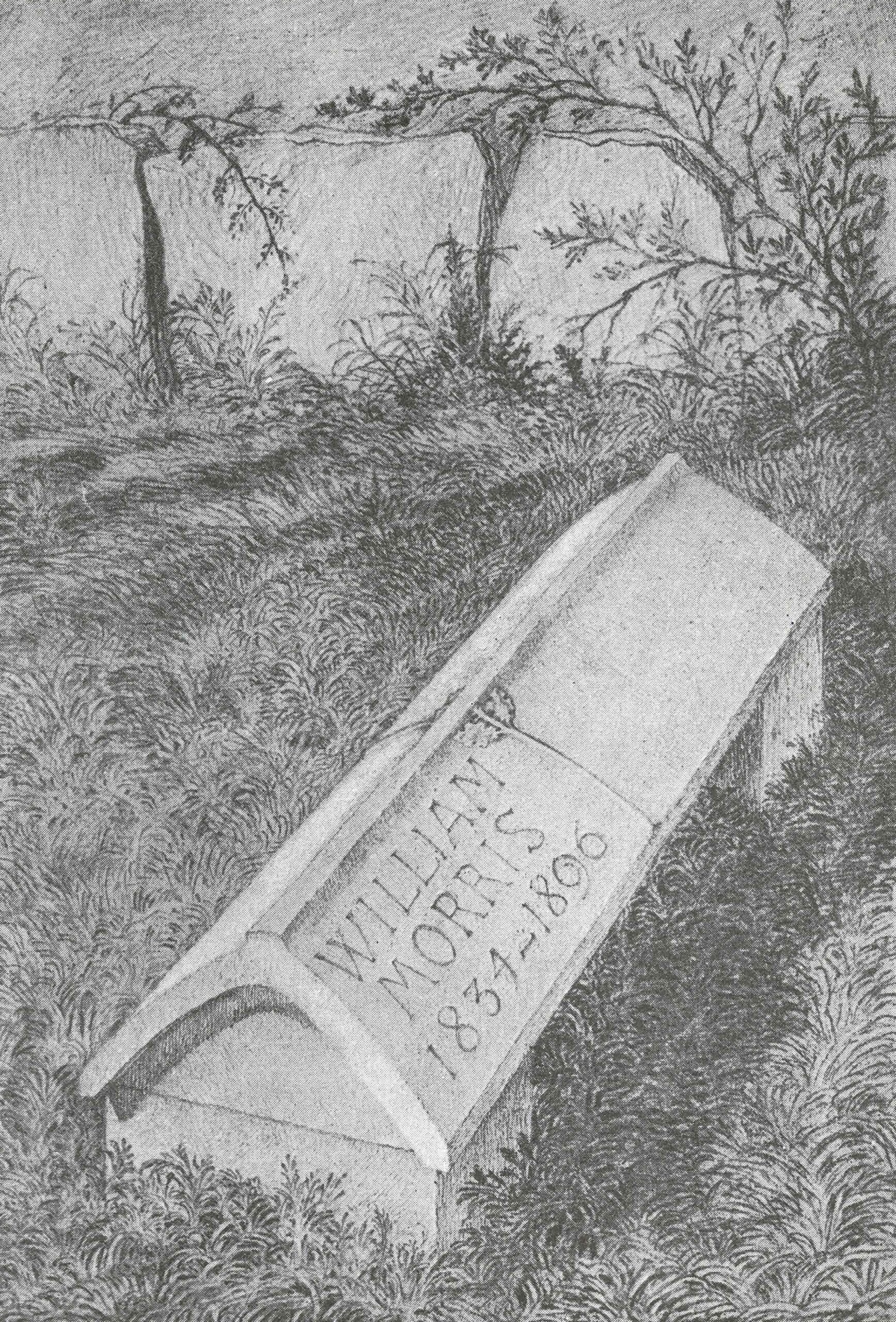

First published as a series of articles in 1925 for the journal The Builder, his biography of Philip Webb was later collated into book form and published in 1935. The focus of the text is on Webb’s working life: his buildings, his thoughts and his values. Webb grew up in Oxford in the 1830s and returned in the 1850s to work for G. E. Street, where he was to meet William Morris. Their friendship resulted in Webb’s first major architectural commission, for Morris’s house at Bexleyheath, The Red House (1959-60), but became a lifelong back and forth of collaborations and shared endeavours, particularly focused around the Morris Firm and the Society of the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB). The second edition of the book, from 1979, added three chapters from the R.I.B.A. Manuscripts, written by Lethaby but not initially included, on ‘Webb’s Socialism’, ‘Talks and Some Sayings’, and ‘Letters on the Arts.’ As evidenced through these additional chapters, it transpires that Webb was as intensely involved as Morris was in various Socialist groups throughout this time.

The book’s chronological structure is broken at the midpoint by an extended chapter titled, ‘Some Architects of the Nineteenth Century and Two Ways of Building’. Here Lethaby describes, in turn, the works and approaches of the key British architects of the era, dividing them into two broad categories, ‘One group turns to imitation, style “effects”, paper designs and exhibition; the other founds on building, on materials and ways of workmanship, and proceeds by experiment. One group I would call the Softs, the other the Hards; the former were primarily sketchers and exhibitors of “designs”, the others thinkers and constructors.’ Lethaby places Webb in the lineage of Butterfield, as one of the ‘Hards’, and an architect primarily concerned with building. But he sees Webb as on another level to his contemporaries altogether, the only architect of the age who, following Ruskin, sought, ‘a new kind of ethical dignity.’

What makes Lethaby’s biography of Webb so very engaging is that accounts suggest the two men were very similar in character, their colleague C.R. Cockerell noting they were, ‘exactly the same type, unself-seeking, far-sighted, generous-minded men.’ The book, aptly described by Andrew Saint as, ‘within the Boswellian tradition’, teaches us as much about Lethaby as it does Webb; we understand Lethaby’s values and views through those he admiringly recounts of Webb. And, I believe, these remain compelling and relevant, the book full of the two men’s concise wisdom. A few brief insights I have extracted from the text are:

That through Lethaby’s description, we learn how Webb immersed himself in construction – ‘Architecture to Webb was first of all a common tradition of honest building.’

How Webb believed, ‘Materials must be used so as to express their essential qualities; these essential qualities are what rhythm is to poetry.’

How Webb had what might be described as a Mies-like sense that a building should be good, rather than interesting – ‘I never begin to be satisfied until my work looks commonplace.’

And how, as many other designers of the Art & Crafts Movement, Webb grappled with his distance from the building site, aware despite his extraordinary draughting skills of the role drawing played in this distancing – ‘He said that the ability to make picturesque sketches was a fatal gift to an architect.’

And finally, one of my favorite quotes, that engagingly qualifies the undoubted dry, puritanical streak of the two men, ‘Yet another of Webb’s thoughts to which he would frequently recur was that all the greatest art preserved some strand of primitive frankness and an element of wonder.’

– Hugh Strange