W. R. Lethaby: Apprenticeship and Education

This is the fourth text in this series, where Hugh Strange visits key texts throughout W. R. Lethaby’s life.

The building sites of London in the late nineteenth century desperately lacked adequate skills, and this need was being addressed neither on the job nor through appropriate training. The first prospectus of The Central School of Arts and Crafts of 1896 made clear the school’s aspiration to rectify the issue:

‘There is no intention that the school should supplant apprenticeship – it is rather intended that it should supplement it by enabling its students to learn design and those branches of their craft which, owing to the sub-division of processes of production, they are unable to learn in the workshop.’

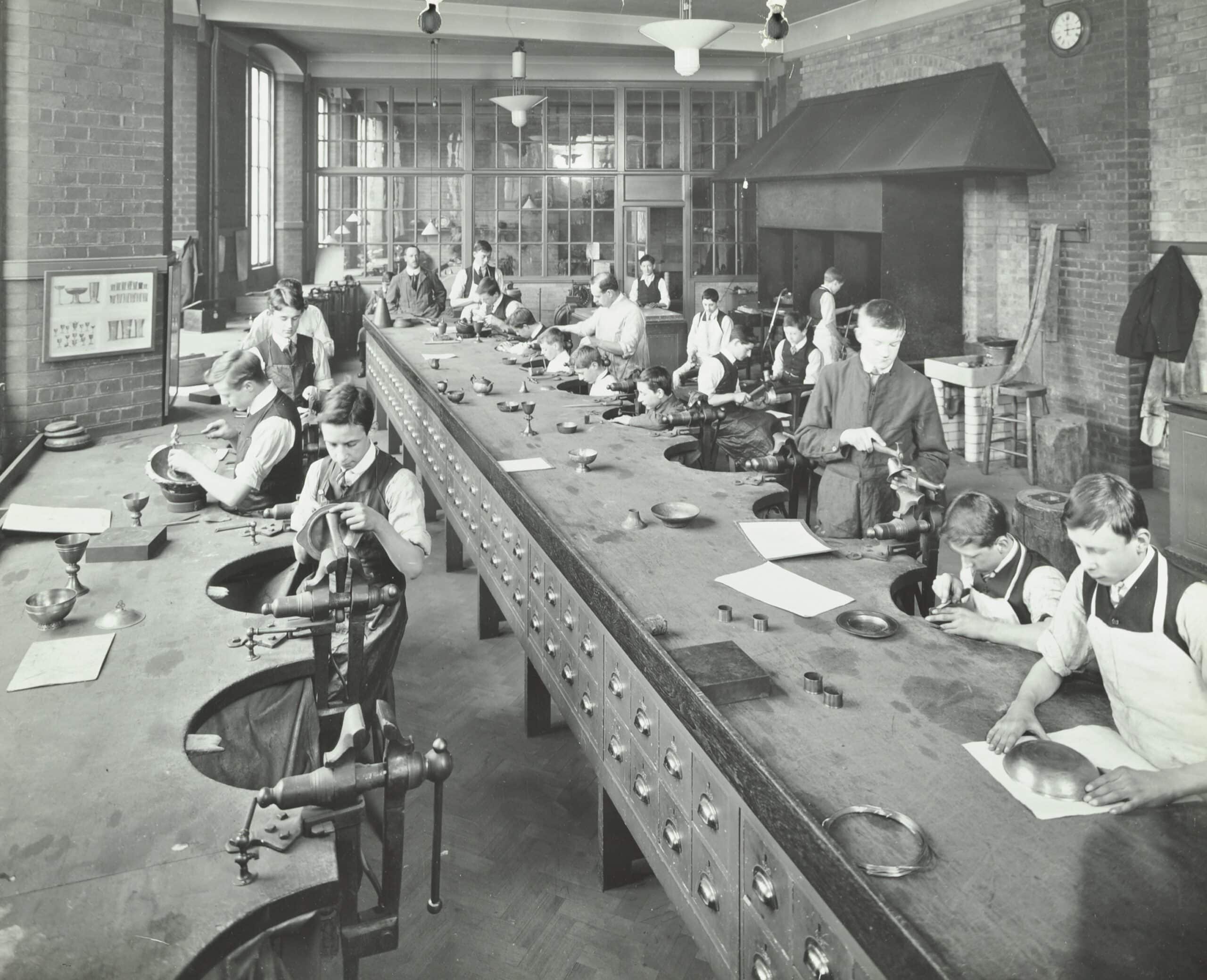

William Lethaby was employed as art inspector to the newly established Technical Education Board of the London County Council in 1894, and soon after when the Central School of Arts and Crafts was set up in 1896, was appointed one of its founding co-heads, before becoming its sole principal from 1902. Initially based in Regent Street, new premises were opened in Holborn in 1908, with Lethaby remaining in his role until 1911. Supported by a like-minded team of tutors of his choosing, the school sought to train both architects and craftsmen. New forms of teaching pioneered at the Central School were radical and experimental at the time, rejecting bookish learning and focussing instead on working directly with materials and tools within a workshop environment. The syllabus sought to nurture handcrafts – by 1902 there were 31 classes – including leadwork, textiles, gilding, calligraphy and jewellery. Architecture classes were led by Halsey Ricardo, and, with some irony, were apparently held beneath a leaky glass roof, such that students had to use umbrellas inside to stay dry when it rained. To counter the separation of design and production, students throughout the school were encouraged to develop projects from conception through to completion. Significantly, all teaching classes occurred during the evenings to accommodate the working lives of staff and students, and despite the general fees applicable, admission to the school was free for apprentices.

The Central School of Arts and Crafts nevertheless still taught architecture students apart from the building trades. This separation was addressed more directly at the School of Building, established in 1904, and based in Brixton. Once again Lethaby was instrumental in establishing the goals of the school’s syllabus. In contrast to the Central School, and to the various polytechnics that taught trade skills and the universities where architecture was being established within an environment of scholarship, architects were here taught alongside the workmen of the building trades. With the Medieval building workshops of the guilds certainly in Lethaby’s mind, the syllabus provided for architects, foremen and tradesmen – including bricklayers, plasterers, carpenters – to study alongside each other, participating in their own courses in view of each other, and in close enough proximity to work together on shared projects. The School of Building was located within a redundant swimming bath, and workshops for individual classes surrounded the main space of the swimming baths. Here, in the Large Hall, students could work on full-scale mock-ups of construction works. As well as providing the opportunity for collaborative working, this setting allowed practical learning to be aligned with Lethaby’s idea of architecture: experimental building research in materials and structures. The work developed by Lethaby in these schools was closely followed by Hermann Muthesius, author of the influential text The English House, and resident between 1896 and 1903 at the German Embassy in London. Muthesius described Lethaby’s Central School of Art and Crafts as, ‘probably the best organised contemporary art school’, and, on returning to Germany, went on to become a key figure in the establishment and development of the Deutscher Werkbund of 1907, channelling the workshop ethic he had admired in Lethaby’s curricula.

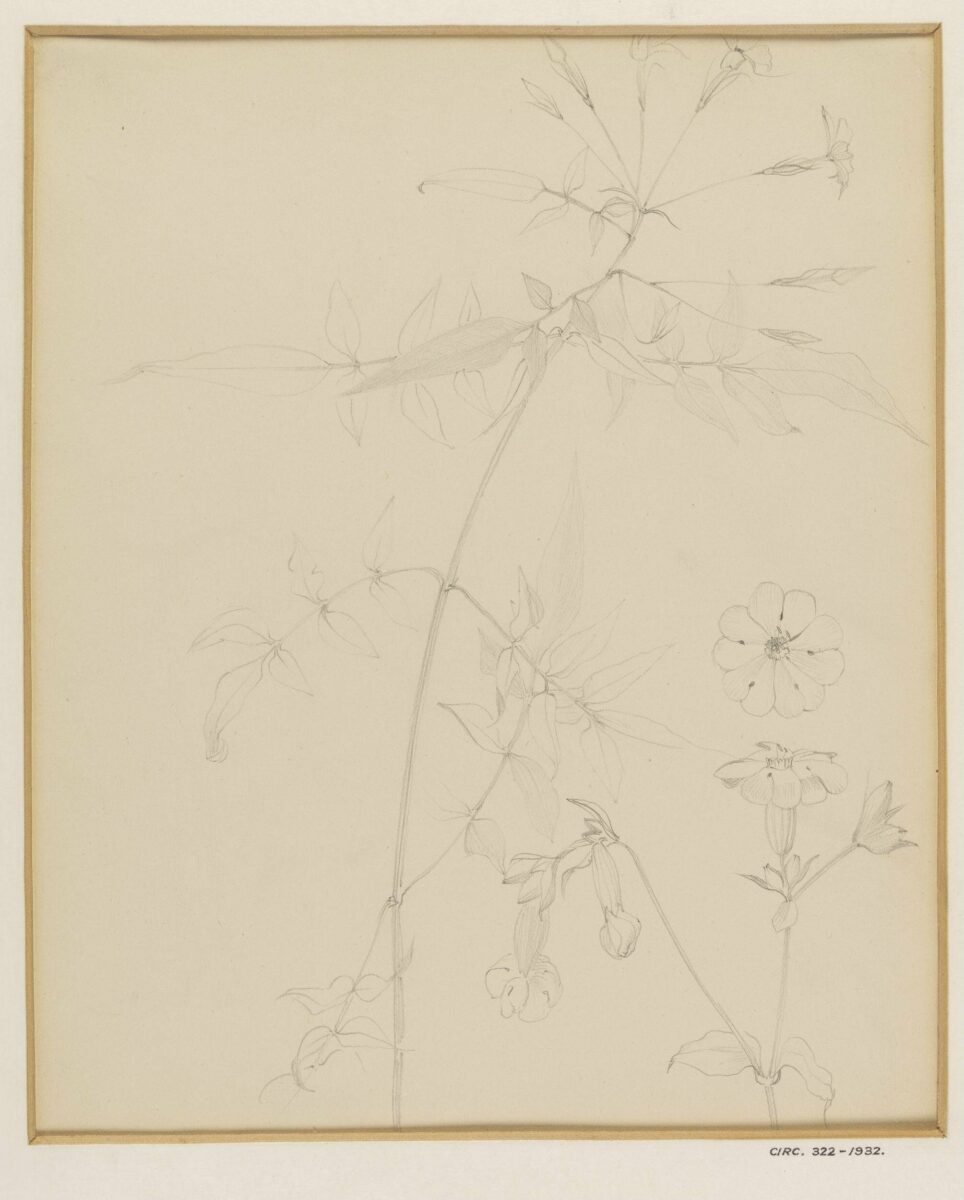

By the turn of the century, Lethaby had wound up his architectural practice, his last projects being the construction of All Saints’ church at Brockhampton, and the remarkable, but unsuccessful competition for Liverpool Cathedral in 1902. From this time onwards, perhaps appreciating the opportunity for greater influence, his focus was on teaching and writing. First published in 1922, Form in Civilization: Collected Papers on Art and Labour, presents a series of significant essays of this period. Interestingly, Lewis Mumford’s foreword to the second edition of the book in 1957 acknowledges Lethaby’s importance within the Arts & Crafts movement, describing him as having, ‘an honoured place as one of the apostolic succession that began with Ruskin and moved on through William Morris.’ Included within the collection are three essays of relevance to Lethaby’s teaching ethos, perhaps the most noteworthy being Apprenticeship and Education. This paper was presented at the International Conference on Drawing in South Kensington in 1910, which perhaps explains the text’s particular focus on drawing. Lethaby here writes against learning about drawing, extolling instead the merits of learning drawing by drawing. Significantly, he also suggests that drawing be allied to the learning of a craft, and best undertaken as a vehicle to understand that craft, ‘All I have to say is an amplification of the idea that all education should be apprenticeship, and all apprenticeship should be education.’

You can read all of Form in Civilization: Collected Papers on Art and Labour here. Lethaby’s essay on ‘Apprenticeship and Education’ is on page 139.

– Basile Baudez and Maureen Cassidy-Geiger