Halsey Ricardo

A pathetic eloquence to those that can hear them

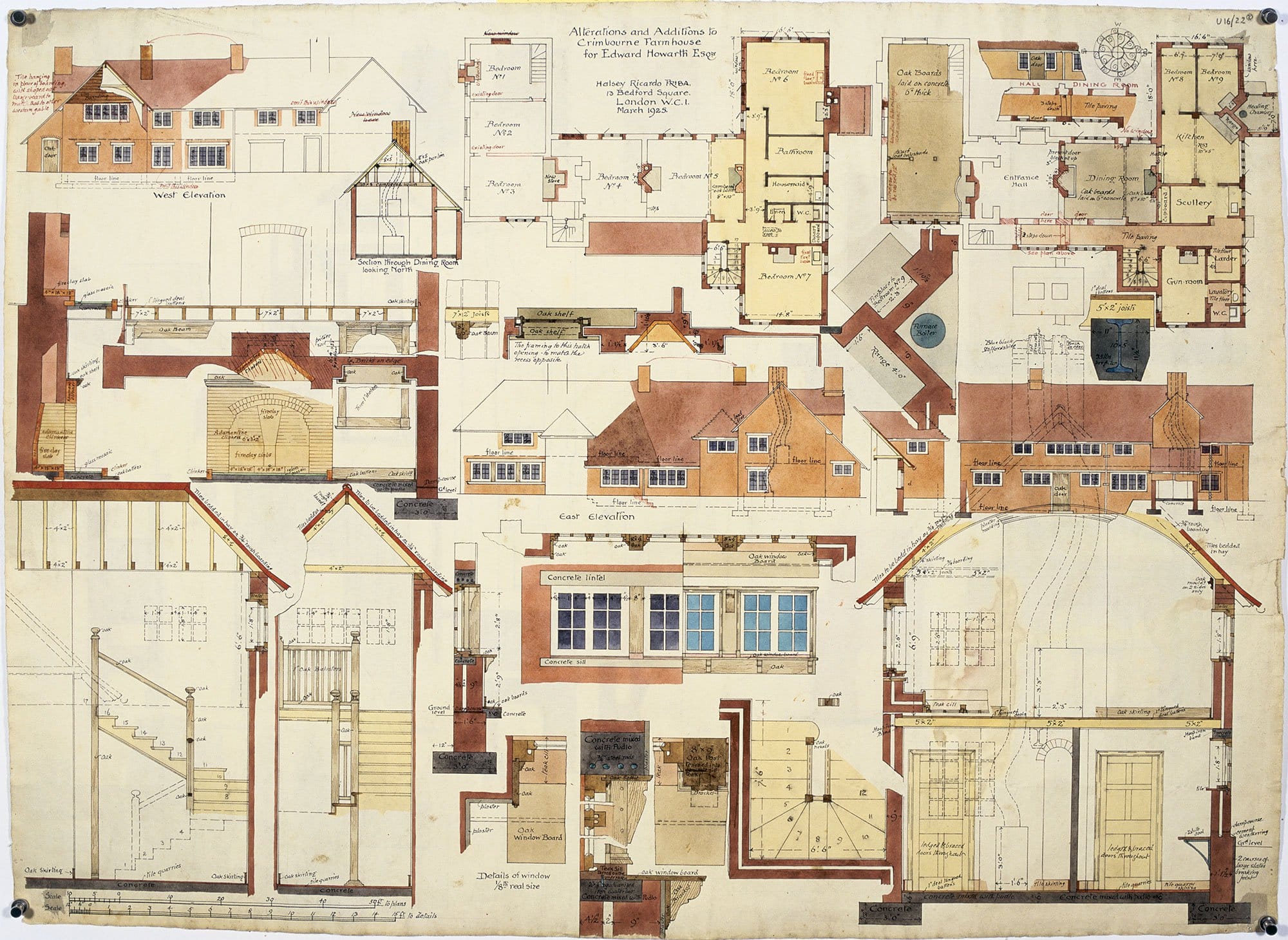

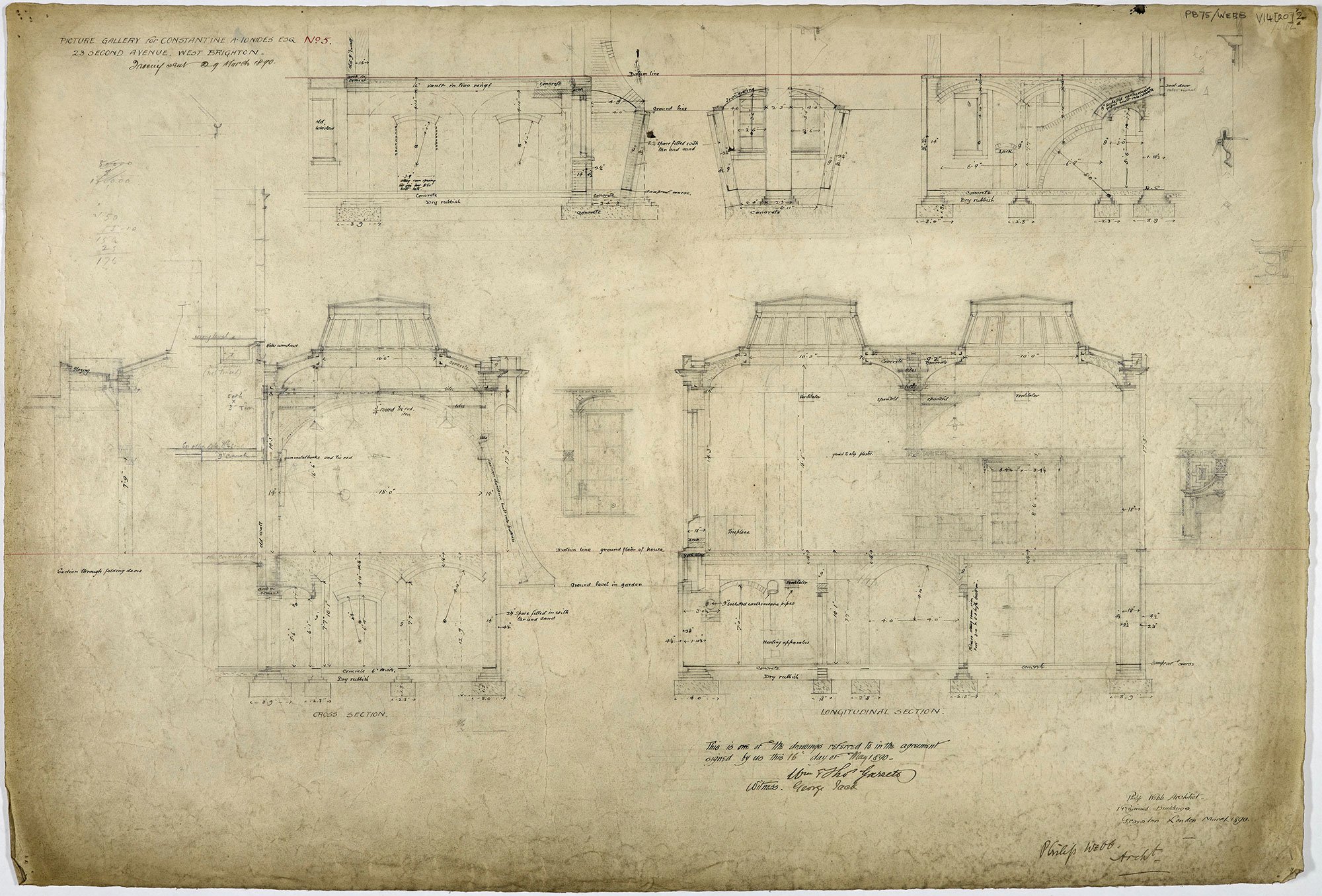

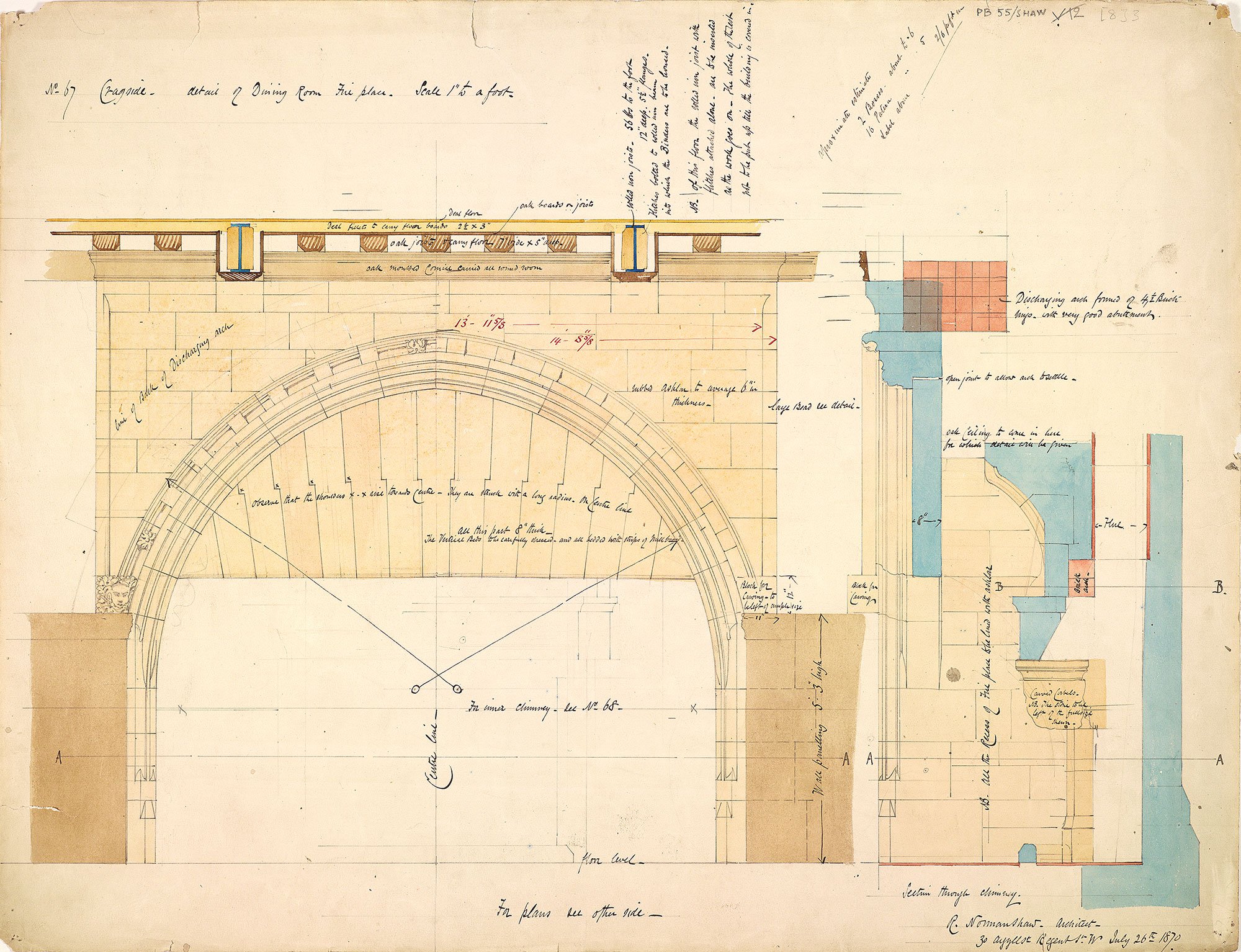

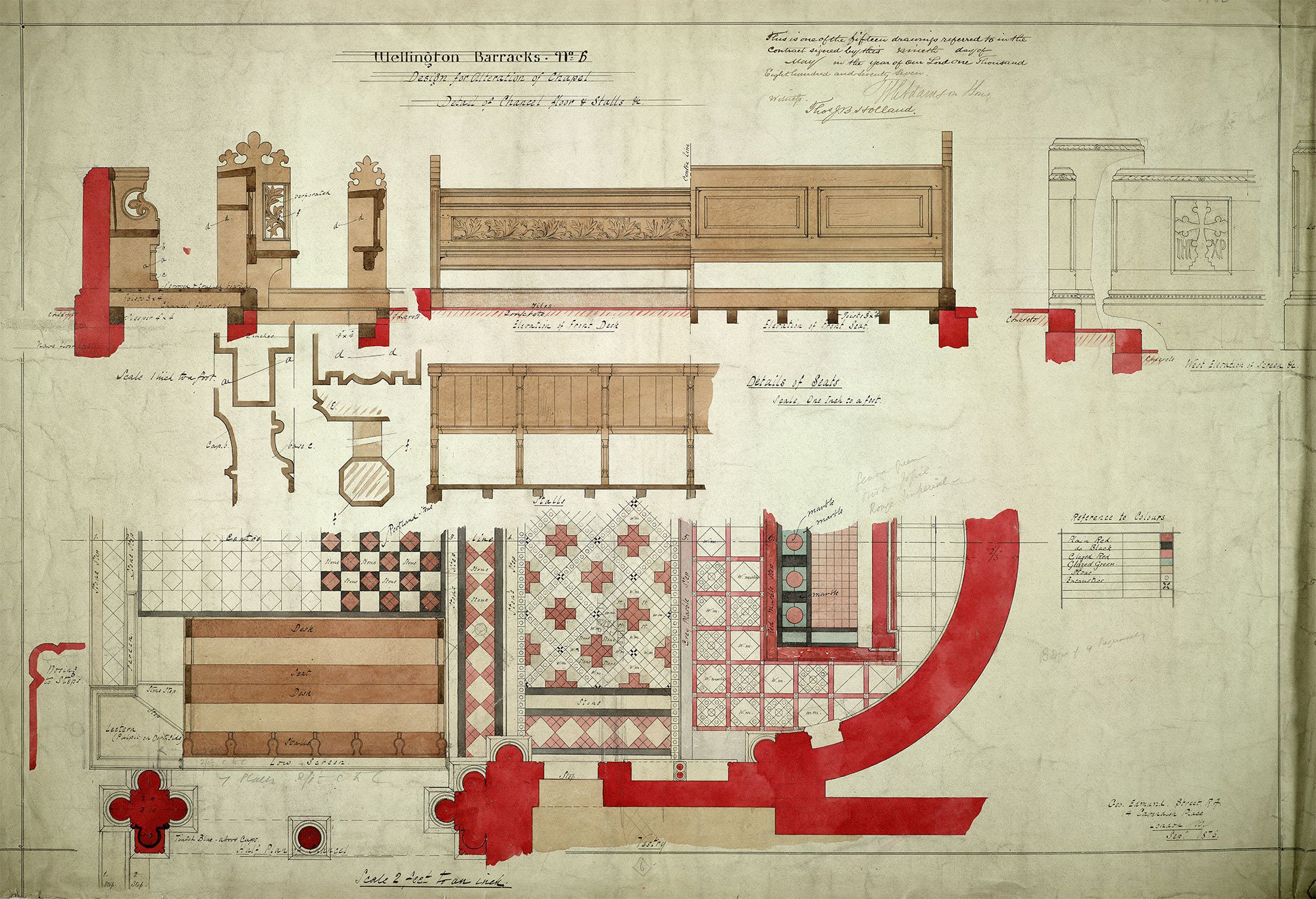

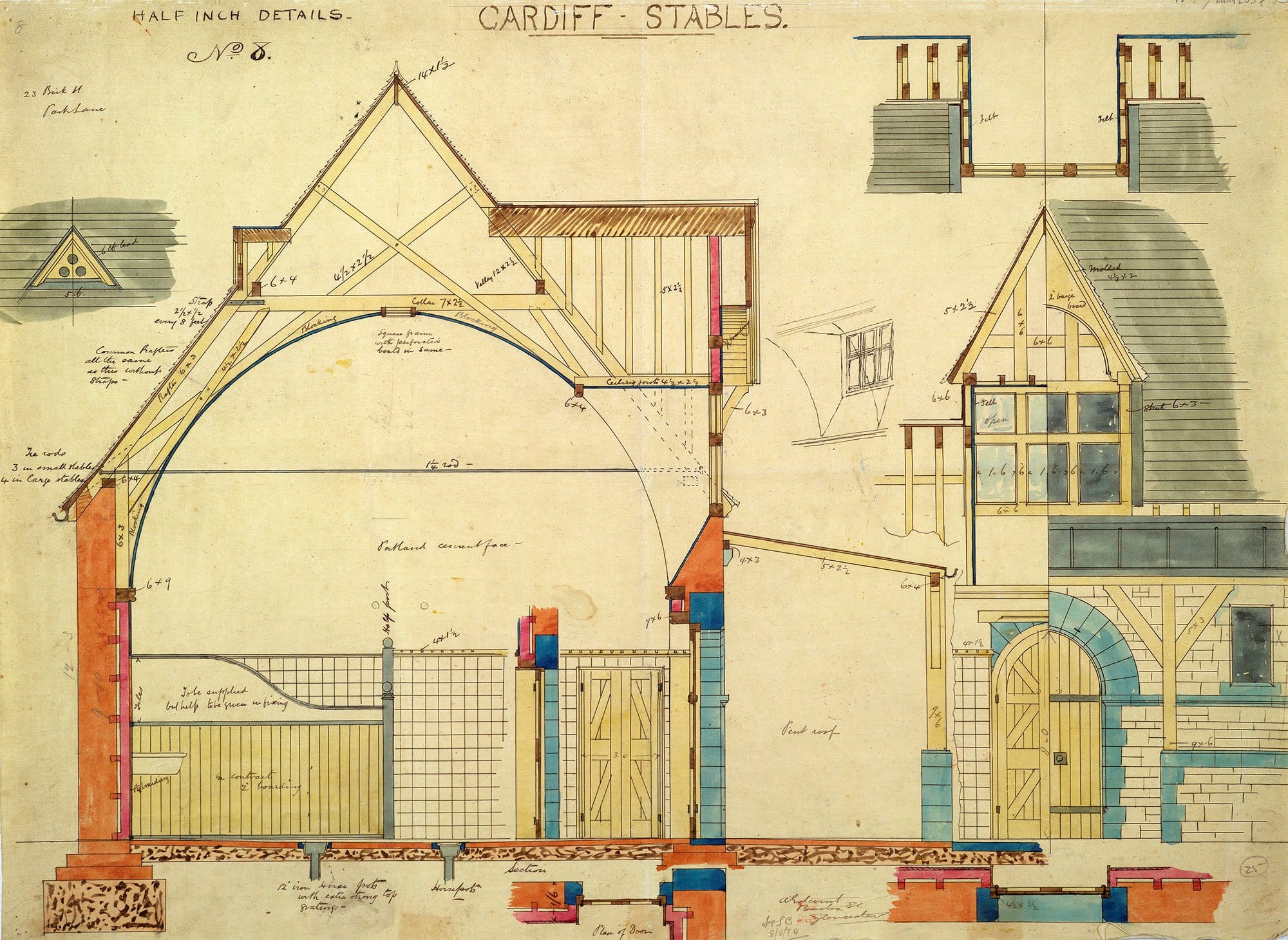

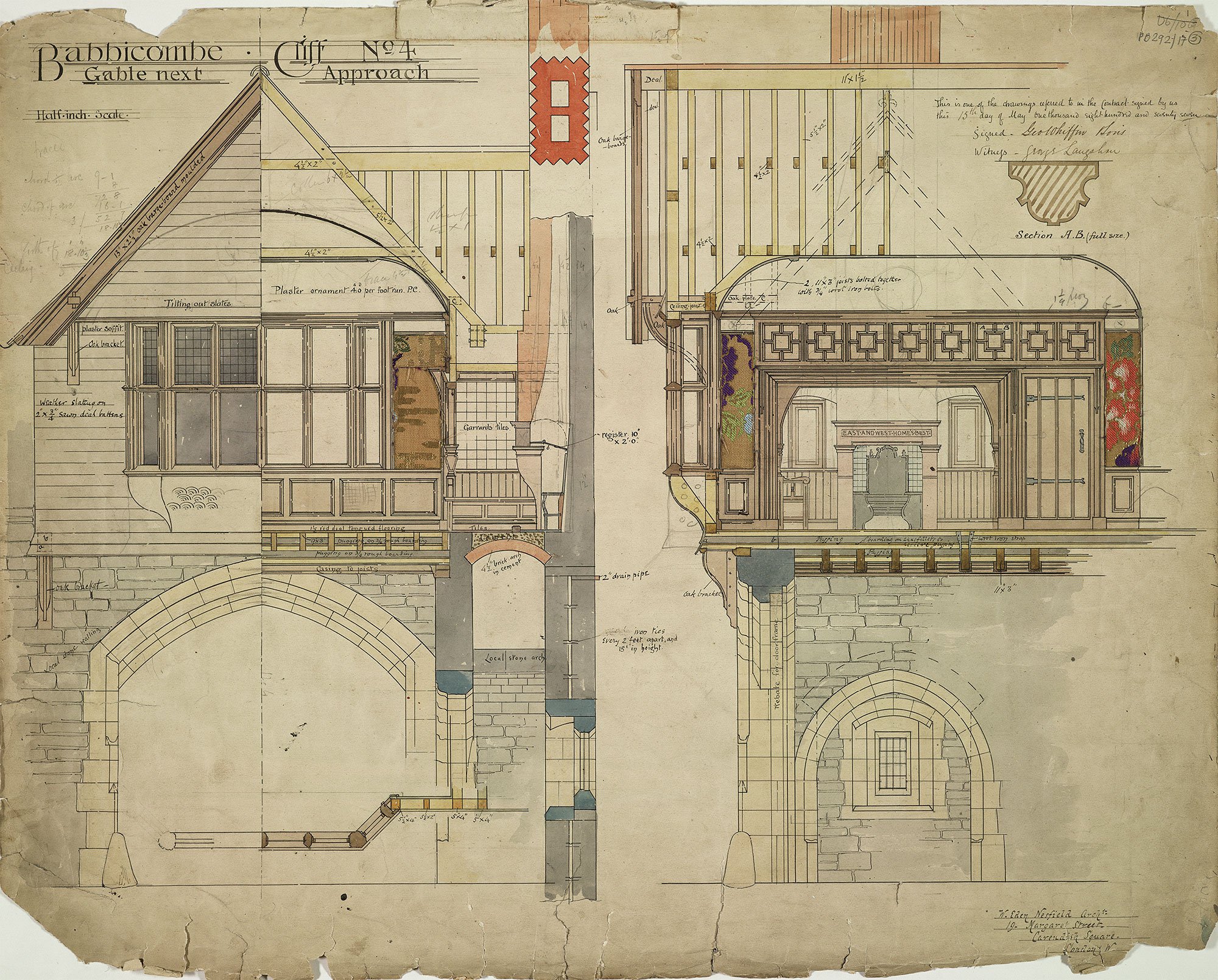

Early in 1916, RIBA president Halsey Ricardo reported on an acquisition that, when added to the works of Bibiena, Palladio, Jones and Wren, would begin to build a more continuous corpus of the drawn history of architecture. [1] This was a large set of sketchbooks and project drawings ‘from a half century ago’, which he had been at great pains to solicit, by Richard Norman Shaw, George Edmund Street, William Burges, William Nesfield and Philip Webb. Ricardo displayed numerous examples along the walls of the RIBA lecture theatre. He began his talk by noting the richness of the travel notebooks, which ‘show what an immense deal of work an architect undertook in the way of record and analysis, in order to equip himself for the actual practice of architecture’. Then, turning to the drawings from those actual practices, he called attention to their very evident value as ‘working drawings – some of them the contract plans – for buildings about to be constructed’, revealing ‘the means taken by the designer to get his visions carried into actuality, … the process of conception, the insistence on modifications, expansions, and retrenchments of the original scheme.’

But Ricardo also urged his listeners to think ‘beyond these considerations of what I would term their face value’, and to recognise that this ‘collection of architects’ drawings, for the builders’ use, forms an important contribution … to the social history of England’:

‘There is no other such impartial and unimpeachable testimony to the state of social life in the past as the changing characteristics in contemporary … Architecture. Annals, histories, pictures of the times, are all suspect, are tinged by the inevitable bias in the writers’ minds: we see the conditions through others’ eyes, not the conditions themselves…. But buildings embody the spirit of the times simply and frankly, without any question of party or political theory. They exhibit the mode of life as accepted at that time, the requirements of life, the social ideal, and also the status of the building crafts at any particular time. Consider how the passions of the last hundred years…the growth of Dissent, the Corn Laws, the Reform Bill, the Tractarian Movement, the Education Act, and so forth, have been embodied in brick and stone for the historian to mark and appraise. The value of such evidence is that it is unassailable.

‘Every age, every generation even, has its own methods of reaching actuality through the medium of plans and details presented on paper: these drawings have a pathetic eloquence to those who can hear them. The disappearance of the workman as a creative ingredient in the art of building; the individual handling of the material by the worker, obliterated or neglected; the varying standards of finish; the intrusion of machine-worked and machine-made products; these voices from the gathered papers – free beyond all question from any propagandist desire or attempt to touch other than the immediate problems before them – give to the student of political and social economy data far more trustworthy than any other papers extant…There, … the student … can compare the methods of the past masters with his own; construct his picture of England in the last and past centuries; … each digging in this quarry for his own special vein of ore.’

Notes

- RIBA Journal, third series, vol 23, February 1916, 129.

– Lok-Kan Chau