W. R. Lethaby: The Builder’s Art and the Craftsman

This is the second text in this series, where Hugh Strange visits key texts throughout W. R. Lethaby’s life.

Dissatisfied with his first book, Architecture, Mysticism and Myth, a year later William Lethaby indicated a significant shift in thinking with the essay, ‘The Builder’s Art and the Craftsman’. The text appeared in a collection of thirteen essays – including contributions from Norman Shaw, Ernest Newton and Edward Prior – that argued against formal registration within the architectural profession. An architect’s training had previously been through pupillage within a practice, but this was changing and becoming more structured in the nineteenth century, first with the establishment of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1834 and the Architectural Association as a night school in 1847, and later with the introduction of obligatory examinations to qualify for Associateship of the RIBA in 1882. Following an unsuccessful passage through Parliament in 1889, a Bill advocating formal registration was brought back before the house in 1891. Often seen as a move to protect the professional and social status of the architect, the push toward formal registration revealed a split within the architectural community. With both Norman Shaw and Thomas Graham Jackson as signatories, a group letter to the Times newspaper had galvanized support amongst those against the Bill, and this was shortly followed in 1892 by the publication of the collection of essays, edited by Shaw and Jackson, that further bolstered the objectors’ cause.

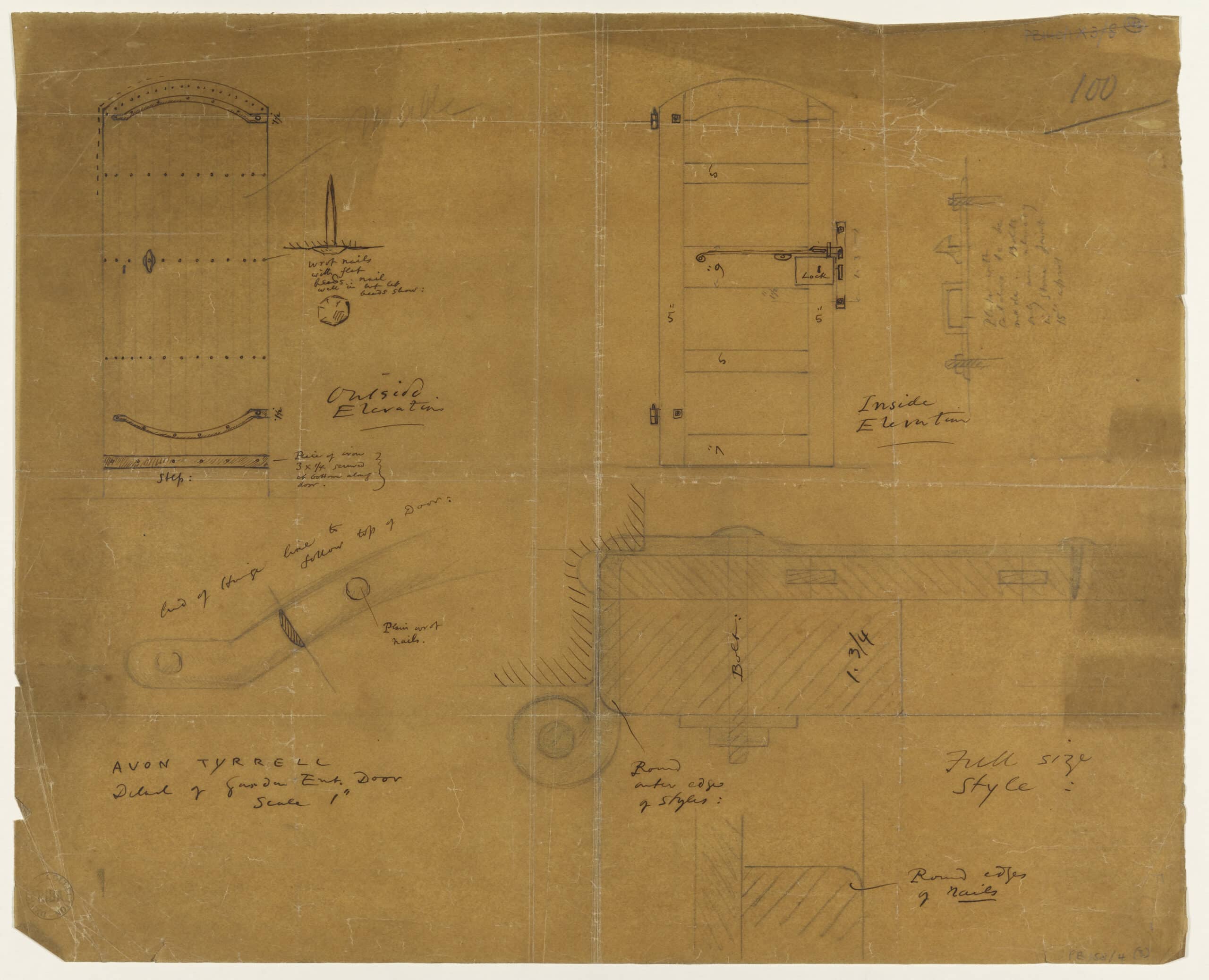

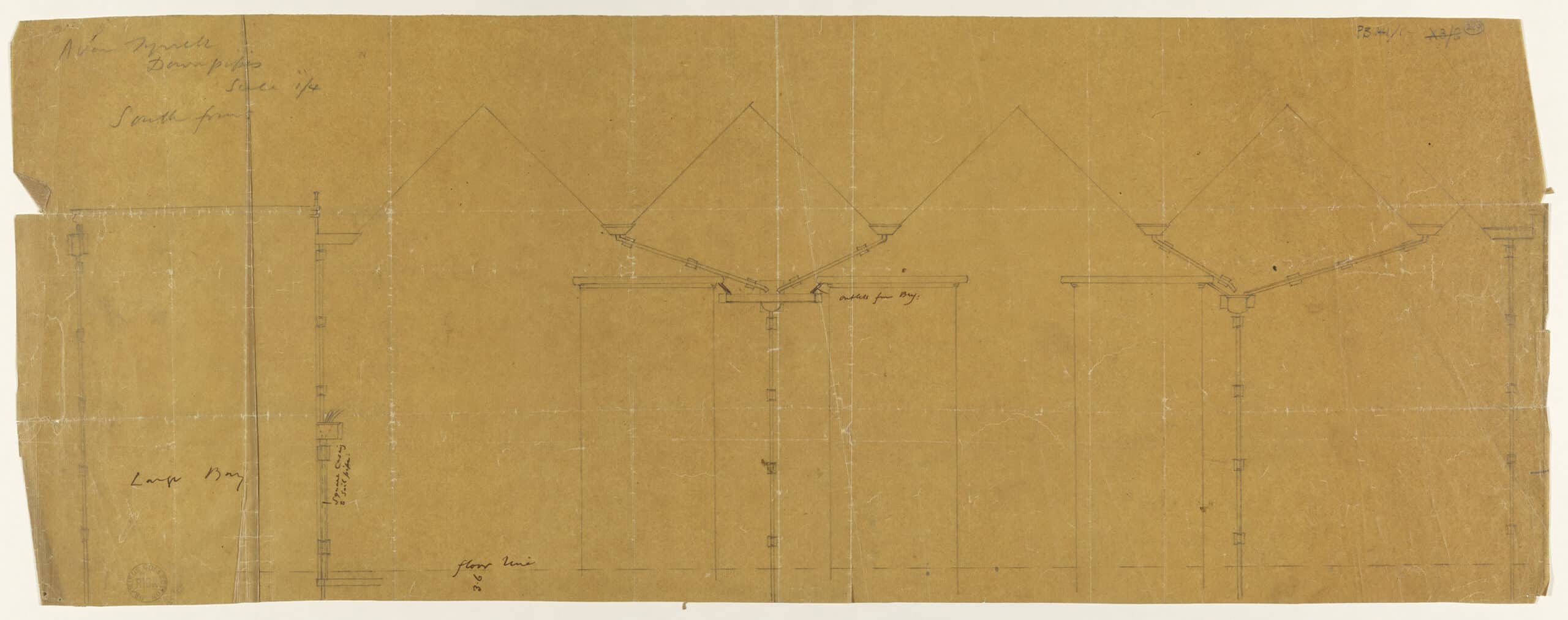

In his contribution, Lethaby laments the state of architecture at the time, suggesting his contemporaries merely practiced the academic and desk-bound re-configuration of known historic features. He considers the cause for this reduced idea of architecture to be the separation in the building of design and workmanship. Quoting John Ruskin extensively, Lethaby’s argument sits clearly within the Ruskinian tradition of thought, with its emphasis on both the relationship of architecture to its production and on the detrimental effects of the division of labour in construction. Lethaby argues that this separation, in large part a result of the Industrial Revolution, was harmful to the crafts, which he refers to as ‘the arts of building’, discussing in detail the decline of masonry, thatch roofing, plumbing and plastering. The refinement gained from long-developed traditions was no longer fully utilised, and through lack of use, the crafts were inevitably withering. Yet this concern for the degradation of craft was by no means backward-looking; Lethaby instead seeing craft as the continuing basis for an ever-developing constructive art, referring in the text to architecture as, ‘the easy and expressive handling of materials in masterly experimental building’.

But Lethaby also suggests that this separation of design and workmanship was problematic for the architect’s role; ‘The separation of the two necessarily makes design doctrinaire – a hot-pressed-paper-craft – and workmanship servile; degrading even in the ordinary necessities of building; destructive to ornamentation; a mere insult and pretence of art at which sculptors and painters do well to make a mock.’ Divorced from the actual work of construction on site, the architect, Lethaby suggests, inevitably lost a proper sense for the right handling of material.

Against this malaise, Lethaby presents a vision of architecture much indebted to William Morris, and quotes at length from Morris’s recent lecture, ‘The Influence of Building Materials Upon Architecture’, published as a text a few months before Shaw and Jackson’s collection. Positioning himself in opposition to what he variously describes as ‘office architects’, the ‘business-architect’, or the ‘building-lawyer’, Lethaby draws attention to the necessity of an architect’s direct and personal contact with construction. What is required, he proposes, is a close acquaintance with the material of building, not an arms-length involvement, such that the architect’s role might be better described as ‘artist in building’, or ‘chief workman’.

Though written almost four decades after Ruskin’s The Stones of Venice, the text acts as a continuation of Ruskin’s ideas, channelled and developed while influenced by William Morris. Lethaby went on to explore how these ideas might be practicably applicable, first within his own practice, and then later in his life as an educator. The essay collection’s authors were for the time being successful, and the Parliamentary Bill against which the texts were directed did not pass. Indeed, it was not until many years later, in 1931, that a Bill was eventually passed and a register of Architects established.

‘The Builder’s Art and the Craftsman’ was published in Architecture a Profession Or an Art: Thirteen Short Essays on the Qualifications and Training of Architects, edited by R. N. Shaw and T. G. Jackson (London: John Murray, 1892). You can read this online here.

Notes

This text supplied the title for Hugh Strange’s recently published essay in AA Files 77 that describes the evolution of Lethaby’s approach to construction, ‘The Craftsmen’s Drama’.

– Hugh Strange