Notes on the 2020 Summer School: Encounters in landscape

The notion of the countryside as a space for radical transformation, a messy intersection of heterogeneity far removed from the homogenising forces of the city centre, makes it the perfect territory for experimentation.

As a landscape where change is the only context, Shatwell Farm is the ideal setting for an Architecture Summer School; the perfect backdrop for testing, making, absorbing and releasing knowledge through shared learning amongst a tight knit group of students. The perfect incubator for understanding what first year in architecture school is all about.

As one of three tutors on the 2020 summer school, our programme oscillated over the course of a week between the pragmatic and the poetic. Memory mapping exercises at the Hauser & Wirth gallery taught us the power of the imagination and survey as the first act of design: that is, designating or deciding what is important to include in a map and what isn’t. This exercise was preceded by days of sketching in the town of Bruton, and punctuated by visits to the galleries and their associated courtyards. Together, these activities helped the students articulate and release a flow of thoughts through loose sketching; slowly beginning to learn a way of thinking in order to approach the bigger task of designing a pavilion at the farm.

Arriving here, the students were called to draw on personal moments of encounter with buildings that resonated with them from childhood. The aim was to highlight that latent experiences, brought out through imagination, remain our essential catalyst for beginning. Through sketching the landscape and drawing on the memory of early encounters, the students’ personal experiences are validated and given a platform for further exploration, along with getting them to draw on personal experience and cultural contexts as a motive for design. The learning experience is one of unearthing deeper thoughts and influences rather than one of filling the students’ minds with pre-mediated, textbook ideas. An experience of learning by doing.

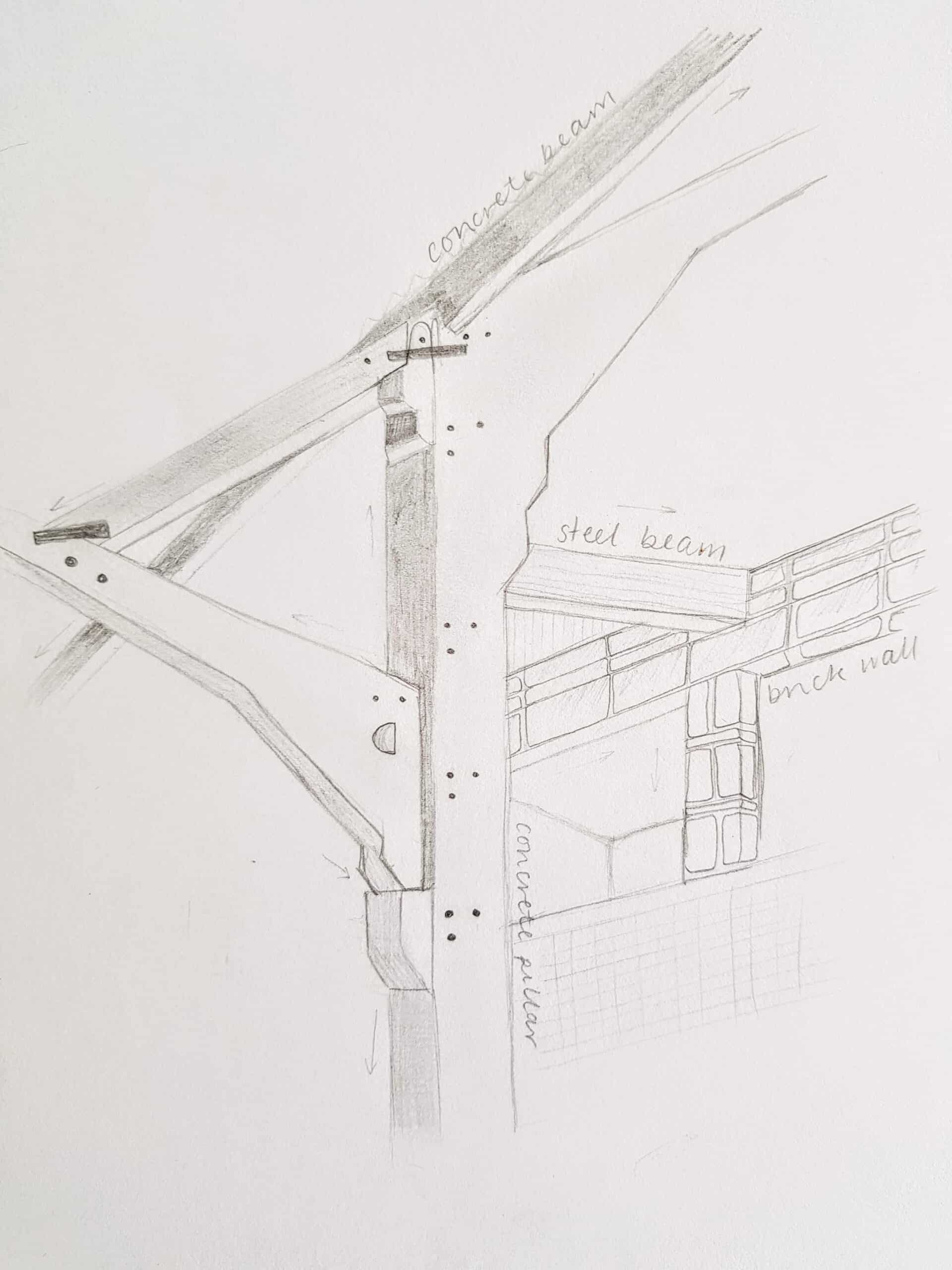

Turning our gaze from this idealised, painterly landscape of the imagination to a productive one, we set out in search of farmyard tools and offcuts that could be appropriated. This meant turning our attention to the utilitarian and performative aspects of design, as well as having philosophical conversations around the effects of what a new addition might do and the agency it might have on the farm. Grappling with the metrics of measure and tolerance, we started thinking about new and old and how to translate these seemingly abstract ideas into a built form.

We also worked to recognise the multifunctional and adaptive ways of the vernacular forms we found around us, observing these for clues.

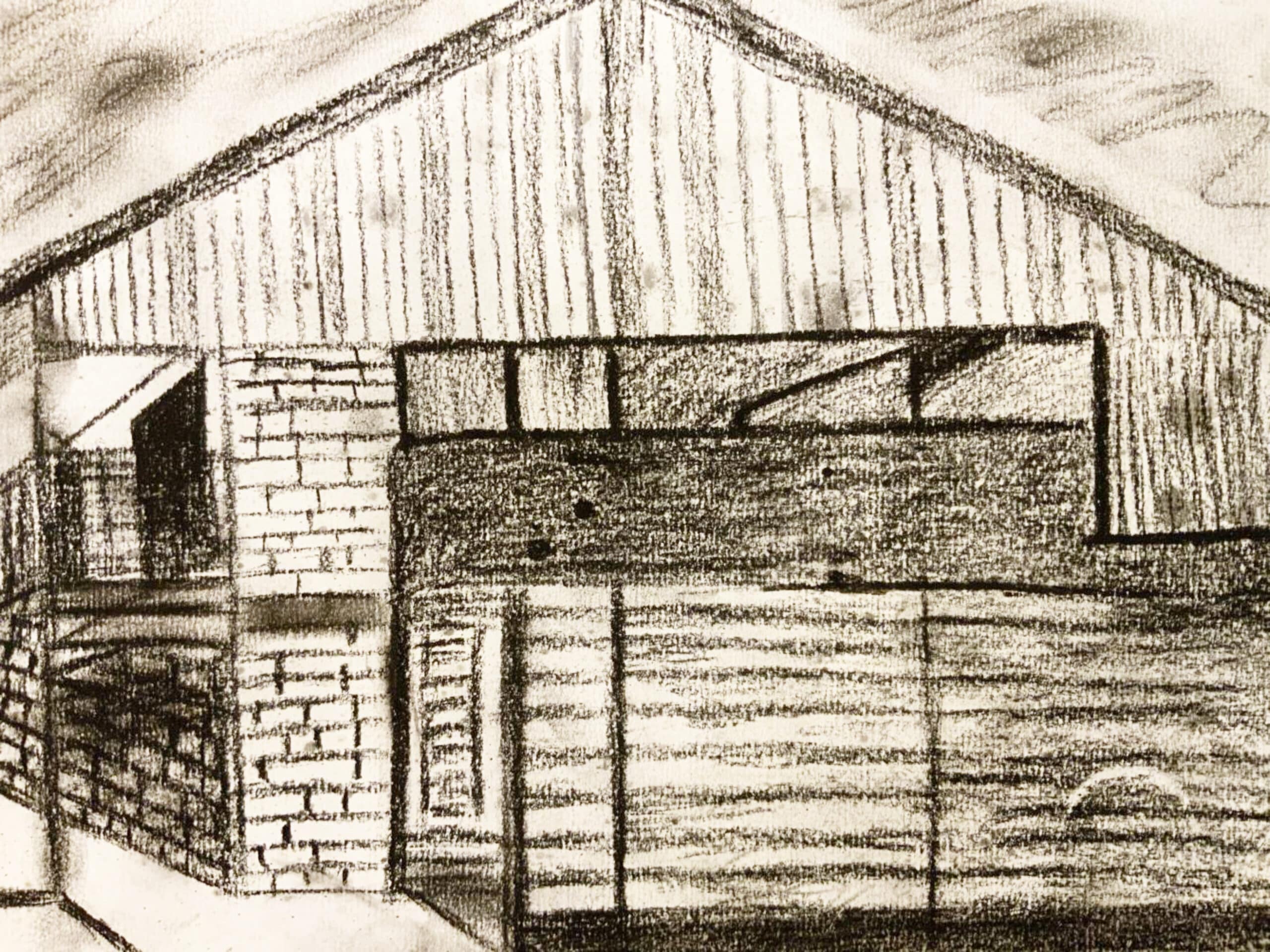

Working in a language of farmyard vernacular, with Stephen Taylor’s Haybarn and Hugh Strange’s Drawing Matter Archive and silo library conversion as sources of built inspiration, we came to understand architecture and the vernacular not simply as an aesthetic but as a way of doing; a material expression of our relationship to the land and a process we were actively mimicking on site. Although time appeared slow and constant, conditions seemed to be ever changing. There was a sense of urgency, of making do and getting by where our programme was constantly at the mercy of the elements and our responsiveness never too quick.

Ideas of collectivity and gathering began to immerge, as they commonly do when working in a vast, open landscape – more likely born out of the immediate and repetitive need to seek sudden shelter from a downpour of rain. These gave rise to a tensile-draped structure being proposed by one group of students, making reference to primitive ideas of marking territory and seeking protection from the elements within the vast floor plane of Clancy Moore’s unfinished Atcost building.

Meanwhile, a group downstairs was concerned with level access and creating an intimate point of arrival. They worked hard, making use of every object that can be shaped, moulded or draped to create forms such as the adaptation to an uneven terrain by the creation of a wired ramp, strategic use of vegetation for shelter and enclosure, resourceful use of topography for drainage, and the creation of elaborate architraves to give scale and composition to large, unfinished structural openings. These made reference to the many doorways and passages we had sketched in Bruton earlier in the week.

The final exhibition illustrated this process of finding a ‘place-conscious poetics through elements derived indirectly from the peculiarities of a particular place’ as Kenneth Frampton once wrote. The translation of poetic imaginings into realised built additions, which so often happens when landscape transcends itself from being an idyllic image to a productive, working territory, came to fruition as the students were invited to display their sketchbooks and large format drawings for visiting family and friends.

In landscape, everything is transformation yet equally subject to the passage of time. With regard to this, the impact of the past year on levelling access to the field of architectural learning and drawing has not gone unnoticed. This year’s summer school will be a blended hybrid of physical and digital participation, levelling geographical inequities and improving access to a profession in urgent need of structural and pedagogical reform.