68½ degrees, Sverre Fehn and the Nordic Pavilion: Review & Excerpt

Review

By preserving the trees on the site within his pavilion in the Giardini, Sverre Fehn offered Venice an insight into a unique Nordic sensitivity towards nature and the environment. He tempered the harsh Mediterranean sun to evoke the horizontal light of the Baltic through a spectacularly innovative technical design for the roof; its rigour matches the pure white space for art that he created, itself radical in both immanence and flexibility. That the building had come to exist at all is a triumph of first-growth Nordic social democracy in its five different national iterations, brought together in an important parable about post-war regional entente.

These stories of nature, light and democracy form a compound mythology. Each intriguing figment reinforces another, until the momentum of the narrative is beyond challenge, to the point where every word of the preceding paragraph can be proved quite untrue.

That proof tumbles, page after page, out of Mari Lending and Erik Langdalen’s wonderful study of the diverse archival sources on the building and maintenance of the Nordic Pavilion, which they and their students have been inventively piecing together over several years. The authors maintain that they are driven by a rigorous impartiality, and a reluctance to intervene with subjective judgement, in line with their ambition, at some future Biennale, to curate an exhibition about the pavilion, within it. In practice, their—nordic?—curatorial neutrality might as easily be seen as a very clever literary judgement; as they unfold the story to us through partially redacted meeting minutes, drawings, photographs, frenzied correspondence, arguments about funding, and endless crises in the planning and construction processes, commentary becomes superfluous, and the result is sharper (and, perhaps, far funnier) without it.

On the trees: we find out that they had to remain because of the Venetians, and not out of any nascent Nordic respect for site or for the environment. The large footprint demanded by the programme, which was conceived as a simultaneous display by each of the three commissioning countries (in the end Sweden, Norway and Finland), required confrontation with the local bureaucracy charged with protecting the Giardini, for there were few enough trees in Venice (and these—all undistinguished, non-native, and mixed species—were growing against the slope of the only hill in town, formed from the rubble of the original Campanile, after it collapsed in 1902). In the end, most of them were dead within a couple of years of completion, their roots compressed and inadequately watered. Even the building’s most famous gesture—the girder divided at the south west corner to accommodate the great plane tree on the alleé, came late in the scheme after it emerged that it had been wrongly plotted by the Venetians on the original competition survey.

On the roof: the weather comes in just where the structure needs to be most robust, where the upper grid of impossibly narrow and metre-deep beams carries the structure across the openings required for the individual tree trunks. The fibre glass covering continuously deteriorates and discolours and has been replaced numerous times through the life of the building.

On the space itself: generations of curators, starting with Pontus Hultén himself at the opening exhibition, have had to weave and dodge around the architecture, contending with the weakness and vulnerability of the beams and walls as a support for a hanging system, and the resistance of the interior to convenient or convincing subdivisions. Hultén was reduced to installing a mobile sculpture on those dangerous steps as a barricade; and, as the Norwegian curator put it in 1995, somehow Fehn ‘still dictates the selection of artists’. The stylobate form of the covered space, sixty-five centimetres above the venetian mud, was lost as the plans developed, most likely in response to the instability of the made-up terrain, which intrudes itself again and again into the design and construction process. Even the glorious whiteness of the ‘cube’ was an accidental retrofit; the black Norwegian granite floor, impossible to keep in place, and defaced by the grit from visitors’ feet, was gone within six years of completion—replaced by the white marble from Trani known to most of us.

As for the politics, much of the impetus for a collaborative pavilion came first from the Biennale directorate, with a frugal eye to space and towards combining the site with the adjacent Danish pavilion. In the years after 1945, the long shadow of Gustavus Adolphus and, perhaps, of Swedish neutrality, still hung heavy over the first moves of the Nordic Council. In the event, the Danes recused themselves early on, their cooperation blocked by the New Carlsberg Foundation, who had paid for their pavilion in the 1930s. Iceland expressed little interest, and the Finns were detached and distracted by the uncertain fate of their existing small pavilion by Alvar Aalto. It fell largely to the Swedes to convene an Inquest Committee, meeting in their Ministry of Ecclesiastical Affairs, to make the project happen; the real heroes of the story are the bureaucrats who shepherded it slowly onward. None of this was much helped by the competing interests of the various national embassies in Italy, nor that French was the diplomatic language of communication between Italy and the Baltic.

For all of these histories, the job of making judgements is elegantly outsourced by the authors to an array of scholars, engineers and curators in a fascinating collection of short essays at the back of the book, in which they recount their own interactions with the history, aspiration, reception, maintenance, and the uses, of the Pavilion. Amongst these, the last word goes to the late Fredrik Fogh, the Danish site-architect, based in Milan, who heroically supervised both construction, and maintenance in the early years. Interviewed aged 94, he commented that ‘so heavy a roof on a site of mud… I have always been in doubt whether it was not “to shoot sparrows with a cannon” (as we say in Danish).’

As I read, lots of fruitful questions came to mind:

About Fehn himself: was the famous holy innocence, and all the poetic diction, a mask donned to navigate the politics, whilst preserving the rigour of a powerfully abstract formal idea, ironically free of any of the nationalist interest of the other players? Certainly, in later years he grew complicit with many of the myths as they proliferated.

Do the myths even matter? I did wonder myself, last week, listening to a very thoughtful student who had incorporated some of them, innocently and usefully, into the thinking about her own project for an exhibition space.

And then: are there histories of other buildings, ones that appear to us to be equally self-assured, open to be written in the same vein and with the same forensic rigour deployed here by the Nordic team? Of San Cataldo, the Castel Vecchio, or of the Villa Mairea?

The simple moral of the story is that Nordic Pavilion is still in formation, in a process where all the players: Venice itself, the Biennale committee, the politicians and functionaries of each of the countries, visitors, and historians, have maintained very different conceptions of the life of the building, both of its cycle and span. It was built with the idea that the three countries would each exhibit side by side, in separate spaces. And with no expectation of the evening openings (that were to generate a crisis in 1970 over the discrete installation of electrics); or, of an architecture Biennale (which was to bring a whole new category of curatorial problems); let alone, of being open for six months every year to half a million visitors.

Some clue to the answers might lurk in the name itself—‘pavilion’ hints at a transience that will be forever at odds with the concept and function of Fehn’s masterpiece as they exist for everyone else. However unstable a structure and however resistant to change, the Nordic Pavilion will always demand to be returned to the ‘original’ condition and configuration, in which, as it now turns out, it had never existed. Quite certainly, it will never now be demolished.

The multiple authors of the book offer us their versions of architecture’s unending battle with time: searching backward looks, in which we see near-impossible acts of reconciliation as the condition of making great architecture- and of its survival.

To find out more about Sverre Fehn, Nordic Pavilion, Venice: Voices from the Archives by Mari Lending and Erik Langdalen, click here.

Niall Hobhouse is the Director of Drawing Matter.

Excerpt from the book

The Competition

The competition for the Nordic Pavilion was announced on June 28, 1958. The deadline for submissions was December 15, 1958. At 5 p.m., on February 18, 1959, a press release announced the result: ‘The jury fully acclaims architect Sverre Fehn’s entry, which can be characterized as a covered part of the Biennale park. The pavilion is open to the flow of visitors that passes this busy part of the exhibition ground. The pavilion’s interior consists of one single room with movable wall panels, enabling a range of different exhibitions.’ [1] In March 1958, the Swedish king had announced that Sweden would arrange the competition, and that one architect per country would be invited. [2] The MFA in Stockholm was asked to exhort the other governments to act accordingly. [3] For a year the Swedish Biennale Committee had discussed different models: to give the commission to one architect; to make a call for an open, Nordic competition; or to invite architects from the five countries or simply from one. [4] They wondered if Denmark, as part of the ‘pan-Nordic project’, would accept a Nordic competition, or if the Swedes, par courtoisie—in regard to the Danish sacrifice to ‘the Nordic idea’—should arrange an exclusively Danish competition. [5] They discussed inviting an Italian architect to sit on the jury, and decided to ask the Swedish architect Nils Ahrbom if he would serve as the chairman. [6] While the competition brief circulated for comments in the architectural associations of Norway, Finland, and Iceland, the Swedish Biennale Committee asked the Venetian lawyer Mario Vianello-Chiodo, who was fluent in French and German and worked for the Biennale, if he could answer questions about the site from the competing architects. [7] The Swedish ambassador in Rome made a formal request to Vianello-Chiodo (who often signed his letters with only Chiodo), and the lawyer was delighted to serve as the local advisor. [8] This service caused an array of correspondence on how to compensate Chiodo, and a little anthropological lesson for Nordic architects and bureaucrats on Italian culture. Chiodo had told the Swedish consul in Venice that he preferred ‘a gift’, rather than a honorarium. This ‘gift’ appears in quotation marks in numerous letters, and is even commented on in a footnote in one letter. [9] Stockholm was eager to sort out the matter, before the architects went on site visits to Venice. [10] The ambassador suggested giving him an Orrefors vase (a Swedish design classic) and perhaps some cash. [11] Half a year later, in the beginning of 1959, they discussed whether Chiodo could perhaps be granted an order, such as the Vasa Order or one from the Swedish Academy. [12] In the end, the committee prepared precisely a gift, a selection of works from Nordic artists: prints by Segerstråle and Aukusti Tuhka, and woodcuts by Stenstadvold and Knut Rumohr – the latter one of the two Norwegian artists displayed in the pavilion in 1962. [13] In June 1960, the portfolio was sent to Chiodo, with heartfelt gratitude. [14] While authoring the competition brief, Snellman and Lars Grönlund, who assited him, were unaware of the plans for expanding the Danish Pavilion, and still deliberated if the northern terrain should be part of the program. They decided that the winning architect could prepare something for that plot later on. [15] Realizing the imminent actuality of the Danish plans, they insisted that Copenhagen refrained from issuing a definite decision until after the competition. [16] Vøhtz assured Stockholm that nothing had yet been decided, that the drawings were not done, and that they had not yet negotiated with the Italians about expanding toward the west and north. [17] Yet in February 1958 Koch had already proposed two schemes to the Danish Biennale Committee. In the fall a project was approved by the City of Venice, and by January 1960 a telegram confirmed that construction could begin immediately, aiming at completion ten days before the opening of the Biennale. [18] By the time the competition brief was done, they knew that Denmark was planning a northward extension.

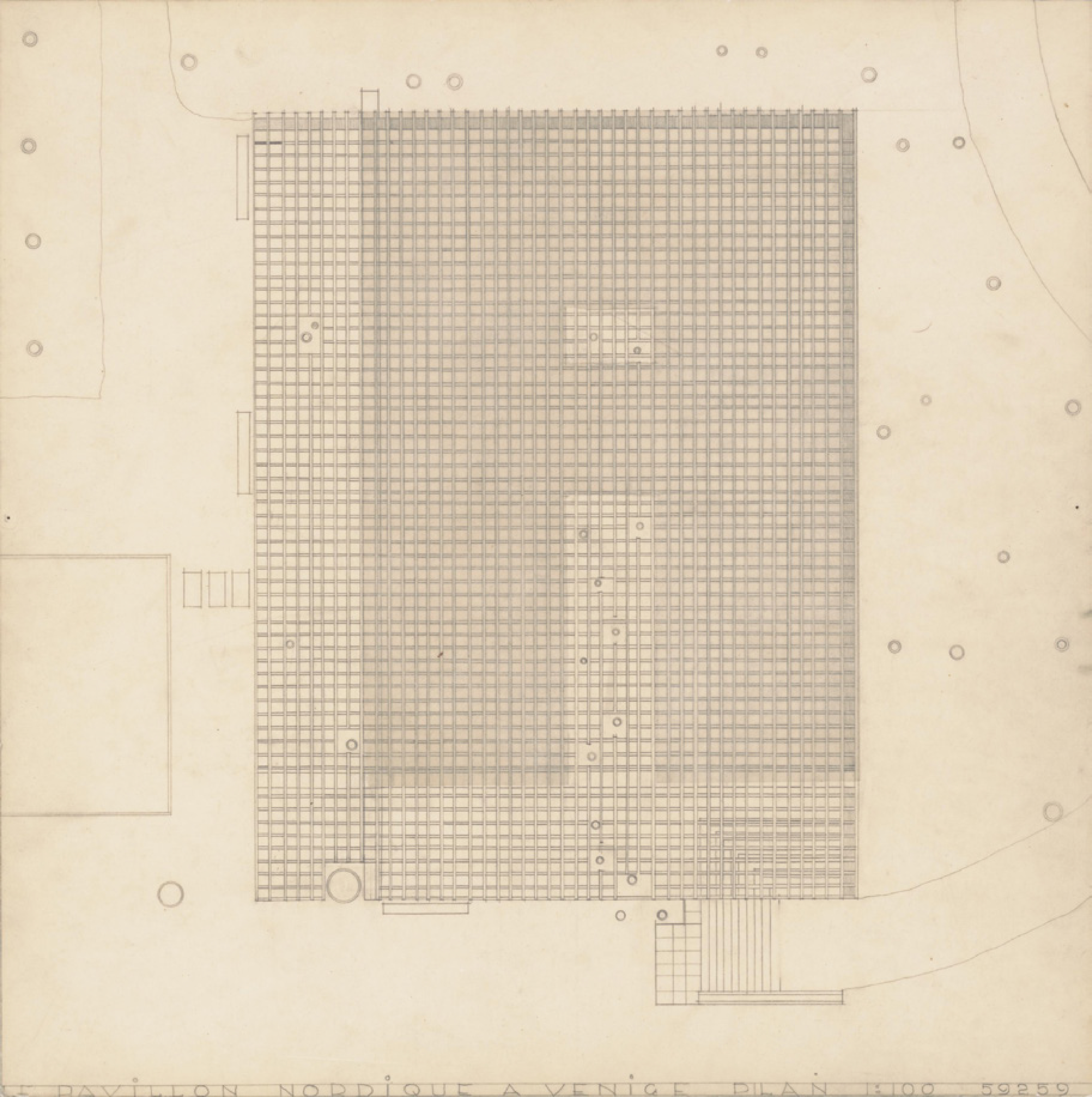

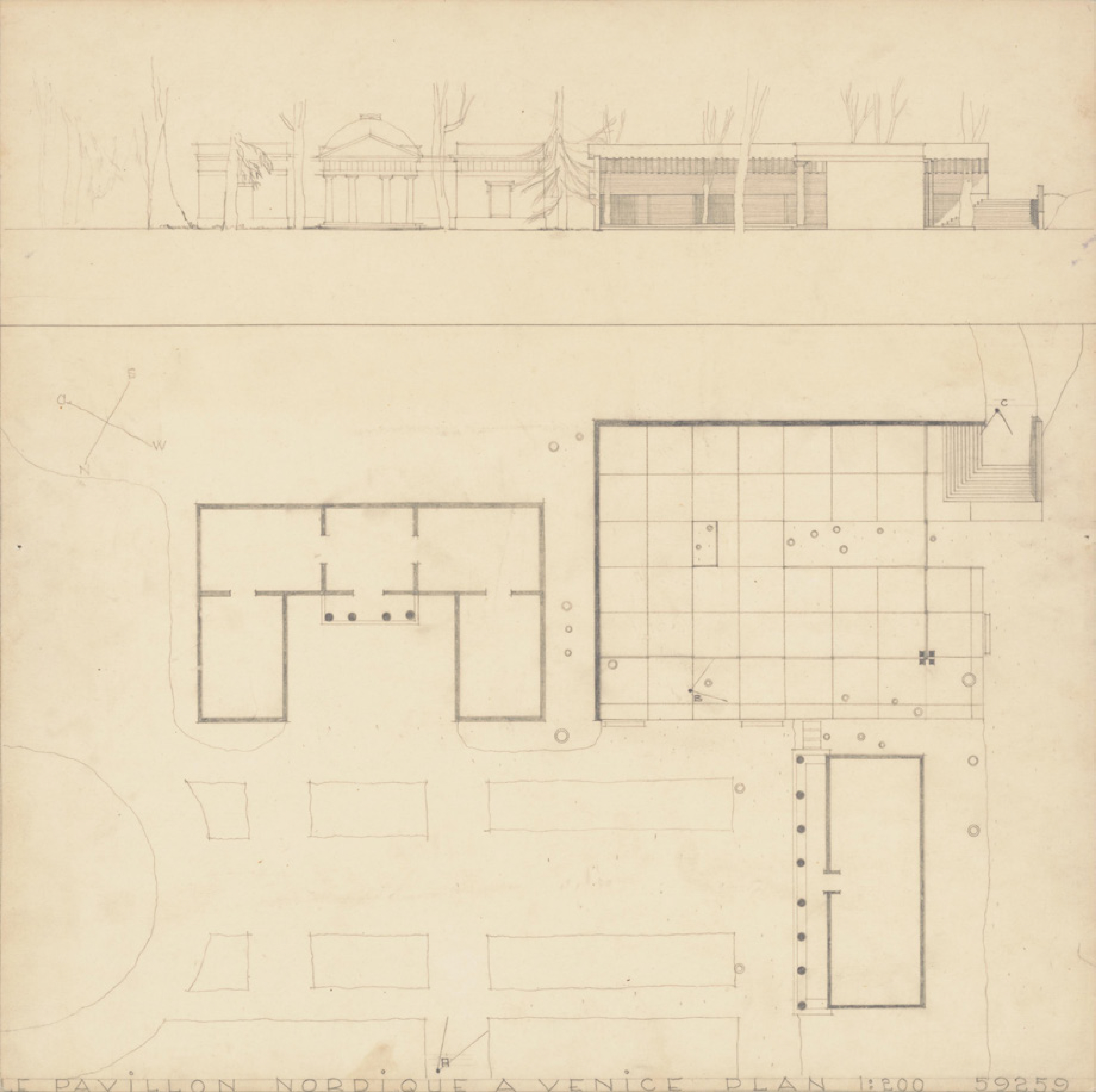

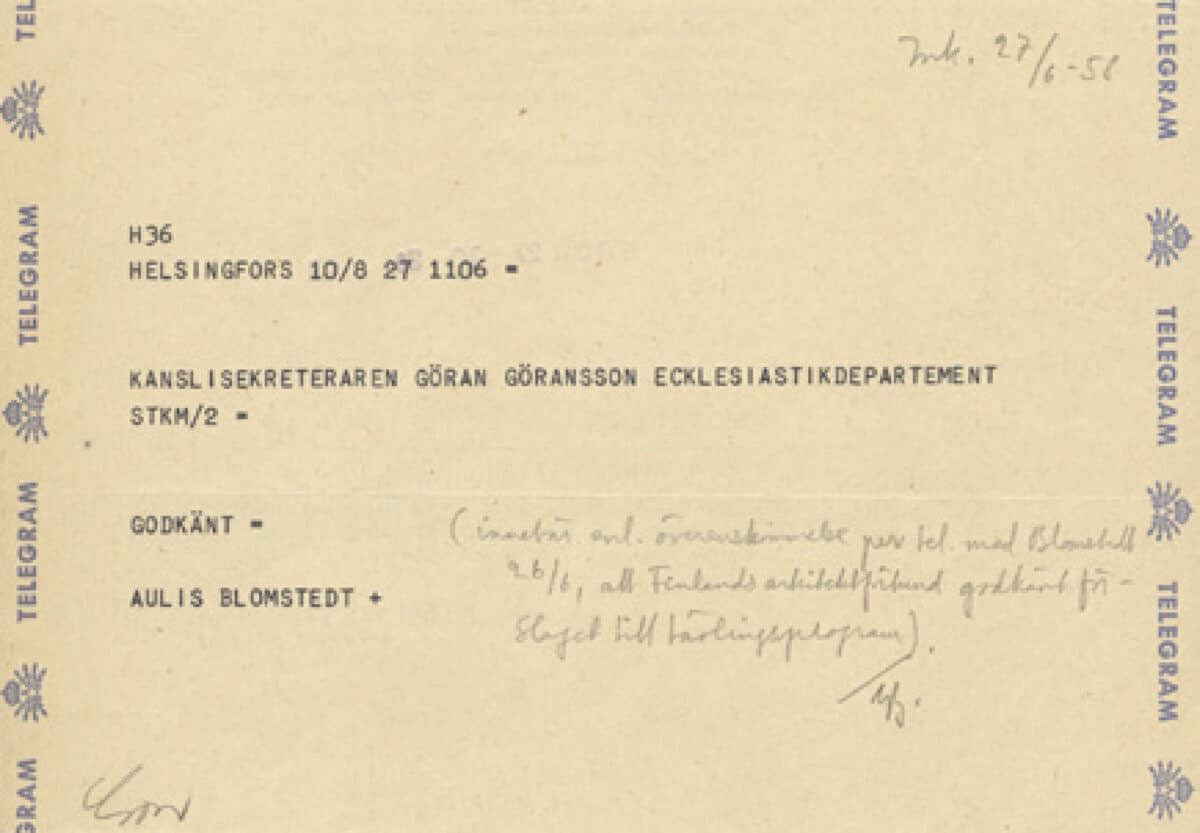

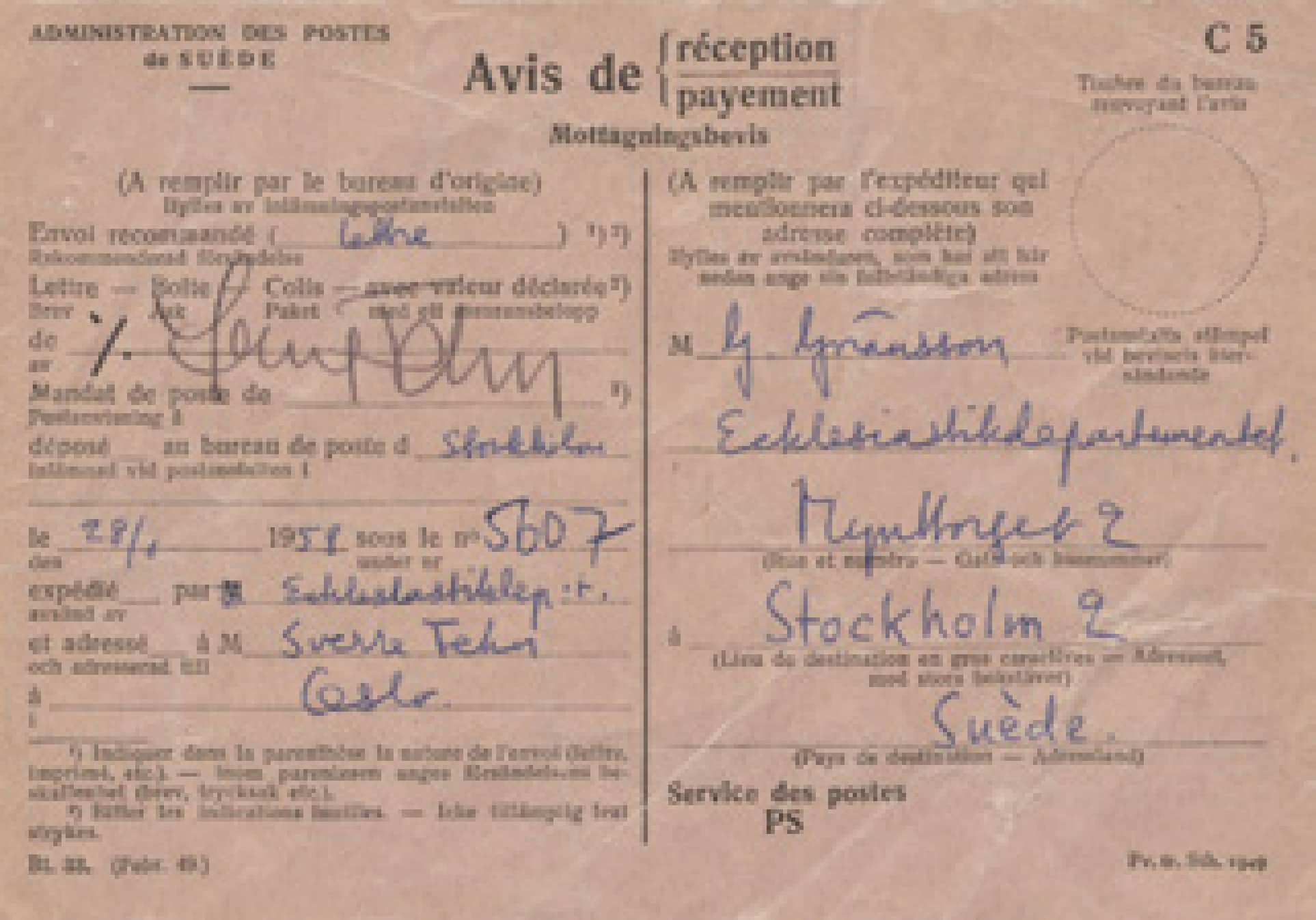

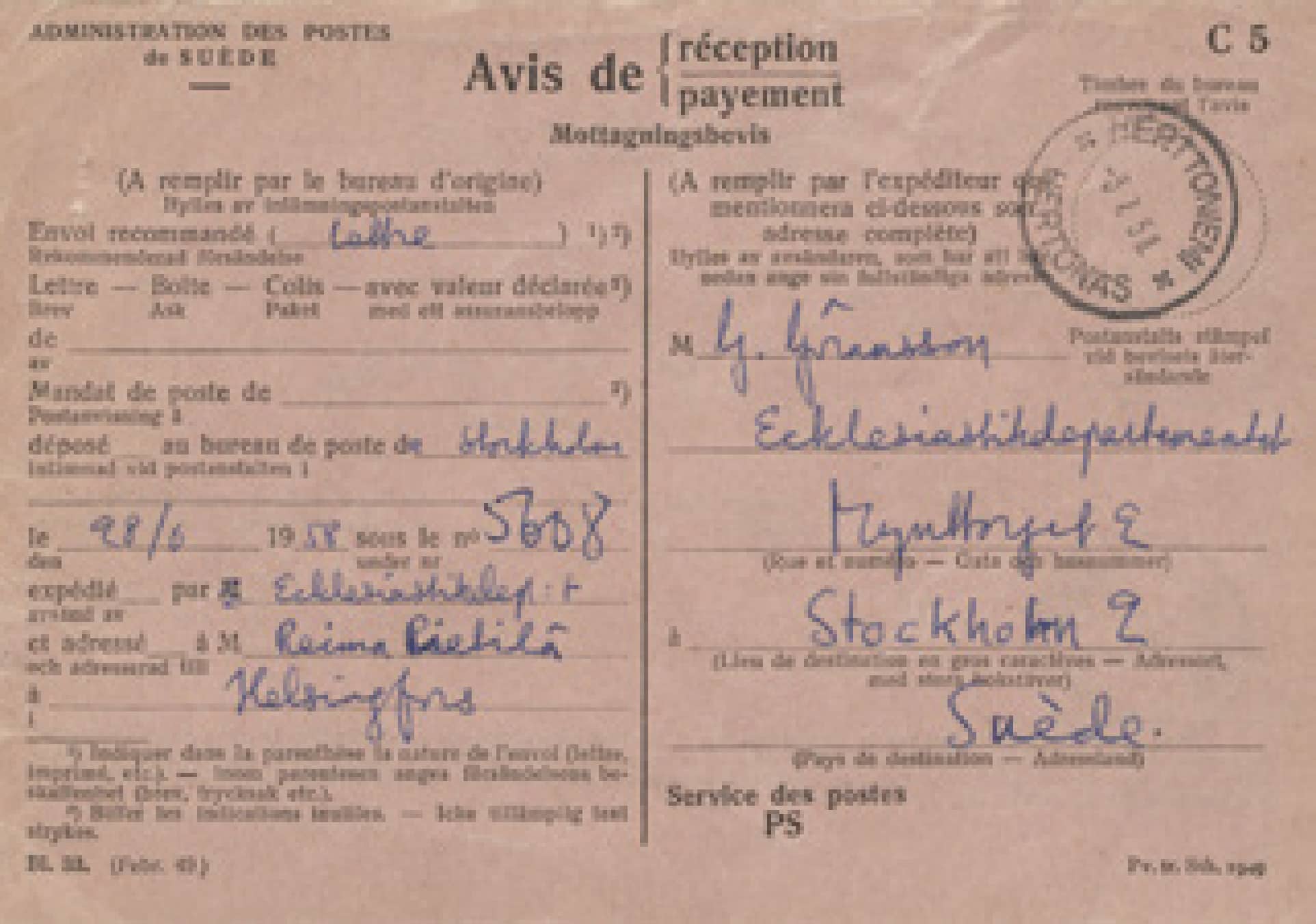

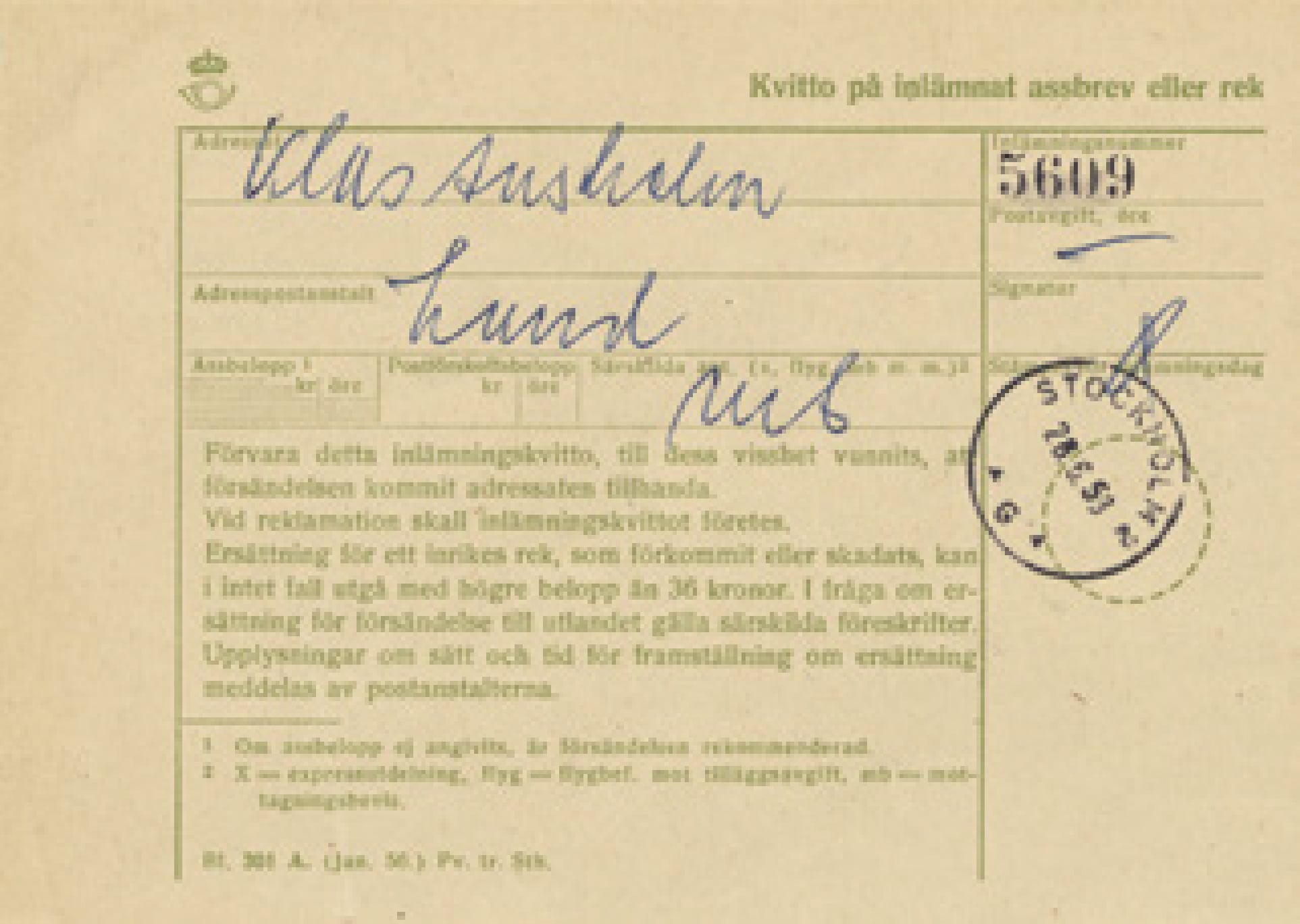

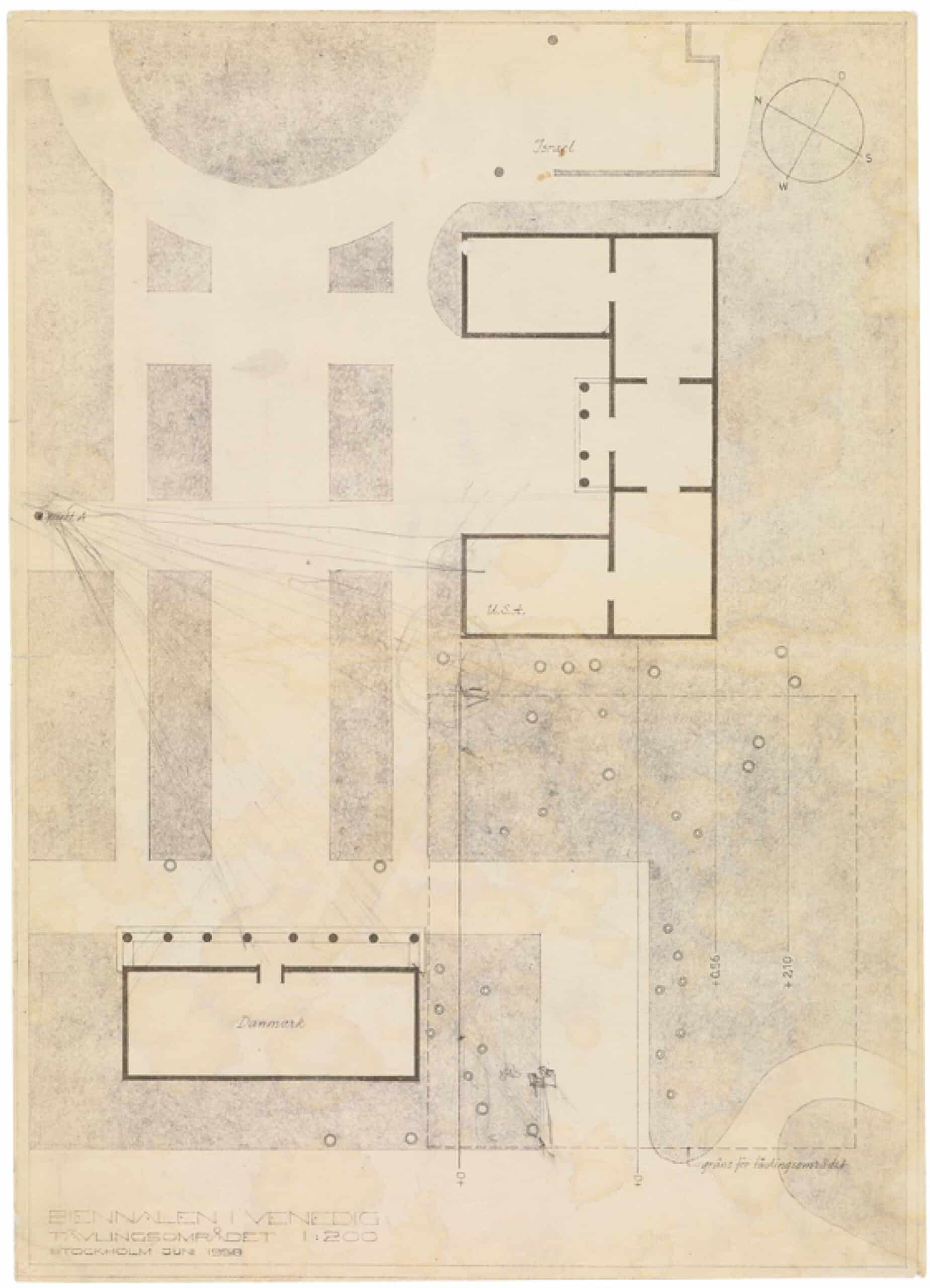

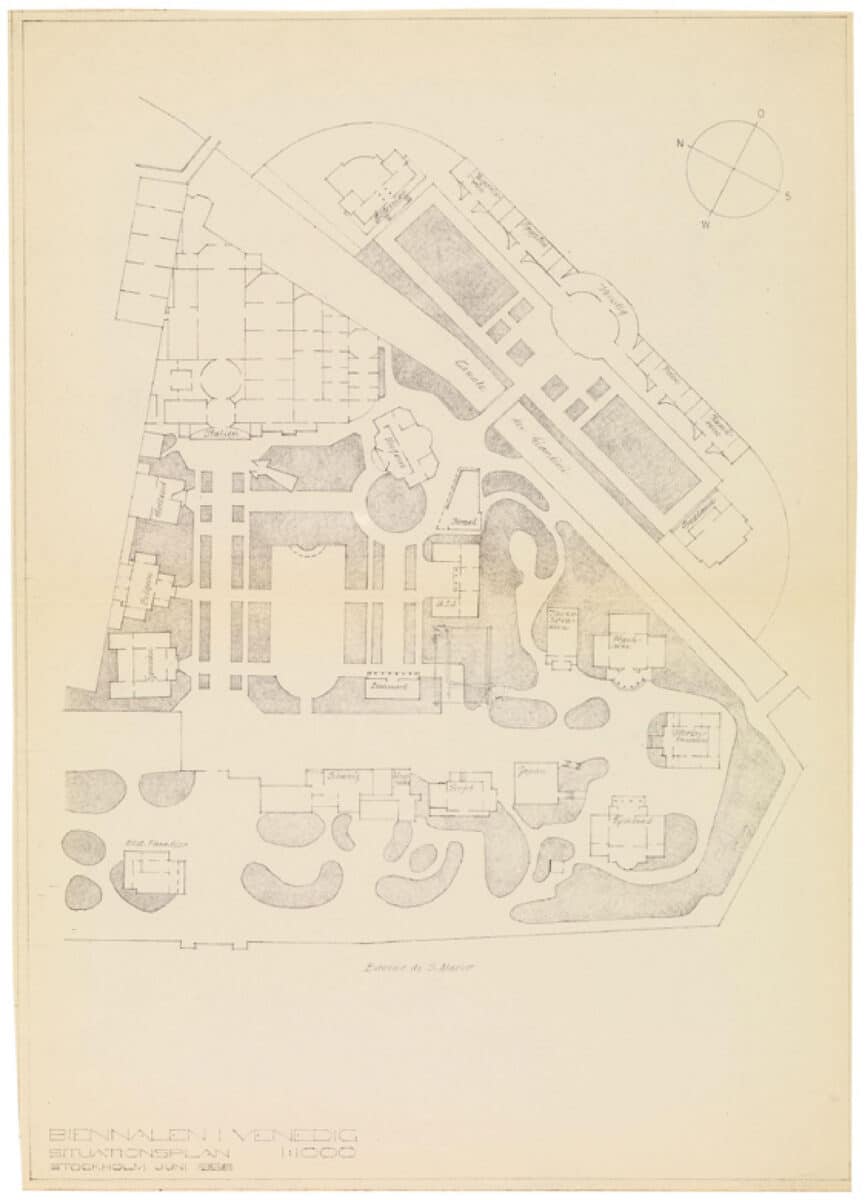

While the Swedes operated expeditiously, the neighbouring countries were slower in appointing jury members and architects, resulting in a flow of telegrams and reminders out of Stockholm. [19] Attempts to finalize the competition brief and appoint the jury by March 1 fell through. Sweden appointed Klas Anshelm, the architect of Lund Konsthall (1957). Finland selected Reima Pietilä, and Norway Sverre Fehn, the architects of the Finnish and Norwegian pavilions at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, respectively. [20] A telegram announced that Iceland would not participate in the competition nor in the jury. [21] The Danish Association of Architects expressed their disapproval with the Danish artists, the New Carlsberg Foundation, as well as the Ministry for turning down the invitation that would have allowed a Danish architect to have taken part in the competition, whereas the Swedish Architects’ Association (SARS) regretted that a Nordic collaboration failed to obtain sufficient support, and complimented Snellman on the considerable effort he had invested in the cause. [22] Later, Nils Koppel, the Danish member on the competition jury, deemed Denmark’s lack of interest a missed opportunity, and announced that he would do everything in his power to ensure that ‘the two pavilions represent a unity’. [23] Hours before the competition was announced, the brief was accepted by the national architects’ associations. [24] On June 28, 1958, the brief was sent to Fehn, Anshelm, and Pietilä, and an update was sent to the jury. [25] The brief was accompanied by a map of the Giardini in scale 1:1000 showing all pavilions, a map of the site in scale 1:200 with adjacent pavilions, as well as plans, façades, and sections of the Danish Pavilion in scale 1:100, prepared by Peter Koch for his first five schematic designs, dated January 25, 1957. In summary, the brief asked for the following: The pavilion should be easily accessible from the north and the west, and facilitate the optimal circumstances for displaying sculpture, paintings, and works on paper. Flexible exhibition spaces should amount to 400 m2. Ideally, the exhibition spaces can be used partly for separate exhibitions by the three countries, or for bigger exhibitions with one or two countries presenting; partly for an ordering of the exhibits not by country but by medium, allowing sculpture, paintings, drawings, and graphic works to be grouped in suitable spaces. The building must have a 15 m2 storeroom. The Biennale demanded a passage south of the Danish Pavilion. And as the Biennale ground is the only park in Venice, the authorities ask that the bigger trees on the site be preserved. [26]

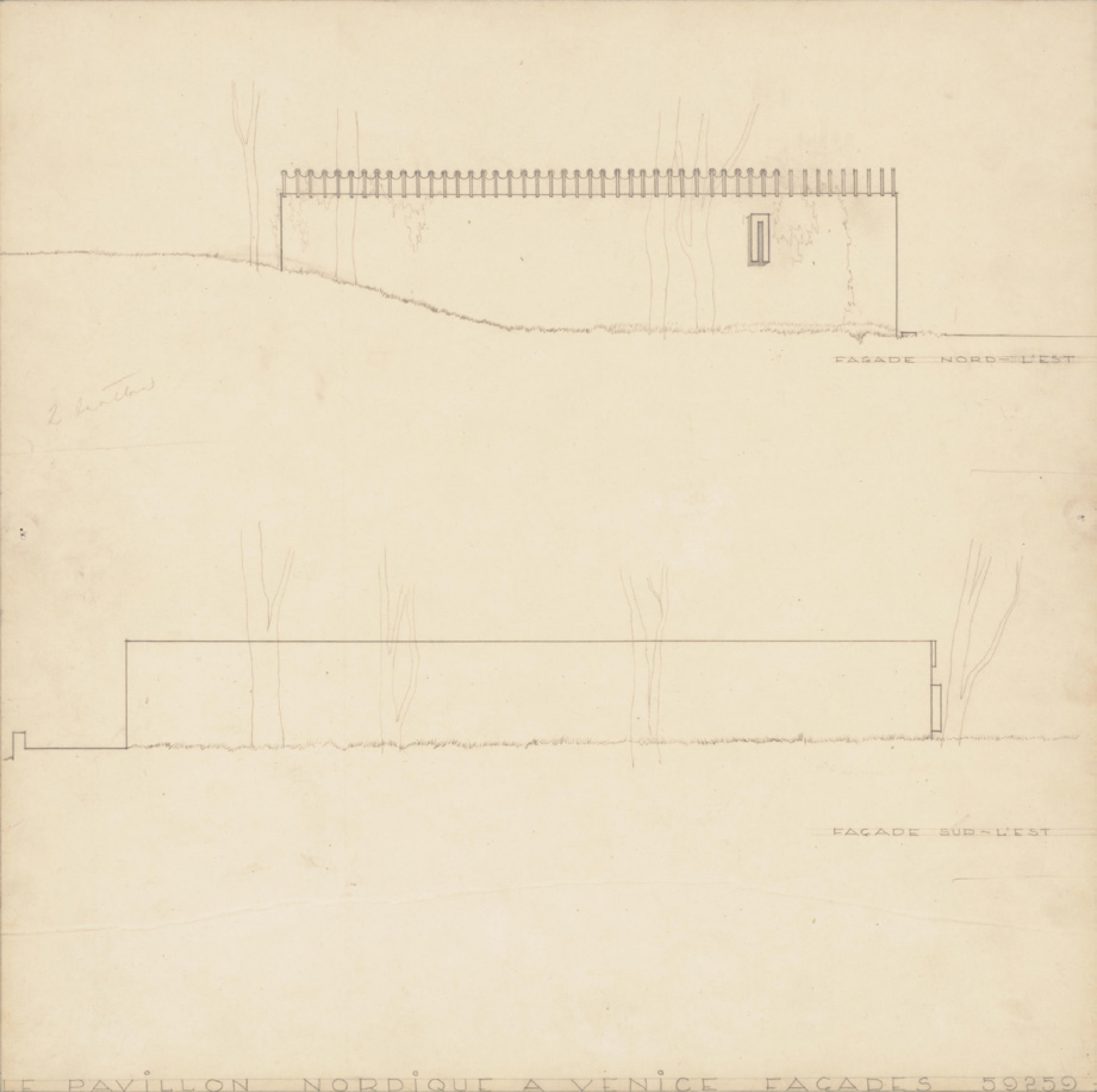

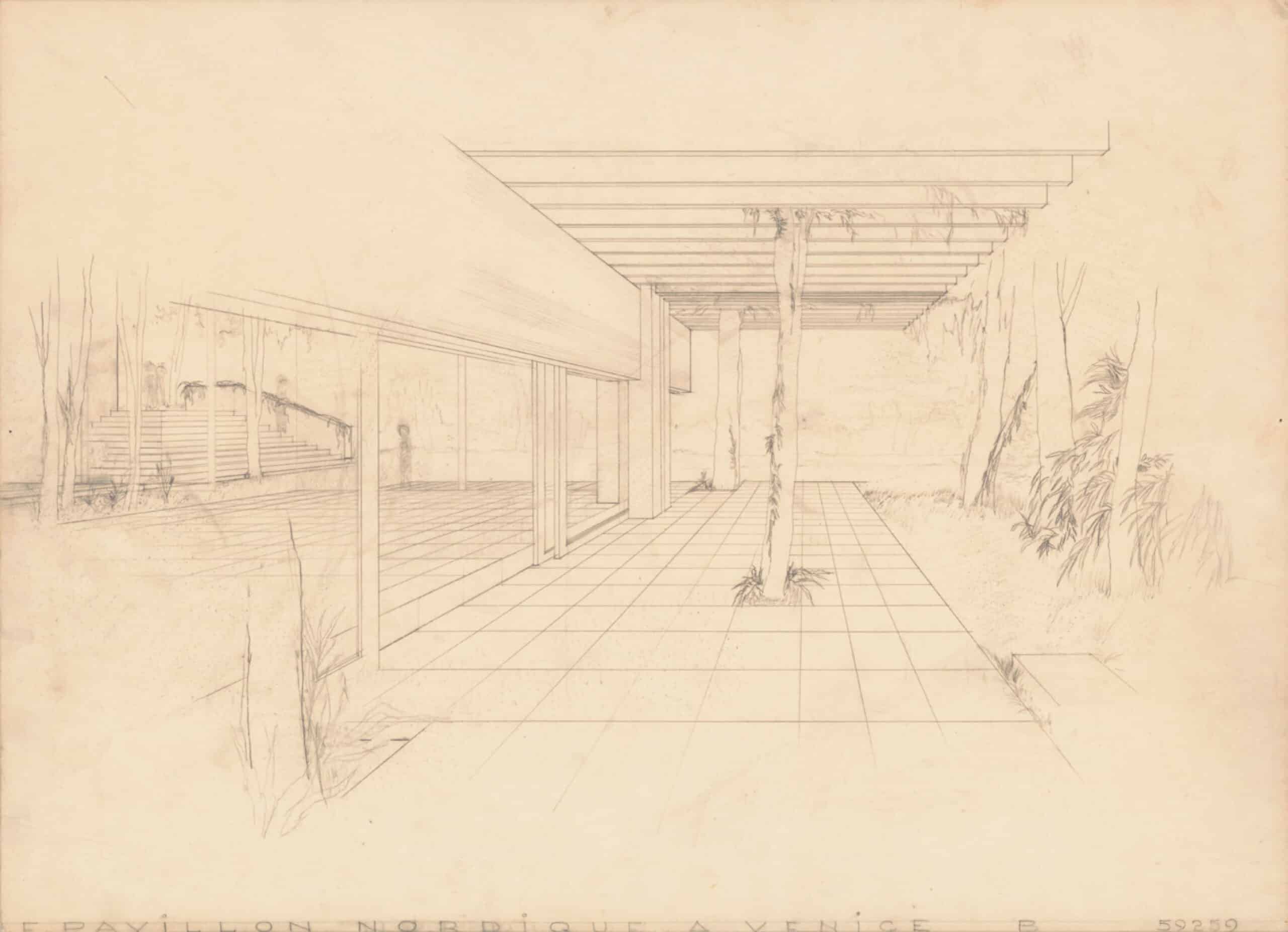

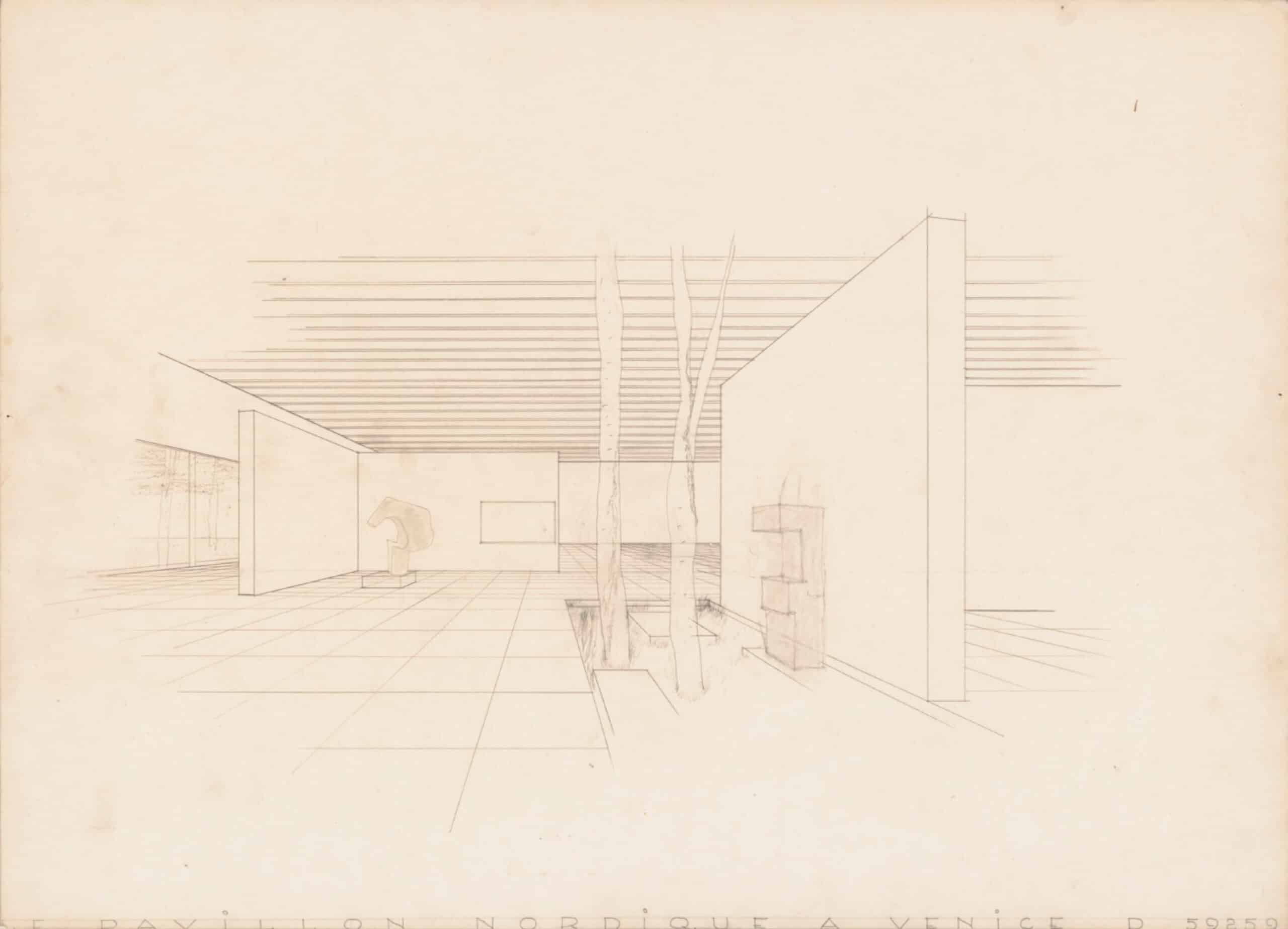

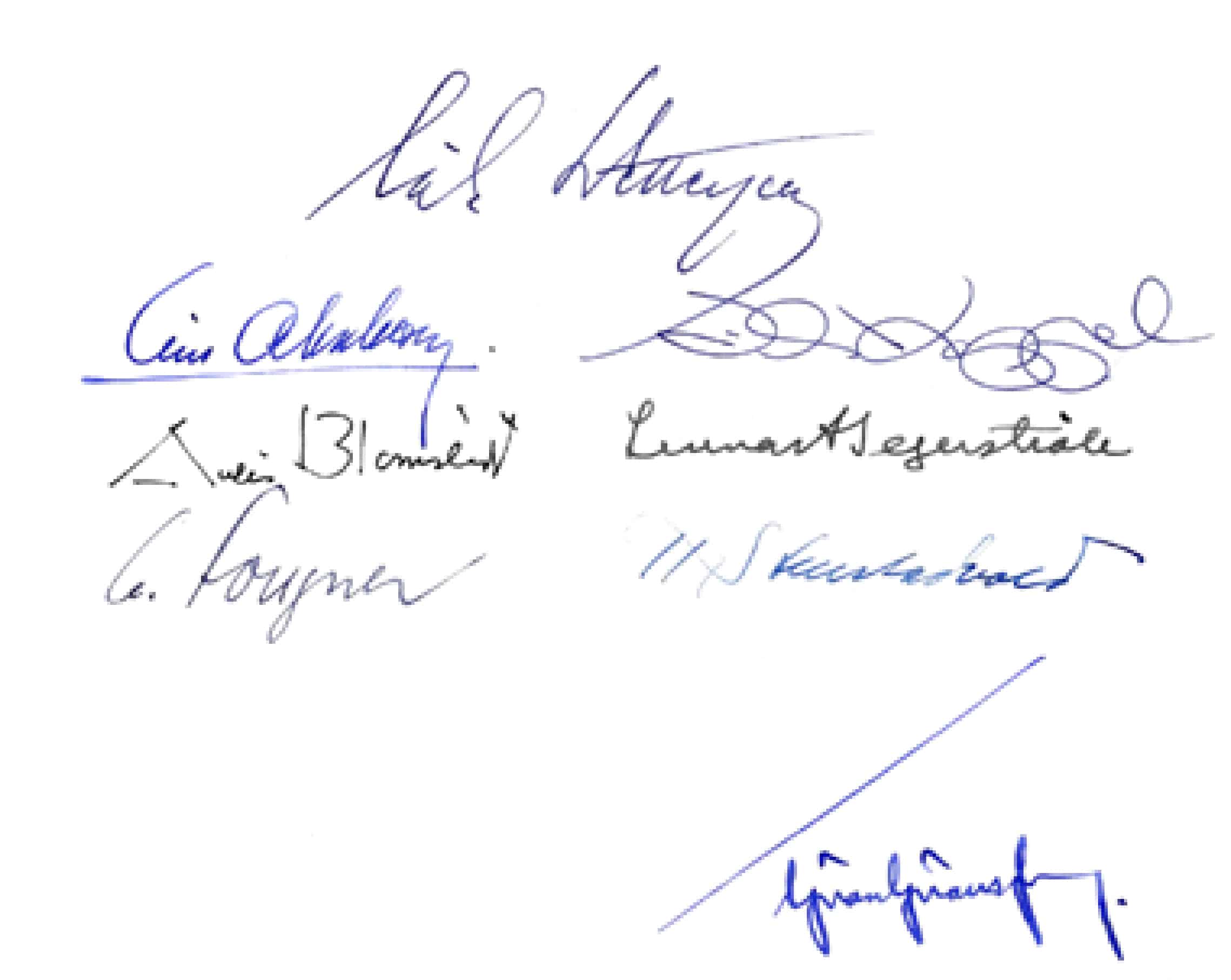

The competitors were asked to submit anonymously a site plan (1:200), plans and elevations (1:100), a plan (1:50) showing the elasticity of the exhibition space, exterior and interior perspectives, and a short typewritten description. Honorarium: 3,000 kroner, and a trip (first-class flight) to Venice with three nights in a hotel. The competition language was French. [27] The French texts would be translated into Swedish prior to the jury meeting. When accepting to sit on the jury, Gunnar Fougner, the Norwegian jury member, suggested that the competitors submit models with the entries. [28] Following this suggestion, the matter kept resurfacing. ‘In regard to the demanding nature of the task, a model is desirable (for instance in 1:200 scale)’, Pietilä expressed in late August. [29] The jury decided that ‘models and other material not being asked for will not be reviewed’, considering it unfair if some handed in models and some not. Fougner again insisted that models of a similar execution be prepared for the jury meeting. [30] Ultimately, the chairman of the jury Nils Ahrbom, confirmed that the models would be ready by early February. [31] The jury met at the Royal Academy of Art in Stockholm, February 14–16, 1959. The architects on the jury were appointed by the national architects’ associations. Sweden was represented by architect Nils Ahrbom and Erik Wettergren, Finland by architect Aulis Blomstedt, Norway by architect Gunnar Fougner and the artist Håkon Stenstadvold, and Denmark by architect Nils Koppel. Four entries had been submitted, as Pietilä submitted two projects. The following declaration was released unanimously by the jury:

The jury has based its deliberations concerning the four entries on the

following five main considerations:

- The pavilion’s accessibility, openness, or enclosure

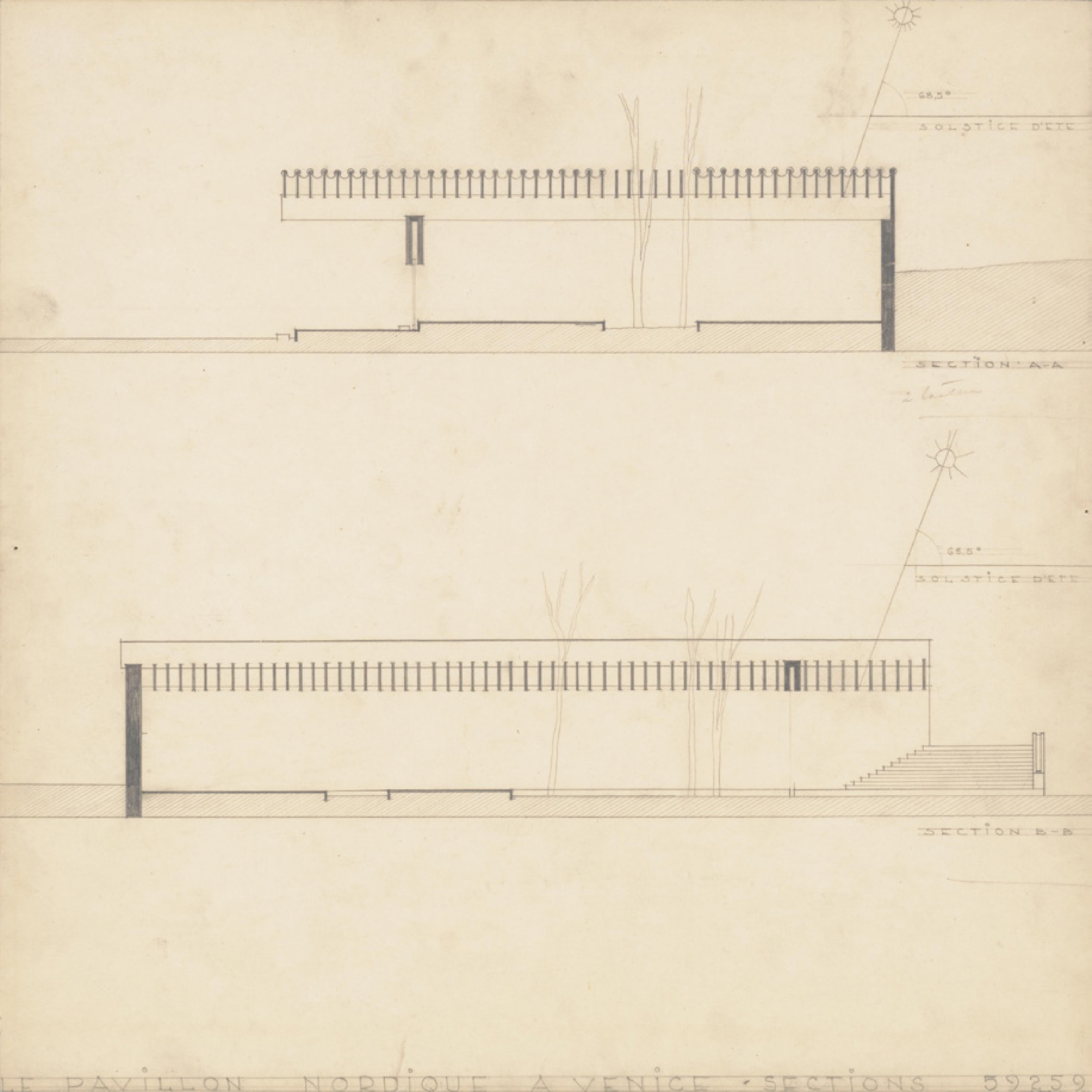

- Technical exhibition considerations, flexibility, light

- Relationship to neighbouring pavilions, terrain, and vegetation

- Construction and materials

- Durability and maintenance

During the following review of the four entries based on these specifications, the relative weight of the various criteria was not initially taken into consideration.

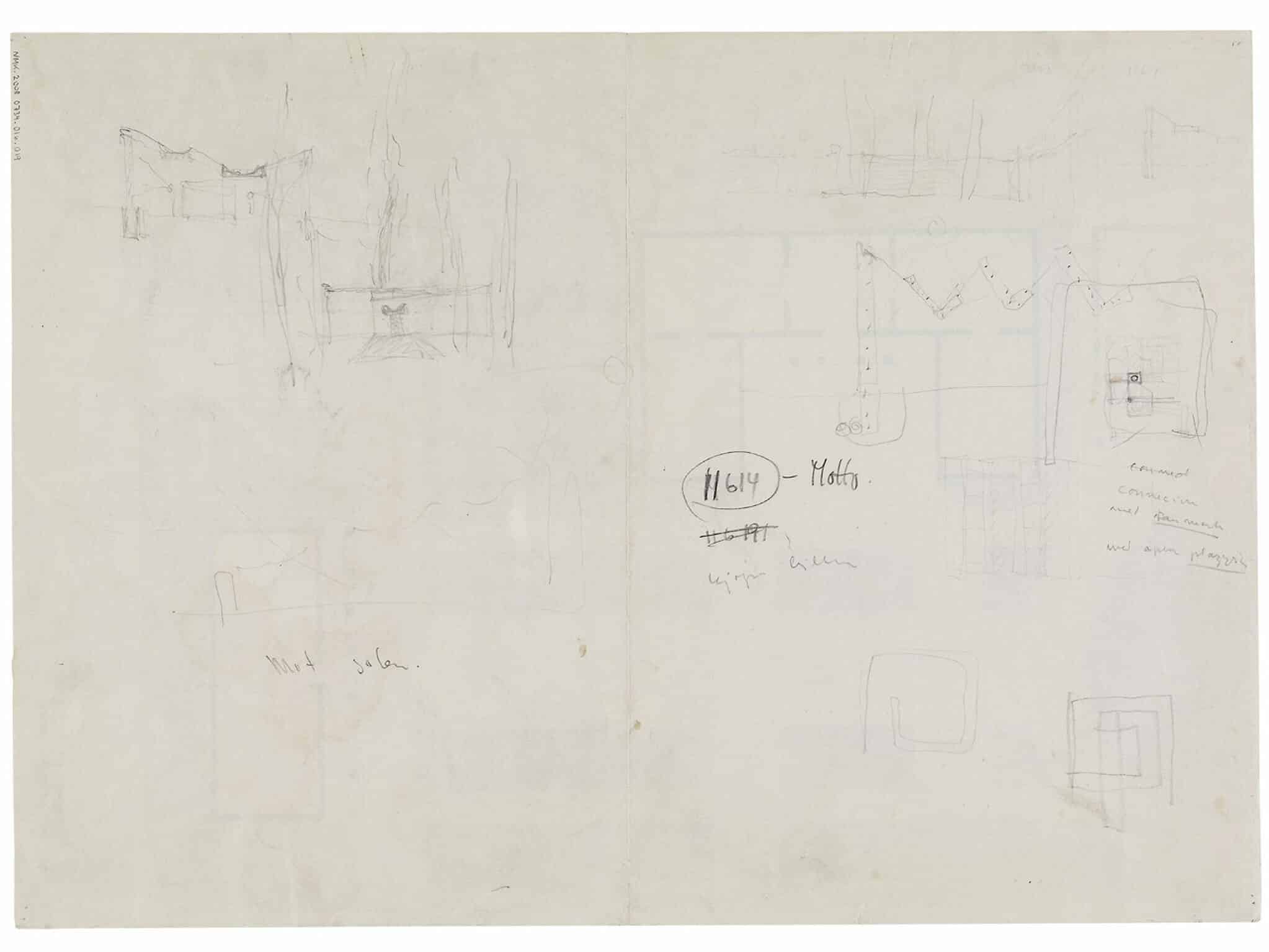

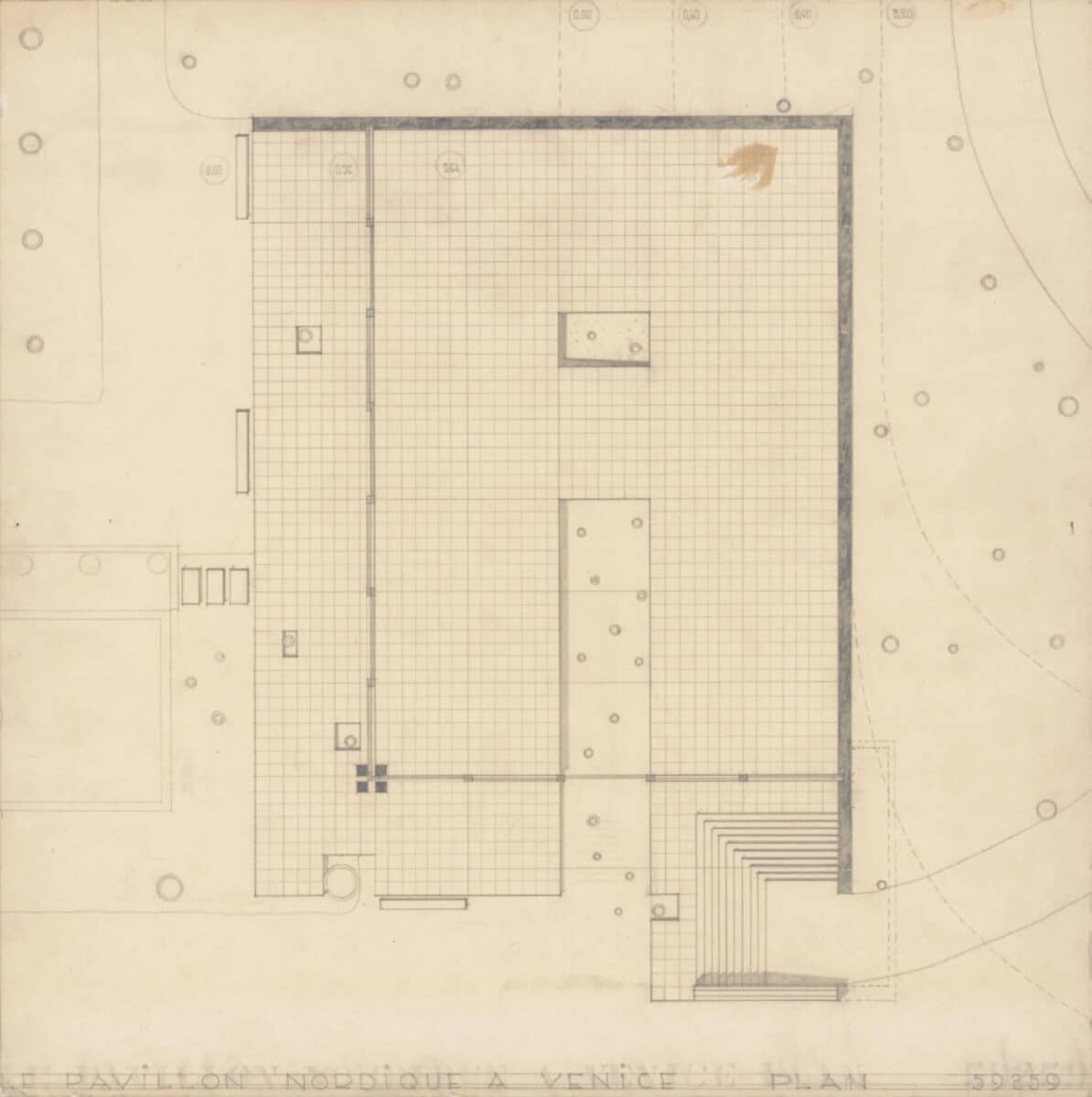

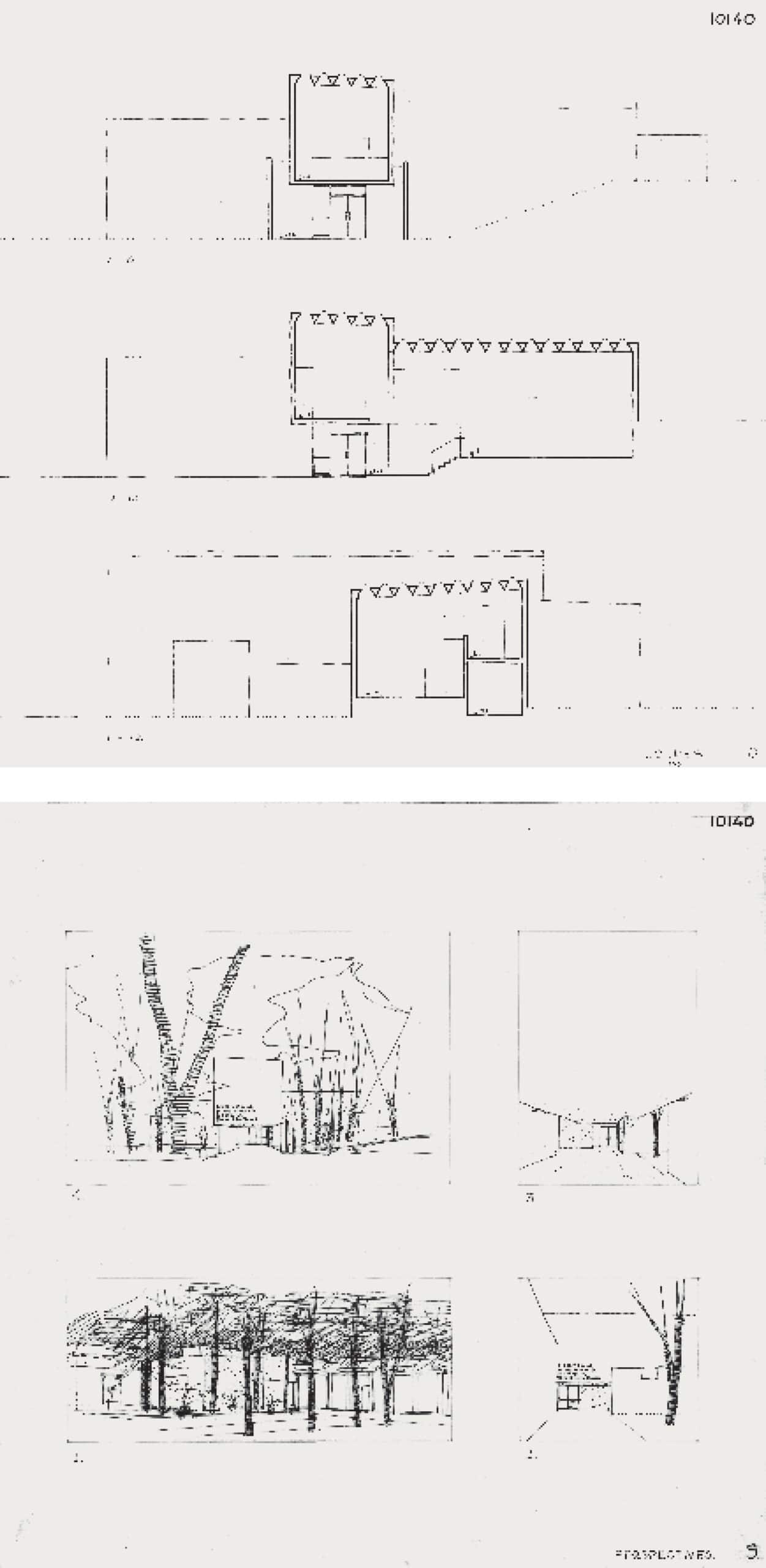

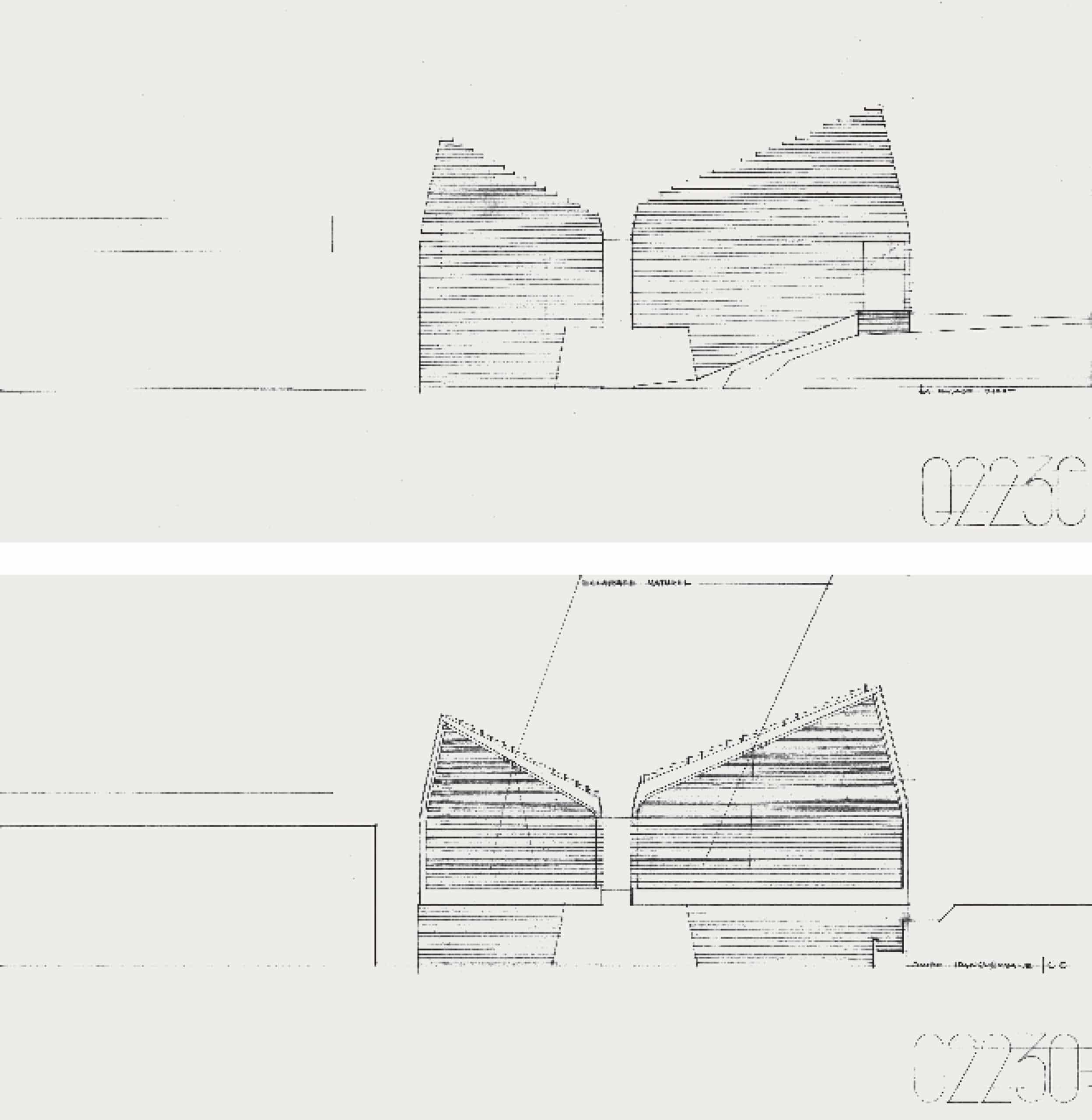

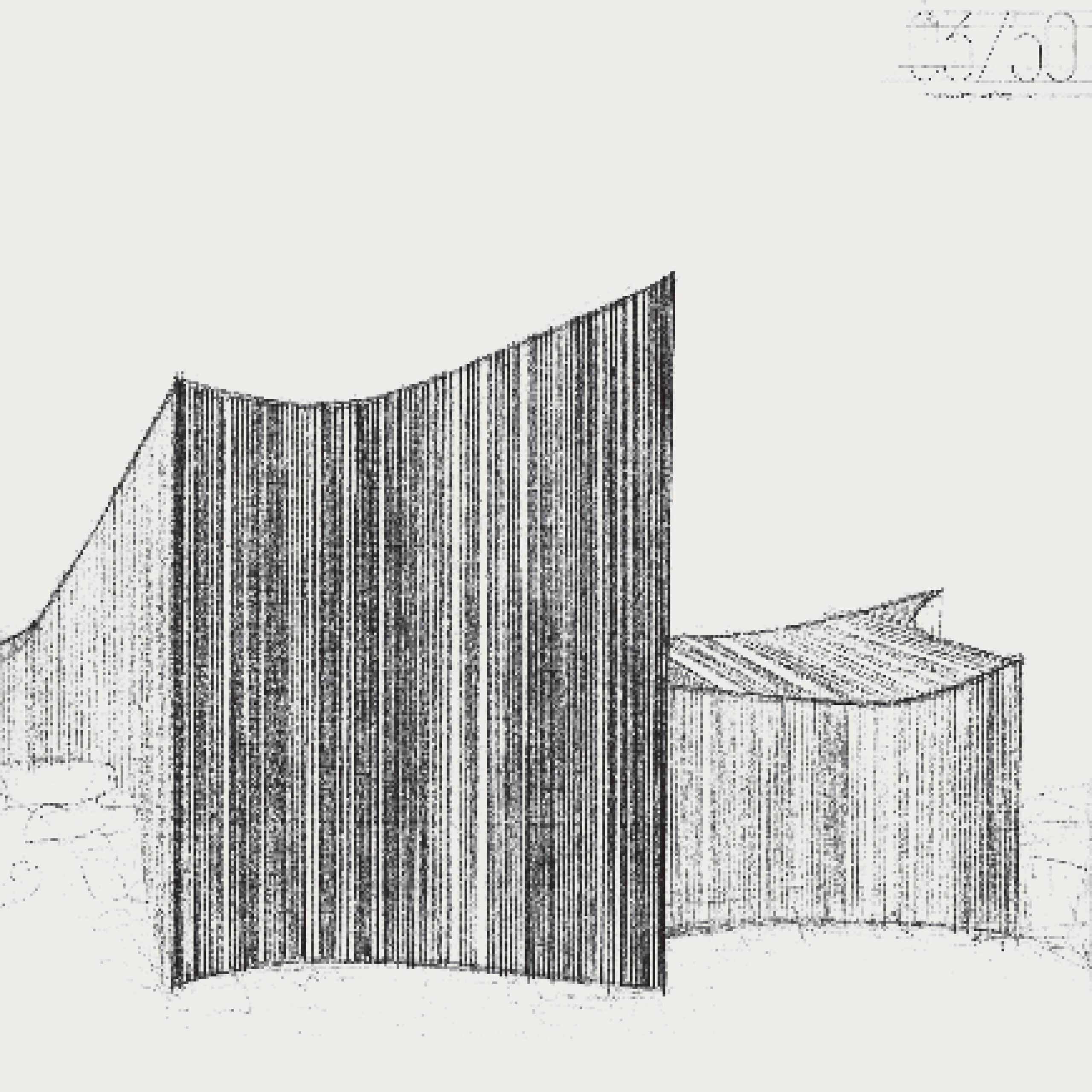

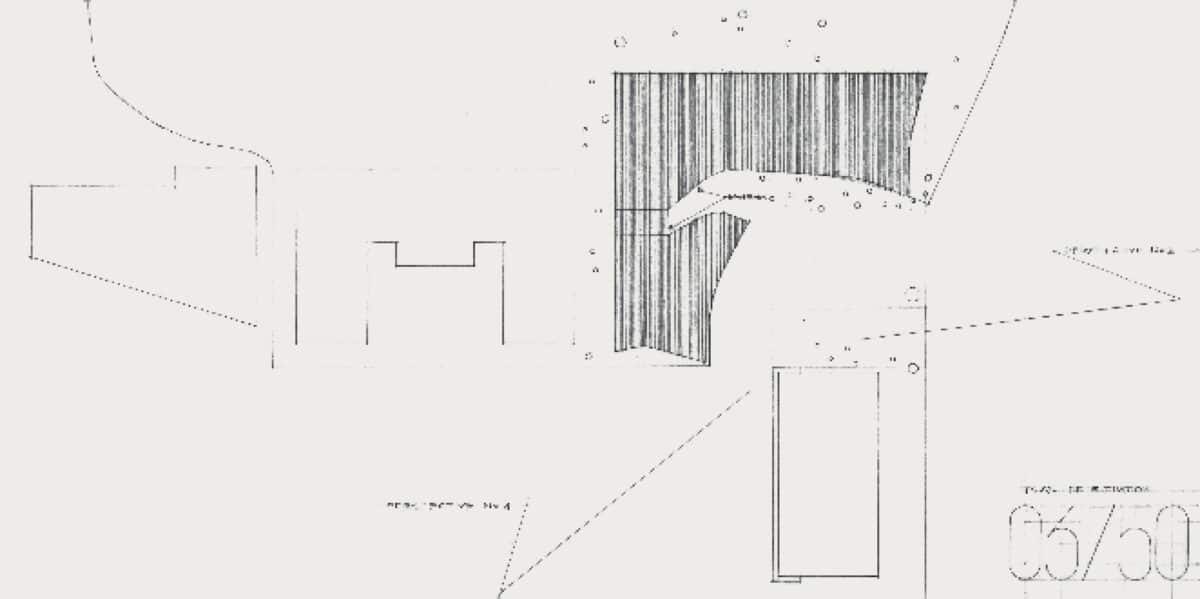

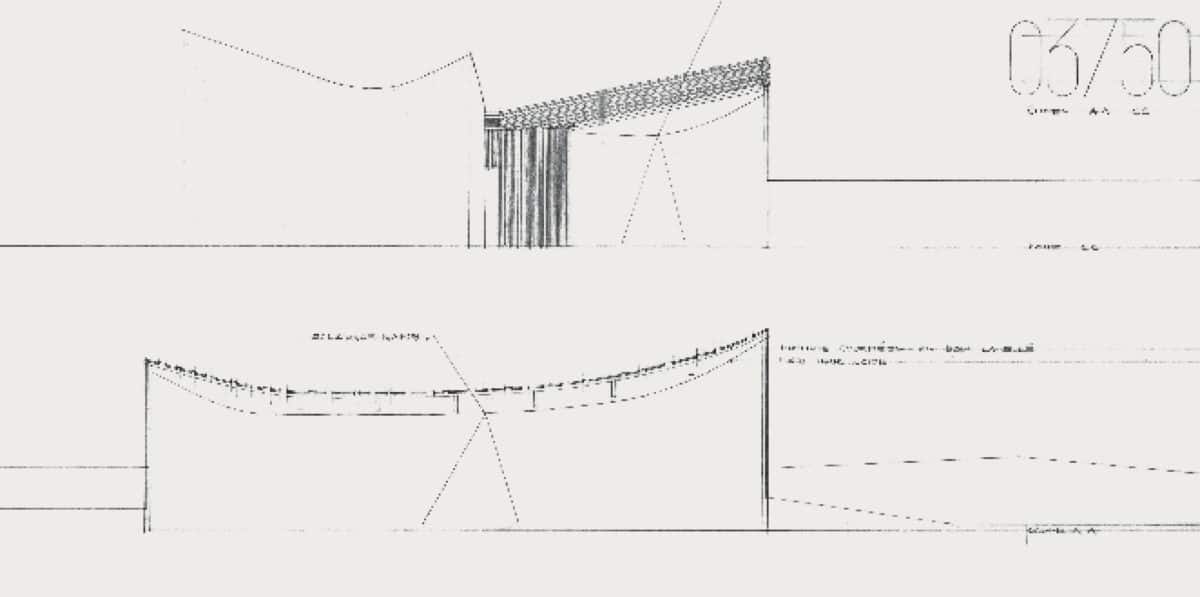

In the following, the individual contributions have been assigned

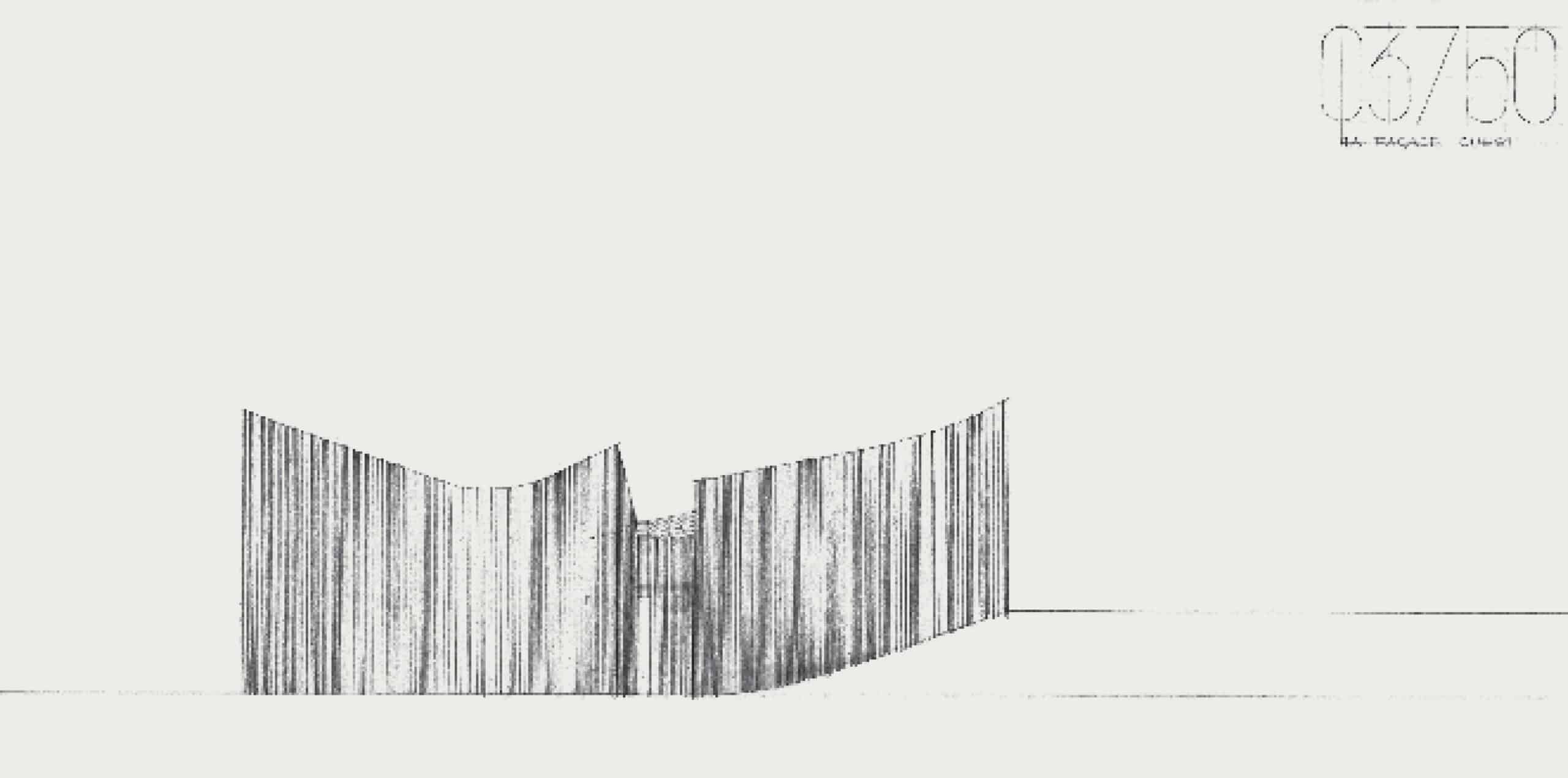

numbers in accordance with their submission, i.e., 10140 is No. 1, 59259

is No. 2, 02230 is No. 3, and 03750 is No. 4.

The pavilion’s accessibility, openness, or enclosure

The assigned plot in the Biennale park is an attractive location from the public point of view, with its close connection to the central ground and the north–south main axis of the Giardini. A dense flow of visitors passes the area on the way from the Palazzo Centrale or the American Pavilion to the pavilions in the southern and western parts of the park, such as the French and British Pavilions. Consequently, the Nordic Pavilion should have an inviting design that captures the public’s interest. Such an interest may be triggered both by complete openness and defined enclosure, which may prompt expectations. Considering the total scope of the Biennale exhibition and the sharp competition between the various nations for the visitors’ attention, one must expect a certain amount of exhibition fatigue, causing the public to choose the path of least resistance. The location and design of the entrances as well as the opportunity for natural flow through the structure is therefore important.

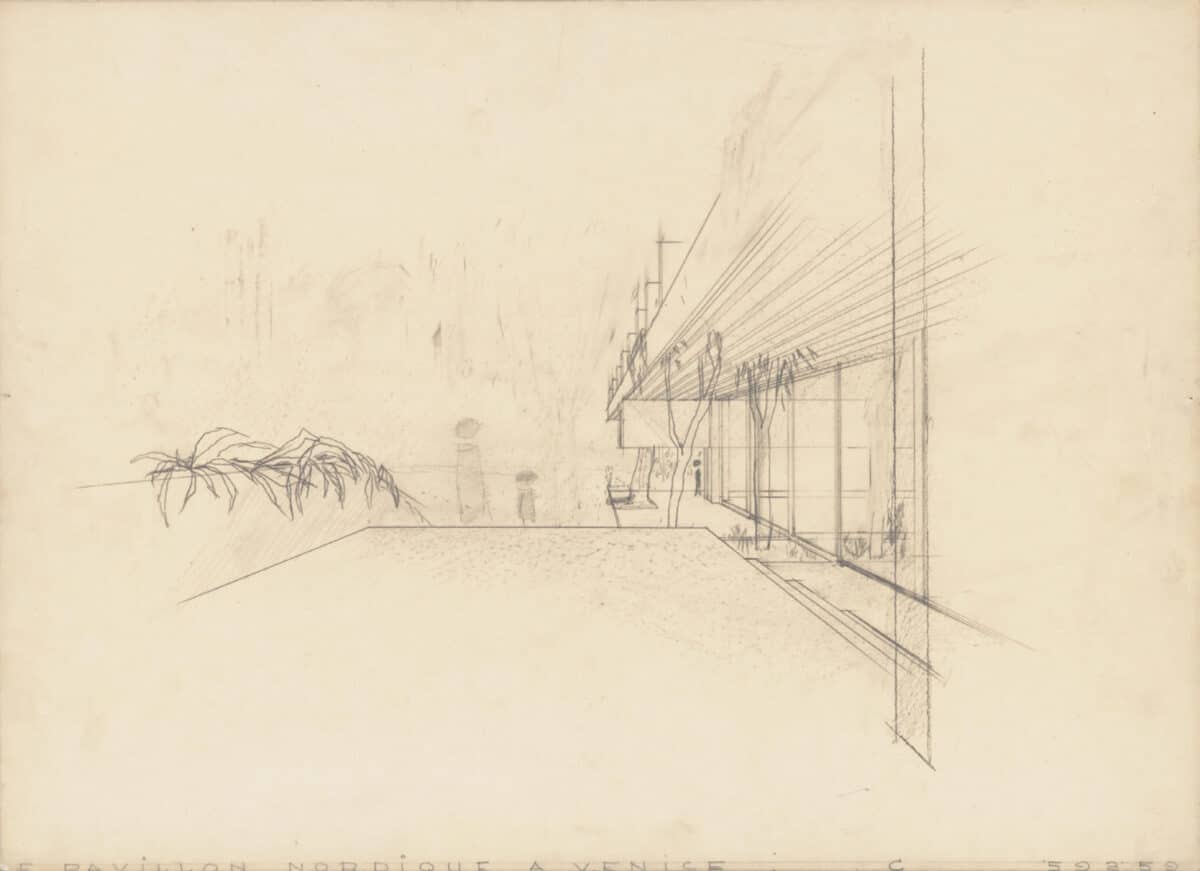

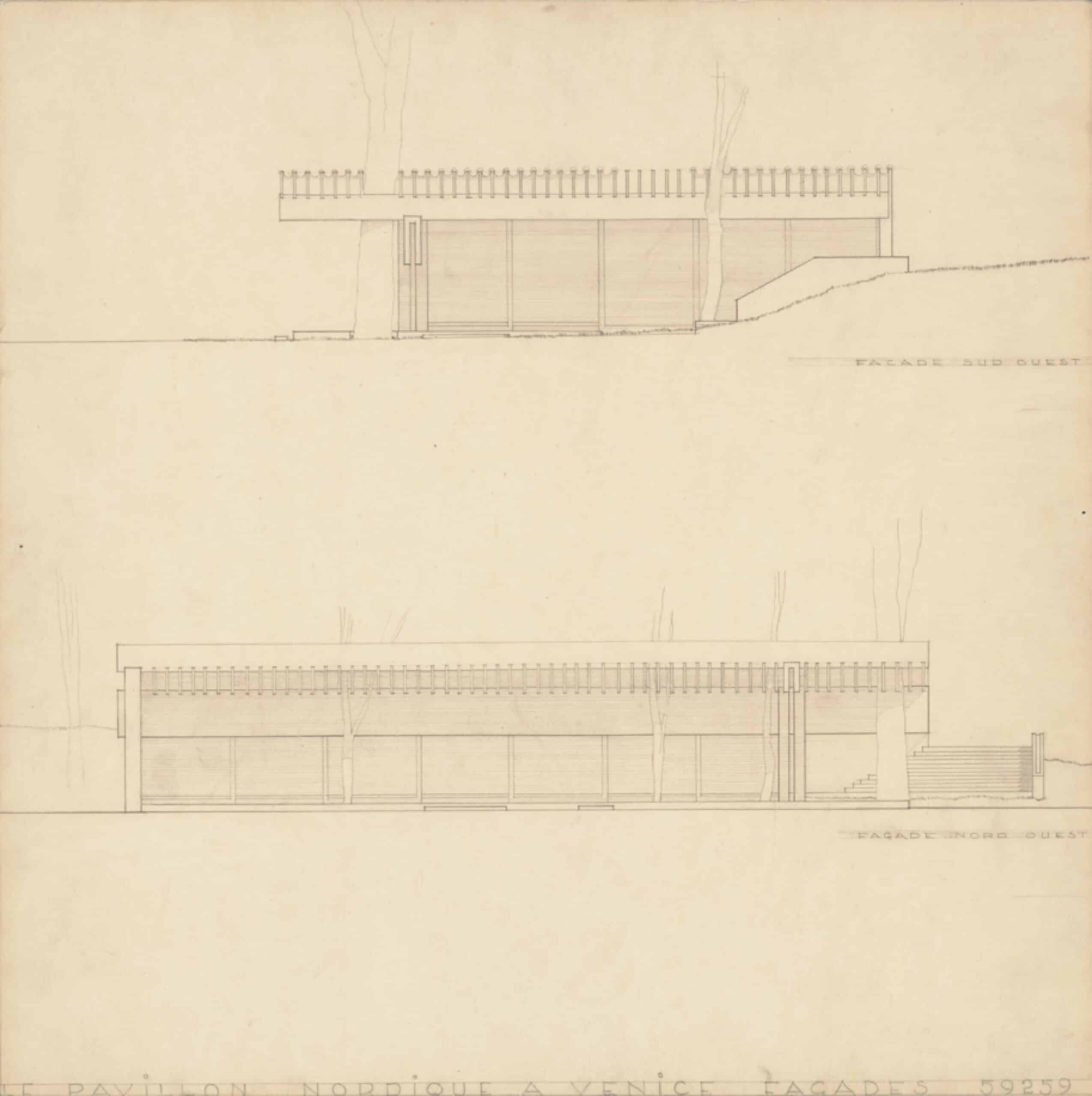

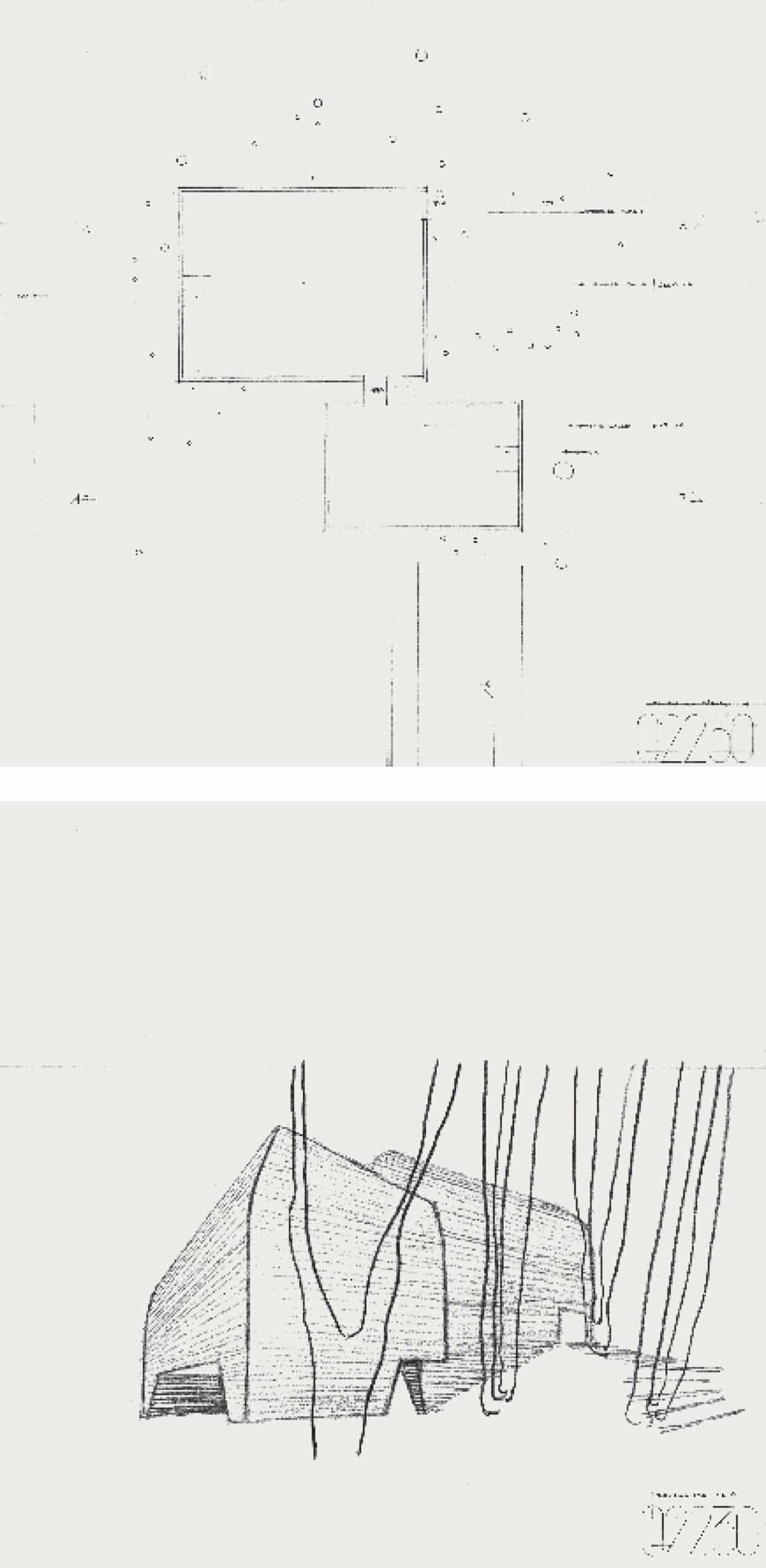

In relation to these criteria, the proposals differ significantly. Proposal No. 2 is completely open toward the north and west, for the main flow of visitors, and gives a good overview of the whole exhibition venue on the ground plane. This contrasts with proposals No. 3 and No. 4, which are focused inward. No. 3 has only one point of entry, located inaccessibly on a higher level with little traffic and hidden from the side facing the central plaza. The entry furthermore lacks contact with the open spaces below. Proposal No. 4 also only has one entry, and out of sight from the central plaza and partly behind trees, which will be preserved, but otherwise it has been given an attractive and interesting design.

In proposal No. 1, the building with its three exhibition halls yields a fairy closed character, but the main entrance is centrally located, also in respect to the flow of visitors. With its two entrances, this pavilion encourages passage between the two levels. However, the portico’s support construction and the main entrance do not provide the desired openness. From the viewpoint here adopted, proposal No. 1 occupies an intermediate position between proposal No. 2 on the one hand and proposals No. 3 and No. 4 on the other.

Technical exhibition considerations, flexibility, light

Proposal No. 1 has three exhibition halls and one gallery on different levels, all connected in an open sequence. As such, the pavilion may be used for three – possibly four – separate exhibitions arranged in various manners. The desired flexibility is thus achieved but also restricted due to the plan. A further division may be achieved by means of screens or similar. Space 3 is fairly narrow and has, exhibition-wise, a different character. The spaces are connected by means of stairs. The upper level gives various views of the exhibited artworks. The storeroom is accommodated for.

The other proposals provide flexibility by means of movable screens and plinths. This principle provides great flexibility but requires that the use of available space is decided specifically for each exhibition. Proposal No. 2 provides great opportunities for variation as the exhibition space is one continuous rectangular hall. The height is limited to four meters for the total space. This proposal even offers external exhibition space in direct communication with the exhibition hall. The storeroom tentatively located under the staircase is difficult to utilize.

The subdivision of the exhibition spaces in proposals No. 3 and No. 4 into two more or less separated rooms seems to be based primarily on concerns regarding the exterior but nevertheless allows changing use of the exhibition spaces. The curvature of the walls in both plan and section limits to some extent the rational utilization of the exhibition space for both proposals. The two storerooms in proposal No. 3 are difficult to access.

All proposals are based on natural light for the exhibition areas, which is an appropriate principle considering the number of trees surrounding the pavilion. Proposal No. 1 offers a straightforward and technically feasible solution for the skylight, and shows a reasonable roof inclination. The skylight in proposal No. 2 is suitable but technically unresolved. The lighting in proposals No. 3 and No. 4 should also be suitable for the exhibited works of art. None of the proposals has considered light reflections from paintings with shiny surfaces.

Relationship to neighbouring pavilions, terrain, and vegetation

Here, the most important aspect is the pavilion’s location in relation to the Danish Pavilion, with which certain connections should be established from both an idealistic and practical point of view.

The proposals No. 1 and No. 4 offer particular solutions in this respect. Both present courtyards for showcasing sculpture. Proposal No. 3 does not sufficiently address this relationship, yet it does suggest a separate area toward the American Pavilion. With its roof construction and the flooring, proposal No. 2 occupies the entire corner between the Danish and American pavilions. In regard to volumes, proposal No. 1 relates most closely to the adjacent pavilions. However, the part closest to the American Pavilion breaks with the building line given by the neighbouring pavilion.

The latter proposal is the only one to employ the levels of the terrain in order to achieve varying exhibition levels. The others, excepting No. 3, are dug into the ground to obtain exhibition space on one level. Above the height where tree branches spread out, the buildings will by and large not be visible. This aspect has, in different manners, been considered in proposals No. 1 and No. 2—in the first case by a neutral building volume, in the second case by a pronounced limitation of the building heights. The sculptural forms of proposals No. 3 and No. 4, which are assigned significant artistic significance by the authors, will to a large extent be lost.

All proposals have, in various ways, endeavoured to fulfil the desire to retain the vegetation on the exhibition site.

Construction and materials

Proposal No. 1 is largely technically feasible according to the author’s guidelines. The support construction for the portico is, however, unclear from a construction point of view and difficult to execute. In addition, the beam construction establishes an undesirable visual barrier, particularly toward the Danish Pavilion.

The roof construction in proposal No. 2 is not fully described and to a certain extent not technically resolved. The water drainage system is not described. The proposed horizontal cover with glass or plastic tiles will not produce joints sufficiently sealed to avoid water penetration. Also, the roof design around the tree trunks is not satisfactorily resolved.

Proposals No. 3 and No. 4 are impregnated wood structures covered externally with copper bands of varying widths and internally with wooden panels. The roofs are in copper and glass. A satisfactory solution for water drainage may pose problems in proposal No. 4. In both proposals, the choice of materials might be less suitable, considering the humid climate and the hot summers. From a climatic point of view, a stone construction as in proposal No. 1 or a completely vented structure as in proposal No. 2 will be preferable.

Durability and maintenance

It should be particularly observed that the pavilion will only be used in the summer season every second year, and that significant emphasis should be put on its durability and requirements for continuous maintenance. The technical simplicity of proposal No. 1 meets these considerations. The roof construction might cause problems, as indicated in section 4. The durability of proposals No. 3 and No. 4 is insufficient with regard to the choice of materials, even if the woodwork would be impregnated as suggested. The internal tent-ceiling in proposal No. 4 will be expensive from a maintenance point of view.

Based on the above review of the proposals, the jury has agreed on the following summary.

Proposal No. 3 does not satisfactorily fulfill the purpose. The same applies to proposal No. 4, although this has a suggestive design of notably artistic significance. Proposals No. 1 and No. 2 are more neutral designs and adapt themselves, each in its own manner, to the purpose of the pavilion. Of these two proposals, the committee consider No. 2 superior to No. 1, also in its greater openness, accessibility, and in the significant opportunities it offers for a variety of exhibitions. With its placement in the flow of visitors, and considering the dense vegetation, the jury has found it particularly deserving that the pavilion may be characterized as more or less a covered part of the park. The idea of the proposal is a worthy basis for realization.

The jury is, however, of the opinion that several parts of the proposal need alteration. Primarily, this applies to the relationship with the Danish Pavilion. In the current plan, the distance to the Danish Pavilion causes the pavilion to appear neither freestanding nor attached. Further, the roof construction should leave more space for the tree trunks and the covering must ensure appropriate sealing.

The jury unanimously proposes that entry No. 2 with motto No. 59259 form the basis for a common pavilion for Finland, Norway, and Sweden at the Venice Biennale and that its author is commissioned as the architect for this building. [32]

Notes

- Press release. February 18, 1959. [SvR1]

- Announcement, Ragnar Edenman, Minister of Ecclesiastical Affairs on behalf of his Majesty, March 28 1958. [SvR1]

- Letter from Ragnar Edenman to the MFA, Stockholm, March 28, 1958. [SvR1]

- Letter from Wettergren to Vøhtz, Secretary General, Ministry of Education / Den danske komite for Biennalen i Venedig, February 2, 1957. [SvR1]

- Protokoll, Svenska biennalkommittén, Konstakademien, December 16, 1957. [SvR1]

- Protokoll, Svenska biennalkommittén, Svenska slöjdföreningen, May 14, 1958, §6. [SvR1]

- Letter from Wettergren to von Post, April 24, 1958. Letter from von Post to Wettergren, April 25, 1958. [SvR1]

- Letter from von Post to Wettergren, May 10, 1958. Letter from von Post to Göransson, June 6, 1958. [SvR1]

- Letter from Marsano, the Swedish consul in Venice, to von Post, October 10, 1958. [SvR1]

- Letter from Wettergren to von Post, September 16, 1958. Letter from Göransson to Mario Vianello-Chiodo, October 11, 1958. [SvR1]

- Letter from von Post to Wettergren, October 14, 1958. [SvR1]

- Göransson, P.M., January 14, 1959. Letter from Wettergren to von Post, February 27, 1959 Letter from von Post to Wettergren, March 4, 1959. [SvR1]

- Letter from Segerstråle to Göransson, June 26, 1959. Letter from Stenstadvold to Göransson, October 13, 1959. [SvR1]

- Protokoll, Svenska biennalkommittén, June 13, 1960. [SvR1]

- Protokoll, Svenska biennalkommittén, April 19, 1958. [SvR1]

- Letter from Göransson to Verner Hammer, Ministry of Education, Copenhagen, May 16, 1958. [SvR1]

- Letter from Vøhtz to Göransson, June 4, [SvR1]

- Agnete Vøhtz, “Biennalen i Venedig,” Memo, January 28, 1960. [Kbh.]

- Telegram from Wettergren to Stenstadvold and Segerstråle, May 27, 1958. Protokoll, Svenska biennalkommittén, Konstakademien, May 28, 1958. [SvR1]

- Ibid. Telegram from Segerstråle to Göransson, May 31, 1958. Letter from J. Jervell Grimelund, Secretary General, Norske arkitekters landsforbund (NAL), to Stenstadvold, June 18, 1958. [SvR1]

- In a telegram of June 6, 1958, Iceland’s state architect Hörður Bjarnason

conveyed that Iceland would not participate in the competition. Letter from Magnus V. Magnússon to Wettergren, June 23, 1958. [SvR1] - Letter from Bent Røgind, Danske Arkitekters Landsforbund (DAL), to Snellman, June 25, 1958. Letter to Røgind from Gunnar Lindman, Svenska Arkitekters Riksförbund (SAR), undated. [SvR1]

- Letter from Nils Koppel to Göransson, February, 20, 1959. [SvR1]

- Protokoll, Svenska biennalkommittén, June 26, 1958. [SvR1]

- Letters from Göransson to Sverre Fehn, Klas Anshelm, Reima Pietilä, and the members of the jury, June 28, 1958. [SvR1]

- Program for the competition for a Nordic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, signed by Wettergren and Göransson for the Nordic Biennale Inquest committee, dated Stockholm, June 1958. [SvR1]

- Protokoll, Svenska biennalkommittén, January 15, 1959, appendix. [SvR1]