Future Scenarios, Part II

Work on paper

– Niall Hobhouse and Nicholas Olsberg

FRAGMENTS: THE BUILDING SITE AND THE RUIN

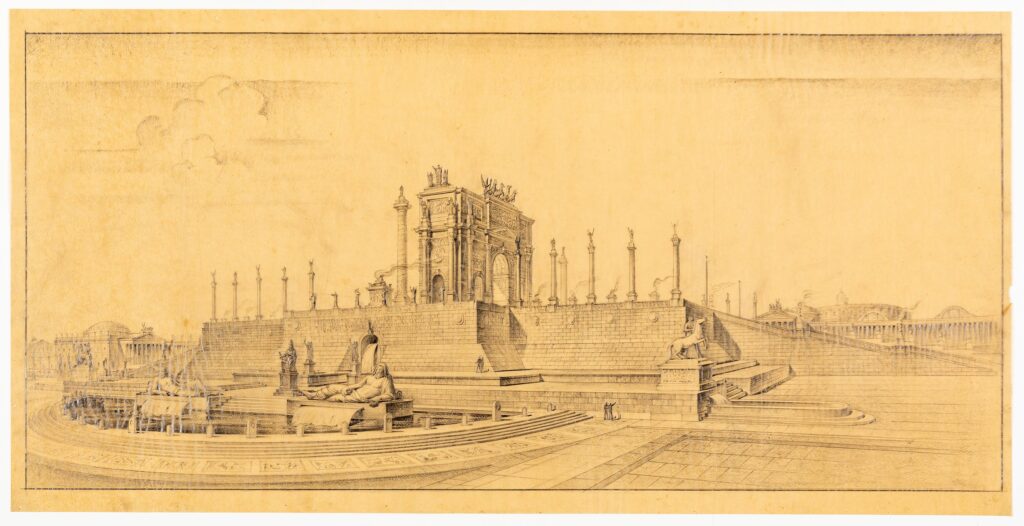

Louis-Jean Desprez turns to another legendary city of the ancient world — Alexander’s capital in Egypt — to advocate in a dream view of Alexandria in construction what great ambitions might be aroused in the new king of Sweden, after his predecessor, who had been the architect’s great patron, had been assassinated.

There is much to be said about the place of city dreams in the imagination of those already too powerful, when even an emperor of the world like Elliot must imagine vast divisions of cities greater yet than he could build.

Yet, as the figures would know who turn from the old world under Reiss’s rainbow’s arc toward a resplendent vision of the new, any dream of a radical new urban order — even those of emperors (or Robert Moses) — is also tuned to the melody of that other Wordsworth who saw in ruins the “still sad music of humanity” and delighted in the melancholy lessons they could teach.

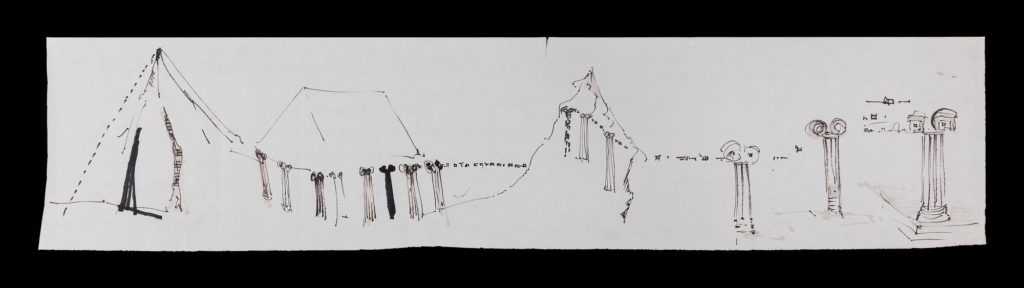

That might not be why students launched themselves upon observations of the rem- nants of time with such revelrous brio as we see in Charles Stanislas Léveillé’s caprice of a medieval ruin. Ironically it was the very uncorruption of ruins that drew scholars of ornament and order to them. Naked masonries seemed somehow larger and purer from the evident aspect of loneliness they wore, as — for example — a great palace that no longer served anyone but a shepherd for shade or a tree for anchor.

Desprez’s ancient city derives from a largely speculative view of a definite past. We have seen before how Armando Brasini borrowed from a much more exact knowledge of imperial Rome to suggest how a new fascist “imperial” order, stretching to the Baltic, might celebrate its northern tier in a Foro Germanico that outstripped even the megalopolitan fancies of Trajan.

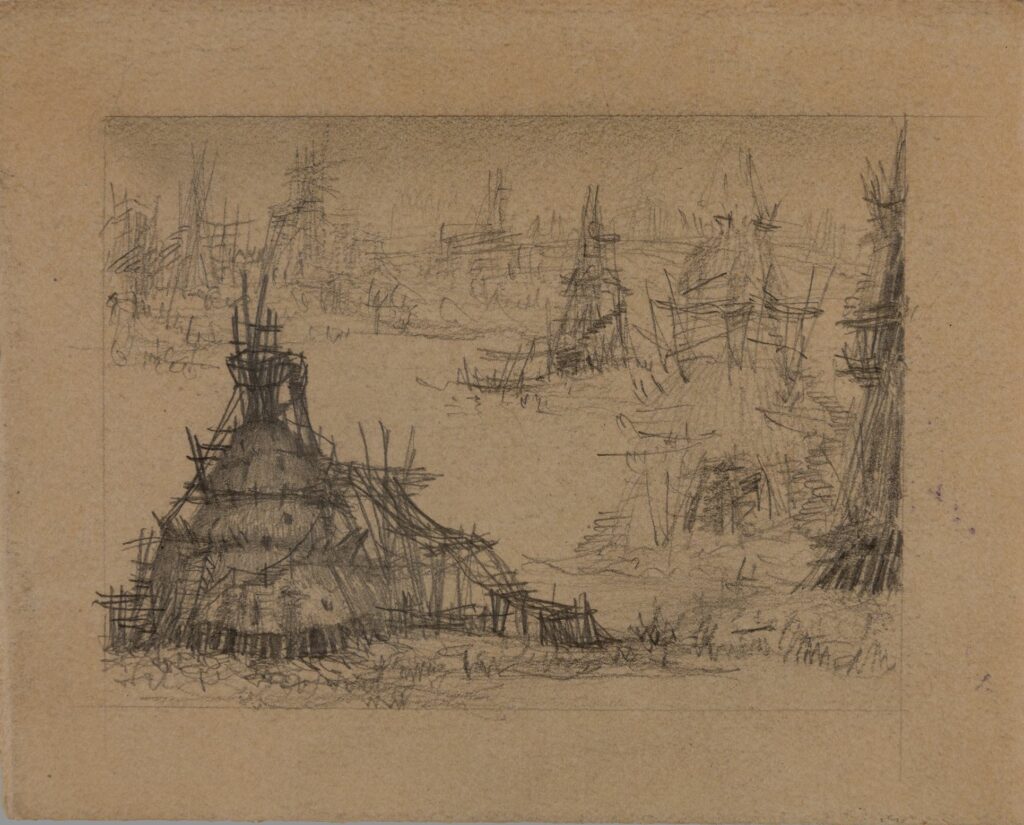

The Soviet architect Boris Iofan, who served a long apprenticeship under Brasini, echoed these grandiose returns to a classical language — marked by a similar triumphalist sense of coming domination — in his sweeping and partly realised plans for postwar reconstruction, like those for the destroyed port city of Novorossiysk.

But what really generates our pleasure in such grand designs is not the possibility of their being built but that, living largely as drawings, they defy the likely fragmentation Aldo Rossi makes so clear. No city, at least for long, can show the steady aspect of a comprehensive architectural plan.

There may be an evolving logic to the patterns and conjunctions with which its urban fragments collide — a distinctive and inherent native geography — but what we live with in any age in every working landscape is a mix of leftover ideas and times. So in the real city we cannot fall romantic victim to either the ecstatic lunacy of rejoicing in the wholly new, or the sublime nostalgia of the totally and forever lost.

Much as they love to dream of building, architects actually seem oddly affectionate about the prospect of ruination. They may not always wish it on their own works — only Cedric Price had the lofty stance for that — but such constructions as Paolo Posi’s for the Roman Chinea or the wood temples in a Catalonian St Joseph festival were designed, like Jean Tinguely’s famous self-destructive machine, to put an end to themselves.

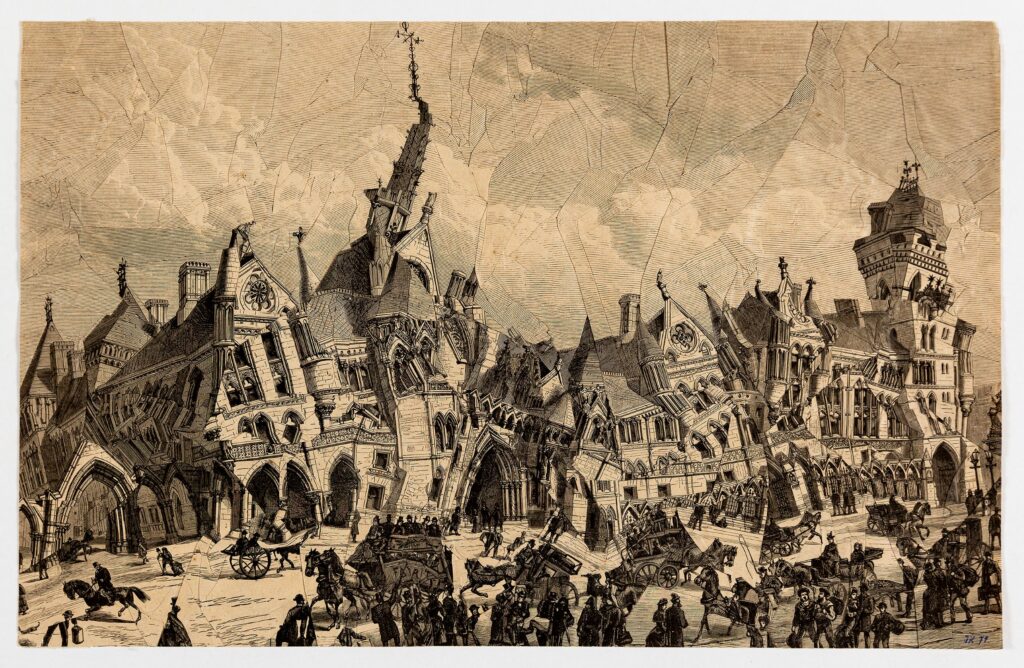

Sometimes that willed destruction is more defiant and illusory than real. Losing all possibility of building new things in Stalin’s Russia, Iakov Chernikhov in his late romances imagined cities built as perhaps Rossi would have asked out of piling up village archetypes, but mounting them in such anti-linear fashion that they appeared always close to tumbling down.

Jiri Kolar did something similar in “crumpling” a traditional Czech townscape.

Is it too much, too, to think that the delight we take in the section and the cutaway perspective (or in the Lutyens doll’s house for Queen Mary) arrives not just because they show us the secret of what is inside but because they effectively demolish at least one supporting skin of the building?

The idea of the section reaches its apogee with Gordon Matta-Clark, essentially an architectural fantasist for whom abandoned buildings served as a canvas, and whose major works are all “intersects” in which he cuts into soon to be demolished structures to make visual poetry of the voids that remain, and of the great suspended dances that went into their excision.

At some point, looking on photographs of works that might never have been seen, in buildings with no future, and coloured by our knowledge of how soon he died himself, Matta-Clark seems to be all about haunted absences, the holes in the whole, and the impending deaths even of remnants and ruination.

– Niall Hobhouse and Nicholas Olsberg