Freddie Phillipson ‘The Ulysses Project’ – Review

The exhibition of Freddie Phillipson’s drawings reconstructing the Dublin of James Joyce’s Ulysses opened on Bloomsday, helping to celebrate the centenary of the publication of the novel. The exhibition is essential viewing for anyone interested in how the European city and its architecture support a culture, and for anyone interested in how drawing can serve as a vehicle for disclosing the nature of architectural and urban order.

In my view, Ulysses is the best account of a city, and of how urban life has been the receptacle of European culture – far superior to anything written by architects, planners, sociologists, or anthropologists. It accomplishes this by concentrating upon the life and thoughts of the middle and lower classes, virtually ignoring all the institutions that would be represented in bold on a Baedeker map of Dublin. In 1904 (the year of the novel), ‘dear dirty Dublin’ suffered one of the highest death rates in Europe with, by some estimations, an average of nine people per room. Joyce recognised that cities do not thrive on idealised types – e.g., homo economicus – but rather on people who only partially understand or who misunderstand, who are as likely to be self-interested as they are generous, as much violent as calm, as much sinful as saintly, as much lost in the field of references as adherent to a creed. Written at a time when the metropolis was a regular topic in the arts as well as in the emerging social sciences, Ulysses also reminds us what we are losing as we decant urban order to digital management and unrestrained land-capitalisation.

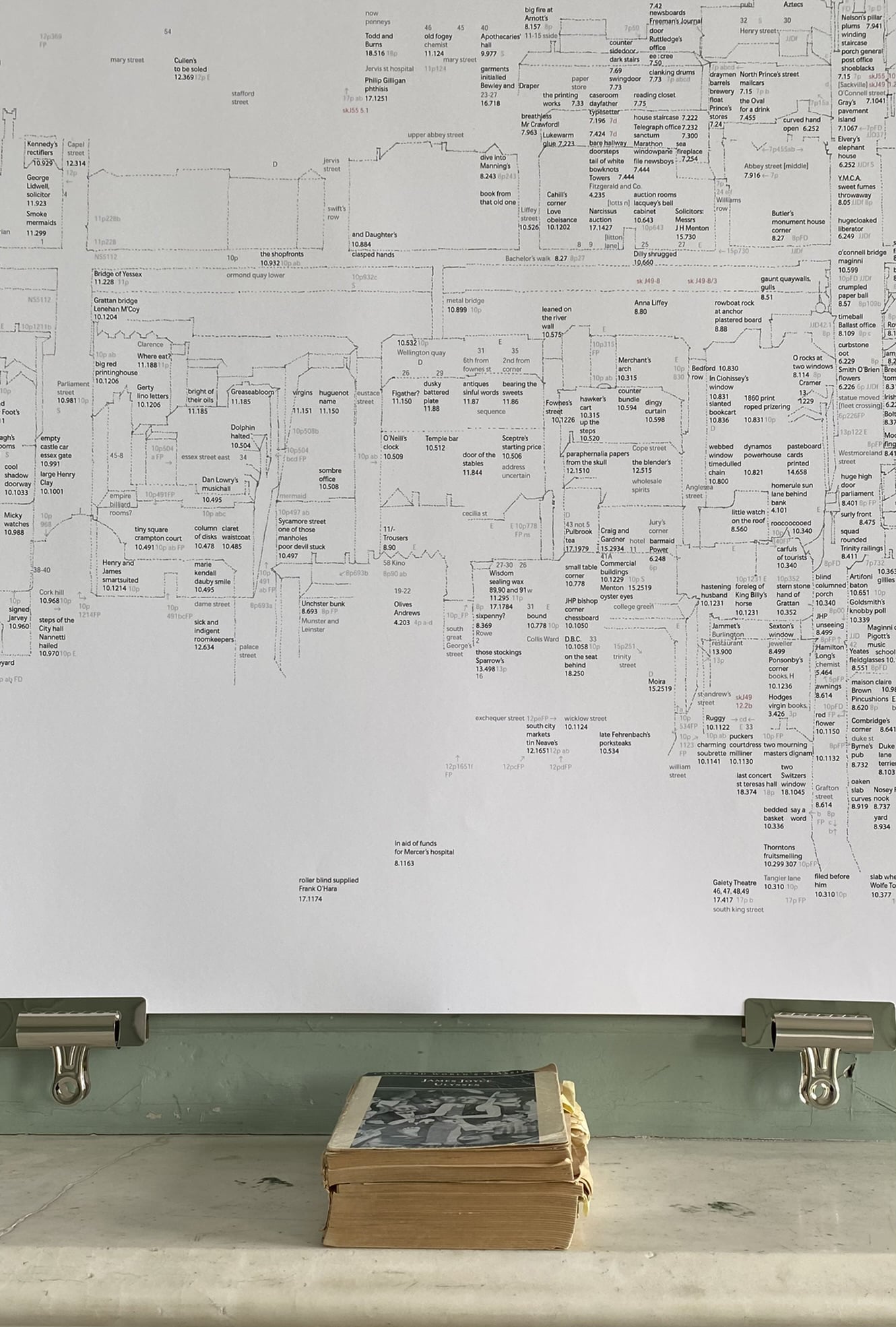

Ulysses is famous for the range of languages it deploys – from grunts and farts to the evolution of the English language (in the ‘Oxen of the Sun’ episode); but Phillipson shows that Joyce’s equally famous attention to the details of Dublin’s urban topography, buildings and furnishings are both archaeologically accurate and ‘bearers of meaning’ (Günter Bandmann). That is, the ‘epic’ finds its symbolic landscape in the everyday accoutrements of an average European city…or even below-average (Dublin was not Berlin, London, Paris or Rome). Joyce plays a game of verisimilitude, in which the actual and the fictional play off each other like the ways we are involved with our artefacts and buildings – both dumbly useful and endowed with value or importance, worth remembering, always latent in the backgrounds we make for our praxis.

As a consequence, we also discover how and when architecture makes itself evident: rarely like the everything-works-on-a-summer-afternoon renderings of ‘form-and-space’ familiar from contemporary architectural production, rather it appears in fragments, fleetingly and as the support for situations, according to which a kerbstone can attract the same respect as the interior of the National Library. Because of the way that Joyce has embodied the settings of Dublin in different modes of discourse, we acquire a sense of how the embodying conditions of a city are themselves premonitions of spoken or written or remembered or simply gestural ‘languages’ – rhythms of situational settings whose typicalities are the basis of their infinite capacity for wit or tragedy. In the opening chapter of the novel we are initiated into a symbolic tension that pervades the work, as the two modalities of our entanglement in languages – between the attempt to anchor life in architectural ordering (the Martello Tower, Dublin) and the dying-reviving horizons of the metamorphic sea (Dublin Bay, the Liffey and manifold liquids from horse piss to Holy Water).

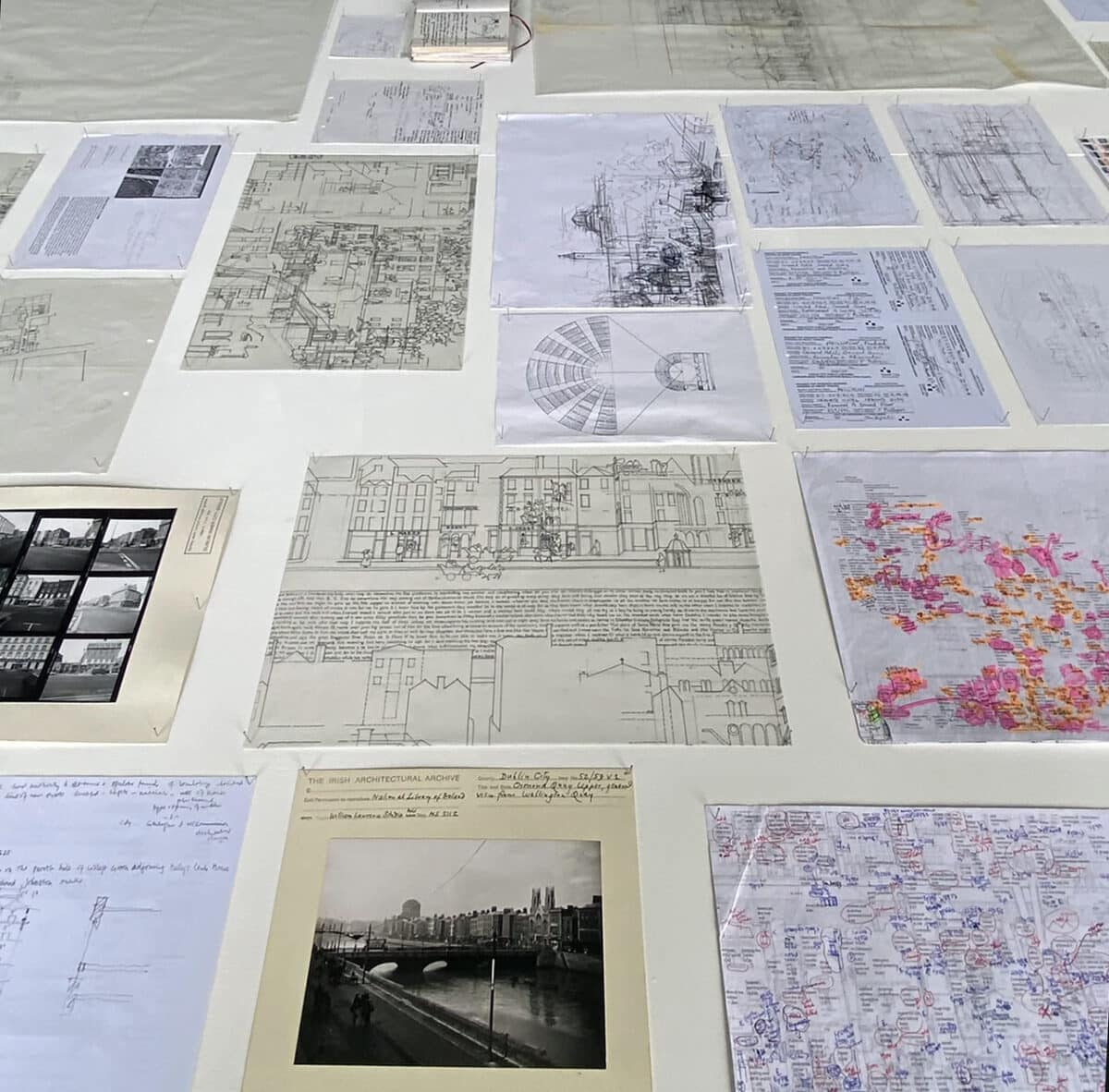

In order to bring these phenomena to visibility, Phillipson undertook several kinds of research. Firstly, he became thoroughly familiar with the manners in which urban topography, buildings and furnishings were deployed in the novel. These resonate with each other sometimes as laconic fact, sometimes as casual analogy, sometimes as symbol, sometimes just a name; and they vary in their modes of involvement from the taste of a scone to an optical triangulation across Dublin attained by the two ‘Dublin vestals’ atop Nelson’s Pillar (echoing Moses’ view of the Promised Land) in the ‘Aeolus’ episode. This research enabled him to trace out a map of the trajectories of the several characters across the day, re-enacting Joyce’s reputed use of such a map in writing the novel; and it also enabled him to begin to sketch out certain critical scenes (such as the Ormond Hotel bar, salon and restaurant in the ‘Sirens’ episode). Having this basic familiarity with both Dublin and the novel, he was able to undertake archival research – such as maps, insurance records and old photographs – to recover detailed arrangements of buildings or sequences that had been altered or lost (which was most of them, since the novel took place in parts of Dublin regarded as ripe for development).

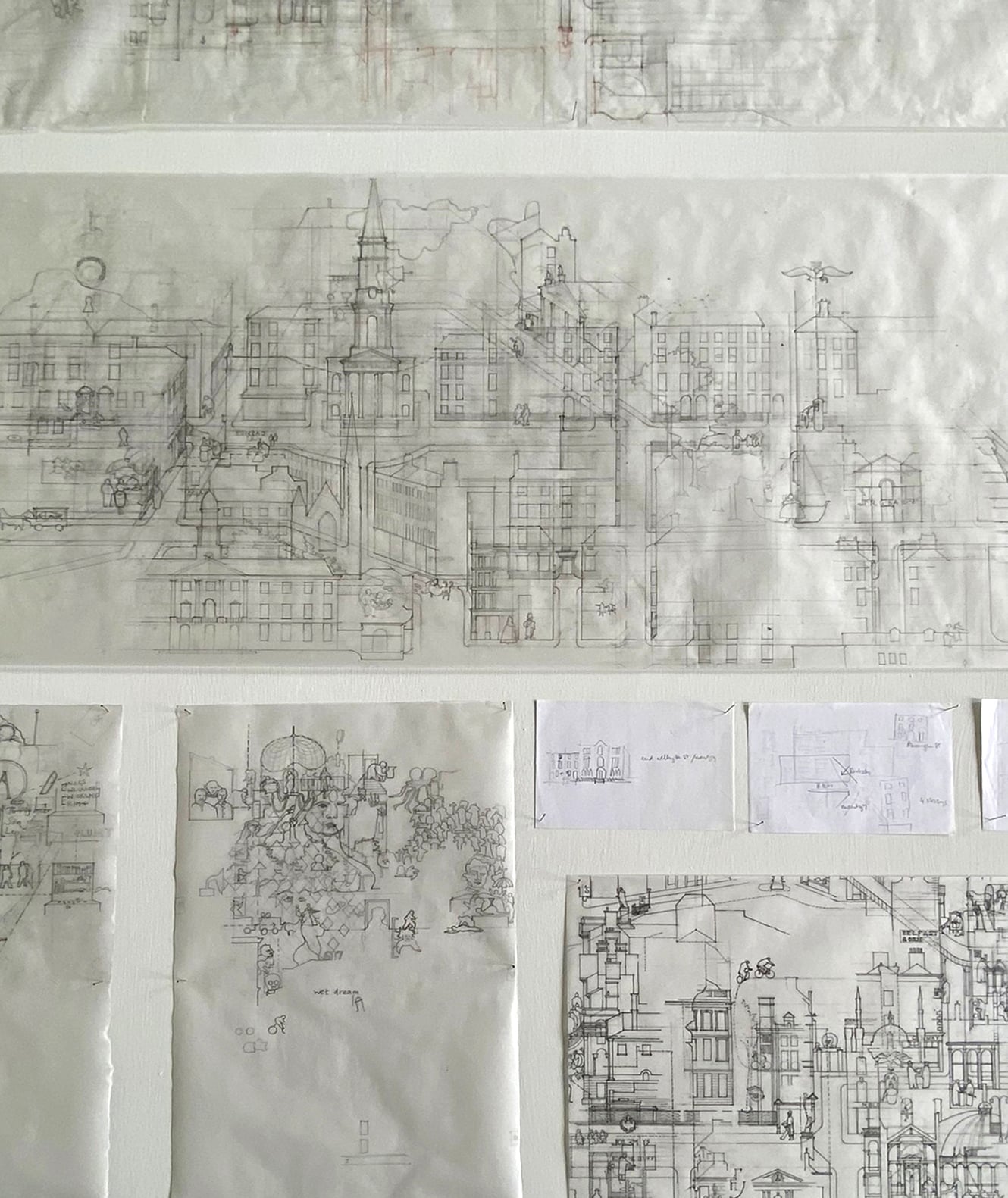

A certain amount of this kind of ‘archaeology’ had been undertaken in previous scholarship; but Phillipson’s research has been both more exhaustive and more ‘poetic’, or attentive to analogies. This is most evident in the suite of drawings in the exhibition. He discovered a species of interpretative isometric that allowed the topographic role of the sites – their distribution across Dublin – to read without losing the theatric quality of particular settings (as well as the requisite dimensions). The technique also allows for transparent or translucent walls, exposing interiors to their adjacent conditions.

Roughly speaking, he presents this material in two registers: one addresses larger sequences, whose inhabitation by the characters in the novel (e.g., a view down a street, a cluster of blokes in a pub) allows the temporal collapse of several episodes into the still image to suggest urban life in general; and the second register comprises detailed explorations of critical settings, such as the Freemason’s Journal building, the school, Bloom’s house, etc., where furniture and artefacts are more prominent. To anyone familiar with Ulysses, Phillipson’s haunting line drawings – at once both diagrammatic and evocative – reverberate with memorable passages from the text; and for those whose encounter with Ulysses was brief, the collection of drawings – displayed in the rooms of a nicely restored Georgian house – might suggest the layers of reference that are alive in a city.

Phillipson is a very talented architect as well as a superb design teacher and he is endowed with a profound intellect. The ‘research’ of which the drawings are a vehicle is not restricted to ‘archaeology’; rather this work is the necessary foundation for understanding more concretely what might be termed the spatiality of meaning, or how meaning depends upon spatial ordering. The issue here is not any particular meaning – such as the salvation promised in Le Corbusier’s ‘Radiant City’ – but rather how the grand and generous symbol of the European city arises from the memory embodied in the everyday texture of the inhabitants’ conflicts and accommodations, of their hopes and fears, of their insights and confusions. Nor is Phillipson concerned with the generalisation ‘space’ inherited from the early twentieth century. He seeks to understand something that is more bottom-up, and depends upon our modes of involvement. What is for the most part latent background is sometimes held or touched or occupied, sometimes remembered or hoped-for, sometimes a reference in the Bible, the Classics, Shakespeare, or Irish legend, history and custom, other times a label on butter-wrapping or the sound of frying kidneys, etc. Similarly we are involved sometimes casually, sometimes ritually, oftentimes in jokes or even in the Wagnerian phantasmagoria of the ‘Circe’ episode. In this respect one might speak of a topography of metaphor. Since text accommodates a diversity of reference that can lapse into simple collage when rendered visually, Phillipson’s images will eventually appear in a book he is writing, in which his twenty-year involvement with Ulysses hopes to disclose the many languages embodied in the architecture of a city.

Freddie Phillipson ‘The Ulysses Project’ is on display at the Irish Architectural Archive until 19 August 2022. The exhibition is a collaboration between Drawing Matter and the IAA. More information can be found here.

For more on The Ulysses Project, read Freddie Phillipson’s series of texts for Drawing Matter (here), and the architect interviewed by Sarah Montague for the Irish Studies Review (here).

– Sheila O'Donnell