Drawing Conversations: Letters to Clients

Le Corbusier & José Oubrerie

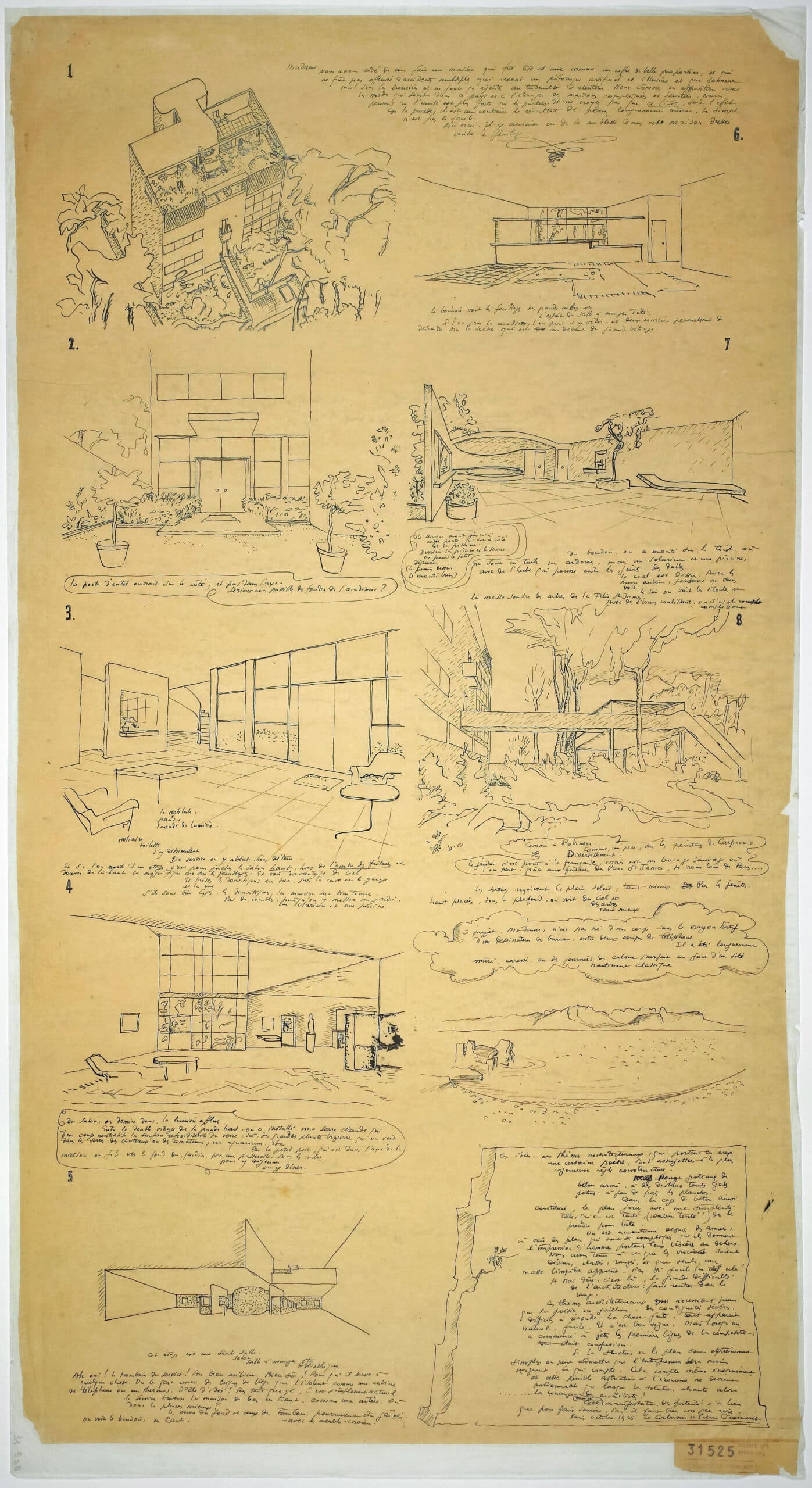

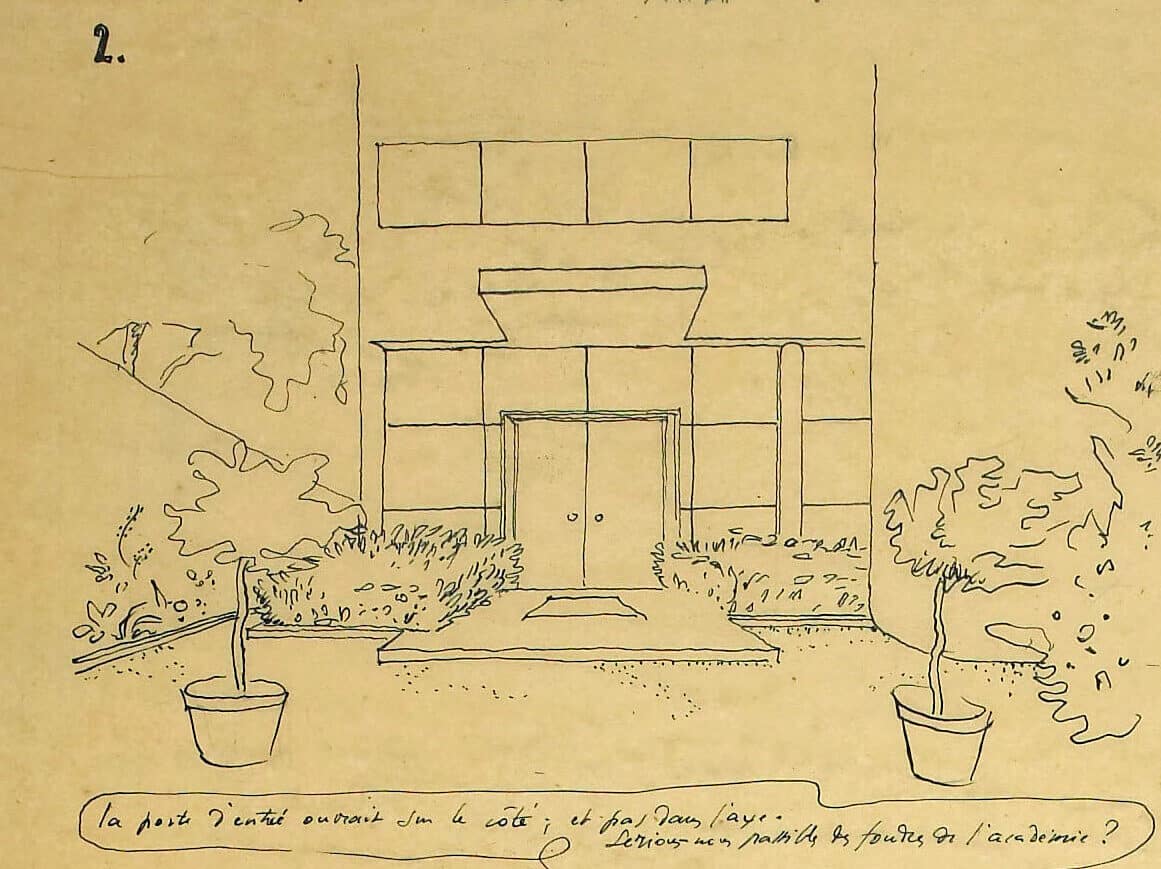

In October 1925 Le Corbusier wrote to his client Madame Meyer a remarkable letter about his proposal with Pierre Jeanneret for her villa. It combined drawings with a highly scripted text that carefully guided her through each space, from the entrance to the roof garden. Like the pioneers of early cinema, imagery was subtitled by words. Produced by the architect’s own distinctive hand, the letter was peppered with self-deprecating humour. He warned Madame Meyer about the entrance not being in the middle, ‘would this bring the wrath of the Academy down on our heads?’ and that ‘this project is not something dashed off between phone calls by some studio draughtsman’. The letter is both a flirtatious love letter from architecture, and a revealing testimony into the mechanisms and labours of realising a design. The project emerges, he tells us, out of ‘total confusion’ into ‘the initial lines of the composition’: from pure idea into the realm of the physical, and the handmade. A building only becomes possible as part of a human chain of relationships, circumstances, hopes and uncertainties, and is born into in the hands of the imperfect world of builders.

The sequence of numbered drawings set amidst the text, forms a carefully constructed journey: an episodic montage of mise-en-scène drawings framed to encapsulate the promenade architecturale. It weaves together effortlessly all the necessary domestic rituals such a client would need, with an Arcadian dreamlike series of gardens, while ‘voiced over’ with a messianic sense of modernity. This ‘drawn conversation’ from a master letter-writer is unique in its register. Le Corbusier ‘spoke’ firstly always through drawing. It was his essential shorthand to transcribe and recompose the world around him, and through which to deploy architecture as an open and continuous conversation with the world. His published sketchbooks reveal the intensity of this process more expansively as do his frequent letters to his mother where the conversation is laid bare to reveal both his daily struggles in architecture, with that of a devoted son seeking his mother’s approval and affections. [1]

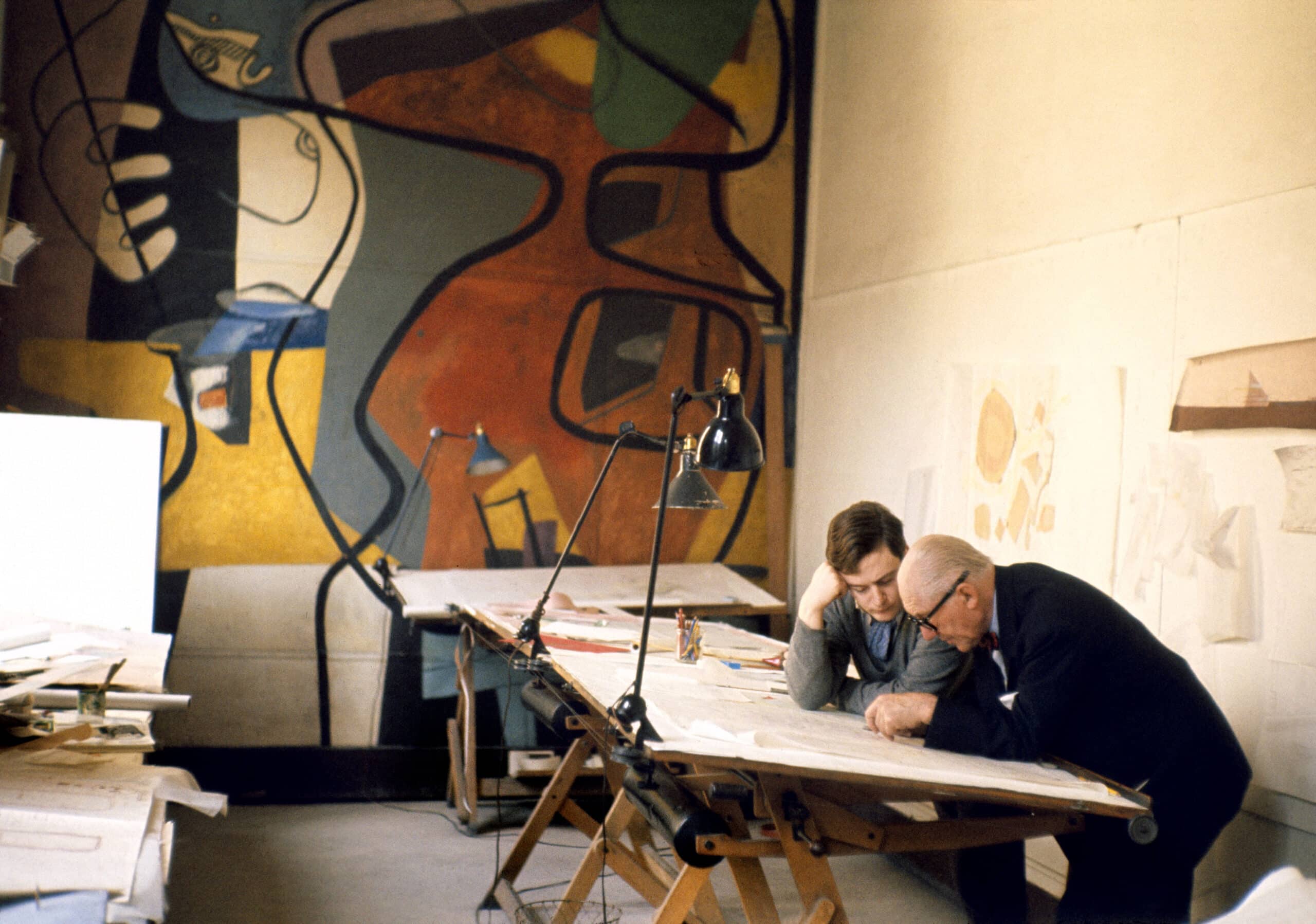

The later years of Le Corbusier’s atelier in the Rue de Sèvres were wholly dependent on a number of remarkable assistants with whom Le Corbusier worked extremely closely. Using his shorthand of drawing and words, miniature ‘letters’ of instruction and epiphanies on paper, were left for each collaborator at their drawing tables each day, usually after long hours in his painter’s studio in Nungesser-et-Coli, or on the return from one of his travels. They would allow a dialogue and understanding that short circuits the usual working methods and discussions of a practice. Le Corbusier, as has been discussed by Judi Loach [2] ran his studio more like a unique laboratory than any traditional practice. Between the relative silence of the magician and his apprentices, there was an encoded sense of deep understanding embedded through these exchanges of ‘letters’ as signatures of his thought process and specific project directions, delivered to the initiates that could read his handwriting (drawing).

One of the most prominent and outstanding of these collaborators was José Oubrerie, who would go on to build a remarkable career after Le Corbusier’s death and the closing of the studio. He is known not least for the completion of the Firminy church, for which he had been the original project architect, and for his work and teaching which has been widely recognised and honoured. He has taught in Paris, Milan, Venice, and a number of American universities such as The Cooper Union, Columbia and Kentucky.

In Oubrerie’s ‘Letter to a Client’ from 1986, there are echoes of his exchanges with that of his master. Somehow connected by the movement and understanding of different hands that have worked and ‘spoken’ together. There is a similarity in the directness of the drawings, and the informal beauty of the words. It speaks to us of a sense of continuity in the work of the Paris atelier, and Oubrerie’s own distinctive identity and approach. Seen together the letters reveal the familiar conversations, frustrations and predicaments, faced by every architect. In both letters the drawings are intensely alive and beautiful in animating each architect’s intentions.

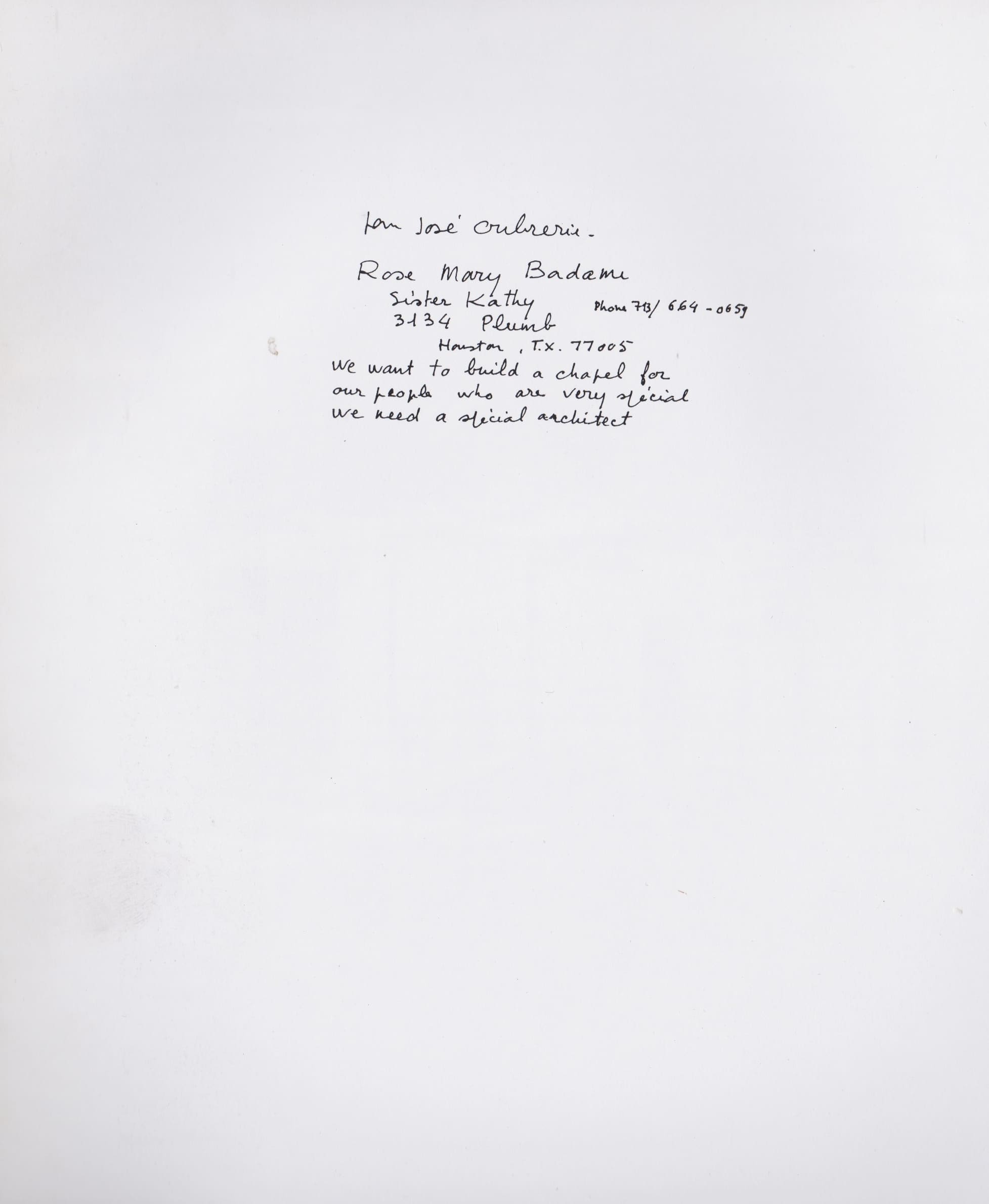

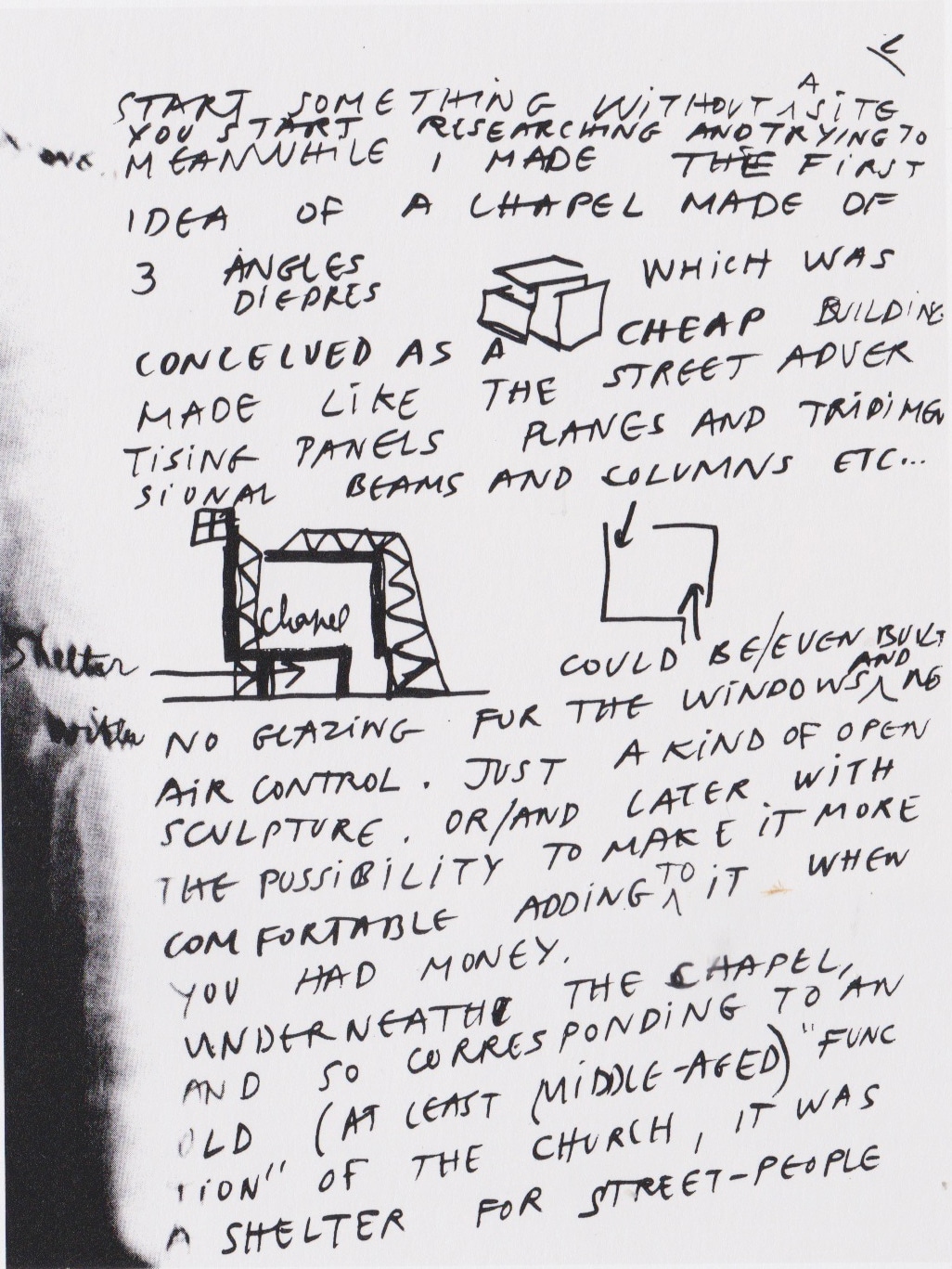

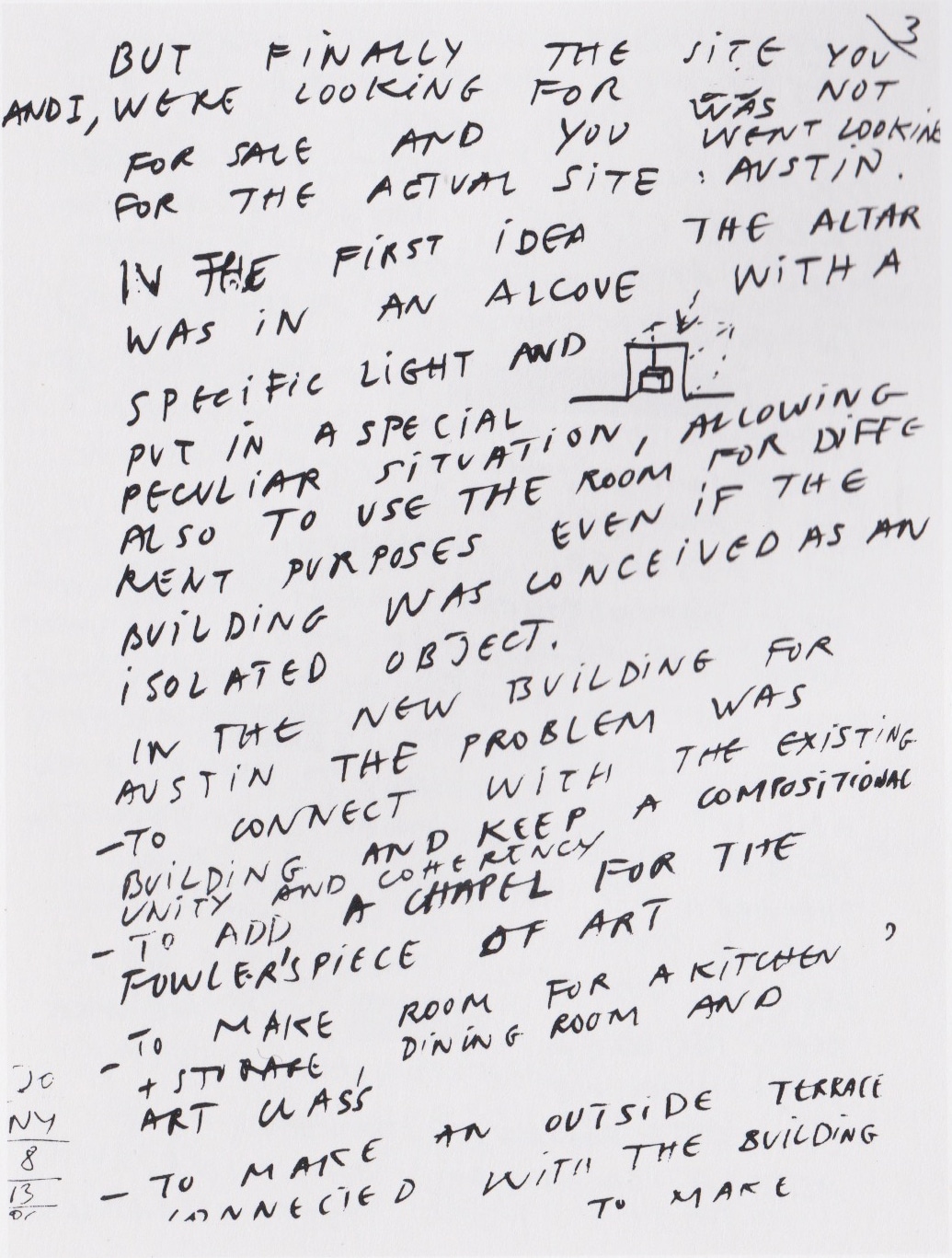

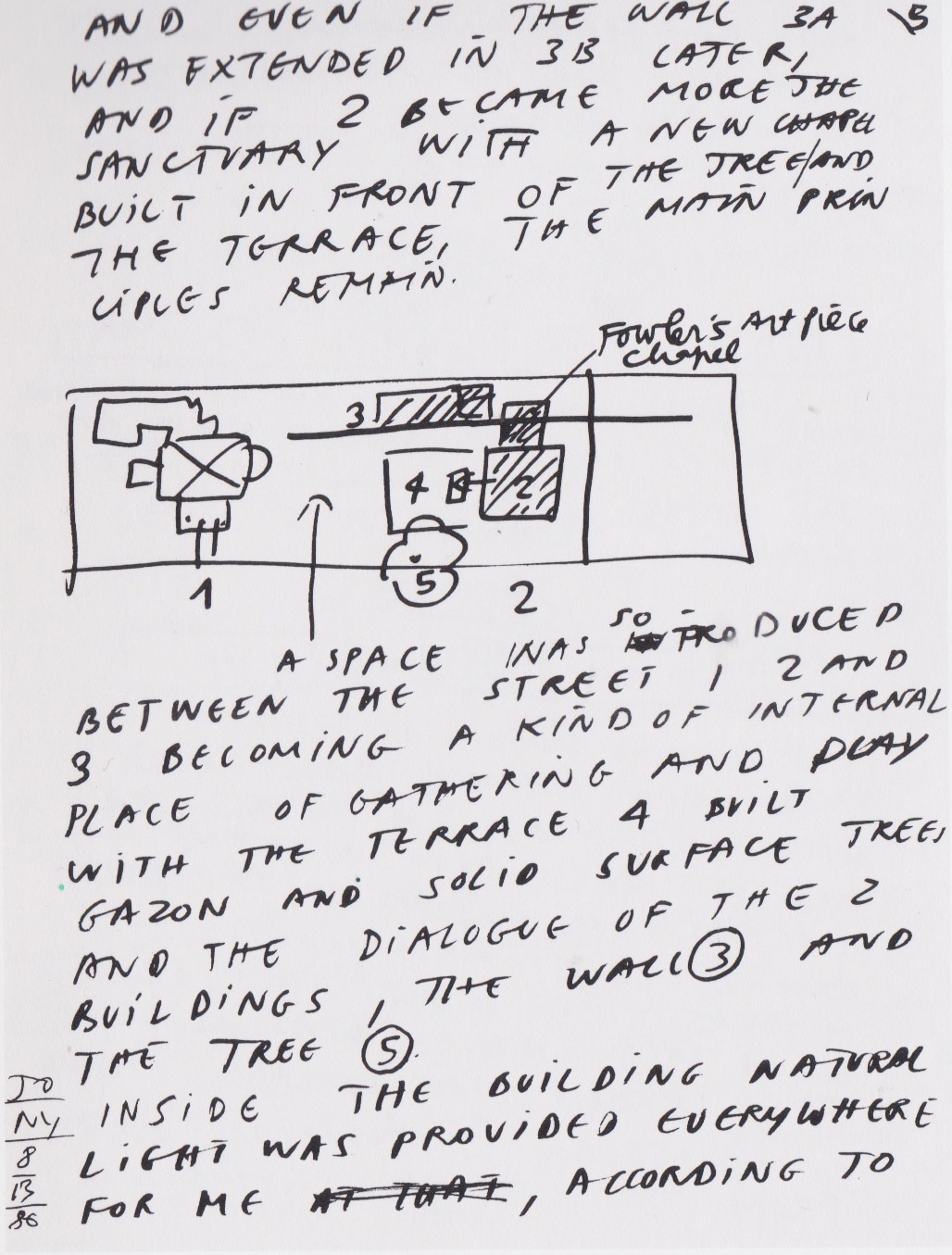

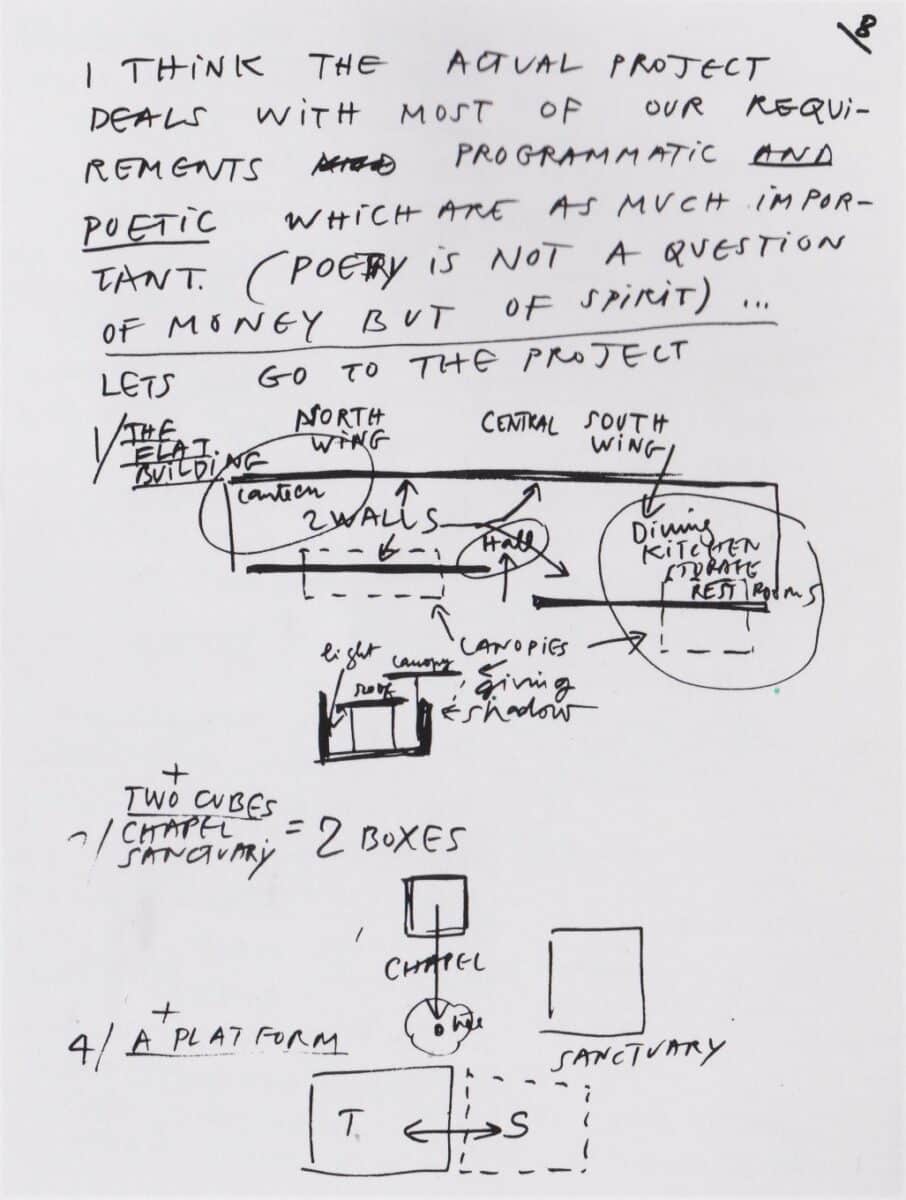

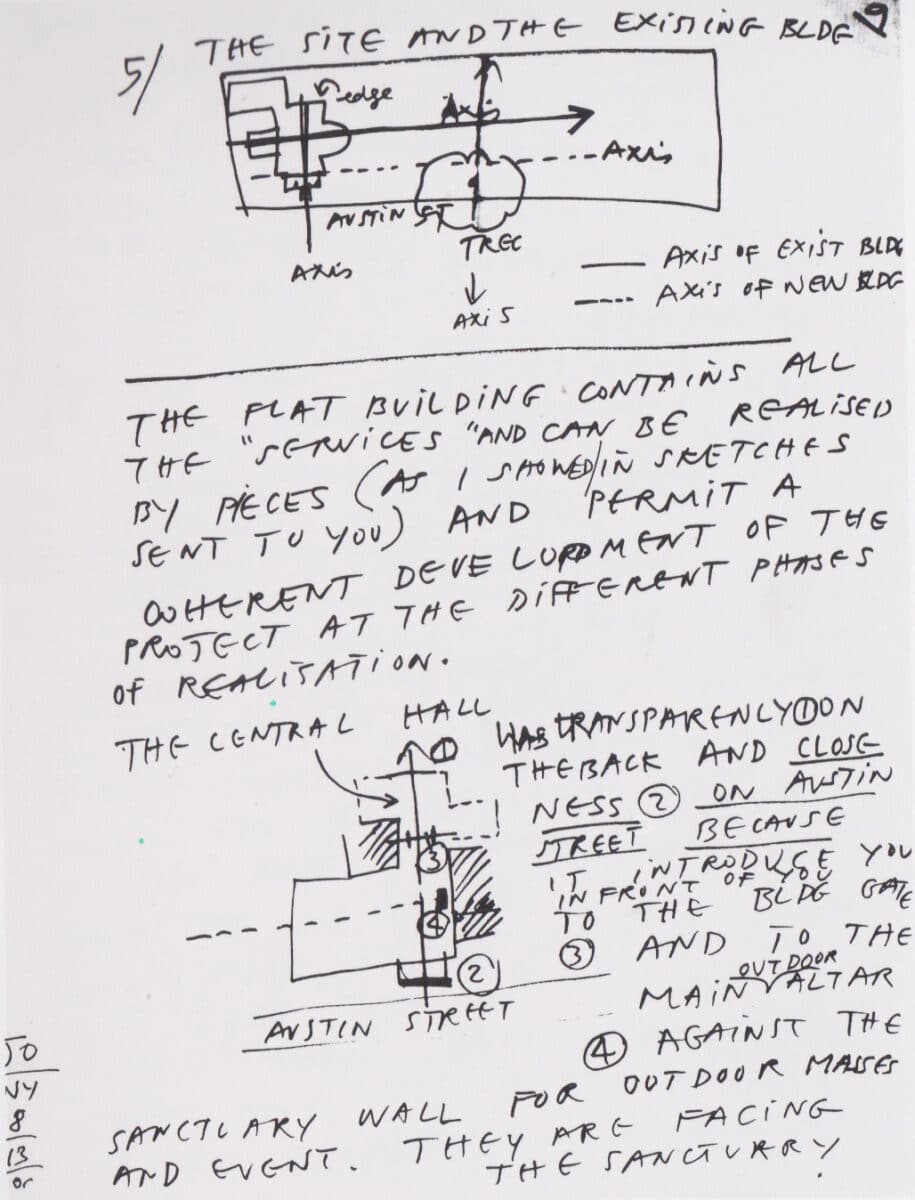

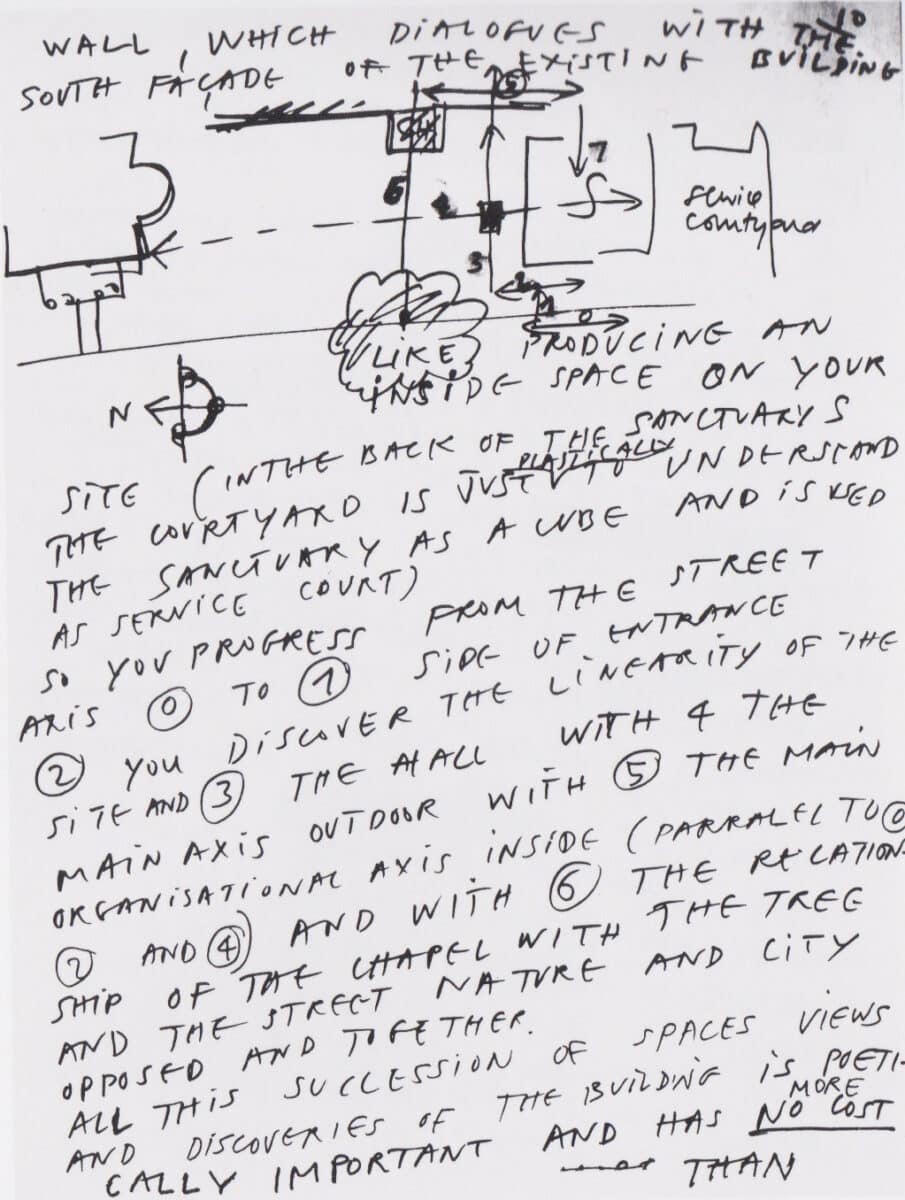

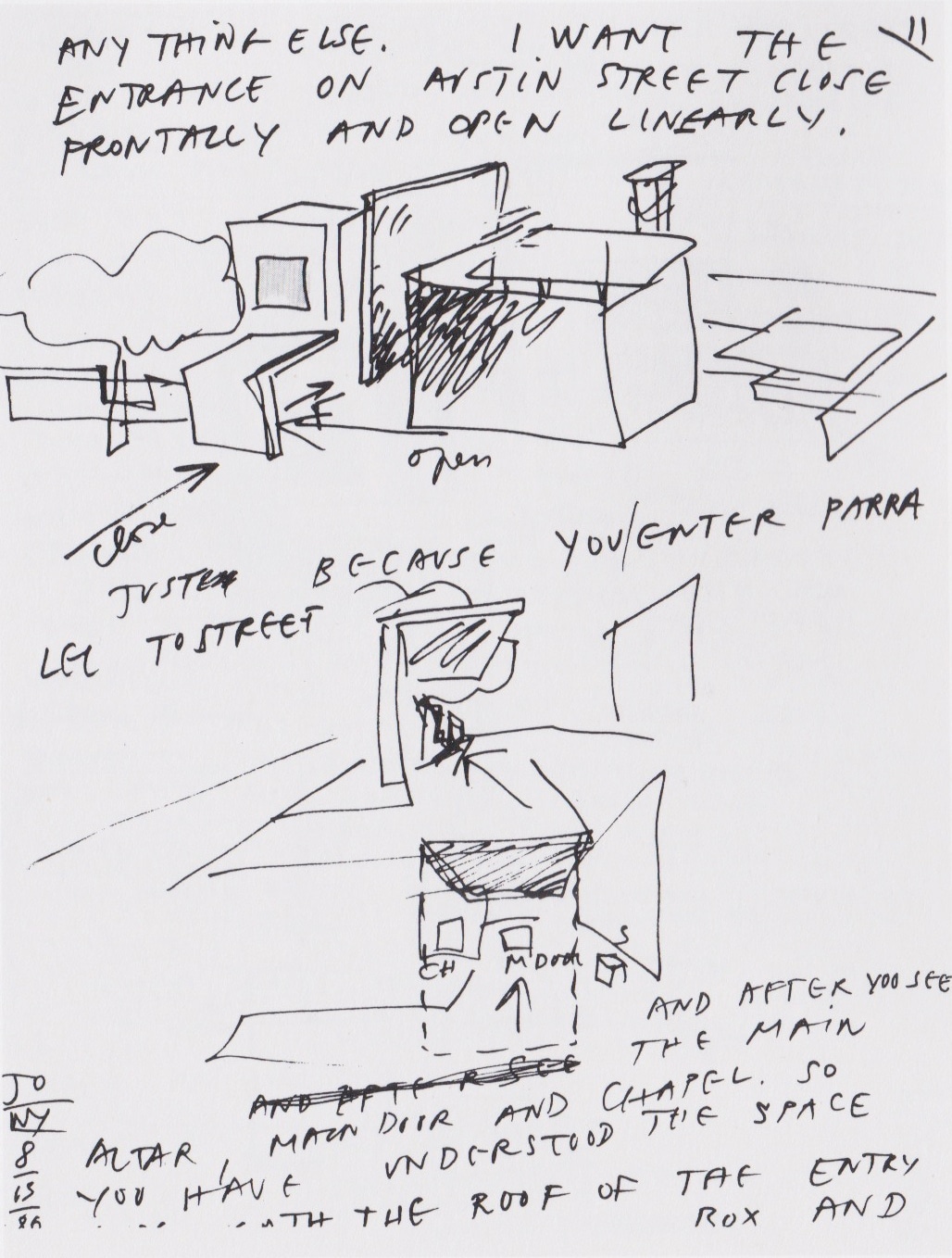

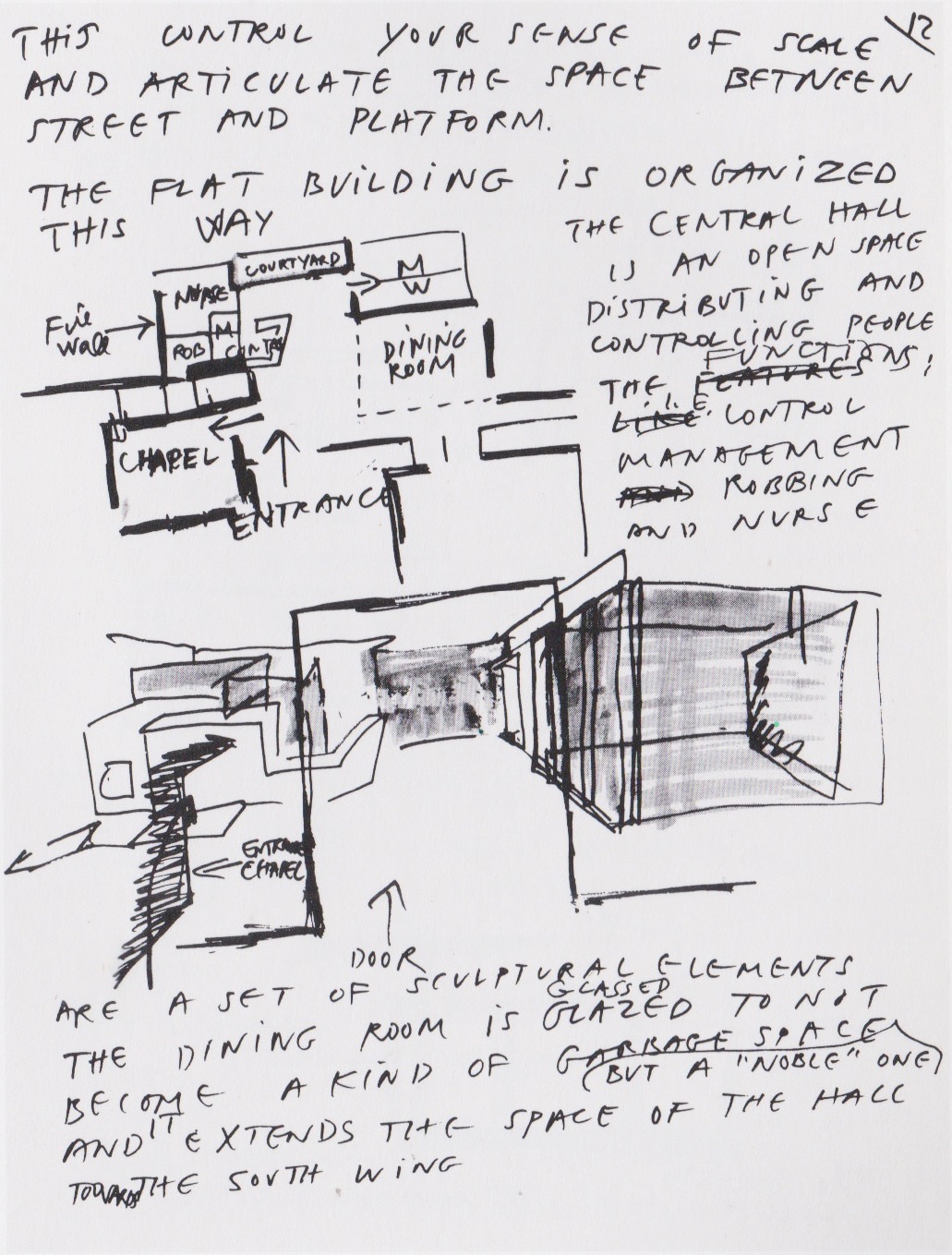

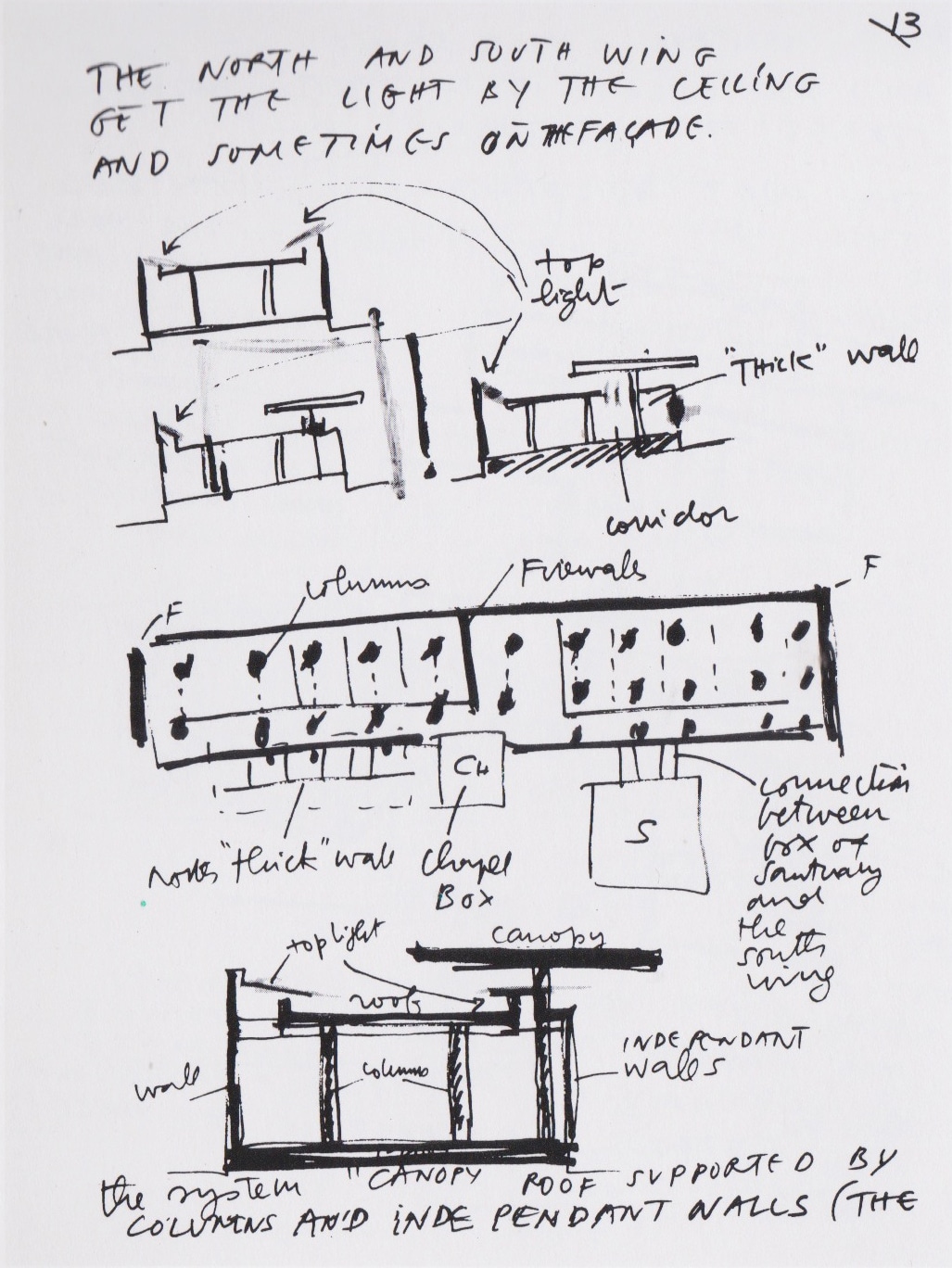

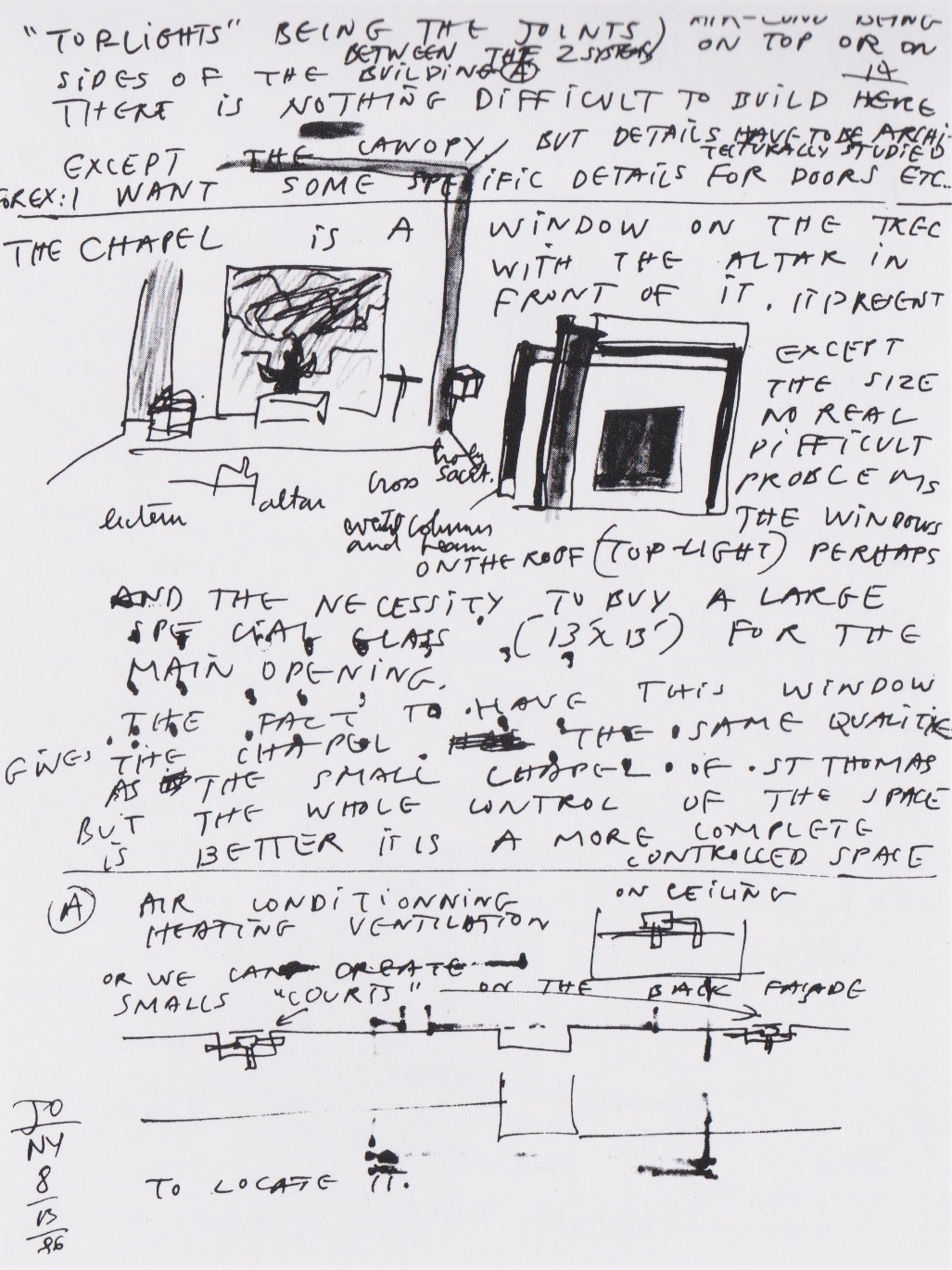

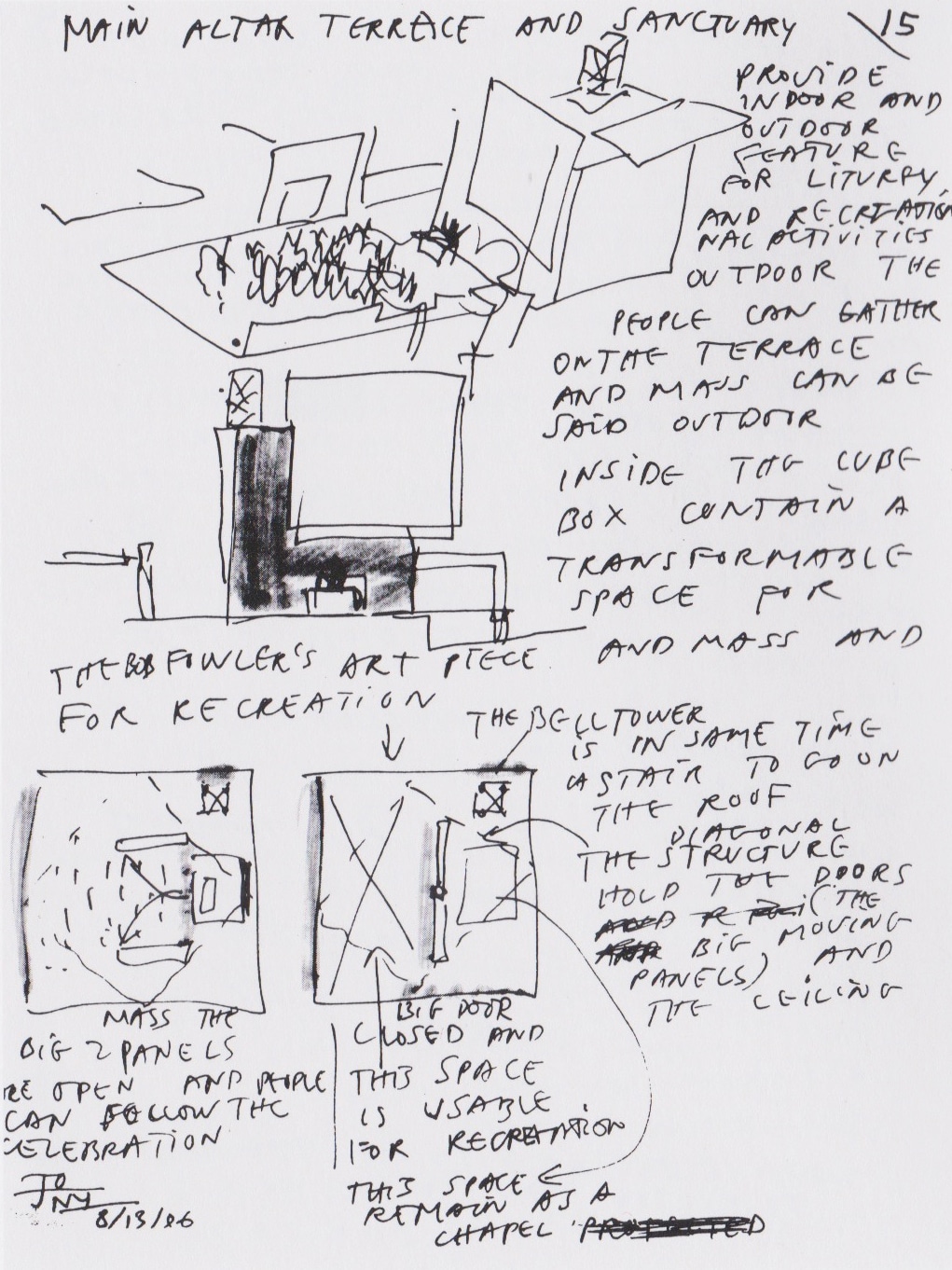

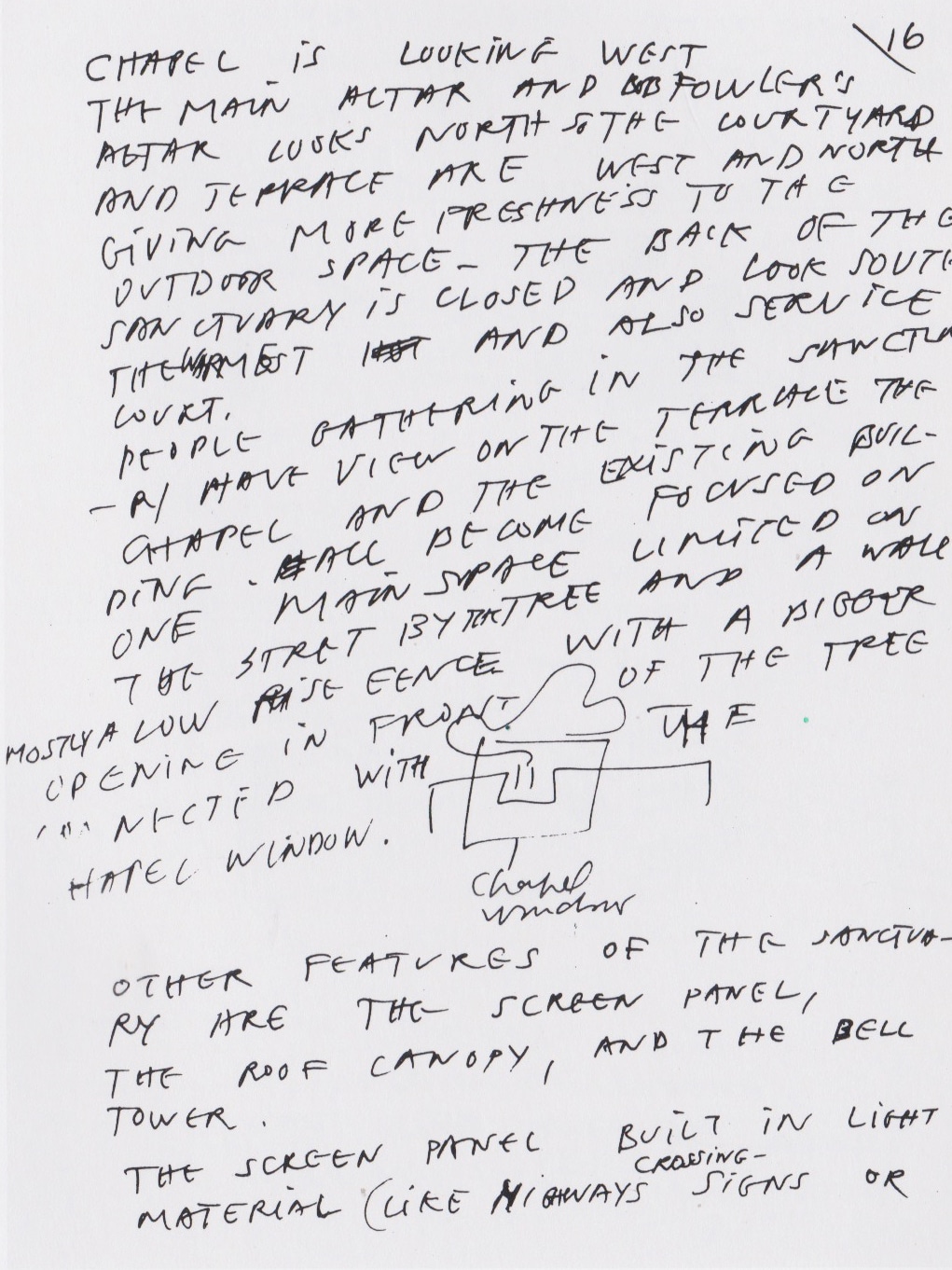

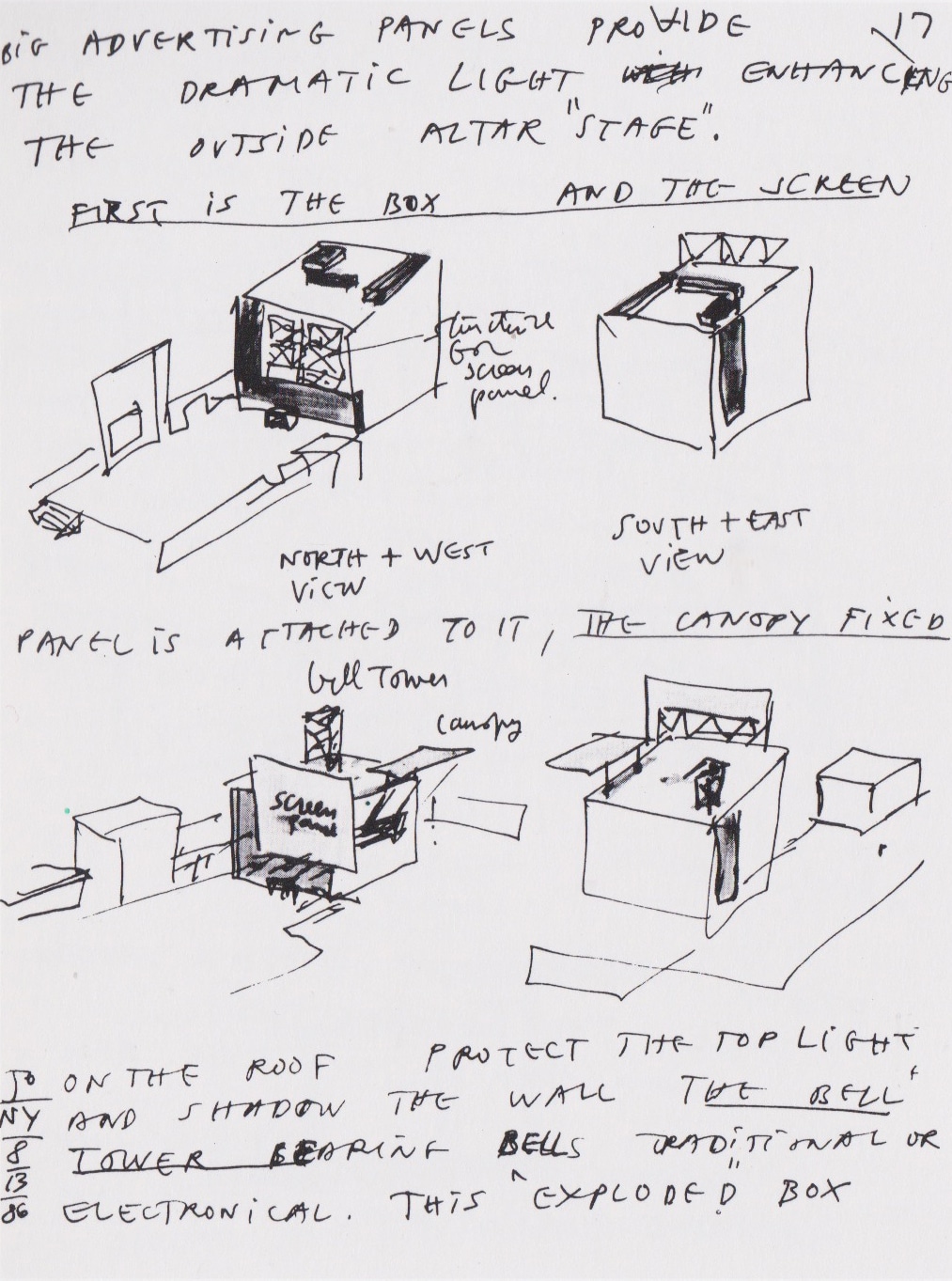

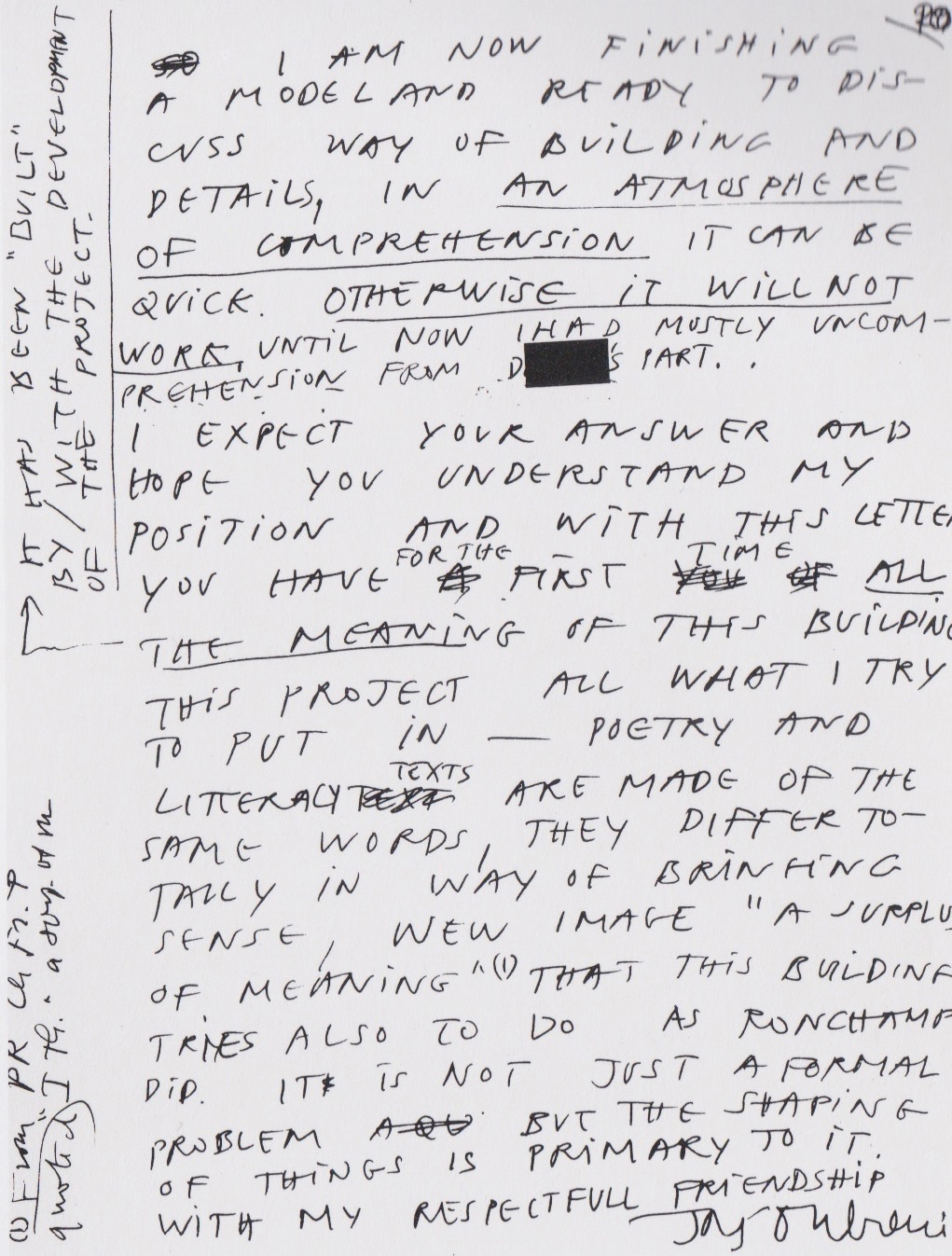

In Oubrerie’s letter the drawings are like enlarged figural letters set within the capitalised energetic flow of his handwriting. Passionate and direct, at times confessional and reflective, the words are continually hopeful and strategically optimistic. Oubrerie has a painter’s eye (in which he originally trained) that informs every step, and perhaps especially attuned him to working with Le Corbusier. This time we are taken on a more open, and more inconclusive journey, than that of the Villa Meyer letter. The love letter this time is a humble one: to a client who approached the architect with a vague sense of doing something special and to make a church for the street people of her community. Not a rich private client, but one with a vague memory of Ronchamp’s spiritual beauty, and the need to make something special and memorable.

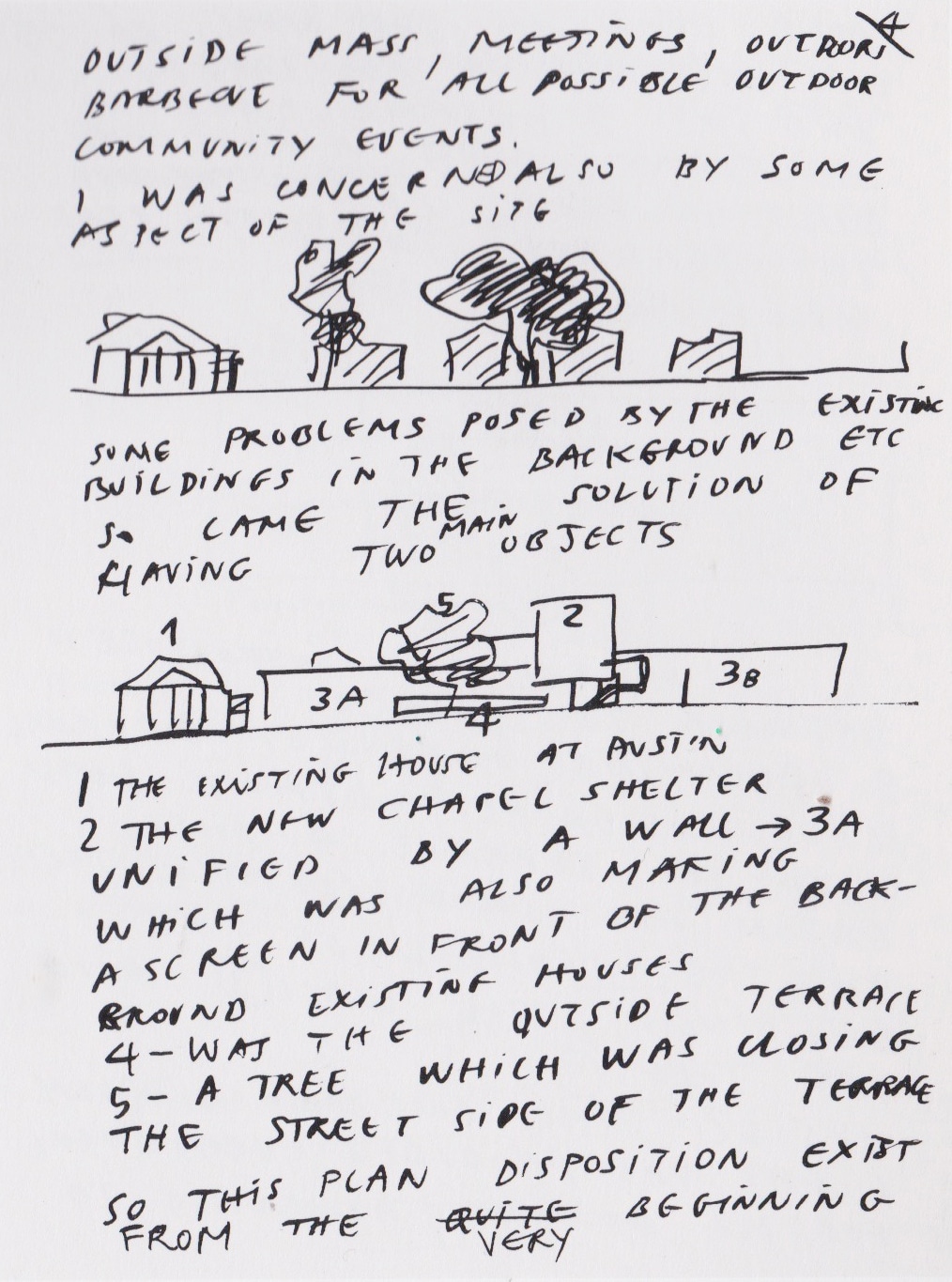

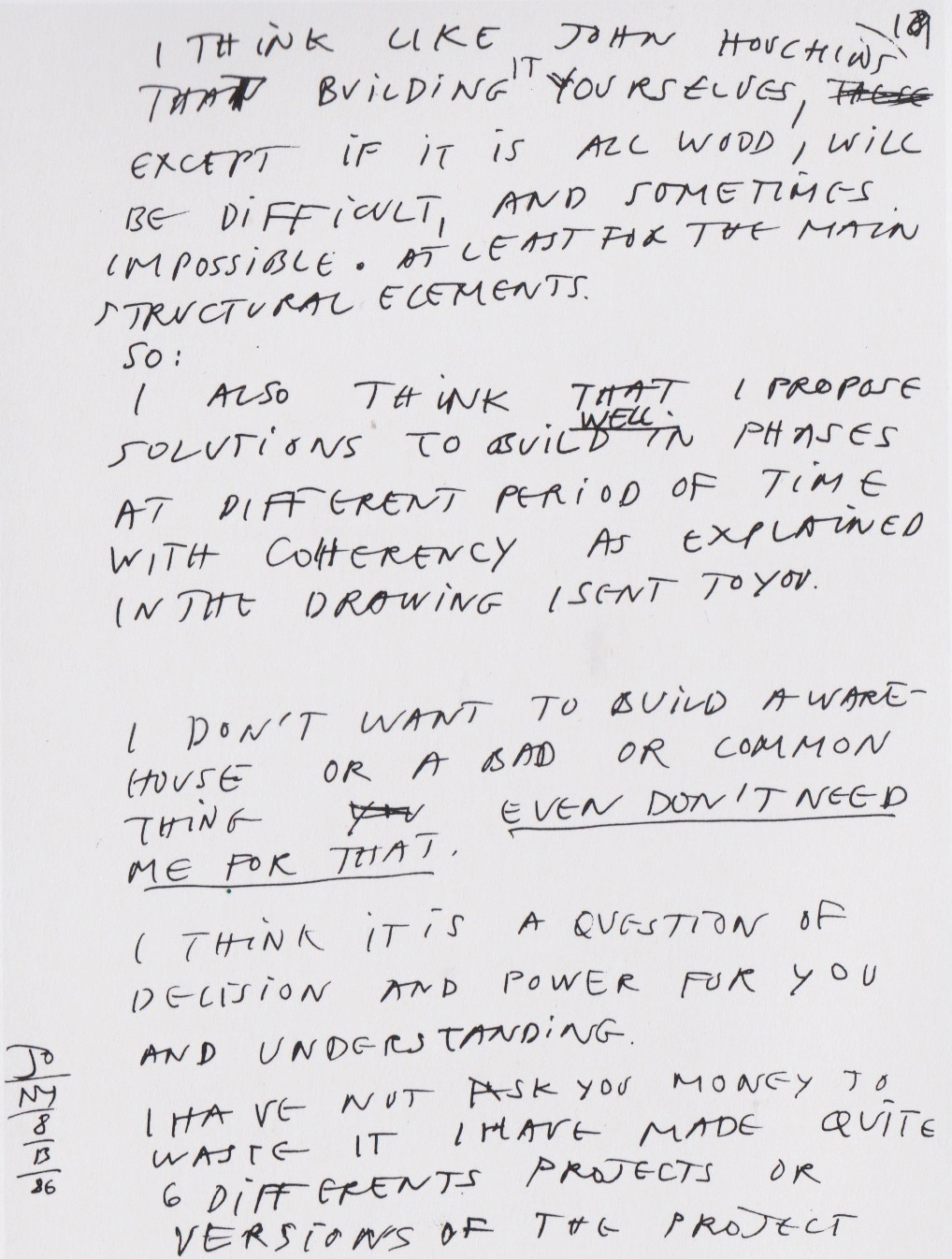

Ideas emerge slowly in Oubrerie’s letter. The drawings are like tiny flowers opening from within the text. First, a simple sequence of planes elevated to provide shelter below, with an exoskeleton structure open to the elements and affordable to build over time when funds become available. Small moves and ideas gather pace in the letter such as the initial thought for the altar in an alcove with special light. Maybe this recalls the extraordinary Venice Hospital project and Church that Oubrerie collaborated on after Le Corbusier’s death? We witness the charting of ideas. The opening of a simple box to light. Was that not the intention in the Villa Meyer? The clarity of Oubrerie’s drawings become painter-like ideograms that are charged and vibrant. More woven into the sequences of words than in Le Corbusier’s letter, the drawings appear exactly when needed, and animate the architect’s thoughts with remarkable clarity. Every line is essential. Each labelling system clear and vivid.

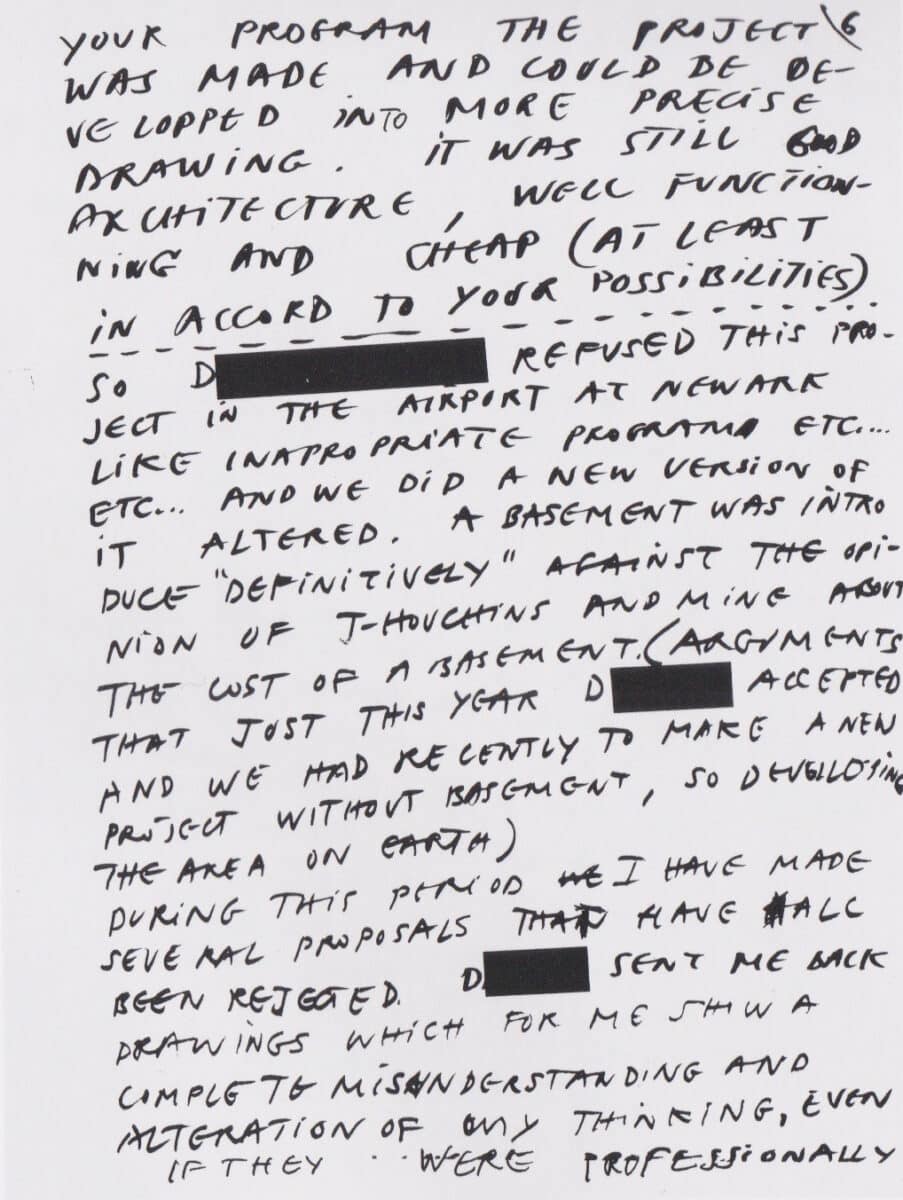

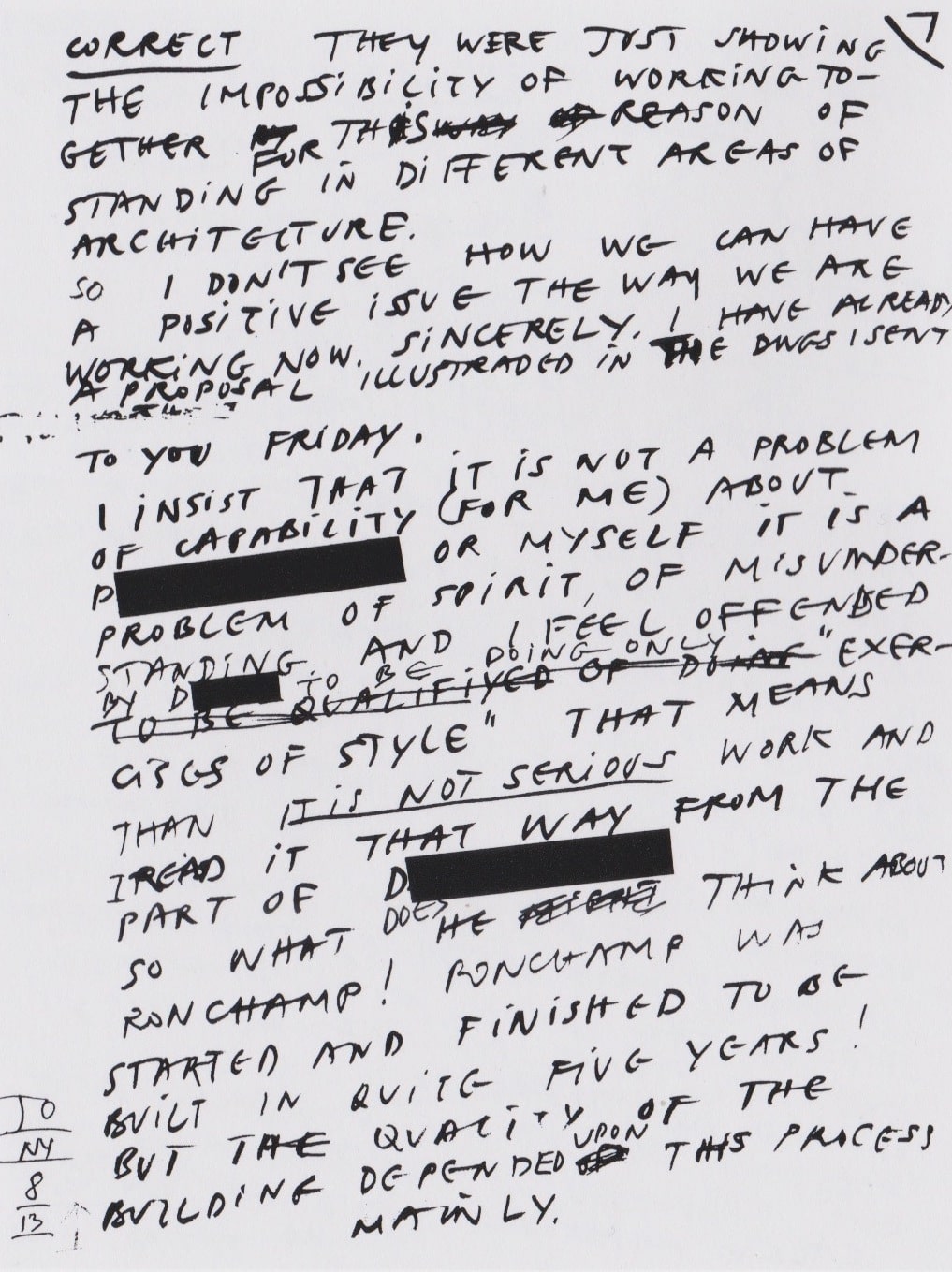

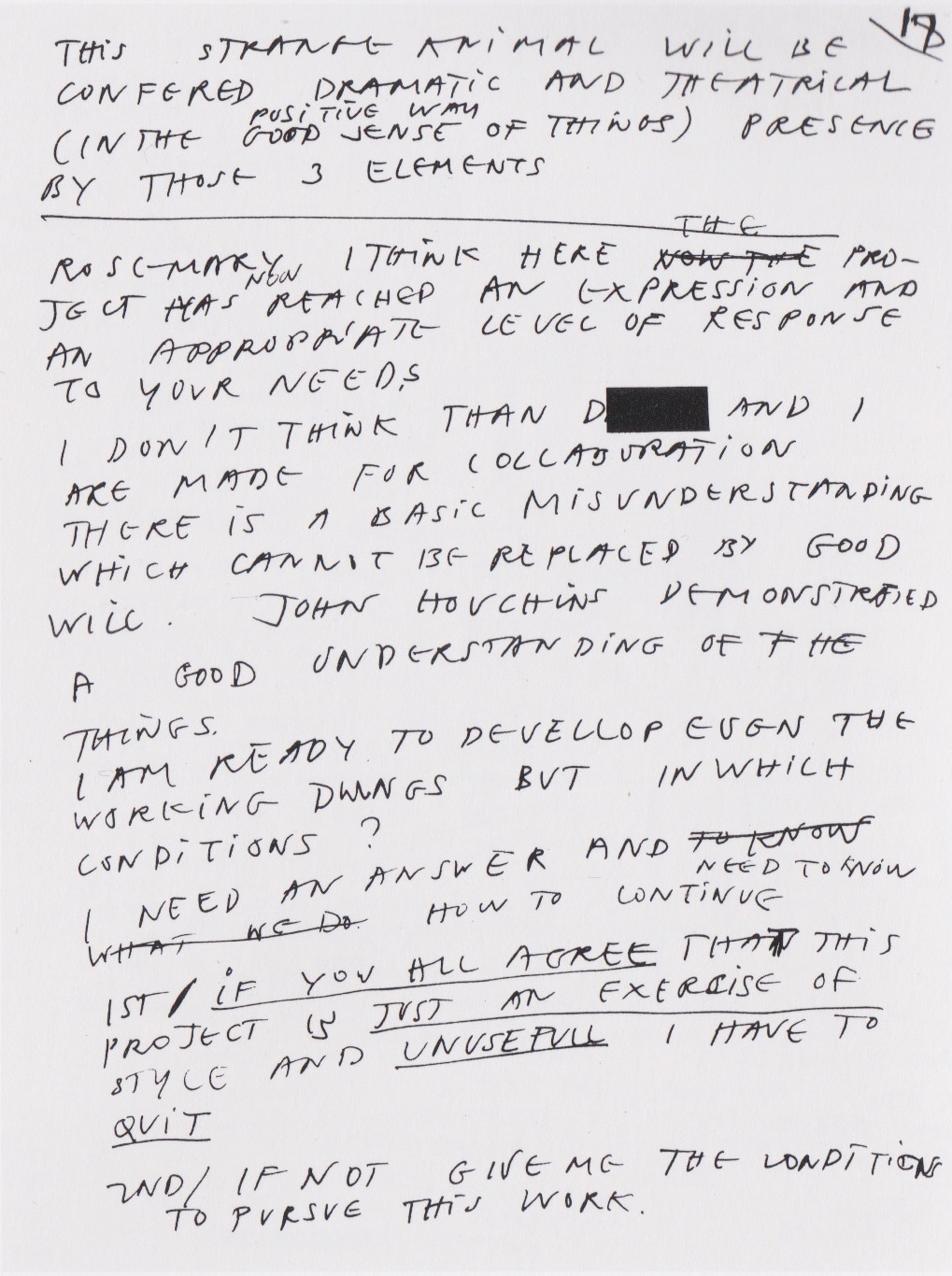

Occasionally you sense the drawing back of breath. A pause. A line is drawn under a proposal. A name appears blanked out after the letter D. The first sign of resistance and disharmony. A suggested collaboration is recognised as being impossible and full of misunderstanding. Each time something is offered anew.

The beauty of this long letter lies in its ability to draw out the unfolding of Oubrerie’s ideas, and to draw us deeper and deeper into them. Oubrerie is a natural teacher and the letter is in a way the perfect studio lesson. His approach maintains the continuous slow burn of the profession’s essential optimism. We momentarily inhabit with him across the pages, the pain and pleasures, the twists and turns of fate, and the implications of circumstances and decisions, that can either enable or disable a project. One moment buoyant with ideas, the next questioning: ‘is it time to quit?’ Confessional, doubtful and childlike optimism.

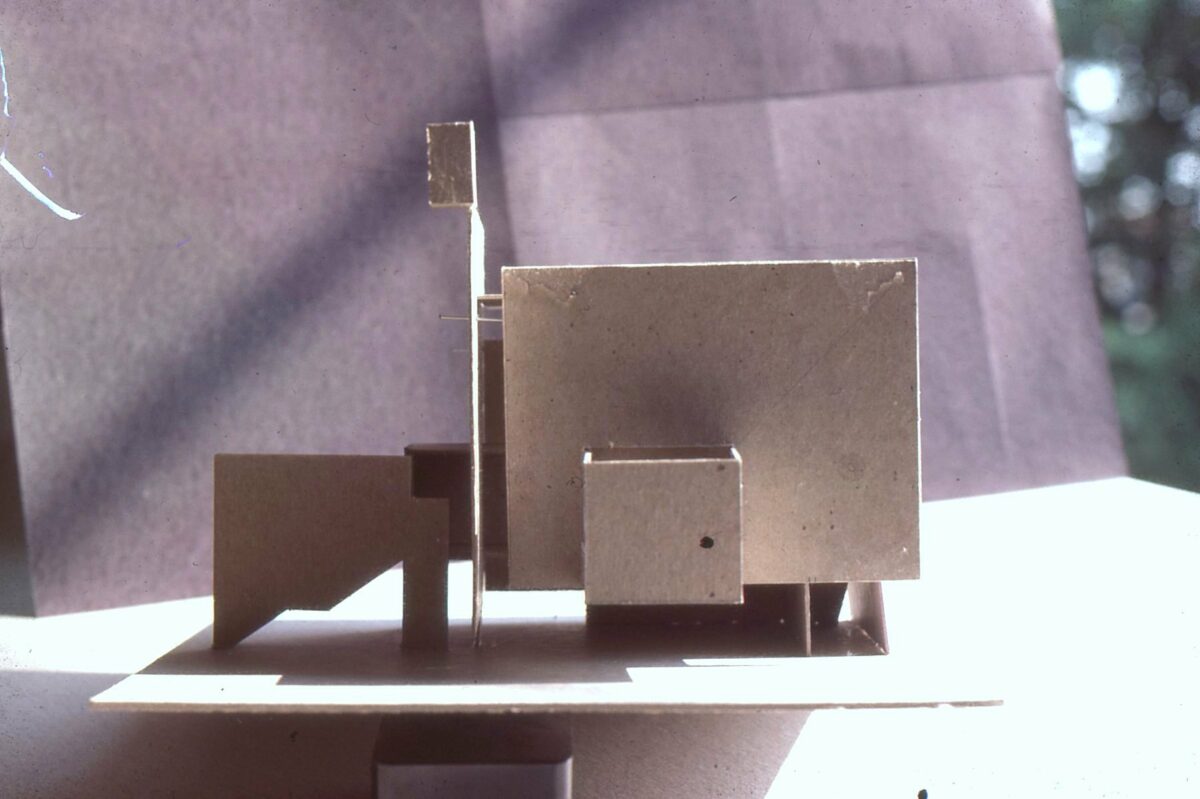

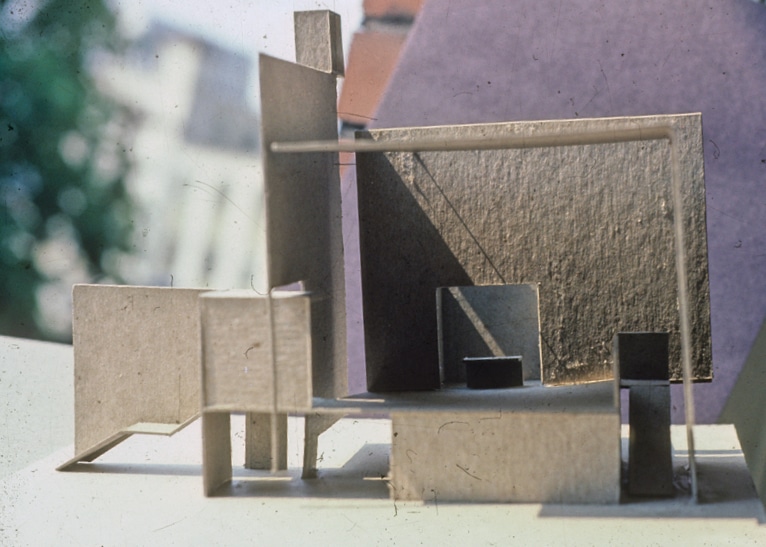

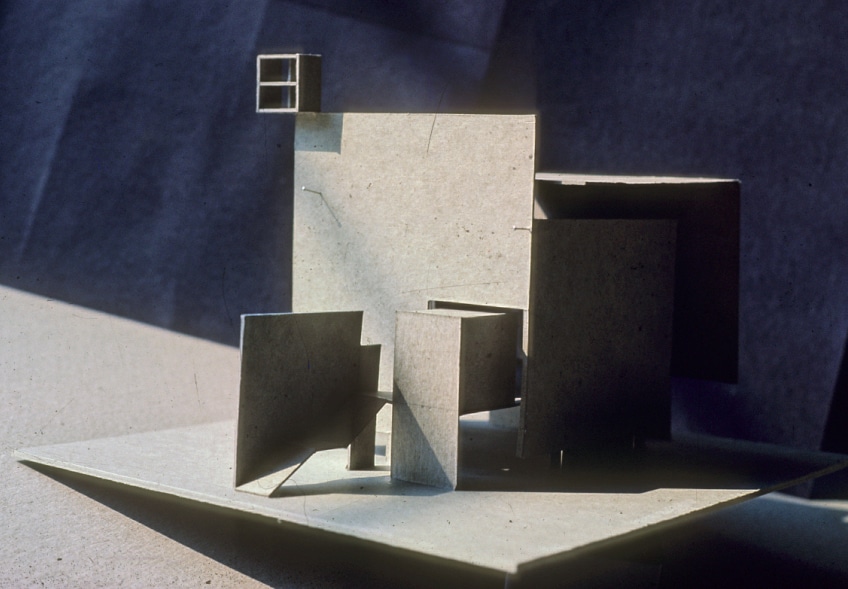

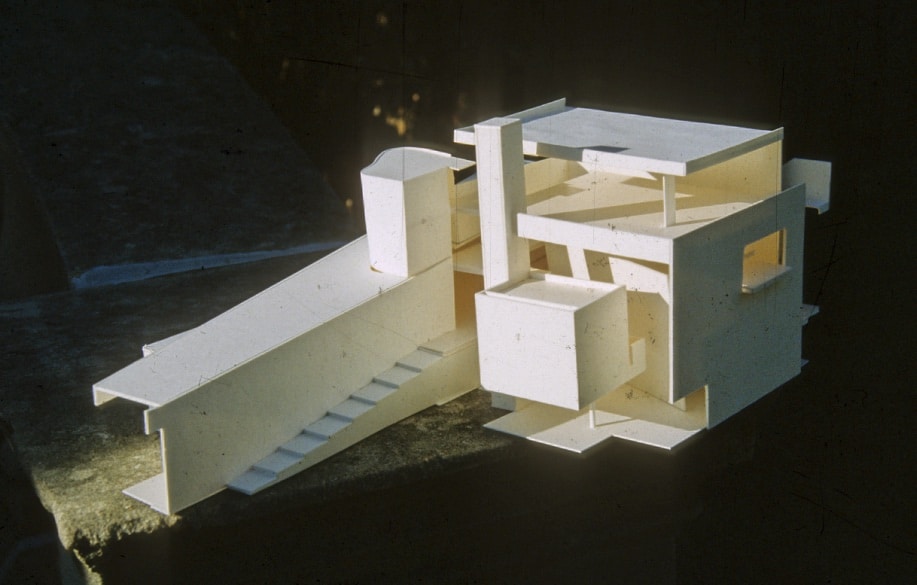

There are lessons in this letter, not just for students in the documenting of an idea, but life lessons, by a masterful architect. I first read it the year I graduated when it was published in Architecture and Body by Rizzoli. It reached out to me very directly by being given covert privilege to read what is essentially a private letter. It enriches you with a sense of architecture’s fundamental values, while using the simplest tools available. It safeguards and treasures a sense of what Le Corbusier called the most important dimension of life, poetry, and which runs through everything that is written, drawn and made by Oubrerie. The final model that accompanies the letter is a beautiful testament to his modus operandi. Open and not precious while beautifully potent in ideas. It manifests the ethos of how models were used in the Rue de Sèvres, something that should be seen as invaluable to our over dependence on the digital.

As the phenomena of the hand-written letter begins to disappear, José Oubrerie’s ‘Letter to a Client’ marks a certain passing too of the architectural love letter. There has always been a certain predicament in such letters. As Barthes suggested in A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments ‘the lover’s fatal identity is shaped in that they live in the complication of supposing to be simultaneously loved, and at the same time abandoned.’ [3]

In his letter of 1925 to Madame Meyer Le Corbusier ends by warning ‘after all one has to laugh now and then’ as if to diffuse and prophesy the inevitable outcome of his own letter and project. A Homeric laughter echoes through the pages of these two letters. Both combine the lover’s intertwined optimism and betrayal of the architect’s intent in the outcome. Both remain, as only letters on a page.

Paul Clarke is Professor of Architectural Design at the Belfast School of Architecture and the Built Environment

Notes

- The sketchbooks were published in four volumes from 1981–1982: Volume 1: 1914–1948 (Thames & Hudson); Volume 2: 1950–1954 (Thames & Hudson); Volume 3: 1954–57 (AF MIT Press); Volume 4: 1957–64 (AF MIT Press). Preface written by Andre Wogenscky, an introduction by Maurice Besset and detail notes by Francoise de Franclieu. The extraordinary range of notes and drawings in these notebooks illustrate in detail not only Le Corbusier’s ideas for buildings, paintings, observations of the world around him, and chart his continuous travels, but they also reveal very private moments of reflections on his life, his changing health, and the books that bring him continual inspiration such as by Cervantes and Rabelais. The notebooks warrant considerable study in parallel with Le Corbusier’s works, books and letters.

- Judi Loach, ‘Studio as Laboratory’, The Architectural Review 1079 (January 1987), 73–77. Based on a series of interviews, this reveals the unique nature of the studio in the Rue de Sèvres over different periods of time, including remarkably in 1959 when Le Corbusier fired (if this is the term that can be used to describe having the locks changed) three of his senior collaborators, when they were on holiday. The dynamics of the studio was constantly changing in terms of numbers and related directly to the scale of the projects underway, but also in relation to Le Corbusier’s patterns of working and his changing affinities with his assistants. The last phase of the studio, in which José Oubrerie worked, is perhaps one of the least documented, outwith the reflections of individual assistants, but is one of the most remarkable phases of its creativity and which awaits further research.

- Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments, translated by Richard Howard (Penguin Books, 1990).