Through a Glass Darkly

This text was first published in DMJournal No.1: The Geological Imagination (2023). Print copies of the Journal, and subscriptions for the first three issues, are now available through our online bookshop. We are currently accepting abstracts for the third issue of DMJournal. Find more information here.

Since Burckhardt’s discovery of Petra in 1812, Europeans and Americans had struggled for words to describe what they found there; their preferred language—of Gilpin or Baron Taylor—proved itself inadequate again and again. And the painters scarcely fared better. They remained stuck somehow at Tintern, or in the Lake District, with the limited range of their travelling watercolour palettes, and all immediacy lost once they were back in front of their easels in London. Much of the written record of both writers and painters is instead consumed by accounts of tribal politics, arguments with the ‘fellahs’, or the discomfort of travel.

It is Edward Lear—a writer and a painter—who makes the problem of description central to the account of his visit, over two days, in 1858. As he moves towards the city from Hebron, he seems to nod with studied irony towards the problem for himself and his readers:

‘April 9. At length we started. A walk over the South Downs from Lewes to Brighton would give a fairly correct idea of the general forms of the rolling scenery intersected with smooth dales through which we passed’

And then, after three more days of travel, on his ‘wicked’ camel:

‘…after passing the solitary column which stands sentinel-like over the heaps of ruin around, and reaching the open space whence the whole area of the old city and the vast eastern cliff are fully seen, I own to having been more delighted and astonished than I had ever been by any spectacle. Not that at the first glance the extent and magnificence of this enchanted valley can be appreciated: this, its surprising brilliancy and variety of colour, and its incredible amount of detail, forbid. But after a while, when the eyes have taken in the undulating slopes terraced and cut and covered with immense foundations and innumerable stones, ruined temples, broken pillars and capitals, and the lengthened masses of masonry on each side of the river that runs from east to west through the whole wady, down to the very edge of the water, and when the sight has rested on the towering western cliffs below Mount Hor, crowded with perforated tombs, and on the astonishing array of wonders carved in the opposite face of the great eastern cliff, then the impression that both pen and pencil in travellers’ hands have fallen infinitely short of a true portrait of Petra deepens into certainty.

Nor is this the fault of either artist or author. The attraction arising from the singular mixture of architectural labour with the wildest extravagances of nature,—the excessive and almost terrible feeling of loneliness in the very midst of scenes so plainly telling of a past glory and a race of days long gone, the vivid contrast of the countless fragments of ruin, basement, foundation, wall, and scattered stone, with the bright green of the vegetation, and the rainbow hues of rock and cliff,—the dark openings of the hollow tombs on every side,—the white river bed and its clear stream, edged with superb scarlet-tufted blossom of oleander alternating with groups of white-flowered bloom,—all these combine to form a magical condensation of beauty and wonder which the ablest pen or pencil has no chance of conveying to the eye or mind. Even if all the myriad details of loveliness in colour, and all the visible witchery of wild nature and human toil could be rendered exactly, who could reproduce the dead silence and strange feeling of solitude which are among the chief characteristics of this enchanted region? What art could give the star-bright flitting of the wild dove and rock-partridge through the oleander-gloom, or the sound of the clear river rushing among the ruins of the fallen city?

Petra must remain a wonder which can only be understood by visiting the place itself, and memory is the only mirror in which its whole resemblance can faithfully live. I felt, “I have found a new world—but my art is helpless to recall it to others, or to represent it to those who have never seen it.” Yet, as the enthusiastic foreigner said to the angry huntsman who asked if he meant to catch the fox,—I will try. [1]’

Lear leaves early the following day, defeated in a negotiation with hostile locals who accuse him and his party of trespass.

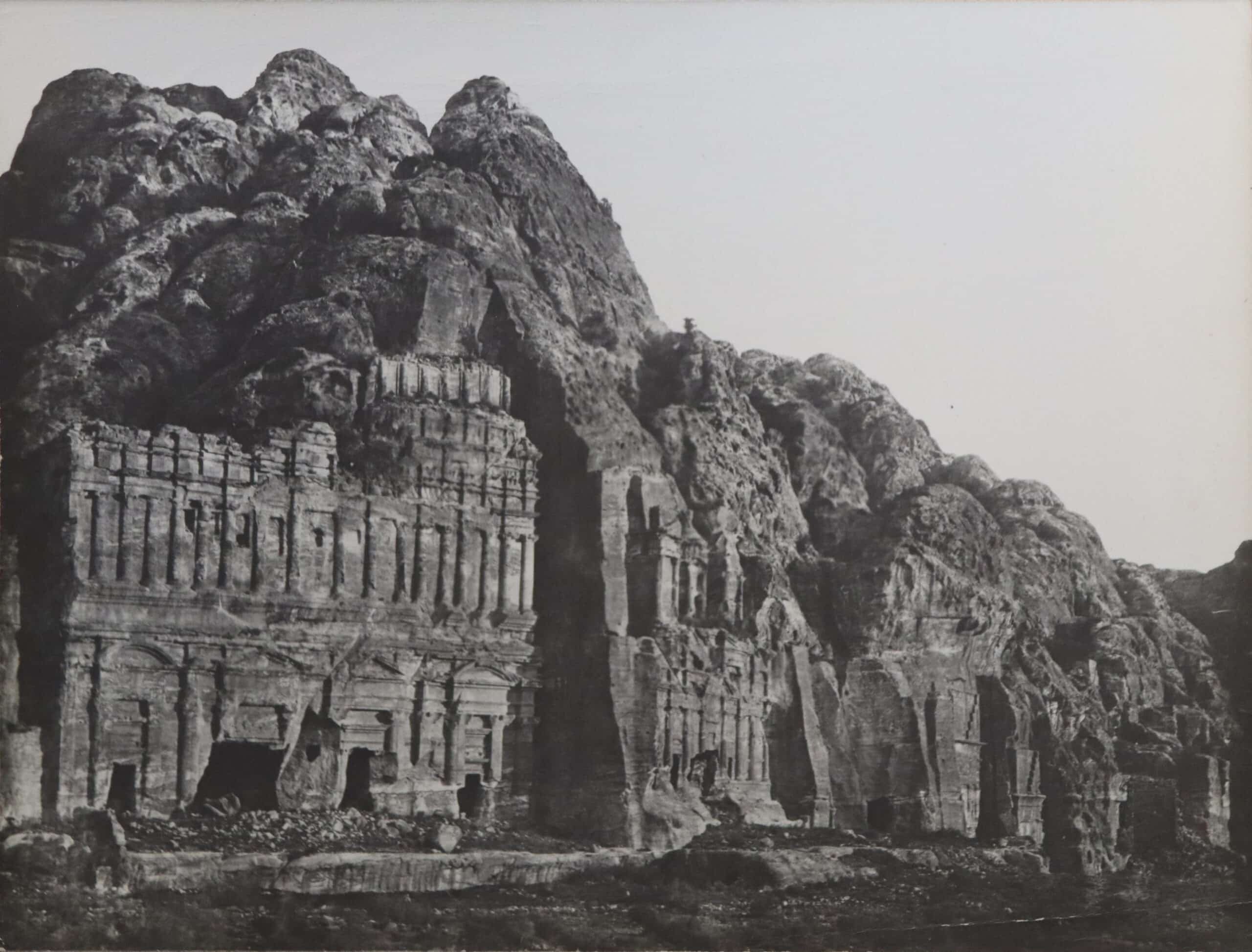

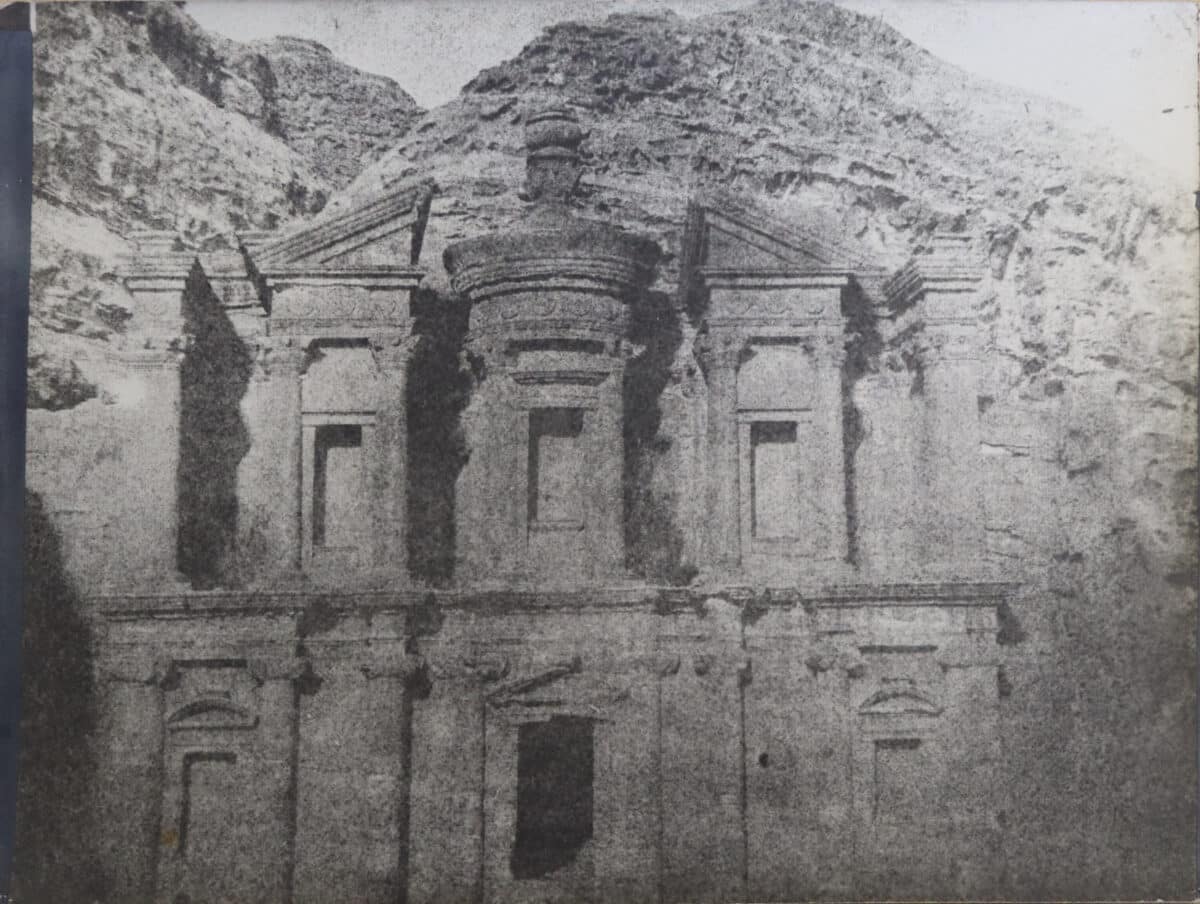

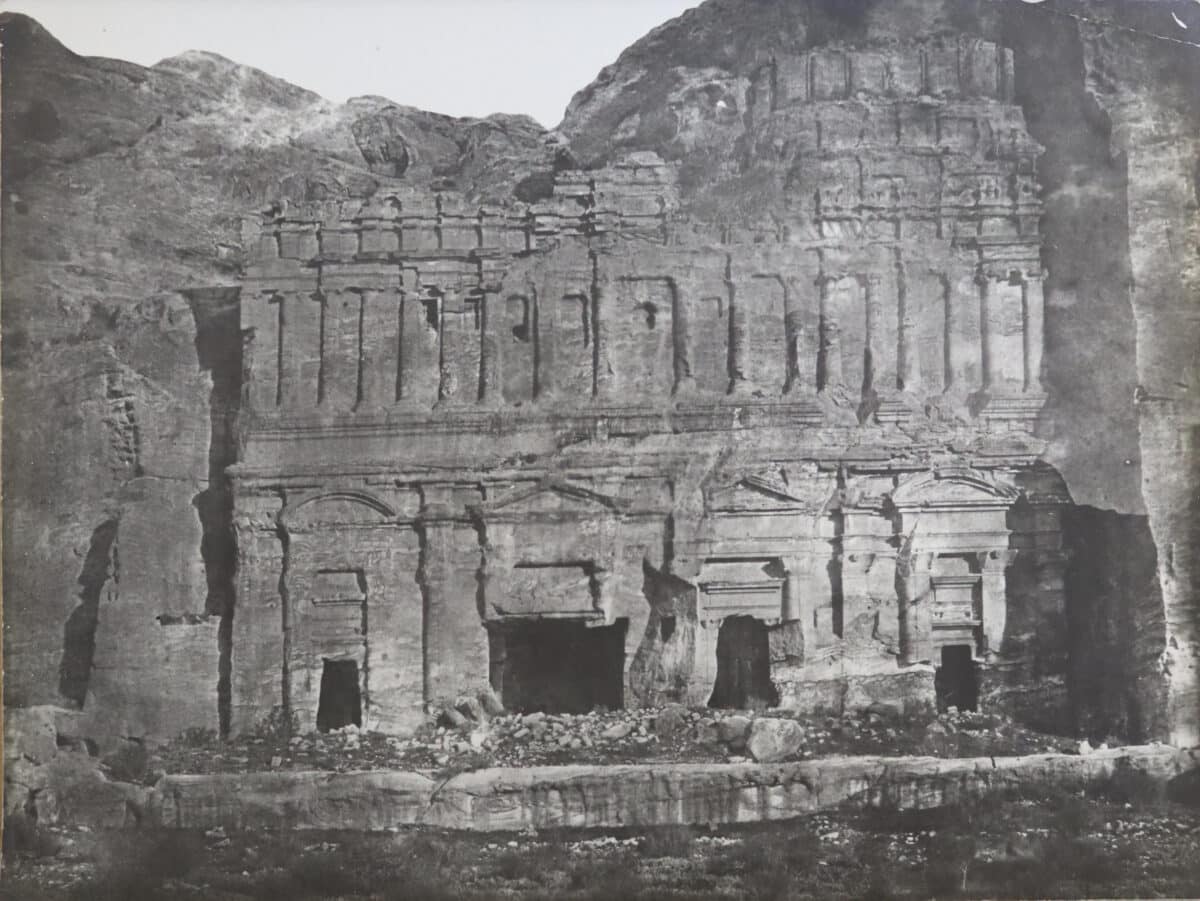

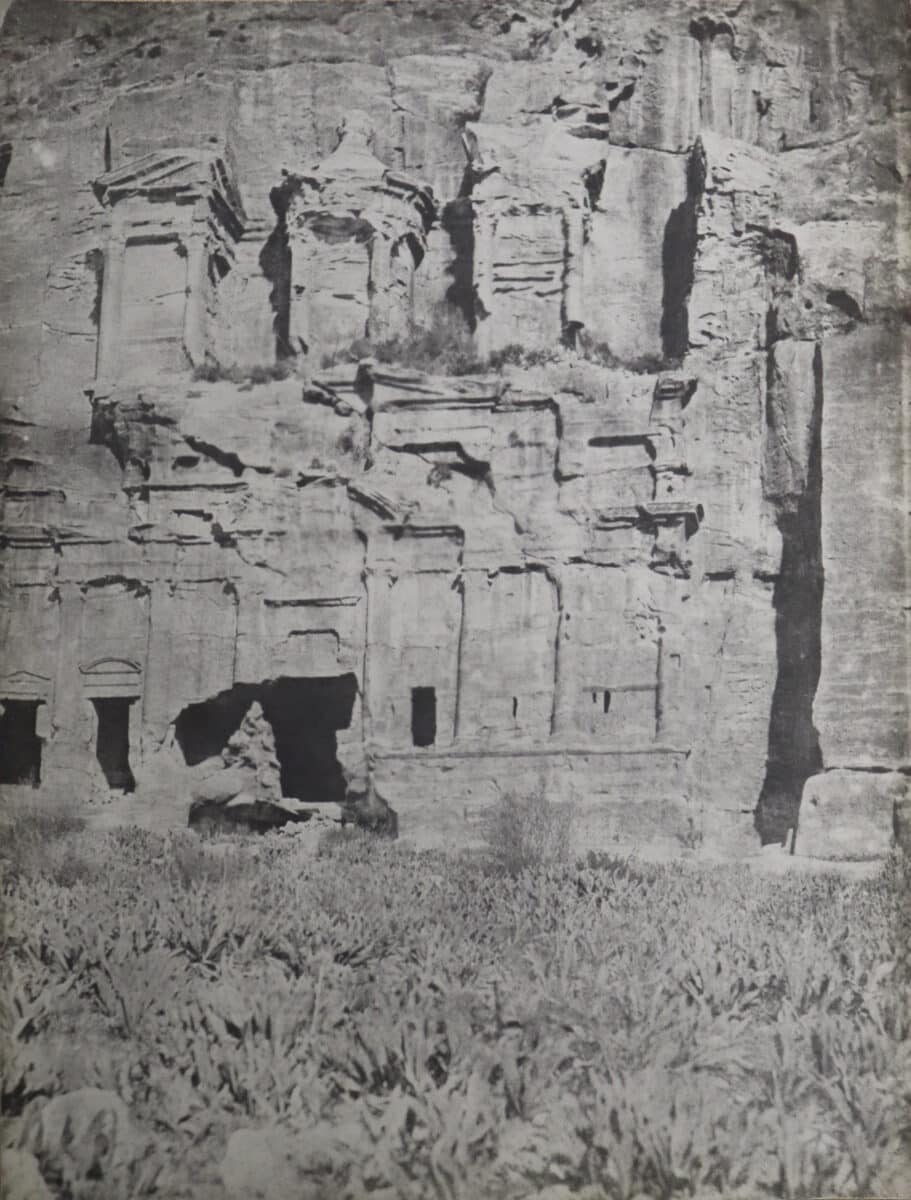

John Shaw Smith had been the first traveller to visit Petra with a camera, six years before Lear. These first monochrome photographs made stark the impossibility of describing the coloured striations of the local sandstone. [2] It was the interior of the Tomb of the Urn (Fig.1), high on the north side of the valley and opposite the Theatre, that became for everyone the focus of this frustration.

‘There were no paintings or decorations of any kind within the chamber; but the rock out of which it was hewn, like the whole stony rampart that encircled the city, was of a peculiarity and beauty that I never saw elsewhere, being a dark ground, with veins of white, blue, red, purple, and sometimes scarlet and light orange, running through it in rainbow streaks; and within the chambers, where there had been no exposure to the action of the elements, the freshness and beauty of the colours in which these waving lines were drawn gave an effect hardly inferior to that of the paintings in the tombs of the kings at Thebes. [3]

… many of them, however, are adorned with such a profusion of the most lovely and brilliant colours as, I believe, it is quite impossible to describe. Red, purple, yellow, azure or sky-blue, black, and white, are seen in the same mass distinctly in successive layers, or blended so as to form every shade and hue of which they are capable -as brilliant and as soft as they ever appear in flowers or in the plumage of birds or in the sky when illuminated by the most glorious sunset. The red perpetually shades into pale or deep rose or flesh colour. The purple is sometimes very dark, and again approaches the hue of the lilac or violet.

The white which is often as pure as snow, is occasionally just dashed with blue or red. The blue is usually the pale azure of the clear sky or of the ocean, but sometimes has the deep and peculiar shade of the clouds in summer when agitated by a tempest. Yellow is an epithet often applied to sand and sandstone. The yellow of the rocks of Petra is as bright as that of saffron. It is easier to imagine than describe the effect of tall, graceful columns, exhibiting these exquisite colours in their succession of regular horizontal strata. They are displayed to still greater advantage in the walls and ceilings of some of the excavations where there is a slight dip in the strata. This gives, in the perpendicular sides of the excavation, greater breadth and freedom to the exhibition of colours, while in the ceiling, the plane of which makes a very acute angle with that of the strata, the effect is indescribably beautiful. The colours here have full play and expansion, and they exhibit all the freedom of outline and harmonious blending of tints observable in a sunset scene. The ceiling of a large excavation just at the entrance of Wady Syke, and nearly opposite to the amphitheatre, affords an example of the magnificent effect which I so vainly attempt to describe. In the northern half of the ceiling a brilliant deep red is the predominant hue, intermingled, however, with deep blue, azure, white, and purple.

… The interior, which is without any ornament but the exquisite colouring I have already tried to describe, is in a better state of preservation than any other excavation which I examined, still bearing the marks of the chisel in every part. It is twenty-one paces square, having six recesses of various size in the wall. It was probably a tomb.

I have been not a little mortified at ascertaining the impossibility of obtaining and transporting specimens of the beautiful Petra stone. It happens that the strata which are of the softest and most elegant colours are precisely those which possess the most frail and delicate texture. The yellow, rose-colour, azure, and white strata are disintegrated by the falling rain, and it is extremely difficult to disengage them from the rock, either separately or in a mass of various colours, without resolving them into their constituent particles; and I deem it quite impracticable to transport them on camels without some method of preserving them not now at my command.’ [4]

But it is Lear’s Suliot cook, Giorgio Cocali, to whom, as ever, we must give what is (almost) the last word: ‘“Oh master,” said Giorgio (who is prone to culinary similes), “we have come into a world where everything is made of chocolate, ham, curry powder, and salmon.”’

Asked on 27 February 2023 to ‘describe the striated sandstone at Petra’, ChatGPT gave a description of a beauty markedly less edible:

‘The striated sandstone at Petra, Jordan is a stunning sight. The rocks have been naturally worn away by the wind, creating layers of ridges and grooves in the otherwise smooth sandstone. The striations range from light brown and beige to shades of deep red, orange, yellow, and purple—creating lines of breathtakingly beautiful visual texture. The different hues, shapes, and sizes all make the sandstone seem almost magical, as if it is a scene from a movie. The striated sandstone is an amazing site to see and offers a unique experience for visitors to Petra.’

Notes

- Edward Lear, ‘A Leaf from the Journal of a Landscape Painter’, Macmillan’s Magazine LXXV (April 1897), pp.410 – 430.

- ‘… and the sandstone of colors the most astonishing, scarlet shaded down to the most delicate pink, purple, white, yellow, orange, all most brilliant’. Mary Shaw Smith and John Shaw Smith, transcript from John Shaw Smith’s Travel Diary, vol.3, Monday, March 22nd 1852, p.112. Coll-20, Centre for Research Collections, University of Edinburgh.

- John Lloyd Stephens, Incidents in Egypt, Arabia Petraea and The Holy Land, vol. 2 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1837), pp.59 – 60.

- Stephen Olin, Travels in Egypt, Arabia Petraea and the Holy Land, vol. 1 (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1843), pp.22 – 24.

DMJournal–Architecture and Representation

No. 1: The Geological Imagination

ISSN 2753-5010 (Online)

ISBN 978-1-9161522-3-6

About the author

Niall Hobhouse is Director of Drawing Matter and chairs the Drawing Matter Trust.