Masterplanning the University of London

Legend has it that Charles Holden promised the University of London a building that would last five hundred years. While there is no hard evidence for Holden’s claim, his Senate House (1932–37) looks as permanent as anything built in modern Britain. A 19-storey tower faced with granite and Portland stone, the structure was London’s tallest secular building when it opened; and after Holden added his ‘garden cloister,’ flanked with a series of college buildings (including SOAS, Birkbeck and my own Warburg Institute), it has become impossible to imagine Bloomsbury with anything else at its centre.

Yet neither the presence of the University of London nor Holden’s approach to its campus were a given. As we discovered in preparing an exhibition called Charles Holden’s Master Plan, Holden was not the first architect tasked with planning the University’s new home, and the estate as delivered was not what he first designed.

The story starts in South Kensington. By the end of the 19th century, the University had established its headquarters in the neighbourhood known as ‘Albertopolis’—in recognition of Prince Albert’s vision for bringing together buildings devoted to collections, education and policy in the wake of the Great Exhibition of 1851. The land on either side of Exhibition Road housed national museums for art and science and royal colleges for everything from music to mining. On the site of what is now Imperial College a massive building called the Imperial Institute contained the examination halls and administrative offices for the University of London—first chartered in 1836, with federal members spread around the capital.[1]

At the turn of the 20th century, powerful figures in both academic and political administration lobbied for a new and central home that would serve the University’s ambitions. In 1911, Lord Haldane’s Royal Commission on University Education in London concluded that:

‘The University should have for its headquarters permanent buildings appropriate in design to its dignity and importance, adequate in extent and specially constructed for its purpose, situated conveniently for the work it has to do, bearing its name and under its own control.'[2]

The places proposed included Somerset House, the Foundling Hospital, Gray’s Inn Gardens, Pentonville Hill, the Crystal Palace, the Botanical Gardens in Regent’s Park and the South Bank site now occupied by the National Theatre. But Haldane himself preferred Bloomsbury.

The idea of making Bloomsbury the city’s ‘Knowledge Quarter’ goes back to the founding of the British Museum/British Library in 1753. By 1827, University College London (UCL) had started building its classical quad around the old Carmarthen Square, followed by a cluster of complementary institutions that would rival South Kensington. Most of the neighbourhood was still owned by the Dukes of Bedford; but when they made more than 11 acres of land immediately to the north of the British Museum available for redevelopment around 1911, the University saw it as an opportunity to move its base of operations from Albertopolis to the Bedford Estate.

The first scheme was drawn up by the Duke’s own Surveyor, Charles Fitzroy Doll (1850–1929). Best known for designing the dining room on the Titanic, he left his mark on Bloomsbury with an imposing pair of ornate hotels on the eastern edge of Russell Square (the Russell [1898] and the Imperial [1905]). It was Doll’s office that produced the earliest surviving drawing for the University’s proposed campus in 1912—the year he served as mayor of Holborn. Attributed to C. Harrold Norton, and recently acquired for the University’s archive, the plan is decidedly old-fashioned, its style entirely in keeping with the classical porticos found on both the British Museum to the south and UCL’s Main Building to the north.

The site was not sold at this time and Doll’s scheme was all but forgotten. At the end of World War I, the Board of Education revived the idea of bringing the University to Bloomsbury and offered to buy the entire site. In March 1920, the land was purchased from the Duke of Bedford for £425,000 with an option to return it for the same price within six years. There turned out to be too many strings attached to the Government’s offer (which would have required King’s College to surrender its base on the Strand), and in March 1926 the unchanged estate was sold back to the Duke.

The University would have remained ‘beguiled [in] the wilds of South Kensington’ (as Dr T. L. Mears put it in his testimony to the 1911 Haldane Commission) had it not been for the election of William Beveridge as Vice-Chancellor in June 1926.[3] Mostly remembered for the report that created the modern welfare state and for his long leadership of the London School of Economics, it was Beveridge who not only convinced his reluctant colleagues to make the move (presenting an irrefutable paper in which he ‘plotted the position of the eighteen larger schools of the University…in relation to South Kensington and to the Bloomsbury site, and compared the distance, time of travel, and cost of travel, to each of these alternative centres’) but also raised the funds needed to buy the land (persuading the Rockefeller Foundation to contribute £400,000 toward the final purchase price of £525,000 and the Government to cover the rest).[4]

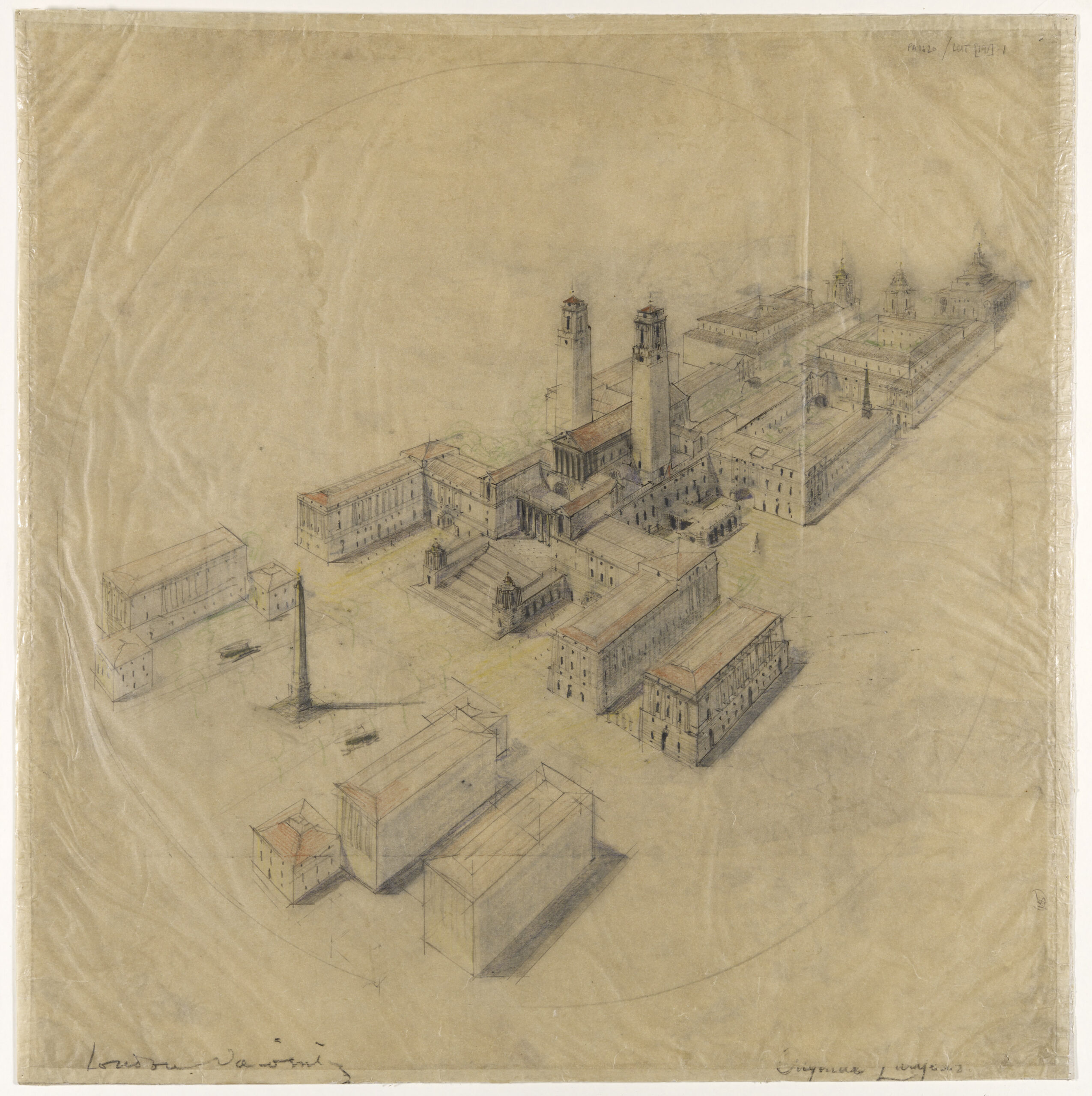

Having secured the site, the University might have engaged its own architect, William J. Walford; and both A. E. Richardson and H. V. Lanchester eagerly came forward with their own schemes. Perhaps under pressure from the Government, Beveridge and his colleagues seem to have turned (or rather re-turned) to none other than Edwin Lutyens (1869–1944), who had produced some sketches for the new campus as early as 1922. Only a few months after the land was acquired in the summer of 1927, Lutyens revisited the project and drew up a fantastically ambitious plan.

Surprisingly little-known, the scheme is preserved in six large drawings now housed in the RIBA Archive.[5] It offers a sort of architectural fantasia, with components drawn not only from many times and places but also recycling his own earlier work in England and India. There are echoes of the Roman complex at Palestrina, monumental ‘Steps of Honour’ leading to a Greek revival façade, twin bell-towers and even an obelisk marking the boundary with the British Museum. In the apt words of J. Mordaunt Crook, ‘Lutyens’ grandiloquent arrangement of porticoes, plinths and colonnades…conjures up, even now, images of New Delhi in Bloomsbury’—or rather Lucknow, since the central building was repurposed from an unbuilt design for its new university in 1920–21.[6]

History does not record what the University made of Lutyens’ drawings, but Beveridge soon announced a new architectural competition in a Graduation Day speech that he summarised for his hard-of-hearing mother:

‘Give us the means to take [the University] and hand it to some inspired artist in steel and stone and marble—not too much marble—and let him embody it in a group of buildings, of surpassing beauty, which later generations will set beside Westminster. Lovers of London, lovers of beauty, lovers of learning…this is a work for them all to share.'[7]

Along with the University’s Principal, Edwin Deller, Beveridge himself set the brief for the project and served on the selection committee that narrowed the list of candidates to four—each of whom was interviewed over dinner at the Athenaeum. They chose the only architect (as Beveridge later recalled) ‘who came with a first sketch in his hands.’

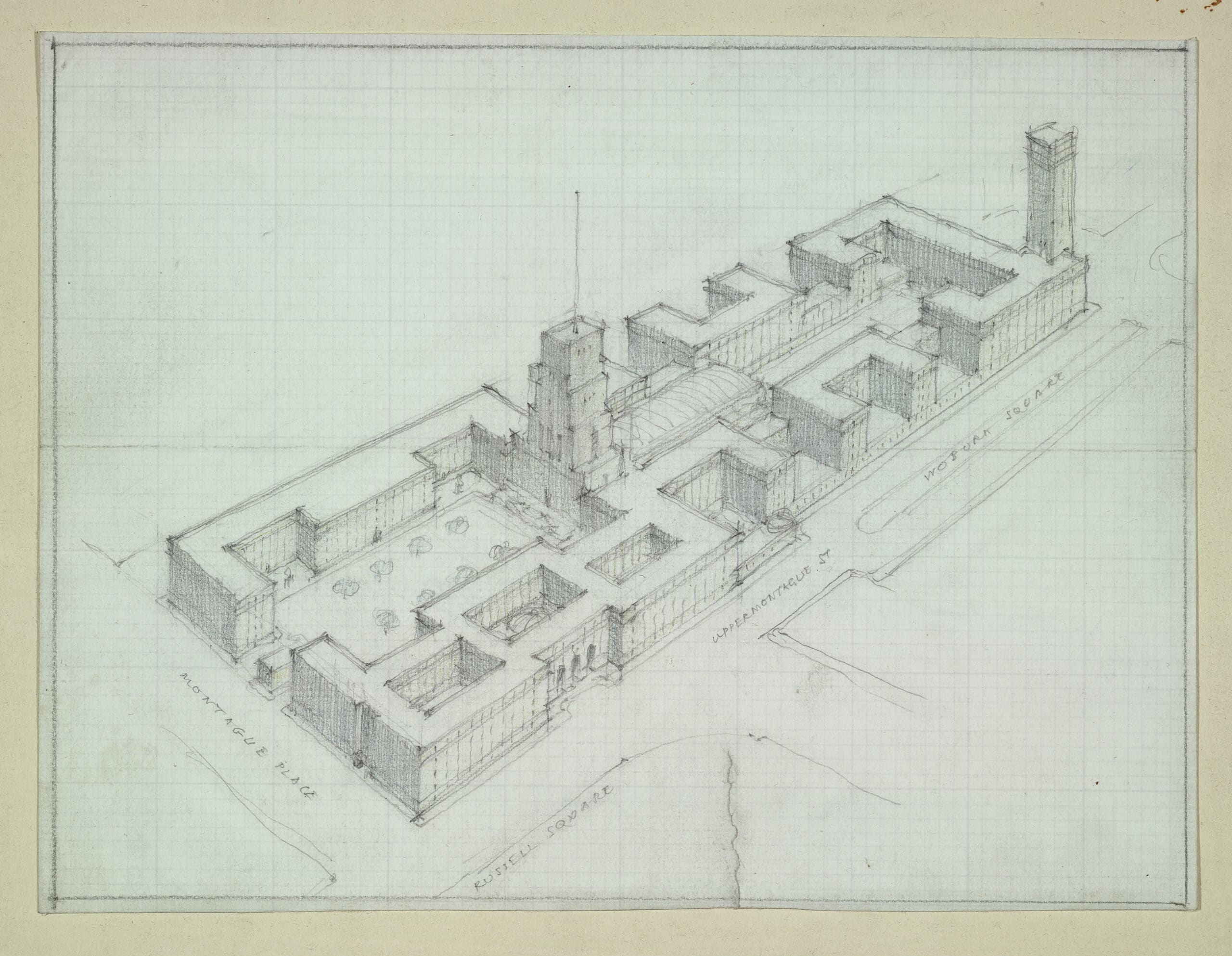

That architect was Charles Holden (1875–1960) and the sketch may well have been one of the many for the scheme preserved among the papers of Adams, Holden and Pearson in the RIBA Archive.[8] Perhaps the earliest dates from c.1931 (Fig. 3) and it clearly pushes the stripped classicism for which he had become known to the point of modernist abstraction. It is hard to believe that it was drawn less than twenty years after Norton’s scheme for the Duke of Bedford. While it seems to come from the distant future, both Holden’s selection and his style owed much to a more immediate and local precedent—his extensive work on the London Underground. In the 1920s and 30s, Holden built or redesigned no fewer than 48 Tube stations as well as the network’s monumental headquarters at 55 Broadway. It was apparently his tour of that building—which looks in retrospect like Senate House’s smaller sister—that persuaded Beveridge and Deller to hire Holden for a project that would take more than 25 years.

In 1932, Holden presented the University with a formal prospectus: using the London Underground’s official font and one of its regular artists for the patterned cover, Holden’s booklet carried the modest title New Buildings on the Bloomsbury Site.

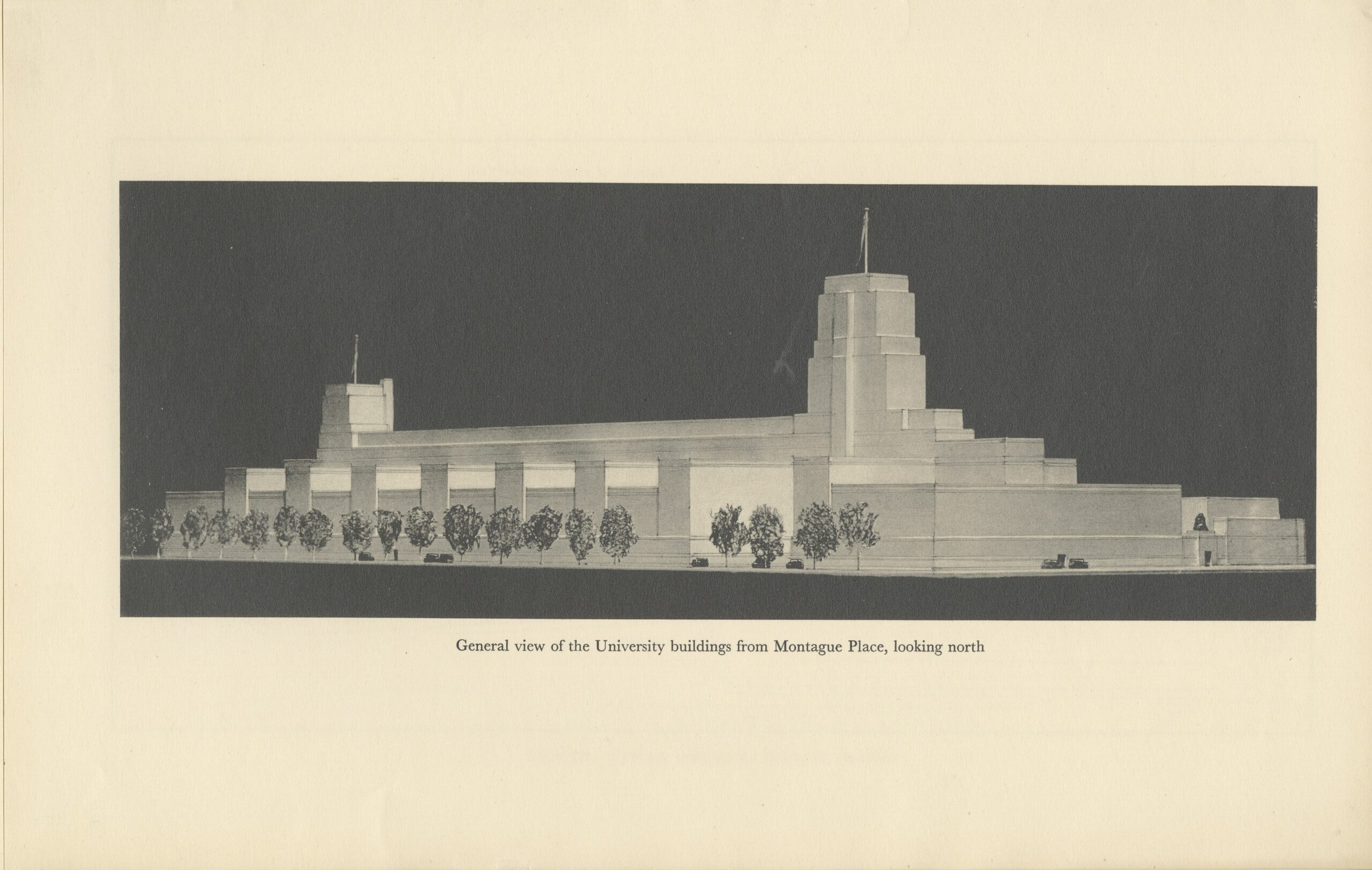

There was nothing modest about the scheme it described: a series of striking photos show a model for a single ‘spinal’ structure—stretching a quarter of a mile and containing 17 modular courtyards. Within a few years a so-called ‘balanced’ scheme emerged, with free-standing but closely connected buildings around a landscaped garden. The official model, recently restored by the University, includes several structures that were never built, including the fourth wing of Senate House, an adjacent auditorium for 3,000 people opening onto Russell Square and a linking loggia (with glass-fronted floors above) creating a clear entrance to the campus from the north.

Perhaps the most poignant signs of compromise in Holden’s unfinished vision are the empty plinths installed above the entrance on both sides of Senate House. The architect intended visitors to pass under sculptures by Jacob Epstein or Eric Gill (as they did at 55 Broadway), but the University did not agree with Holden’s controversial artists. It did, however, commission a large painted map from Gill’s younger brother MacDonald for the back wall of the Chancellor’s Hall. The artist best-known for his depiction of the ‘Wonderground’ (sometimes referred to as ‘the map that saved the Underground’) here shows the capital’s education rather than transportation infrastructure. Dated 1939 and featuring astonishingly detailed portraits of all of the University’s key buildings, Gill kept working on the map throughout the war; but it was hurriedly installed in 1946 for the granting of an honorary degree to Princess Elizabeth, and was never finished. It feels almost emblematic that among the blanks that remain is the oversized cartouche above Holden’s magnum opus that should have identified the very building for which the map was painted.[9]

With the completion of the Warburg Renaissance project now on the horizon, and consultations underway for both ends of the Bloomsbury campus (not to mention a massive capital project next door at the British Museum), we are back in masterplanning mode. While compromises seem more inevitable than ever, let’s hope that the projects will be informed, if not inspired, by the ambitious visions of those who first shaped the neighbourhood within which the University continues to sit.

Notes

- Negley Harte, The University of London: 1836–1986 (London: The Athlone Press, 1986), 164–166.

- J. Mordaunt Crook, ‘The Architectural Image,’ in F. M. L. Thompson (ed.), The University of London and the World of Learning, 1836-1986 (London: The Hambledon Press, 1990), 1–33 (15).

- Crook, ‘The Architectural Image,’ 14.

- William Beveridge, Power and Influence (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1953), 196.

- Catalogued as item 191 in Margaret Richardson’s 1973 Catalogue of the Drawings Collection of the Royal Institute of British Architects, the drawings were tentatively dated c.1914; but when Richardson returned to them for her later monograph on Lutyens (Sketches by Edwin Lutyens: RIBA Drawings Monographs No.1 [1994]), she adjusted the date to 1927.

- Crook, ‘The Architectural Image,’ 18; Richardson, Sketches by Edwin Lutyens, 93.

- Beveridge, Power and Influence, 205.

- The best account of Holden’s career, culminating in his work for the University, is Eitan Karol’s Charles Holden, Architect (Donington: Shaun Tyas, 2007).

- Caroline Walker, MacDonald Gill: Charting a Life (London: Unicorn, 2020), 306.

Professor Bill Sherman is Director of the Warburg Institute, University of London.