A Chevrolet Truck

It was the architect Philip Johnson who first compared cars to statuary. In the ‘Eight Automobiles’ show he curated at the Museum of Modern Art in 1951, he coined the expression ‘rolling sculpture’. Johnson was good at coinages: two decades before he had given us ‘the International Style’ to describe interwar European Modernism.

The similarity of car design to architecture has often been noted. Nikolaus Pevsner said the one was ‘a mobile controlled environment’ and the other was a ‘static controlled environment’. As simple as that. And the epicene Parisian savant, Roland Barthes, was sent into raptures by the sight of the new Citroën at the 1955 Paris Salon de l’Automobile. He said the car was ‘l’equivalent assez exact des grandes cathedrales’, and then nicely glossed the craft of car design itself as ‘le meilleur messager de la surnature’.

True, cars can be understood, like buildings, in terms of plan, front elevation, side elevation and section. Like buildings, they have formal and spatial complexities that can only be understood in-the-round. And they also carry a heavy weight of symbolism, something enjoyed and exploited by both Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright.

Corb, during his International Style phase, always posed handsome cars in photographs of his white villas. He even made a counter-factual claim to be the intellectual father of the Citroën 2CV. Wright, for his part, invented the carport and essayed what became the Guggenheim Museum in a design for a Park Avenue car showroom.

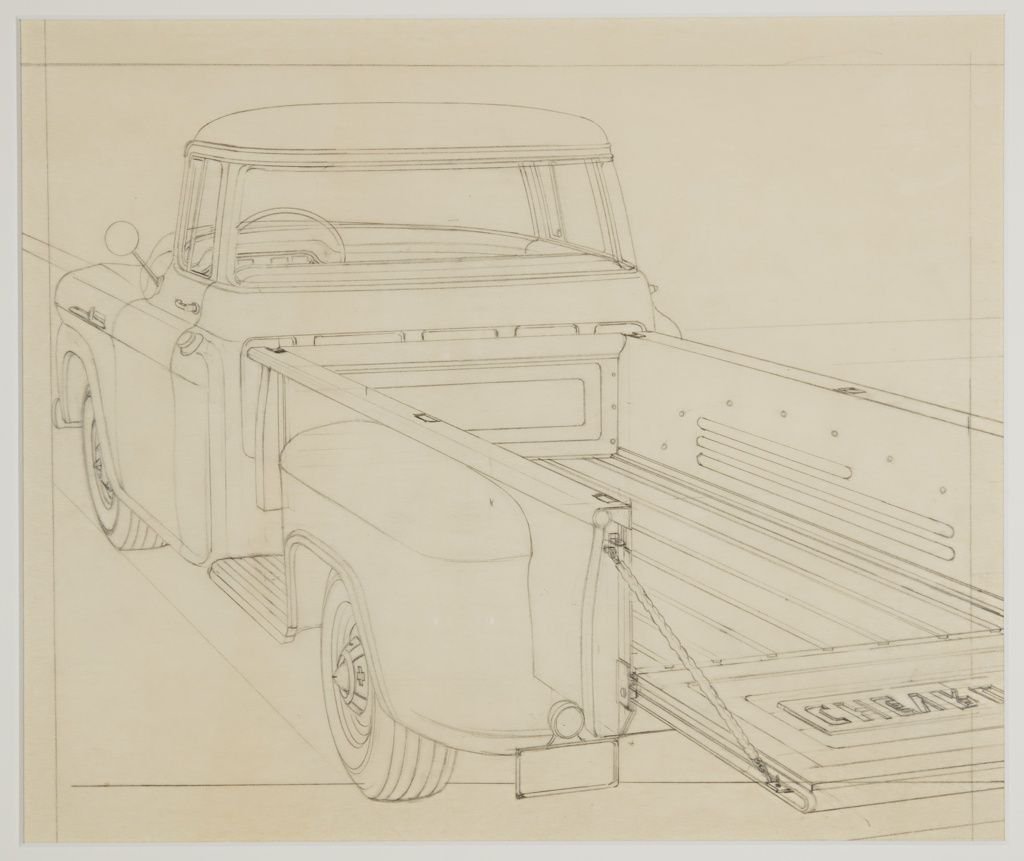

This fine drawing of a Chevrolet pick-up truck was acquired by the Cooper-Hewitt, the Smithsonian’s New York design museum, in 2017. The draughtsman was John Chilka. It is a curiosity that many of the pioneers of the car industry, Ferdinand Porsche included, came from a not-yet-industrialised Central Europe. Chilka was born in 1912 in Knezdub, a village in Moravia, but by 1934 was in Detroit working for General Motors.

Who is to say how the glorious romance of American industrial culture affected him? But what’s certain is that he arrived in Detroit when Harley Earl’s Art and Color Section of General Motors was establishing the studio techniques which are still in use in car design today. These included full-size clay modelling, 1:1 tape ‘drawings’ of vehicle profiles and huge renderings in gouache or airbrush used in presentations to management.

This drawing was a ‘final tissue’ made in graphite on lightweight paper, normally a part of the preparatory process for the later renderings. It is very assured in execution and bold in composition: the fully realised rear three-quarters view is unusual in drawings of this type. Clearly, Chilka enjoyed the Chevy’s spatial complexity and his drawing evokes the impressive substance of the truck while making in and of itself a beautiful graphic pattern.

But there is an anomaly in the Cooper-Hewitt’s dating of the drawing. Chilka left General Motors in 1939. The museum dates the drawing 1934–39, his period of employment in Detroit. But the truck in the drawing is clearly a 1955 model, not a mid-30s design.

In the early 1980s, when I was researching my book on Harley Earl in GM’s Tech Center in Warren, Michigan, the archivists were unable to show me any drawings of the 1950s cars that interested me. They explained it was not the corporation’s policy systematically to bother collecting such things. That may even be true.

So it seems that Chilka’s lovely drawing of a Chevrolet truck is not an archaeological fragment from the design process of the thirties, but a retrospective, sentimental hommage to Mid-Century Modern: the period Tom Wolfe called America’s ‘Bourbon Louis romp’. And it proves, if proof were needed, that drawings of cars often create as many delicious scholarly questions as drawings of buildings do.

– Michael Webb