After the Revolution: Dugourc in Spain

After Jean Démosthène Dugourc’s forays into revolutionary paperwork, his return to silk and his migration to Spain to work for the Bourbons in 1800 places pressure on understanding his revolutionary activities, and whether he indeed had but briefly dabbled in the politics of the period before ultimately wishing, in his words, ‘to only serve Bourbons’. [1] Dugourc had been working for the Spanish court from Paris as early as 1786; he decided to move permanently to Madrid following the death of his business partner, the entrepreneur François-Louis Godon. [2] His designs for silks and architectural follies in Spain pushed the more restrained decorations he had created during the ancien régime to greater extremes, incorporating Chinese and Egyptian motifs alongside his trademark arabesque patterns, as well as more elements of fantasy and colours; in Spain, he sought to outdo the most extravagant designs of the ancien régime. For example, it is hard to trace any kind of ostensibly revolutionary sensibility in the colourful arabesque silks he designed in Spain for Charles IV, which drew once more upon the decorative motifs of the Loggia. [3]

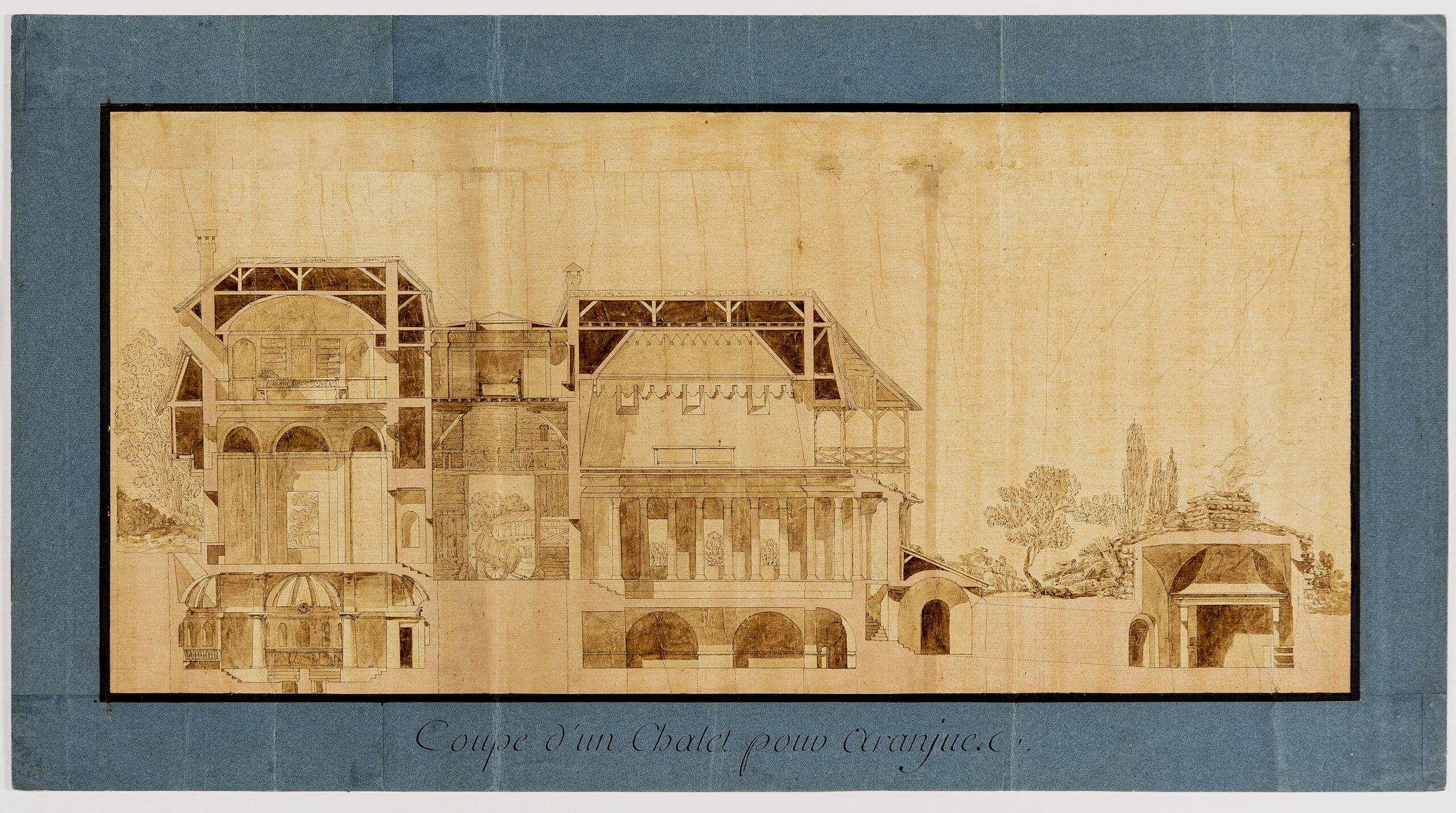

Officially named a royal architect in charge of the palace at La Moncloa in 1802, Dugourc provided architectural designs to the Spanish king and his court, including the influential minister Manuel Godoy, even though he had not been formally trained as an architect. [4] Alongside creating extravagant arabesque decorations for the king’s spaces, he sought through his architectural projects to resuscitate in rural Spain all of the grand designs that had once populated ancien régime Paris, as if the Revolution itself had never transpired. Three years after Dugourc arrived in Spain, François-Joseph Bélanger, in his typically sardonic way, wrote to the furniture maker Georges Jacob that ‘your former master M. Dugourc, is resuscitated: he is the first architect to the king of Spain and of the prince of the Peace’. [5] One particularly ambitious proposal for a chalet at Aranjuez evokes many of the elements that Bélanger had used at Bagatelle, including the tent room, as well as the royal hamlet made for Marie-Antoinette at Versailles. Dugourc’s rustic pavilion resembles a wooden shack, complete with log piles and a thatched roof, perhaps in keeping with Charles IV’s love of rural life. [6] It is unlikely that such a half-conceived structure was ever built. [7] Nonetheless, in a similar manner to the dovecote that Pierre-Adrien Pâris had reconfigured into a house for himself at Colmoulins, Dugourc’s fancy shack performs architectural subterfuge, betraying an anxiety about ornamental ostentation in hiding columns, grotto-like spaces, and an alcove bedroom behind a truly dilapidated exterior.

The loose ends of one’s life never quite work out as neatly as the tightly woven and repeating patterns of the silk panels that Dugourc was tasked with designing in Spain, so vibrant, so symmetrical, and so perfectly ordered. The Empire eventually caught up with the French designer, and, eight years after he arrived in Madrid from Paris, Dugourc was followed by his compatriot Joseph Bonaparte, who deposed King Ferdinand VII in a matter of months and placed himself on the throne in 1808, backed by his brother Napoleon. The French emperor is the subject of an unusual drawing by Dugourc; it shows him in alternating profiles, the youthful and idealised portrait haunted by the ghostly presence of an older and perhaps more accurate version of the Napoleon of that moment, his saggy profile registering the effects of all the military campaigns that would not touch the perfectly repeating ornamental pattern figured below in a vertical foliage motif, a little bit of free beauty next to a face subject to the vicissitudes of time.

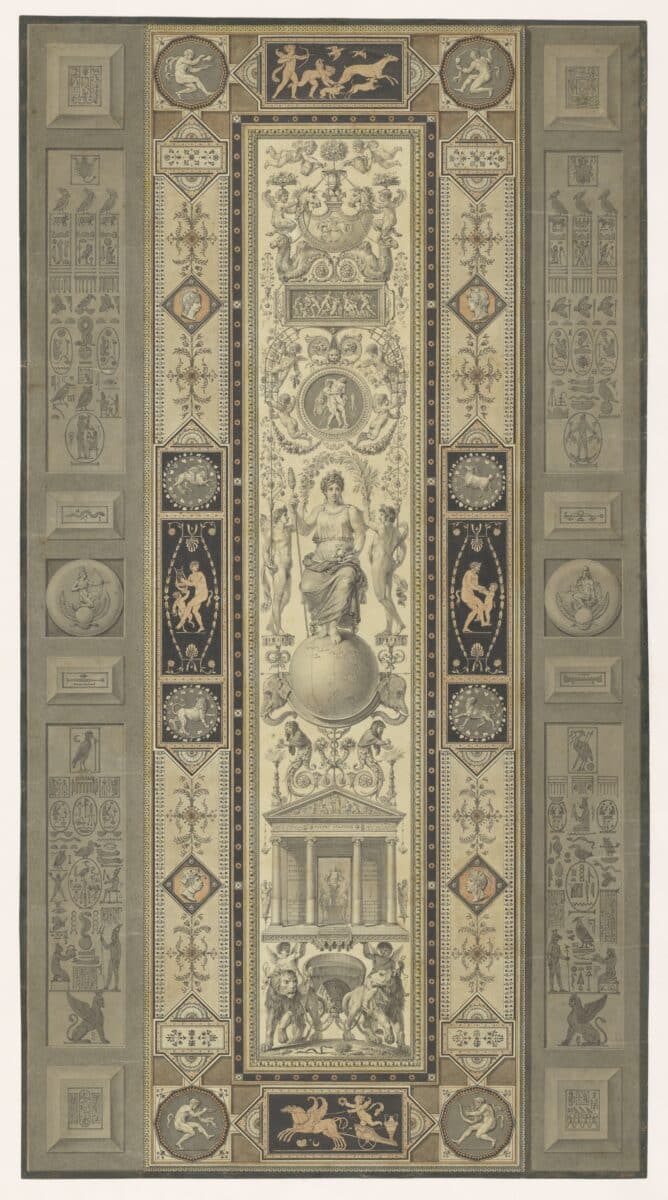

Paper was the medium upon which Dugourc’s past had depended and the means through which he hoped to secure a lucrative future. A large presentation drawing from 1808 attests to the ways he sought to once more use his skills as a draftsman to save himself from exile and to adapt once again to the shifting political allegiances brought about in the wake of the Revolution. Among the largest of Dugourc’s surviving drawings, the image’s exact function is unclear, although it is accompanied by a small slip of paper that reads, ‘this sheet was begun in Paris in 1787 and completed in Madrid in 1808 by J. Démost. Dugourg architecte du Roi Joseph Napoléon’. A sort of memory palace, the composition combines many of the motifs associated with the goût étrusque style that the designer had pioneered and helped to propagate during his early successes with Bélanger in a range of materials, from silk panels and furnishings to delicate gilt-bronze mounts for precious hardstone objects. The central vertical section in the drawing shows a seated female figure who plants her feet upon a globe that shows the African continent; she sits between two male attendants, one with butterfly wings and the other wearing a crown of wheat. [8] Several of the grotesque motifs recall the plates from Arabesques, which drew from the Vatican Loggia, while the exotic and fantastical beasts interspersed throughout the design include camels, elephants, unicorns, and squirrels – animals that would reappear in Dugourc’s illustrations for Les animaux savants, published in 1816. The panel is set into a frame decorated with black and terracotta cartouches evocative of Greek vase paintings, separated from two outer bands of Egyptian-style decoration in a gray wash. At the bottom half of the composition, a Roman tetrastyle temple contains a statue of Cybele. The inscription on the outer walls of the temple reads, ‘j. démost. dugourc architect inv. del’. The cornice of the inner structure contains the dates of the drawing’s commencement in Paris in the year of 1787 and of its completion in Madrid in 1808.

While the drawing’s format recalls the long panels of woven silk that Dugourc designed for Camille Pernon on behalf of the Spanish court, it does not correspond to a specific commission or known royal project. As evidence of this, we need only glimpse at the structure located in the centre, emblazoned with the artist’s name and profession within the frieze of the temple dedicated to the Great Mother. Even if indeed, following the hypothesis put forward by R. J. A. te Rijdt, the drawing served as ‘a sample of archeological motifs allowing the artist to demonstrate all of his savoir-faire’, it does not tell us why it took Dugourc nearly twenty years to finish this drawing, nor the practical matter of why he chose to make an ‘advertising card’ in such a large format. [9] On another level, it raises the question of why a draftsman who had been employed by countless other artisans and architects, chief among them Bélanger, decided to chisel his name as an architect within the edifice of his design.

What kinds of representational anxieties were at work in 1808 in Madrid for one of the most prolific designers of ancien régime Paris, who would be remembered a century later for his works on paper and as the radical printmaker of republican playing cards? [10] The strangest aspect of the drawing is the way in which Dugourc drew himself into a tomb, the carefree and loose footwork of earlier arabesque patterns turned into coffers and containers and caskets, set one into the other in an interlocking and inescapable system as conservative and funereal as the Egyptian motifs found in the outermost edges of the drawing. Gone were the ambiguous fantasies of the past, the fugitive designs with openings and closings in between the threads that had allowed for the traffic between politics and pleasure. Instead, the design was so tightly woven that no gaps could be left behind.

Stylistically, the heavily controlled composition evokes the kind of images Dugourc would make for the Bourbons during the Restoration, after he returned to Paris from Madrid in 1813, drawing the funeral procession for Louis XVI and taking charge of designing the lavish silk brocades for the throne of the Palais des Tuileries in 1819 but never quite managing to find a solid position under the Restoration. [11] The conservative, somber quality of the drawing is picked up in the strange sepia tones and muted shades, which create the effects of a reproductive print more than an original drawing and look forward to the cinematic strategies of using muted tones in film in order to signal a flashback to the past. Instead of signing his name on the outer margins, outside the mimetic framework of the drawing, as was typical of eighteenth-century drawing conventions, he chose to sign his name inside, in the sanctum sanctorum of the centre of the composition. Significant indeed is the temple at the heart of the drawing, where Dugourc has chosen to leave his name chiseled on the surface of a sanctuary dedicated to the Great Mother, whose death called him back from Rome and cut him off from the true knowledge of antiquity, but whose absence shaped the arabesque fantasies that arose from the designer’s sleight of hand.

Extracted, with permission, from Luxury After the Terror by Iris Moon, published by Penn State University Press, available here. Follow the link below to read about Dugourc’s design of playing cards, also extracted from Luxury After the Terror.

Notes

- Jean Démosthène Dugourc, ‘Demande de gratification’, p.103.

- Sancho, ‘Arts at the Court of Charles IV’, p.27.

- For examples of the same fabric panel in other collections, see Anna Jolly, Fürstliche Interieurs, pp.178–82.

- Charles IV appointed Dugourc on August 7, 1802. See Sancho, ‘Arts at the Court of Charles IV’, p.27; note 40.

- Christian Baulez, ‘Imaginations de Dugourc’, p.30.

- On Dugourc’s failures as an architect in Spain, see ibid., p.30.

- Jordán de Urríes y de la Colina, Real Casa del Labrador, p.61.

- R. J. A. te Rijdt, De Watteau à Ingres, p.243. See also Reinier Baarsen, Paris, 1650–1900, p.445.

- Rijdt, De Watteau à Ingres, p.243.

- See Jules Renouvier, Histoire de l’art pendant la Révolution, pp.374–81.

- On the decorative arts during the Restoration, see Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, Âge d’or des arts décoratifs.