Architecture in Archives: The Collection of the Akademie der Künste (2016) – Review

Archives, particularly architecture archives, are having a moment. Writers of postcolonial histories increasingly wrangle with their neatly preserved and selected records. Predominantly, documentary evidence under archival care formed the basis for official histories – histories that are by now largely exhausted, if not downright discredited. As traditional sites of hegemonic authority, archives have increasingly come under scrutiny and are challenged to provide different kinds of evidence and to enable the construction of alternative narratives. Having long had their contents tailored to historical agendas most archives are, by and large, woefully imbalanced in terms of parity and diversity. Although ill-equipped to react quickly and meet the demands of changing scholarship, archives remain a favoured site for gathering knowledge by being read ‘against the grain’. [1]

Prior to current critical interest in the content and curation of archives, the genre of archive publications has been, by convention, neither questioning nor subversive. Rather than providing the background information upon which historical discourse rests, its primary aim has been to shine a light on the archival holdings in and of themselves – to offer a privileged view over the coulisses of historical research. Before, and in parallel to online catalogues, such paper publications have taken many forms, from fold-out flyers and giveaway postcard sets to brochures, books, and – as demonstrated by the current publication – Very Large Books. Whatever the format, they aim to provide a sweeping overview, an imperious gaze that falls on a collection’s most valued highlights.

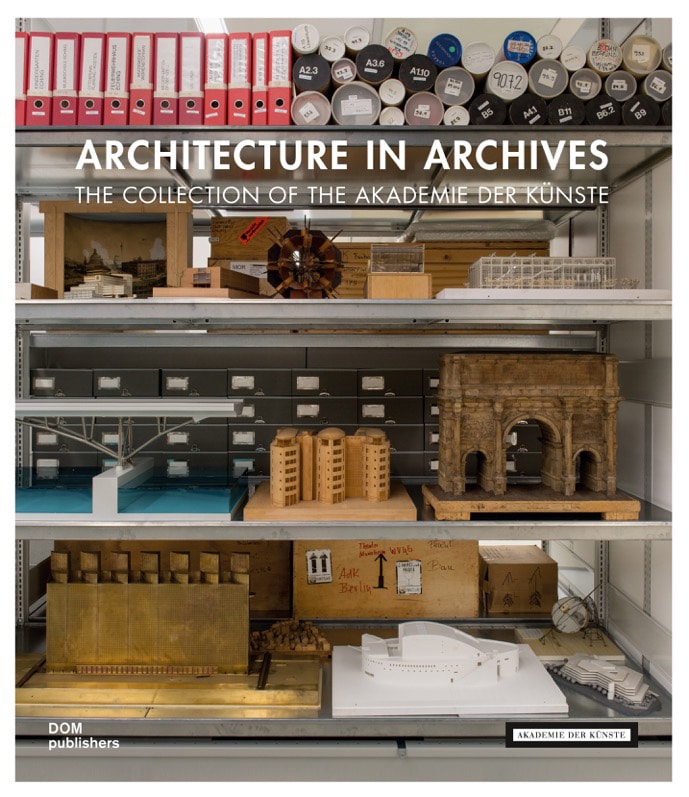

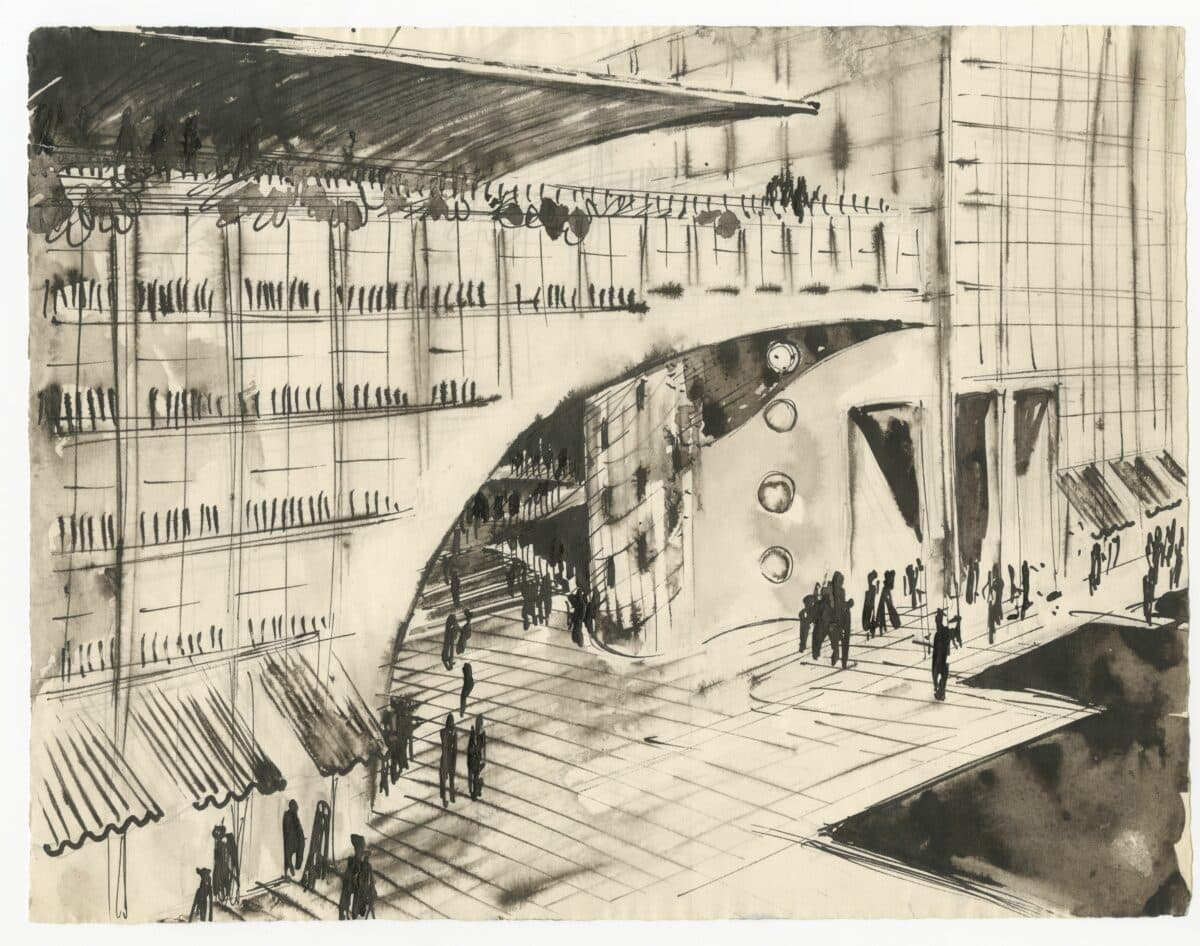

As the official publication of the prestigious Architectural Archives of the Akademie der Künste in Berlin, Architecture in Archives illustrates the case in point. The book reflects the bulk and dignity of an establishment institution with – according to their online page – 350,000 plans and drawings, approx. 100,000 photos, a kilometre of written material, and 450 models. It consists mostly of a catalogue of selected archival items from the collection, which is preceded by three texts: the foreword of Jeannine Meerapfel, the Akademie President, and essays from Werner Heegewaldt, the Archive Director, and Eva-Maria Barkhofen, the head of the architecture archive, and editor of this book.

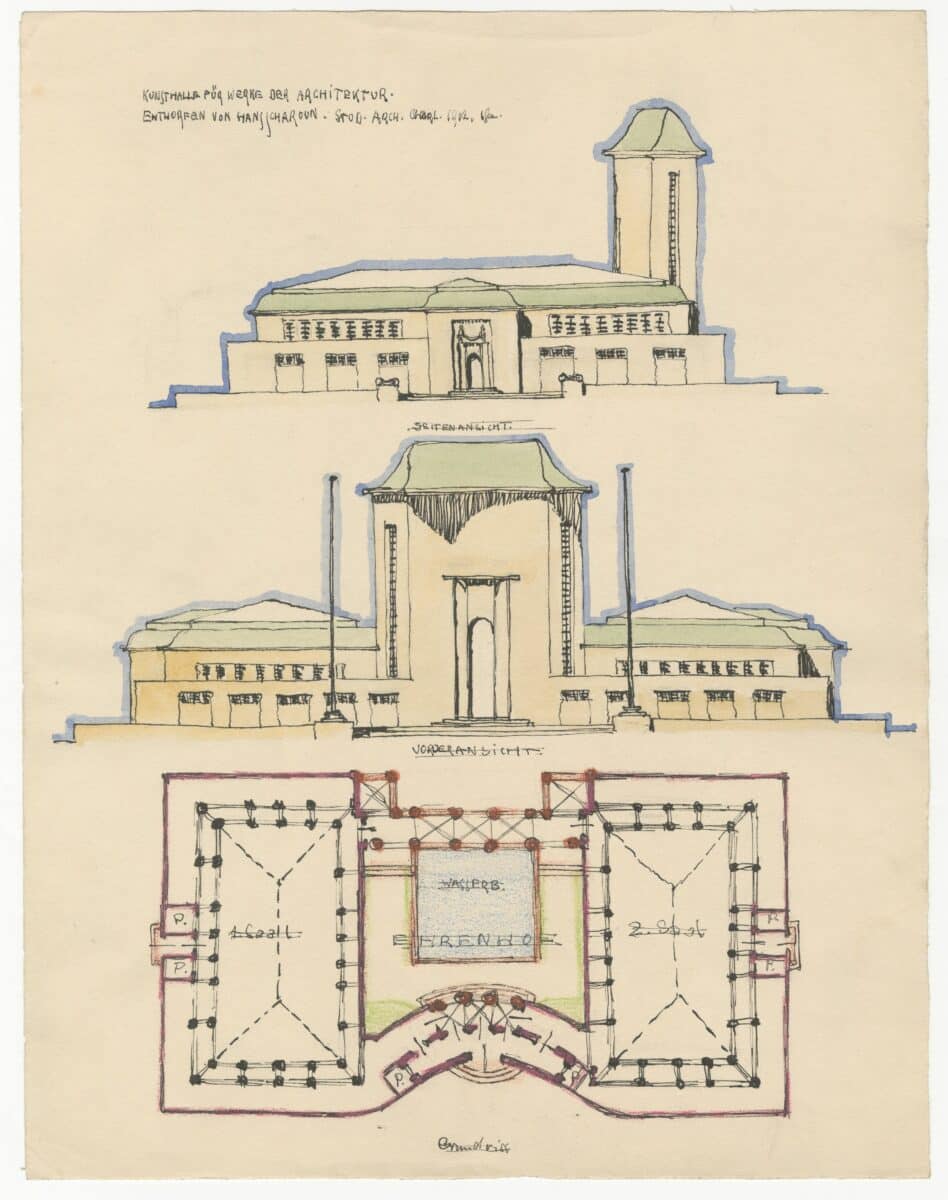

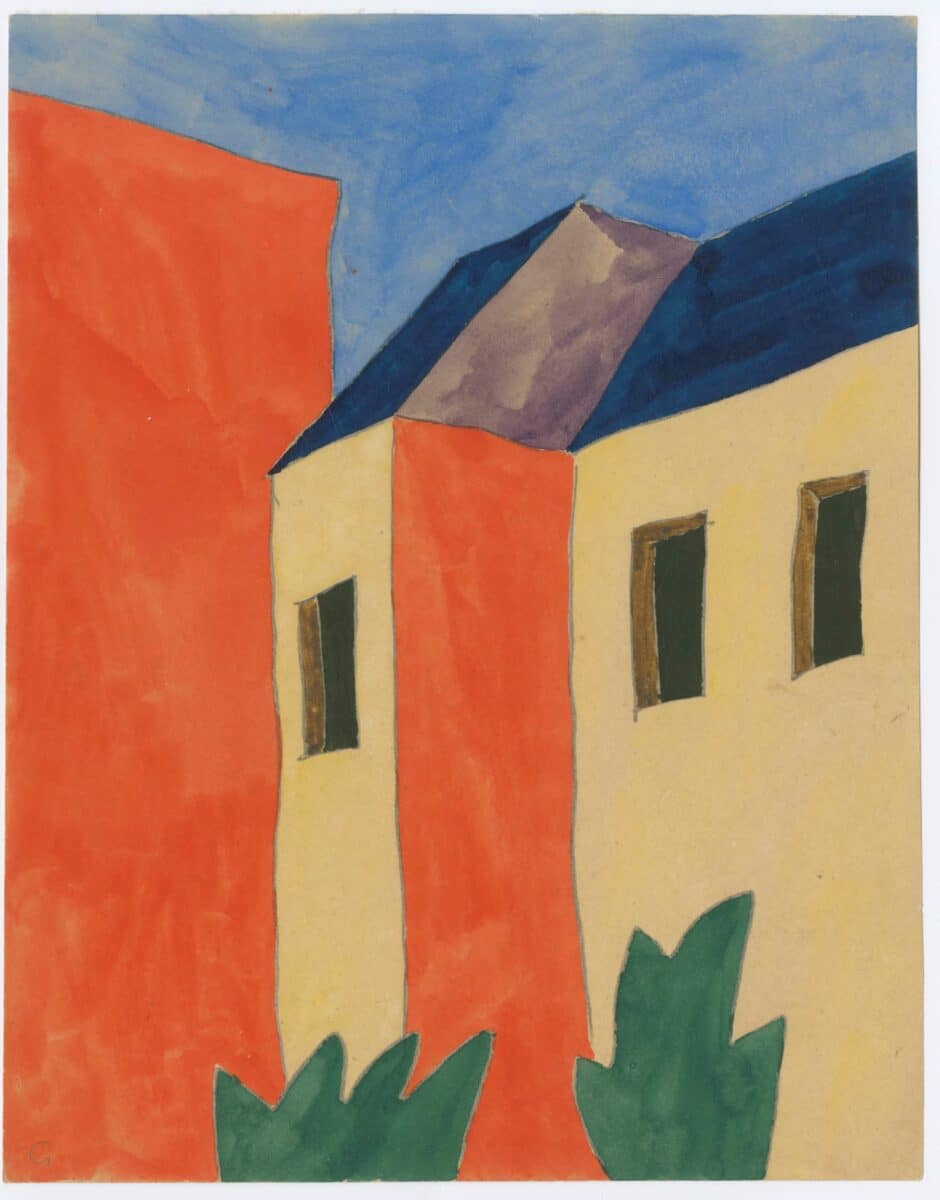

The 500-page catalogue of 71 individual archives and 63 collections is factual and impartial. There is a subtle hierarchy with which some are given a more extensive coverage than others. All are presented in alphabetical order, according to the same format. The archive entries consist of an information sheet with the architect’s biography and a brief description of the collection’s contents, followed by high-quality, colour, facsimile reproductions of selected material. The collection descriptions, while following a similar template, are more of a summary and can be read as an appendix.

The essay by Barkhofen is by far the most substantial and informative of all three. It outlines the institutional history of the archive, including the timeline of its donations, its locations, and cataloguing practices, and thus provides a useful historical context for its contents. Barkhofen is candid about the initially haphazard character of the collections, where material arising from architecture practice had been unsystematically gathered for two centuries. She is likewise correct in identifying the potential of the archives as a ‘comprehensive information pool for architecture history’. However, she stops short of questioning this lack of system and the imbalances that result from accidental amassing of material (no mention is made of the fact that out of 144 combined collections, less than five apparently feature women). The publication’s declared aim is instead to ‘vividly communicate what architecture may also amount to: architecture in miniature.’ With the abundant support of over 900 illustrations, it envisions the architecture archive as a selective and muted collection of beautiful objects. The book seems mainly conceived for the pleasure of beholding archival objects, rather than analysing them as evidence for understanding professional practice and its wider role in society. An assessment of the holdings’ historical importance is left to the reader, as the editor hopes that ‘architectural afficionados take pleasure in this and researchers feel moved to conduct further research’. The book’s curtailed scope also openly stated: ‘no critical appraisal of individual archives is put forward in this publication’. There is a whiff of missed opportunity about this. A couple of scholarly essays, themed so as to cut across the collections or analysing their content, would have gone a long way towards demonstrating the research potential of this architectural treasure trove. In the absence of interpretative or critical dimensions, the publication does little to dispel a firmly held association in the minds of the public between historical worth and aesthetic appeal.

Architecture archives are only at the beginning of their long mission to achieve diversity and social equity by changing their collection policies, prospectively as well as retrospectively. It will probably take decades for a bulwark of corrective, alternative, decolonising collections to build up. Nevertheless, the publications that highlight archival holdings are quicker on their feet. It is hoped, as the systematic description of contents increasingly moves online, that publications will assume more critical tasks. In holding a mirror to the archive, they also have the duty to reflect on its omissions, question its past, and thus inform its future.

Eva-Maria Barkhofen ed. Architecture in Archives: The Collection of the Akademie der Künste (2016) is published by DOM Publishers. Copies of the book can be purchased here.

Irina Davidovici is Director of the gta archives at the Department of Architecture, ETH Zurich.

Notes

1. Daniel M. Abramson, Zeynep Çelik Alexander, and Michael Osman, “Introduction: Evidence, Narrative, and Writing Architectural History”, in Aggregate, Writing Architectural History. Evidence and Narrative in the Twenty-First Century, University of Pittsburgh Press 2021, 3–16, p.11.