Connor Street: Made by Many Hands

3. Reclaim and Re-Use

The following text is the third in a series by architect Kieran Hawkins, Director of Cairn, tracing the design and construction of an extension to a Victorian House in East London, recounting the everyday realities of the project and, in the green text, the broader environmental issues incumbent on architects to address. The texts have been developed by Kieran from a talk first given during the Poetic Pragmatism symposium, organised by David Grandorge and held at Waterloo City Farm on 25 March 2023.

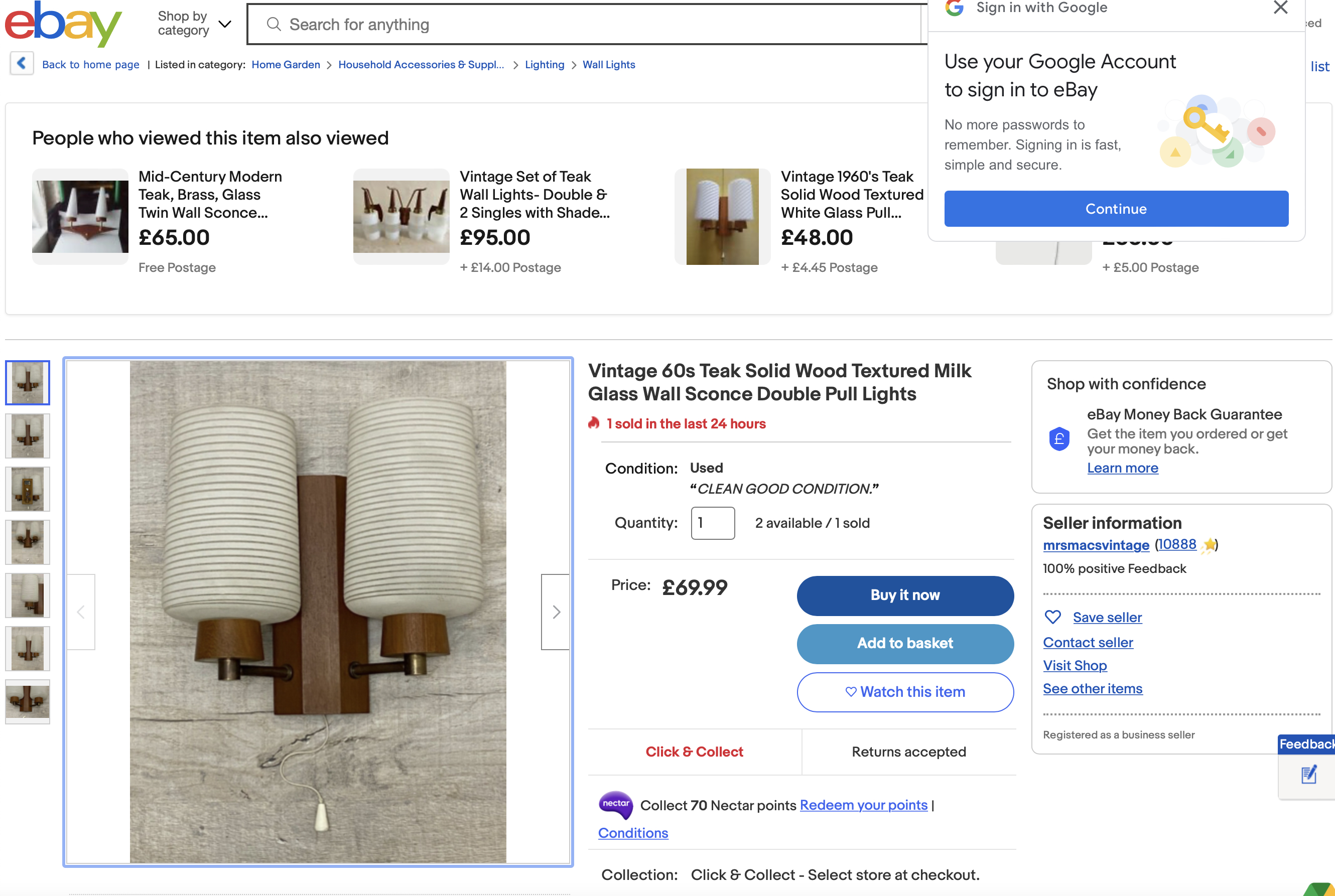

Throughout the project, fixtures, fittings and non-structural components were either reused from the client’s house or reclaimed from elsewhere. Salvage yards and eBay became primary suppliers. Dora and Danny were determined not to use new items unless it was unavoidable. As the architects, we had to release some aesthetic control and relax our grip on the design. I hope the project retains a cohesion through the framework we made for these items to inhabit.

In the design of house interiors, one of an architect’s most critical skills might now be to encourage a client away from consuming the newly manufactured. The scale of our waste crisis suggests we need to become very good at strategies for integrating reused items into coherent rooms.

Undeniably, this approach made the job more difficult for us and the contractor. No data sheets with helpful diagrams here. The bath proved to be particularly troublesome, as we wrestled with coordination between the tub, the old re-used shower, salvage yard taps that were lost in a box somewhere and delayed reclaimed tiles—a quaint illustration of much bigger challenges that we’ll face in the critically serious business of making buildings in a more ethical manner.

The specification here was driven by belief that minimising our impact on the living world matters more than having brand new fittings in each room. The clients initiated this approach and remained fully committed. It made a wonderful change from basing choices on social media lifestyle images.

It felt right that the site hoarding was decorated with children’s drawings from the neighbouring school. There was a generosity and trust in this suggestion by the contractor that fitted the ethos of the work we were doing.

Tolerance was essential and needed in both material and emotional contexts. Specification decisions were left unresolved far later in the process than usual. We had to allow questions to remain open longer than we felt comfortable with. This required a shared appreciation between client, contractor and architect that estimates for costs and time would just have to be good enough until items had been installed.

We are starting to learn how to leave more room for experimentation and the contingent. It is not easy balancing this flexibility with pre-build clarity and peace of mind in managing liability and risk. The bigger the project, the harder it is to leave this space. Maybe interior fit-outs, where consequences are less severe, can be kept under separate contracts to the rest of construction.

This approach led to several unexpectedly enjoyable areas of design. One example that we would not usually give too much thought was a bathroom sliding door. Here we reused an old leaf and architrave from elsewhere in the house. For it to fit the opening and receive suitable ironmongery it had to be lengthened and patched with some careful joinery, giving it something of a ready-made quality and a sense of satisfaction. Other items came with stories to tell and histories to imagine. The timber floor is reclaimed from Bow Magistrates Court, now laid below whirring mid-century Mediterranean ceiling fans.

What role do models and drawings have in this type of work? We modelled the project in Revit. Not because we were collaborating in BIM, but because we find it helpful to build the project digitally before it is built on site. With so many bespoke details and non-standard materials, it also helped in communication with the people making the building.

The informal form of practice on the project did not reduce the rigour of the information we made for design and construction. This project was all detail. We made every junction in 3D so we could be sure that we all understood it. Taking extra care because we were building differently.

We also made a physical model which gave me a confidence in the project that I find hard to hold if the design has no presence outside of a computer. And it is a joyful thing to share with the client and as a focus for conversations.