Connor Street: Made by Many Hands

4. Assembling The Frame

The following text is the fourth in a series by architect Kieran Hawkins, Director of Cairn, tracing the design and construction of an extension to a Victorian House in East London, recounting the everyday realities of the project and, in the green text, the broader environmental issues incumbent on architects to address. The texts have been developed by Kieran from a talk first given during the Poetic Pragmatism symposium, organised by David Grandorge and held at Waterloo City Farm on 25 March 2023.

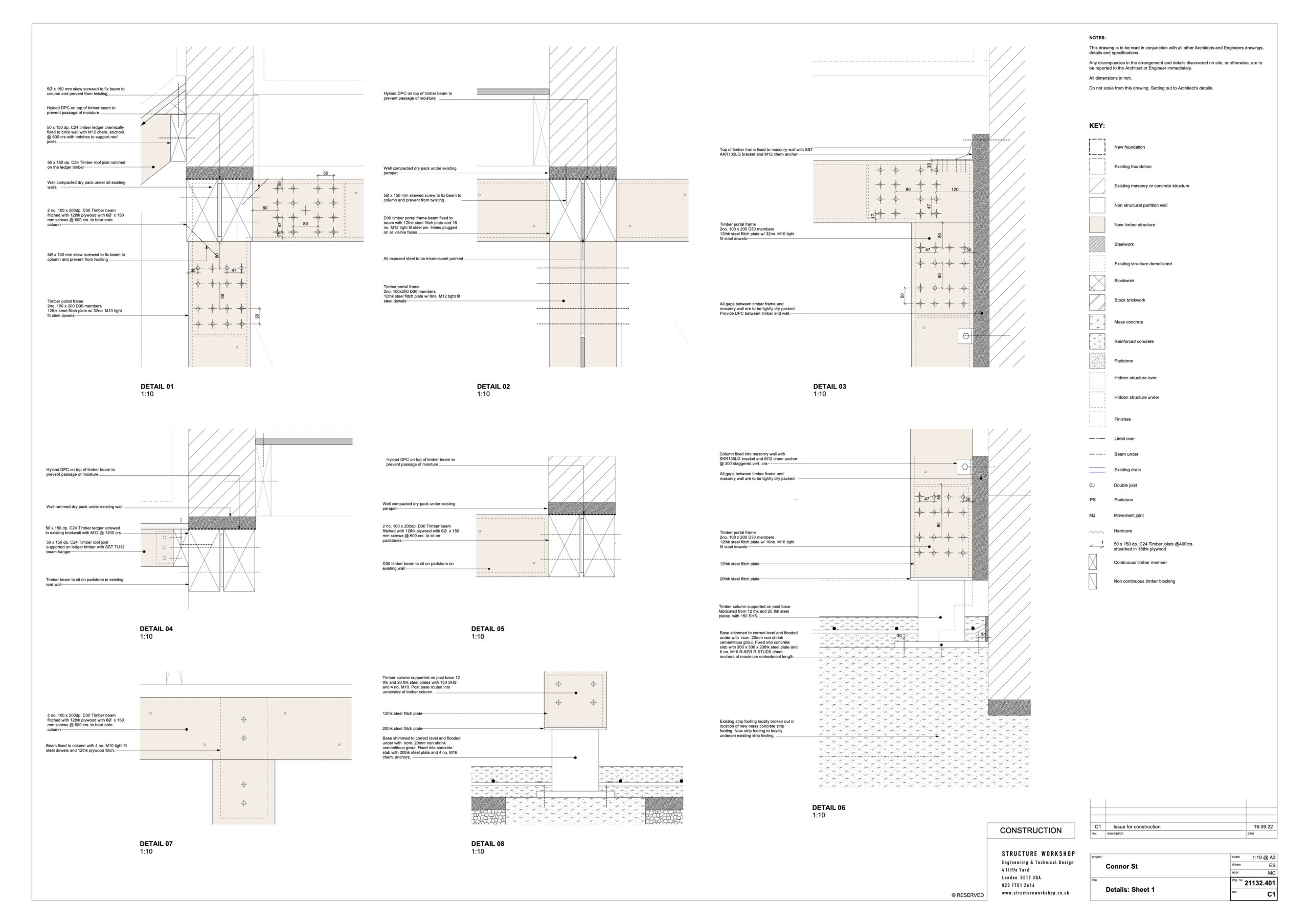

The primary structure is a timber frame supporting the loads of the existing brick house and the new additions. The layouts were set according to the timber spans, and the frame was always intended to be celebrated as a key visual component of the interiors. Steel was used sparingly, forming footings and flitch plates at key connections and allowing demountable bolted connections.

There doesn’t seem to be an easy answer to the question of what we should build with now, but as a simplistic game I like looking at a material’s past and imagining its future. Finding those that have the lowest production emissions and destructive extraction, and that offer most hope of generating little waste when no longer needed in the building, either through their longevity or reusability.

Playing this game, there are many materials readily available that score higher than the conventional options doggedly dominating the UK market. Alongside vested political and economic interests, much of this lag can be traced to a fear of liability, and reliance on reassuring certificates and standards that cost a lot of money to obtain.

We specified sapele for the frame, which is a species we’d used for exposed roof joists on previous projects. In hindsight I’m not entirely comfortable with the choice, as these trees are harvested in far away tropical Africa. It’s all FSC certified and was transported by boat, but this does not really put me at ease. I’ve read more now than I had then, and I’m more aware of the likely environmental and social costs at sites of extraction and processing.

I am learning to be more careful with specifications. A focus on embodied carbon needs to be combined with consideration of damage caused by the supply chain’s broader impact on living systems. The complexity and opacity of this is daunting.

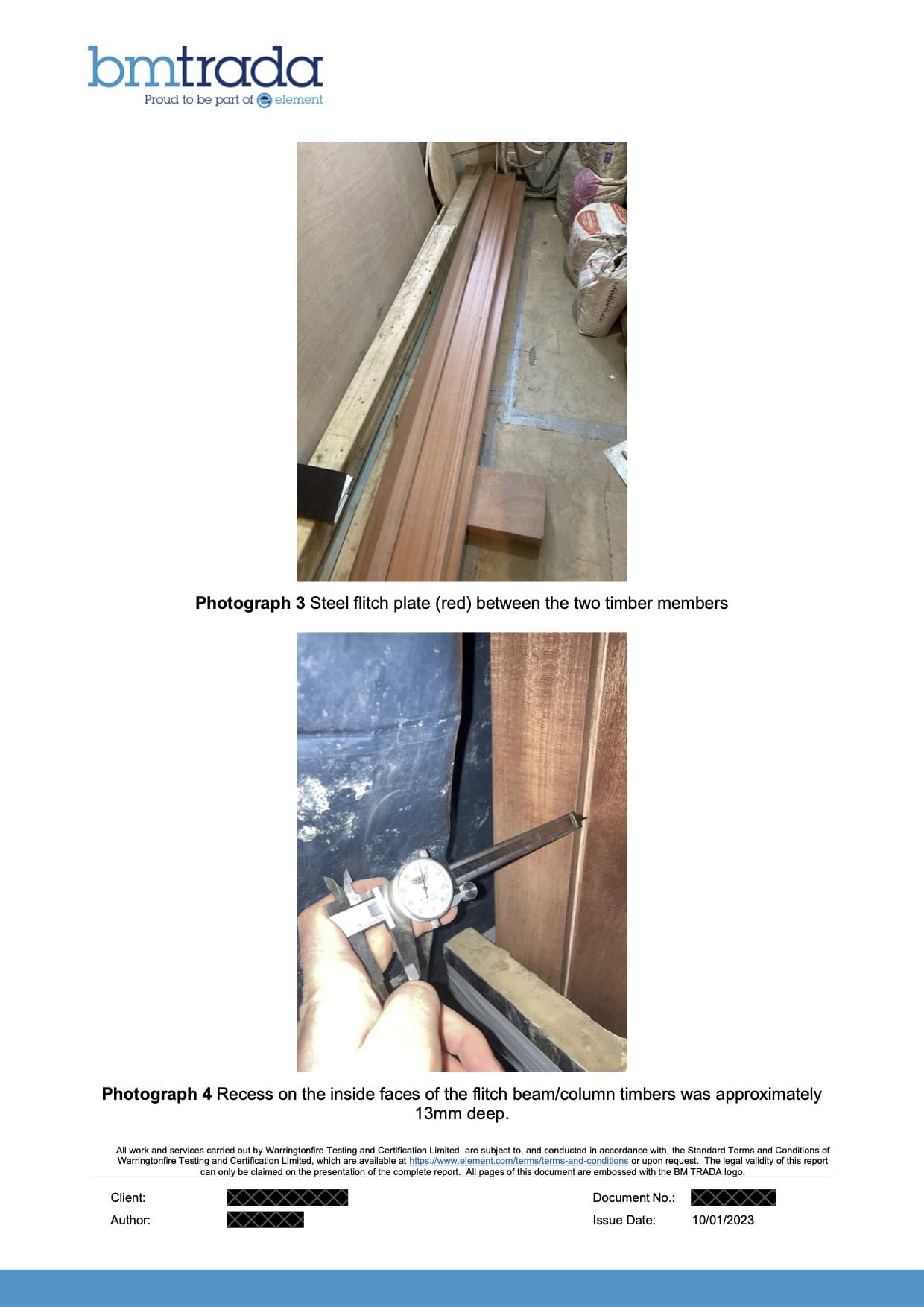

Using hardwood for load-bearing columns and beams was new to us and we didn’t appreciate the level of certification required. Structure Workshop had prepared lovely details and calculations allowing for D30 graded hardwood. Sapele, however, has no standard strength capacity in the UK’s grading system and confidence in the wood from the contractor and merchant was not enough for such an important component. By the time this came to light all the timber was already paid for and on site and a lot had been installed, but the engineer was unable to sign off the work.

Despite many hours on the phone and email, the only way we found of resolving this was to commission BM TRADA to come to site to grade the timber for us. Happily, their report confirmed the sapele was D40 grade: even stronger than required. A relief. There were a few nervous weeks as we waited, though they would have been a lot more nervous on a larger project. There is much to be said for learning through small acts.

Post-completion insurance for new buildings puts huge pressure on design teams to use standardised products and pre-approved details in the highly litigious construction industry. We may not always be able to do things differently, but we do need to be aware of how damaging this business-as-usual practice is.

Standardised products tend to be those that are most heavily processed, generating harmful by-products and proving to be the hardest to reuse or repair. We might be reducing immediate risk to our businesses, but the cost of making our buildings this way will be painfully high.

I know how privileged I am to work on a rare project like this. It comes with an obligation to develop approaches that can be used on more mainstream construction sites.

– Gordon Shrigley