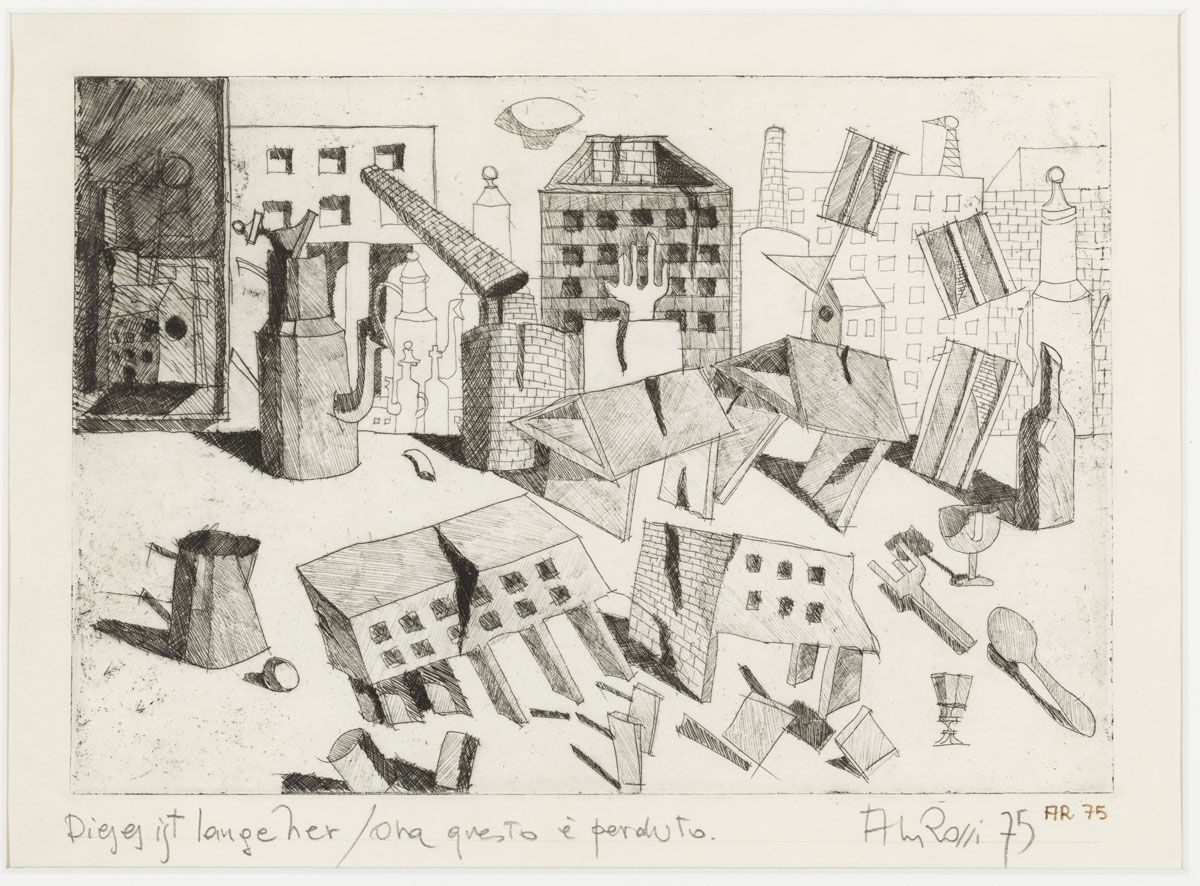

Aldo Rossi: Dieses Ist Lange Her/ora Questo e Perduto

Looking at This was a long time ago/now this is lost, as well as other drawings in Rossi’s unofficial collection of l’architettura assassinata, brings to mind the image of a feast. The scenes are funereal indeed, but they hold a festive aura, as if a celebration had just taken place and the corpses of the actors that took part in it are still there, still fresh. The event is portrayed with theatrical drama and exquisite wit — it’s an act performed at il teatrino scientífico, a play finishing its second act. We see cups, we see bottles, and imagine wine and camaraderie. We see an impish little flag, which is perhaps about to fall over, and chatterbox percolators the size of buildings. We see clunky tableware that has been used too many times — but most of all we see broken architecture as the dead host of this elated gathering. The scale matters not, it is merely a game.

The whole mess of the drawing feels erratic as much as it does naïve. Rossi, somehow, manages to simultaneously depict both the melancholy of death as well as the childlike commotion of the Mad Hatter’s tea party. Maybe ‘madness’ is our inadequacy to endure the transformation. The association between innocence (and its loss) and Rossi’s work has already been well-discussed. Considering that he made these drawings while working on the San Cataldo Cemetery proposal in the early 70s, and the fact that just before starting the design he had a car accident in which, in his own words, his ‘youth reached its end‘, it’s not hard to imagine what Rossi is trying to express in the drawings: this death of innocence, and the drama of youth’s ending.

This, of course, is not to be taken as a narcissistic, vulgar fear of growing old. The transfiguration, the materiality of this loss wouldn’t hold such reign over our imaginations in viewing this drawing, as well as Rossi’s architecture, if it grew from such triviality. Our experiences matter, and both the civil and individual devices we use to confront and to process them are subject to the same gradual disfiguration our memory undergoes. If we can agree that poetry is not only a way to cope with reality but also plays a part in the construction of reality itself, in particular with architecture, then we might approach the idea that the same ending awaits all material manifestations of specific, albeit diverse, sets of realities over time. Poetry is somehow not eternal, but always present.

L’architettura assassinata is no more than the relationship between a civilization and the time that has been given to it. In Rossi we find an underlying struggle between the architectures of the city that have borne transformation throughout history, their permanence, and the ultimate unrecognisability to which all forms are bound. It is this contradiction that is rather comically relived in the scene.

On a trip Rossi and two of his colleagues took down to Campania, shortly after submitting a competition entry together, they reached a hill upon which one could see the ruins of a castle. ‘It is as if it has always been there’, Rossi said. There’s a degree to which memory can be kept, though it cannot always keep the essence (or poetry) with which an object or action was realised. We persist in the exceptions, and hold feasts for ourselves so that our passions don’t die unaware of themselves. We are compelled by the shattering of all forms and the oblivion of their repetition to watch our steps more closely, because no matter where we might be, an architecture may appear to us, like a vision, standing next to a road, at the end of a long drive, or in the middle of the city – so we may wonder about the life in it, and we may hear the rattle of plates and rushing steps, or the mourning silence of a wake yet to pass. During his hospitalisation, Rossi said that ‘[I] thought of the past, but sometimes I did not think: I merely gazed at the trees and the sky.’ So what is there left to ponder on other than the stroke of an emotion, the flash of it and instant fading.

Jaime Tillería Durango is currently focusing on a project for the divulgation of the geography, the cities and architecture of the equatorial Andes.

This text was submitted to the General Archive category of the Drawing Matter Writing Prize 2021.

– Jesse Reiser