Writing Prize 2021: Live My Drawings

Prologue: Panic! at K’s office

Location: K’s office, University of Sheffield, Arts Tower

Characters:

Tutor: K (calm, knowing)

Student: Me (facing an existential crisis, encountering a creative block, second-year hysteria… you get the idea)

Brief: To design a library

I am fascinated by the heterogeneity of our experience of built and natural spaces, and of those which lie between such categories. It is the idea that components of our architectural sphere – buildings, cities, and landscapes – are more than their physical constituents: that space can tell a wider story. To formulate and narrate this story is a Herculean endeavour, and during this project, I fell prey to the ever-tempting habit of data hoarding: lengthy interviews, countless precedent visits, and much introspection. My mind was left plump with insight, drawn upon years of recollections and reflections from myself and others, as well as an acute sensorial awareness from visits to the various case studies on my checklist.

This research was drafted into a complex narrative, stored in my mind. All that was left to do was to translate on to paper. But, beleaguered by the ‘Holy Trinity’ of plan section elevation that architectural education had instilled in my practice, I swiftly reached the end of my tether. After surpassing the nth-iteration of work, the results remained stubbornly reductive and soulless. I came to see stairwells and toilets as the nemesis of artistry. How could a powerful, personal experience find itself so offensively simplistic and crudely functional in presentation?

‘All my hard work was for nothing’, I lamented.

K reclined confidently with his hands folded, apparently unfazed by my outpouring. ‘Not everything can be represented spatially,’ he said simply, ‘you know that.’ He gestured to my laptop, that wretched, long-suffering piece of hardware that had endured my torment for weeks on end, endlessly splining, trimming, and rotating lines. ‘Get off the computer. Live your drawings.’

Some years later, I found myself immersed in Architecture Depends by Jeremy Till, who affirmed my ivory tower syndrome and my struggle in reconciling the chaotically contingent. ‘Mess is the law’, he writes. I recalled two instances from my earlier, less self-conscious years in education when I worked to translate parts of my seemingly intangible inner world into something evocative and physical.

The low-tech VR experience

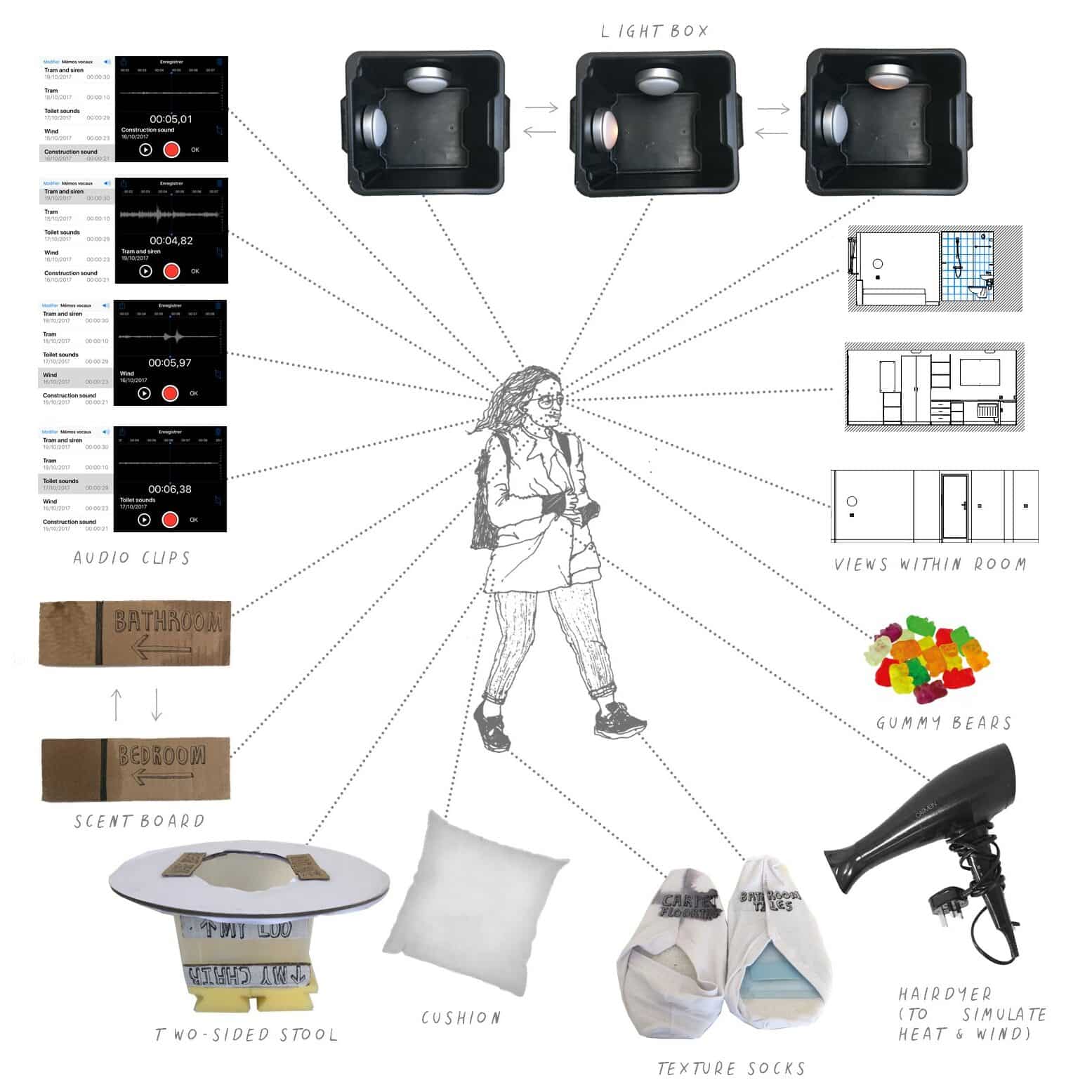

A diagram of my sensory installation of my room

In a first-year assignment to depict my bedroom, I wondered if, in a confined, personal space, we gain a heightened awareness of our non-visual senses. I tried to respond to Juhani Pallasmaa’s appeal to restore humanity in architecture through a mindful refocusing on the sensory and sensual experience of space. [1]

I tested this idea by setting up a sensory installation in my room. I understood this space through the lens of ‘hardscapes’ and ‘softscapes’. The bathroom was a place of coldness, hardness, and wetness. Its tiled floor was smooth and unyielding, its surfaces metallic. In contrast, my bedroom had a warm, gentle embrace. My workspace sat somewhere in between with solid wood surfaces but also an upholstered chair. I set out to gather a collection of wearable objects, tactile aids, audio clips, a scent board, and a bag of sweets. On a college student’s budget, this entailed:

- Salvaging scrap cardboard from friends’ Amazon deliveries.

- Rubbing shower gel onto the cardboard.

- Measuring my toilet seat for the first time.

- Waiting at my window for the drilling noises of an adjacent construction site to restart.

- Countless trips to Poundland.

In all, the set-up cost no more than a ticket to my local nightclub (and was perhaps as sticky). The installation was a low-tech, low-cost ‘virtual reality’ representation of my room. I provided the following instructions:

To get a sense of being…

At my desk: Sit on the soft side of the two-sided stool, turn the hairdryer to ‘hot’, wear the ‘carpet flooring’ side of the textured socks, and snack on the gummy bears provided. Listen to the sounds of construction noises.

On my bed: Rest on the mini bed and pillow, turn the hairdryer to ‘cool’, smell the ‘duvet’ section of the scent board. Listen to the audio of billowing winds.

In my toilet: Sit on the hard side of the two-sided stool, wear the ‘bathroom tiles’ side of the textured socks. Listen to the audio of bathroom sounds (flushing, the taps, and the shower running).

This performance was met with laughter at my next crit, which I presumed was in good humour, kindled by its off-beat, low-budget nature. In all, the work was intended to challenge our understanding of a drawing as a two-dimensional visual image.

Territory, movement, memory, memento mori

My second study took place as part of a project to design a bicycle parking station. It was to be a mapping exercise carried out with my friend James. The cartophile in me rejoiced.

We were inspired by the Situationists’ playful, disruptive, and contingent nature of impromptu urban explorations. The most famous Situationist map is likely Guy Debord’s plan of Paris, produced through a process of ‘détournement’, in which scale cartographic maps are broken down into distinct areas, and reconstituted as psycho–geographical maps to reflect the flows of energy between them.

Together, we worked under the premise that our perception and memory of space can be developed incrementally, both from long journeys and contemplations, as well as ‘patched’ together from haphazard and varied encounters.

The study aimed to understand the city from the perspective of a cyclist and how they might navigate a landscape. In true Situationist spirit, we fixed GoPros onto our bikes, downloaded a route tracking app onto our phones, and embarked on a 3-day dérive around the site and surrounding areas to document observations and collect memorabilia. [2] We then exported 15 hours of footage as individual frames on a video editor, and printed and cut these out (thank our lucky stars for concessional printing). We also recorded our heart rates as they rose and fell according to the topography.

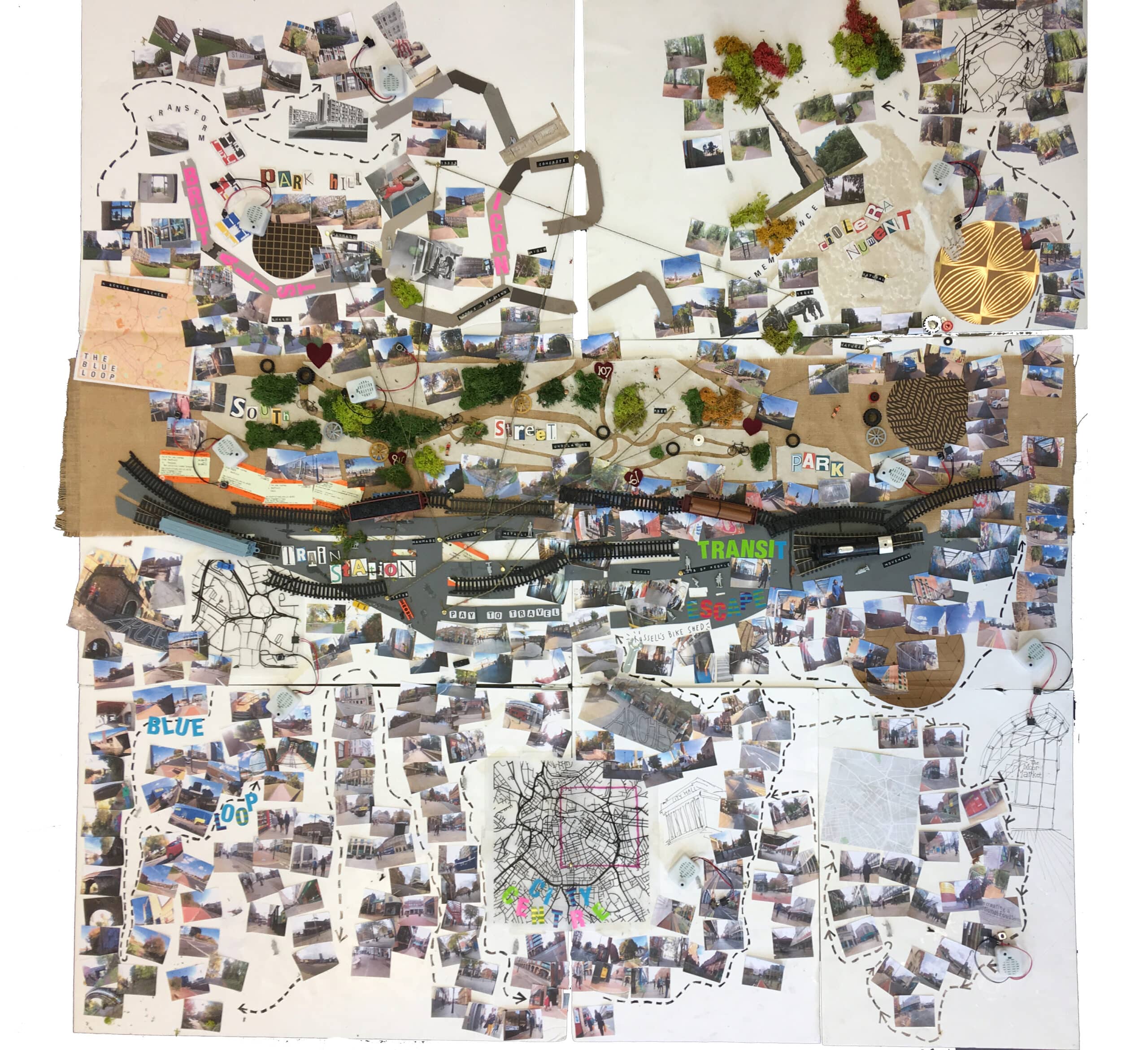

A subjective map developed with my friend James of a site in Sheffield.

During this exercise, we found features of the city a cyclist might avoid or find challenging, exploring the opportunities and risks they might take, and considering the psychological conditions that might develop within their consciousnesses. This understanding aligned with Henry Plummer’s proposition that humanity’s use of its free will is vital for self-actualisation. [3] We also discovered some unexpected needs, such as charging points, drinking water, and public toilets, and observed how non-cyclists (pedestrians and drivers) respond to cyclists.

Afterwards, we began building our base map, dividing the site into seven distinct areas: Park Hill, Cholera Monument Grounds, Sheffield Train Station, Park Square Roundabout, South Street Park, The Blue Loop, City Centre. We traced out selected elements of each area, and applied the materials and textures we felt best reflected their character: lace for the ethereal aura of the monument grounds, uncoated grey card for the béton brut of the Park Hill flats. We taped on scavenged train tickets and leaves and glued down our printed video frames and audio recordings.

Detail of the subjective map.

We then delved into the history of the site and searched image archives. From daguerreotypes of men with horses and carts whisking away nineteenth-century cholera victims to technicoloured polaroids of past Park Hill residents, the images we collaged onto our map evoked in us a sense of nostalgia and reminded us of the passing of time. Over coffee, we contemplated the mortality of architecture and, in turn, of ourselves, as opposed to the seemingly eternal nature of cultural memories and lore. For the final stage, we connected themes across areas, such as construction dates, materiality, and programmes with yarn to imitate neural connections. The map was a union of two subjective truths, and pregnant with what Donna Haraway calls ‘situated knowledge’. [4] Debord would have been proud.

Epilogue: Get off the computer

Pallasmaa is critical of the use of digital technology in creative work but acknowledges its utility in architectural production. In both the studies described here, digital technology was used, but it only acted as a conduit for the sensorial experience rather than the experience itself. As it turns out, the suggestion to ‘live my drawings’ was an encouragement to not only explore new methods of design and representation but to also return to a more curious, hungry self that lives bravely and hunts voraciously for meaning. This self was momentarily lost in the reductive neatness of digital production but found once more through imagination and sensorial engagement.

Ying Xuan is a structural engineering and architecture student at the University of Sheffield with an interest in participatory practice, designing for wellbeing, and sustainable development.

This text was selected as the winning entry in the Student Autograph category of the Drawing Matter Writing Prize 2021.

Notes

K is a tutor that I trust and respect.

- Juhani Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses (John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, 1995)

- Debord defines the dérive as ‘an unplanned journey through a landscape, usually urban, in which participants drop their everyday relations and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there’.

- Henry Plummer, The Experience of Architecture (Thames and Hudson Ltd: New York and London, 2016)

- Donna Haraway, Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective (Feminist Studies, Vol.14, No. 3: Maryland, 1988)