Cartographies of the Imagination

Six anchors in a sea of maps

– Kirsty Badenoch and Sayan Skandarajah

Drawing place is illusory. Maps may begin as transcriptions of a worldly order – a semblance of truth and objectivity – but in doing so, become acts of world-building that both belong to and are entirely removed from their starting point.

In 2019, we first visited Shatwell Farm in the perusal of a potential project that was to become the Cartographies of the Imagination festival of drawing. At that stage, all that had been developed was the name. We felt this phrase fitted the ethos and sensibilities of our own drawing investigations: the re-enactment and representation of the landscape and urban terrain that is impossible to fully capture. We were interested in the capacity of drawing to provoke in the mind’s eye a place that becomes, through its own representation, an entirely different place, navigating between the real and the imaginary.

This loose thread was our starting point. The initial and subsequent visits to the archive, alongside discussions with the Drawing Matter team helped shape and form what exactly Cartographies of the Imagination meant for us. We knew that we wanted to open the project to specialists in a wide range of fields such as architecture, landscape, painting, geography, sound, sculpture, technology and film, to discuss contemporary perspectives within alternative practices of cartography.

However, it felt important to also moor the project, to define its terms and develop an inner structure from which our evocative and expansive themes could circle and respond. The exploration of the Drawing Matter archives was a search for such anchors in the rich historiography of architectural drawing – a series of buoys for our own cartographic journey.

The idea of selecting just a handful of pieces within the vast collection of treasures at Drawing Matter at first seemed unthinkable. But as we began to examine the drawings and unpick our project, clear trends and themes started to reveal themselves. The ideas of retracing a journey, capturing the immaterial, unravelling a narrative, remembering place and reconstructing imagination were all discoveries made in the archives that shaped and formed our project. What follows are our own interpretations of these discoveries, these anchors in a sea of maps that became Cartographies of the Imagination.

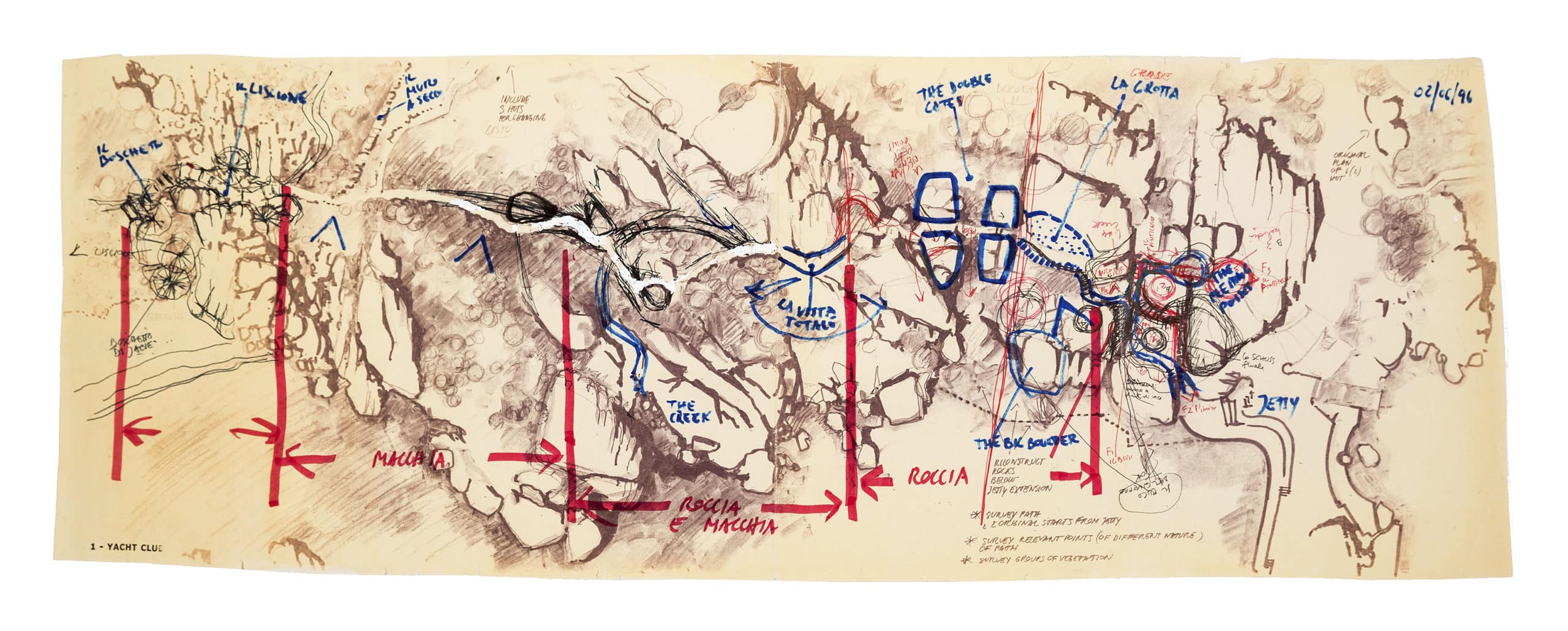

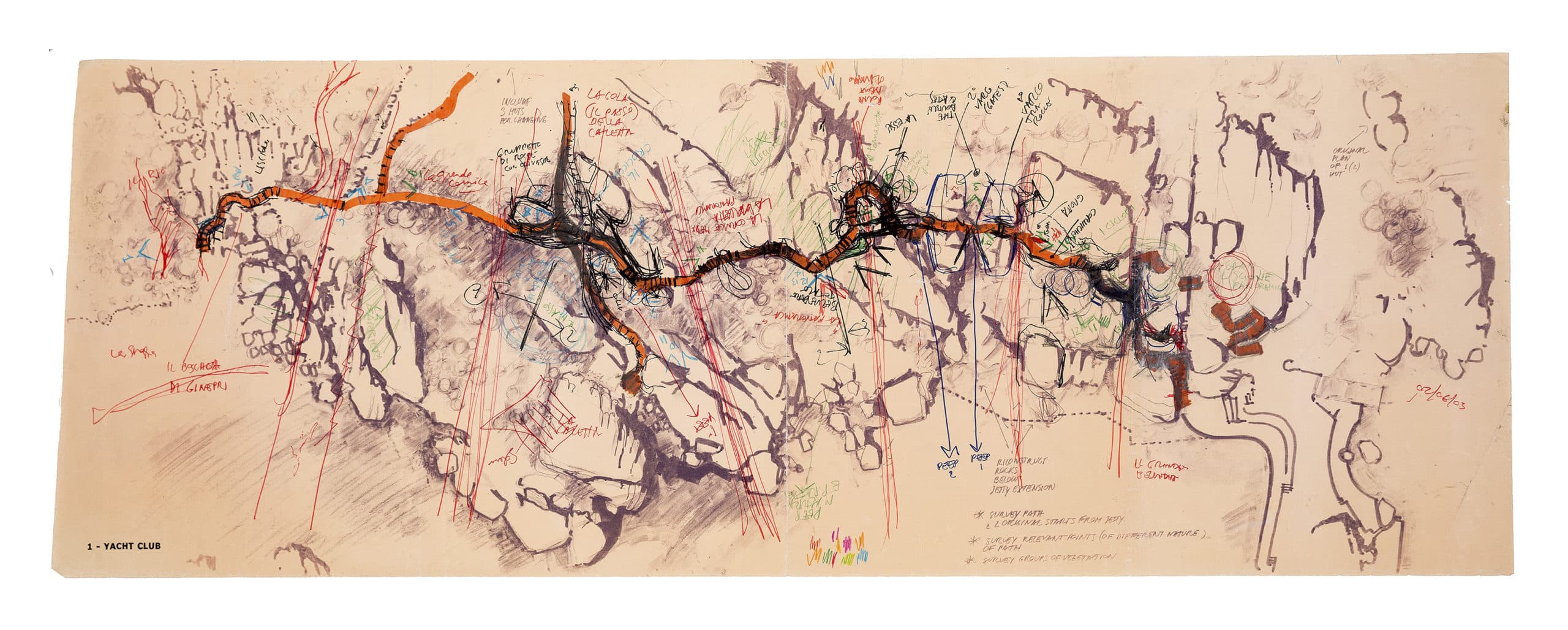

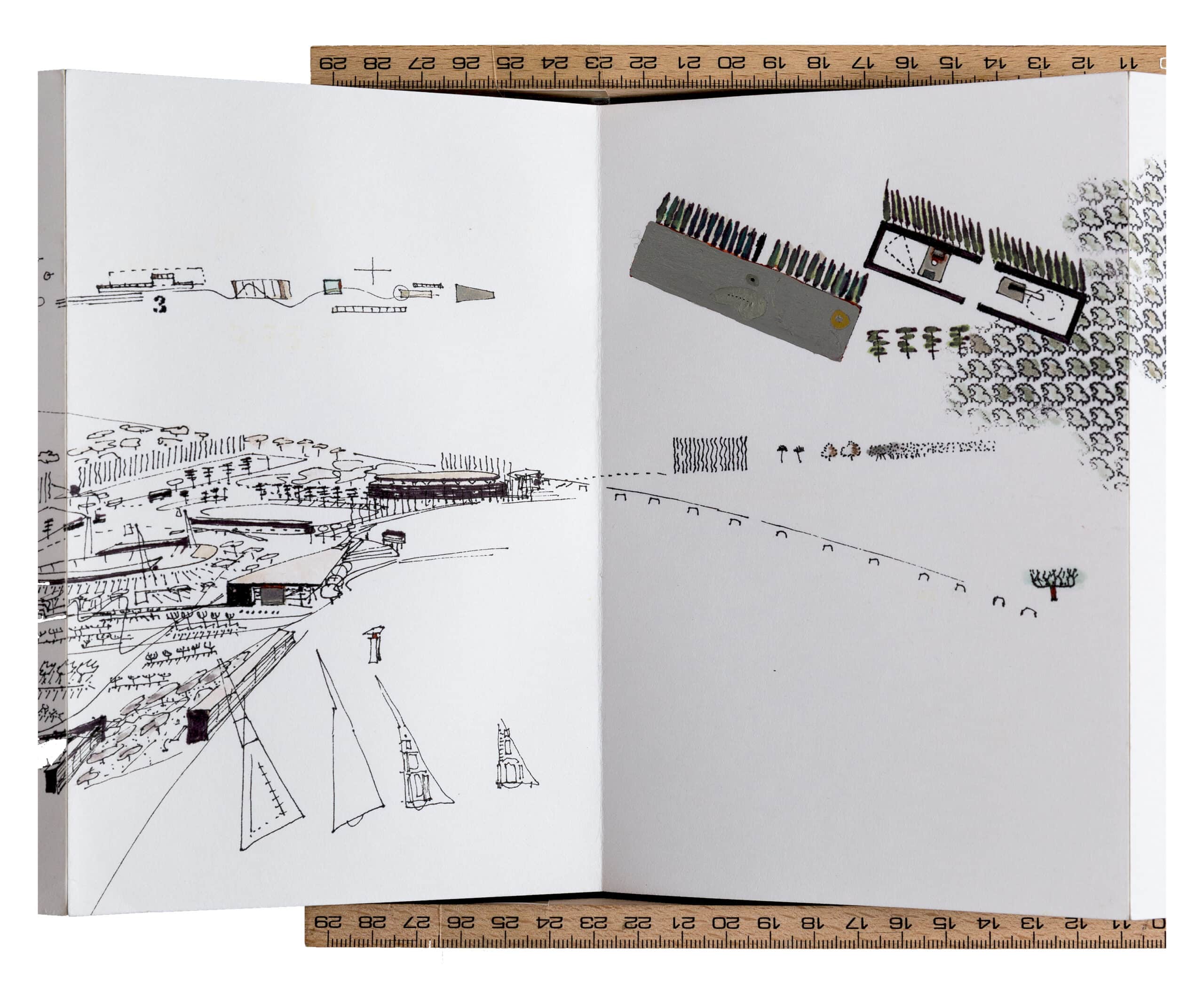

Alberto Ponis – Yacht Club Path

Alberto Ponis picks his way between the rocks. Unfolding a large, already yellowing transparency from his pocket, he marks a node with an orange highlighter and asterisks it. He draws out of necessity. The official maps of the Sicilian Coast are not sufficient; projected at too large a scale and without an understanding of how bodies of granite and human might relate to one another. They don’t notice where erosion has mislaid part the cliff, or where young tree roots are pulling away a small crevasse – that has expanded since last month.

Ponis measures the gaps between the stones with his feet, gauging where a bicycle, a donkey, a delivery man, a scaffolder might pass and triangulates the points where a wall could touch down upon a bolder – how a hard line might meet a soft one. He photocopies the same base drawing over and over for each walk, each copy dulling his original sketch in apt reflection of the timeworn geological formations. Fast marks over slow lines, when stacked, his maps of this coastal walk would be almost as tall as the cliffs themselves. He brings each one back to the studio, to his client’s house, to the building depot, to discuss how a new architecture might fit into the old. Alone, each is not precious; never complete.

These drawings not only describe walks but are in themselves walks, tracings of the land trodden and re-trodden. Unfolded, traversed and reiterated. These are maps drawn though the journeys they have embarked upon.

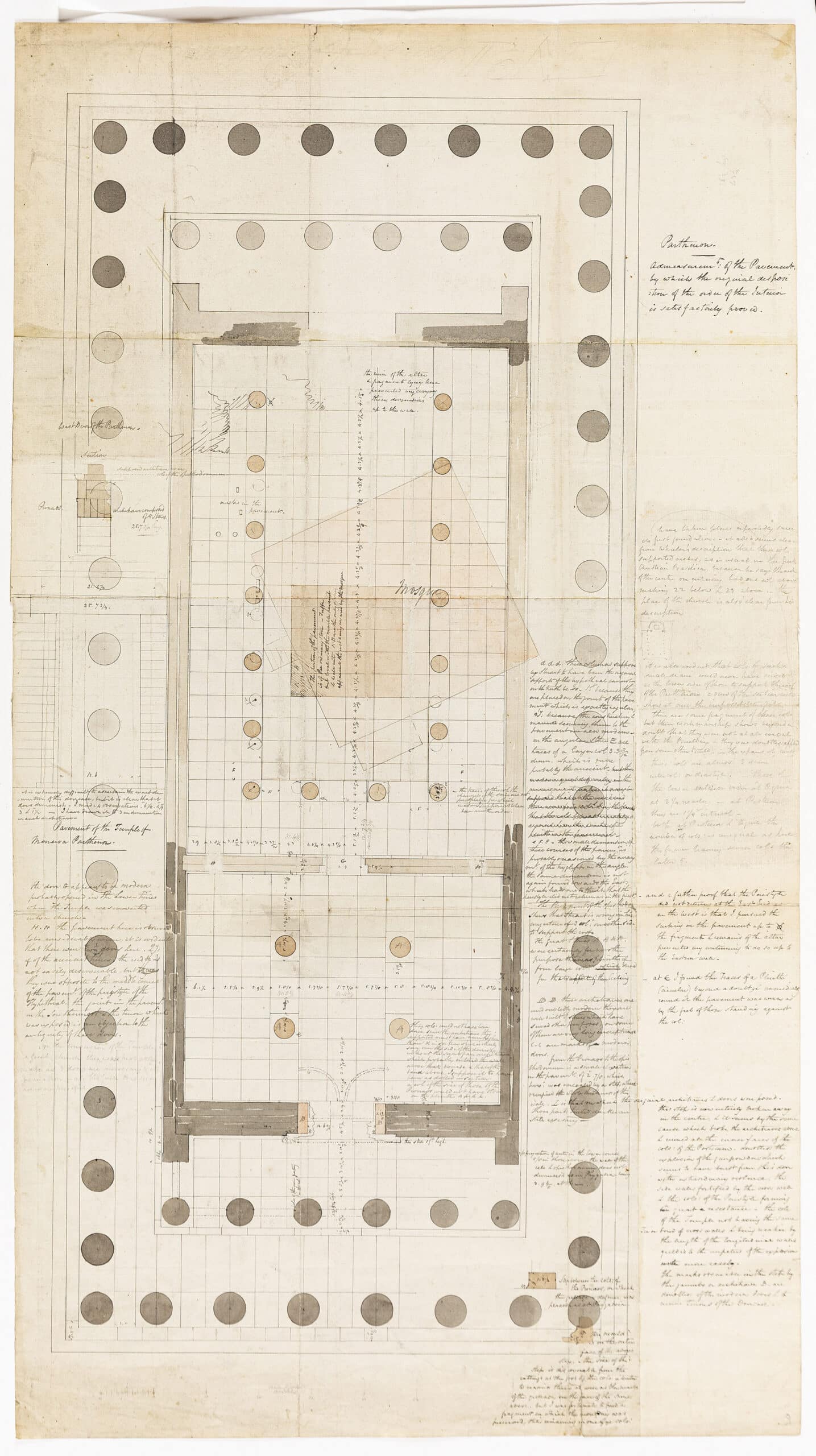

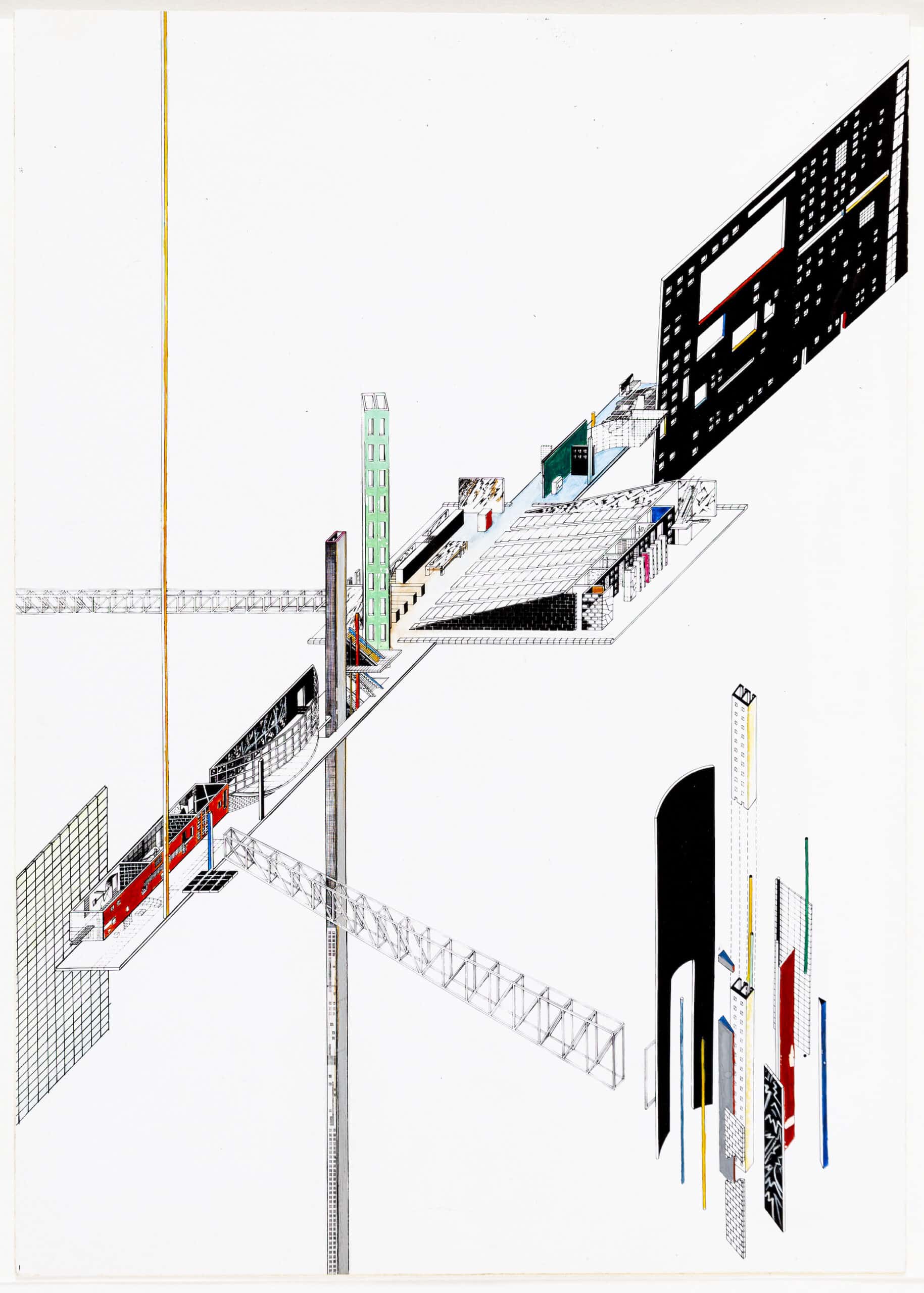

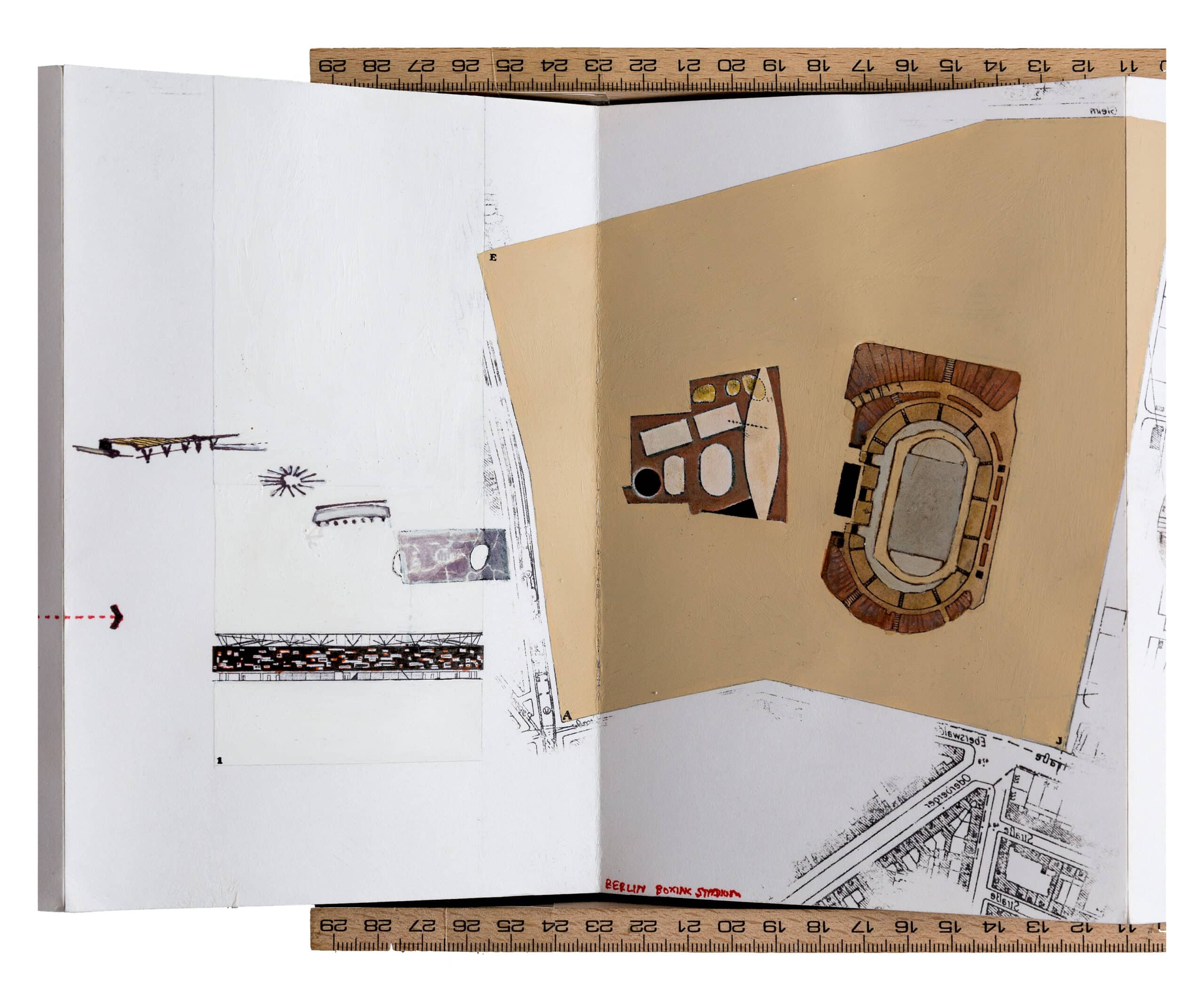

Charles Robert Cockerell – Plan of the Parthenon, Athens & Zaha Hadid, Axonometry: The Ambulatory and its connections

When you arrive atop the Athenian Acropolis, you would be forgiven for thinking the colossal columns of the ancient Parthenon had been set there since the beginning of man. Similarly, you might be mistaken in thinking a plan is planned.

It is not so. The temple was built upon earlier forms of itself over multiple eras, each carrying small traces, realignments and references to the last. Charles Robert Cockerell’s survey drawings of the site of the Parthenon fundamentally questioned the solidity of marble. His pen excavated, tracing his movements as he circled the site – drawing and digging and erasing and rewriting a history assumed before to be fact.

One hundred and sixty-six years later, Rem Koolhaas, Elia Zenghelis and Zaha Hadid rewrote a future for their own temple. Employing the surrealist method of the ‘exquisite corpse’ in their design for the Dutch Parliament building, they portioned a series of ‘limbs’ between the three of them, each undertaking a section of the whole building, unknowing of the other’s work. The designs were later combined into one single piece, an incoherent set of transformations that embodied the chaotic history of the area, connected at pre-determined contact points.

These pens hold within their method a million walls and windows, they are trowels for unearthing, microscopes for inspecting, and crystal balls for foretelling.

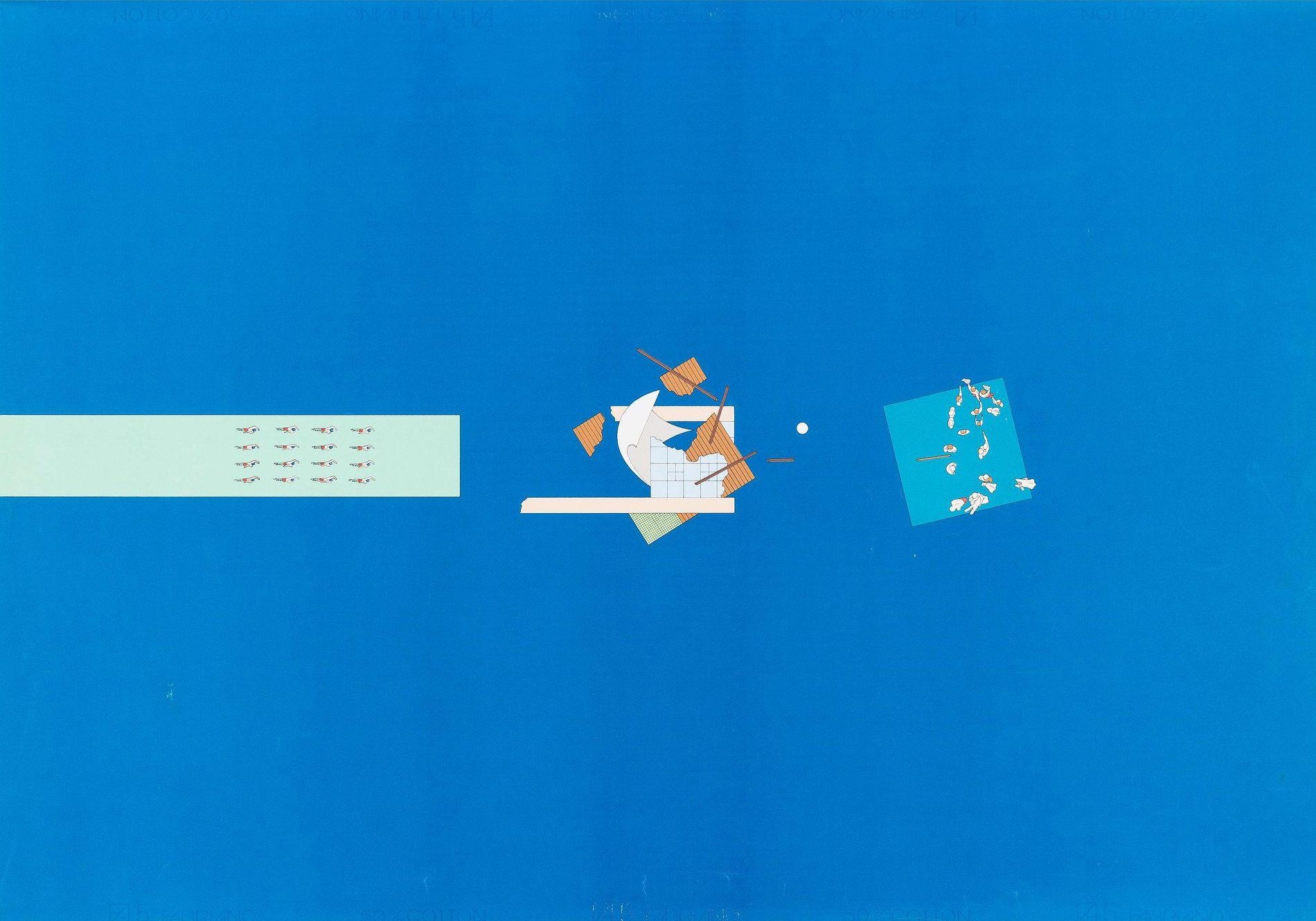

Madelon Vriesendorp, Trial proof, The Raft of the Medusa

It takes sixteen synchronised swimmers forty years to propel their floating swimming pool across the Atlantic, back to New York. To undertake this travail the swimmers must swim backwards, moving progressively away from their destination. Their pool is the size of a Manhattan block on plan, only it is a watery hole of emptiness. The swimmers do not see the city as it looms toward them. Ahead (or is it behind?) lies the inevitable catastrophe of the crash – upon docking, the pool shatters the much-too-small pier and ploughs into the city. Beyond that, its own shipwreck is visible for a brief moment before sinking under.

Along the x-axis, the drawing compresses time – depicting the event at three sequential moments – then, now and later on. Along the y-, it moves from fiction to fallacy, shifting scale from the human to the urban to the oceanic. Madelon Vriesendorp and Rem Koolhaas narrate a fictive world between his writing and her drawing, an exchange of Chinese whispers that anticipates a new and timeless collaborative world.

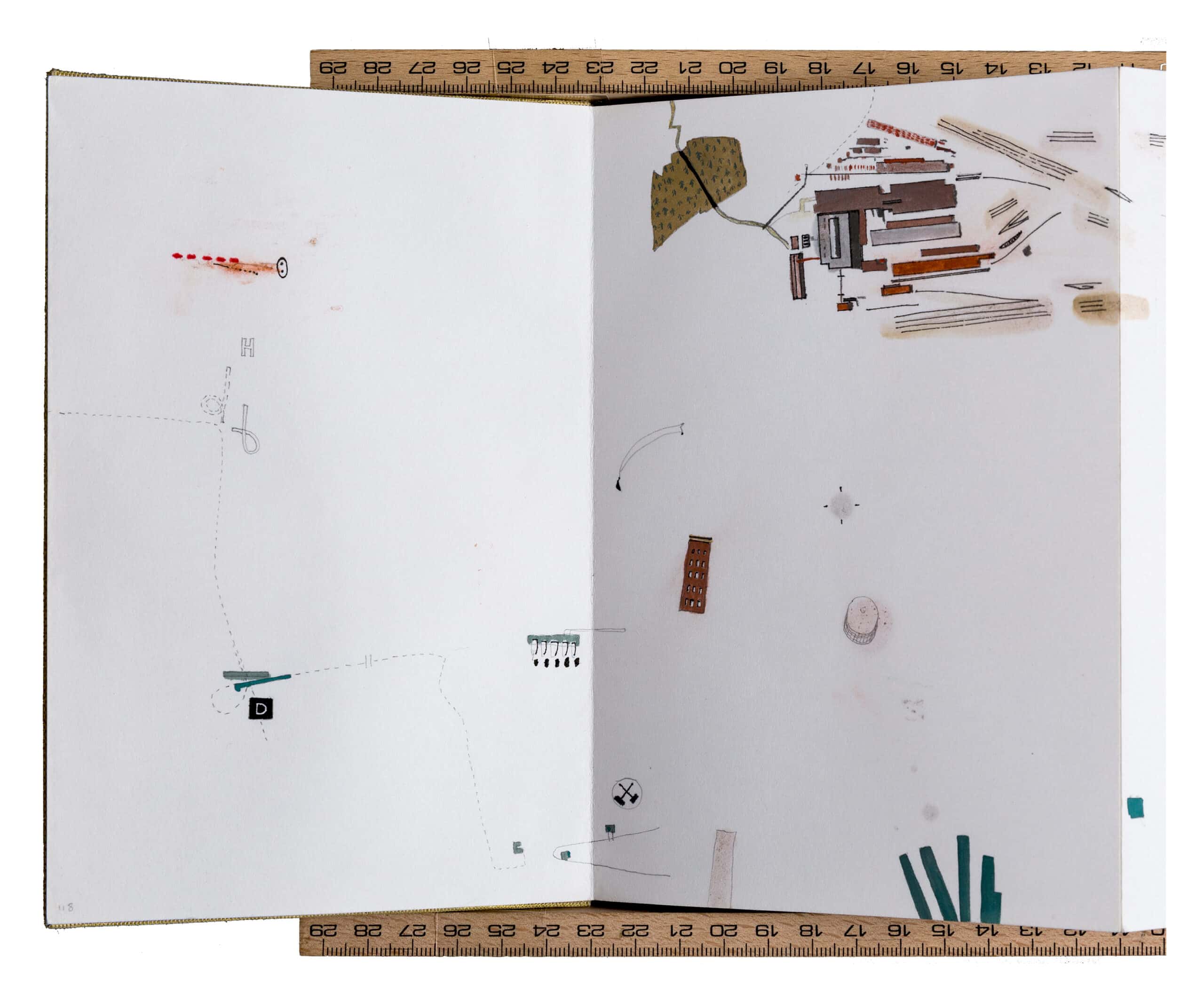

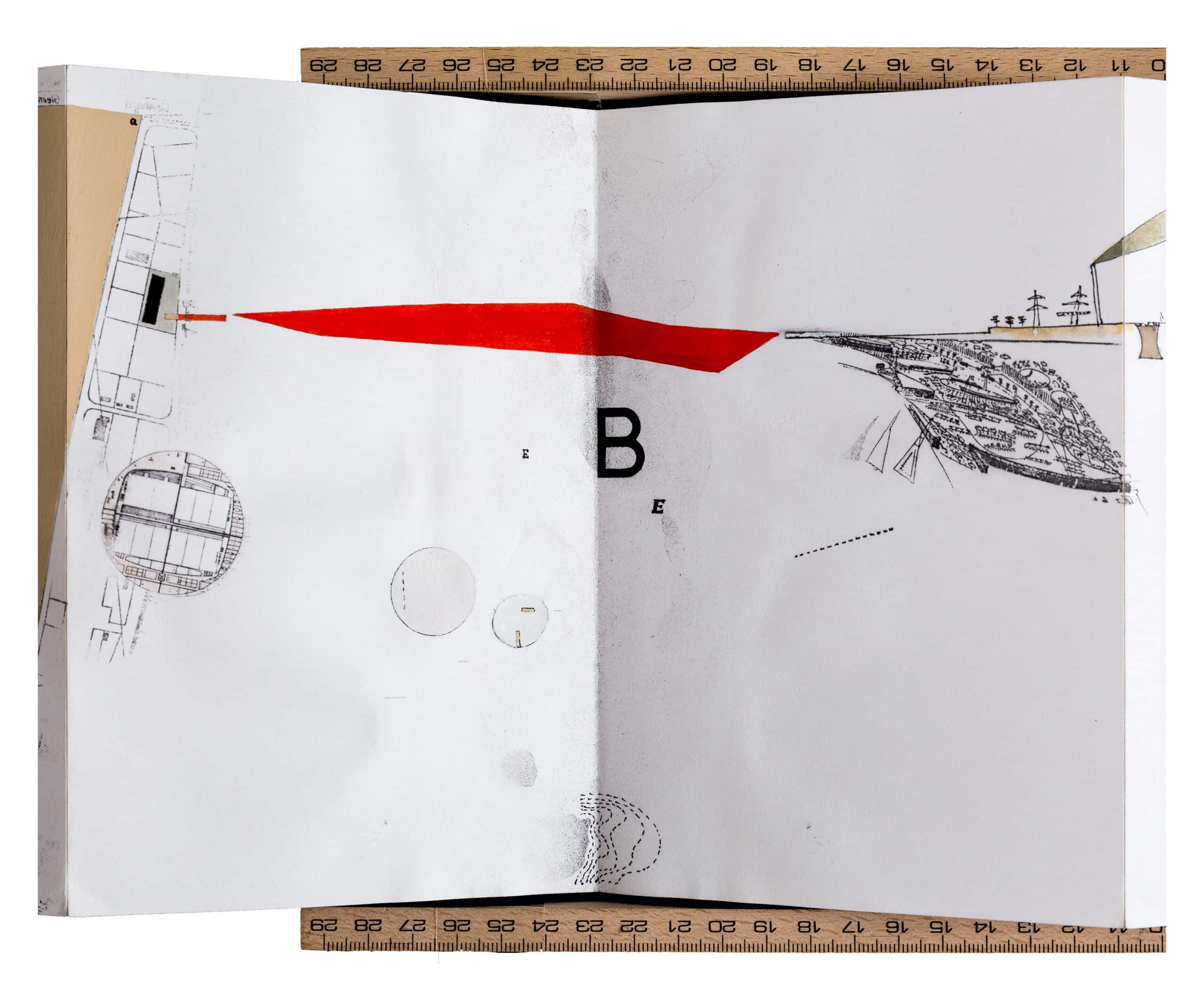

Peter Wilson, Eurolandschaft – A Derive

The train carriages trundle, we watch as one place sprawls into the next. We begin a game, trying to guess the point of transition – the edges between this place and the next, the soft borders implied by factories or gas stations or shopping centres – but it is impossible. We are left with a continuous impression of an intangible sprawl of in-betweeness.

Peter Wilson developed his urban concept of ‘Eurolandschaft’ through a series of train journeys, taking in the unfiltered and often un-noteworthy German landscape. His subsequent theory of urban sprawl is inseparable from his drawings of it.

Eurolandschaft can be read as one long complete scenographic map, or in sections, pages, fields. The viewer is positioned in the window seat, aware of the wider journey they are undertaking as they hurtle through small moments in plan, section and suddenly very close-up elevation. Inspired perhaps by Wilson’s visits to Japan and their history of narrative hand-scrolls, the user is control of the reading of the piece, unfolding the pages at their own pace. Rhythmic, fragmentary and sometimes falling-off-the-edge-of-the-page, the drawing snapshots a mode of viewing the landscape and thus engaging with it.

This map is selectively repositioning a personal journey and curates the viewer’s perception and inevitable relationship with this landscape through both its composition and unique format.

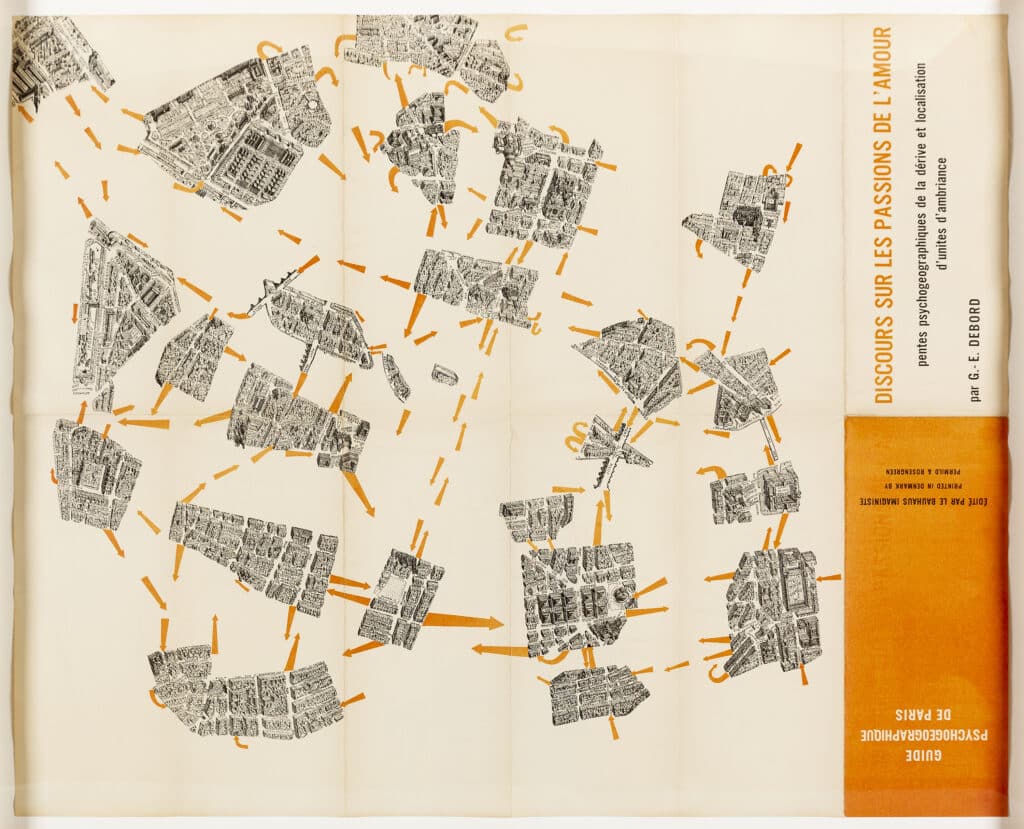

Guy Debord, Discours sur les Passions de l’Amour.

Borders that separate / Roads that connect

Put on your most comfortable shoes and leave by your front door. Look left, then right. Walk in the direction you feel like walking, then at the end when a choice has to be made, choose it. Turn, or maybe not. If it’s sunny you might cross the road, unless it’s too sunny in which case stay on this side. Now where? Keep going. Follow your nose, your footsteps, your dreams and desires but whatever you do try your best to escape from the noise of that horrible barking dog. You’ve found yourself outside your ex-lover’s house, perhaps that wasn’t such a good idea. Are they in? That’s not something you ought to know. Scurry on, look at the view from the top of the hill. Isn’t it vast?

Guy Debord’s psychogeographical map of Paris re-situates its neighbourhoods along their psychological contours. He reconnects places through love, atmosphere, memory and ambition, reformatting physical geographies through the wills of the people who tread them. The image of Paris as a whole is instead broken up to be read as a collective set of spaces that have their own relation to one another. Debord’s ‘derive’ is a walk of distraction, picking up the will of the city and following it through an intuitive drift. His city blocks are conscious.

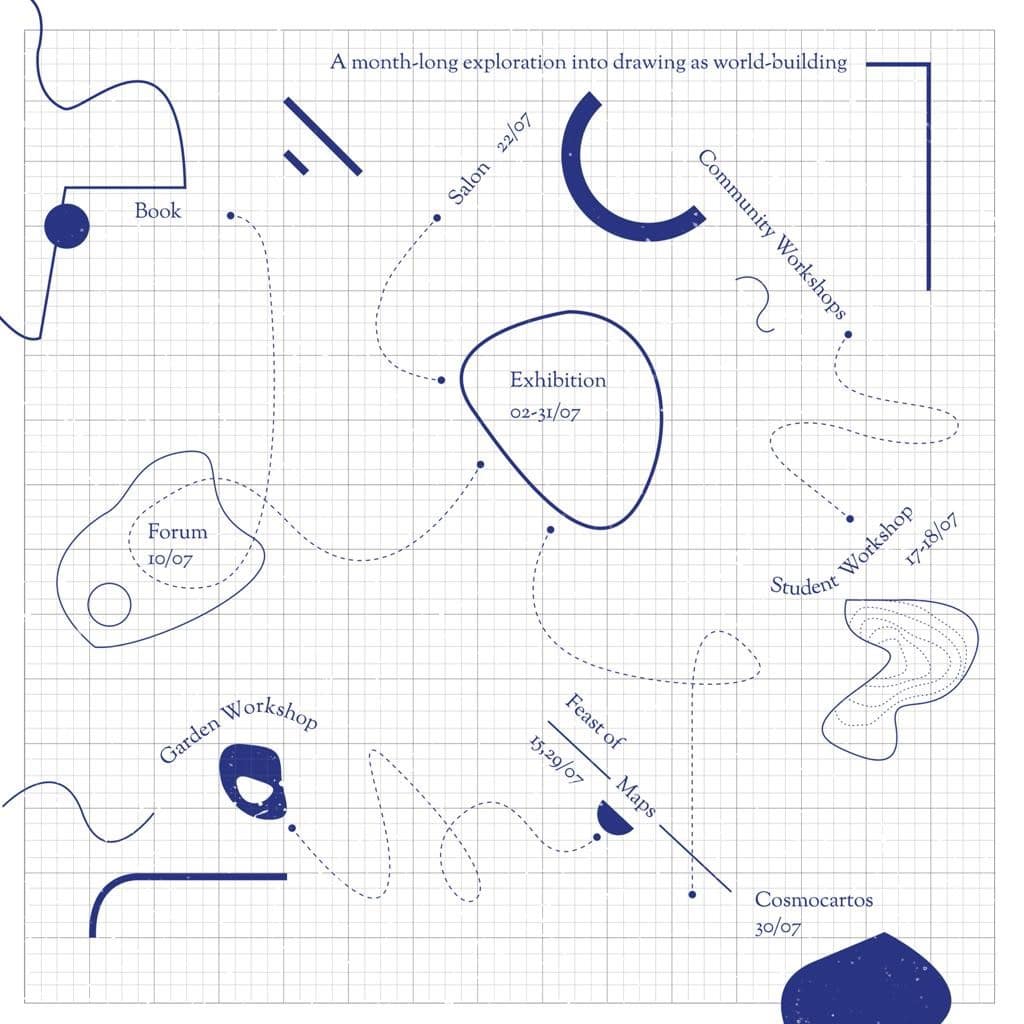

Cartographies of the Imagination is a month-long experimental drawing festival held in the RIBA award-winning OmVed Gardens in Highgate from 1st–31st July 2021. Alongside a series of events, exhibitions and workshops, we will be holding a Forum on Saturday 10th July alongside a Webinar, where we will discuss alternative approaches to mapping with a wide range of artists, architects and academics. The Forum will also be an opportunity to see the original drawings described above in the flesh, as they will be displayed and discussed in a round table between the curators and Drawing Matter’s Niall Hobhouse.