Imaginal Cloud Spaces

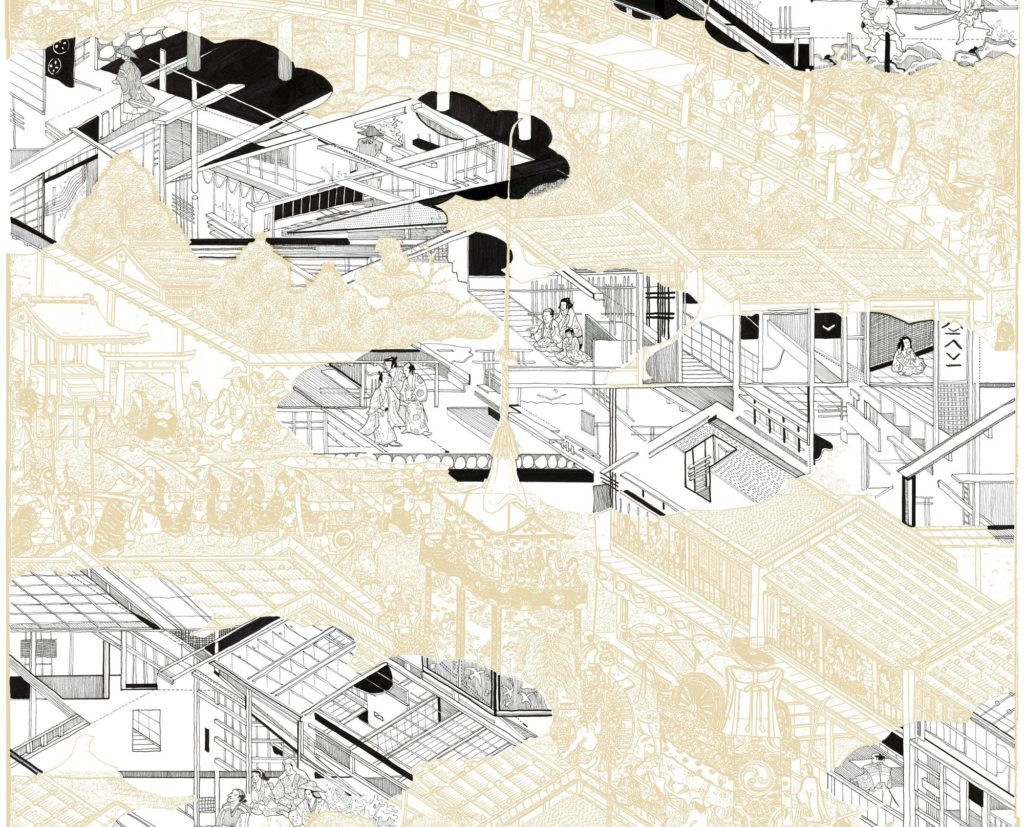

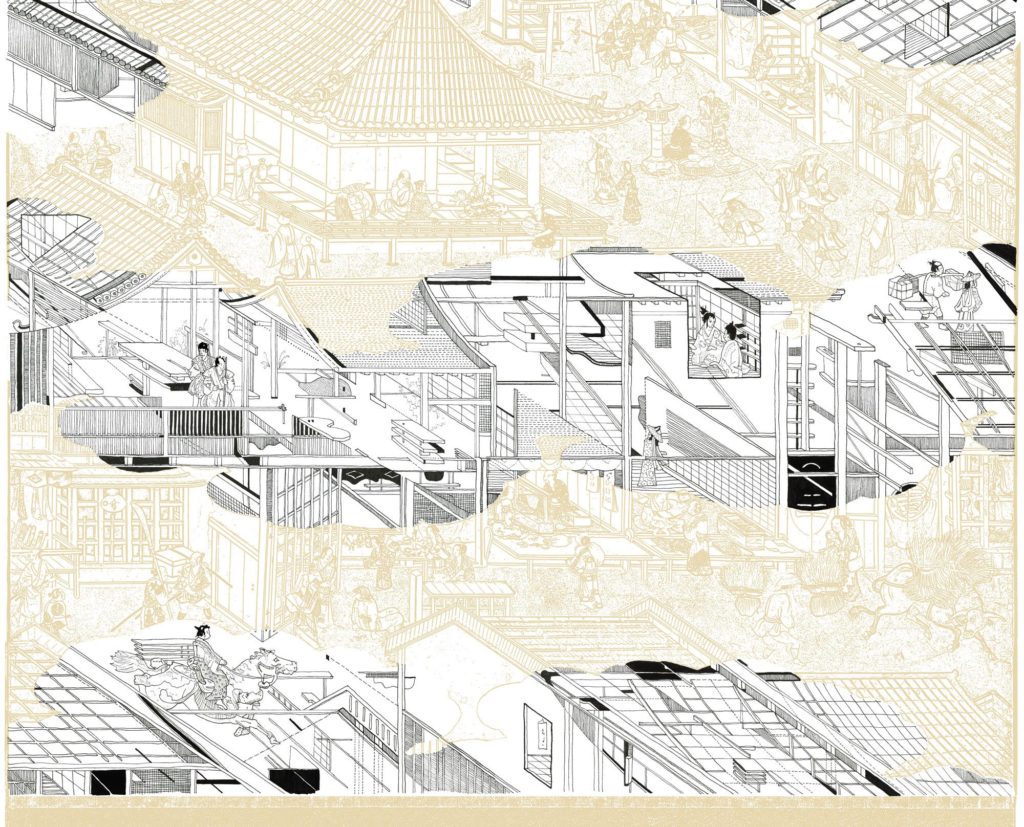

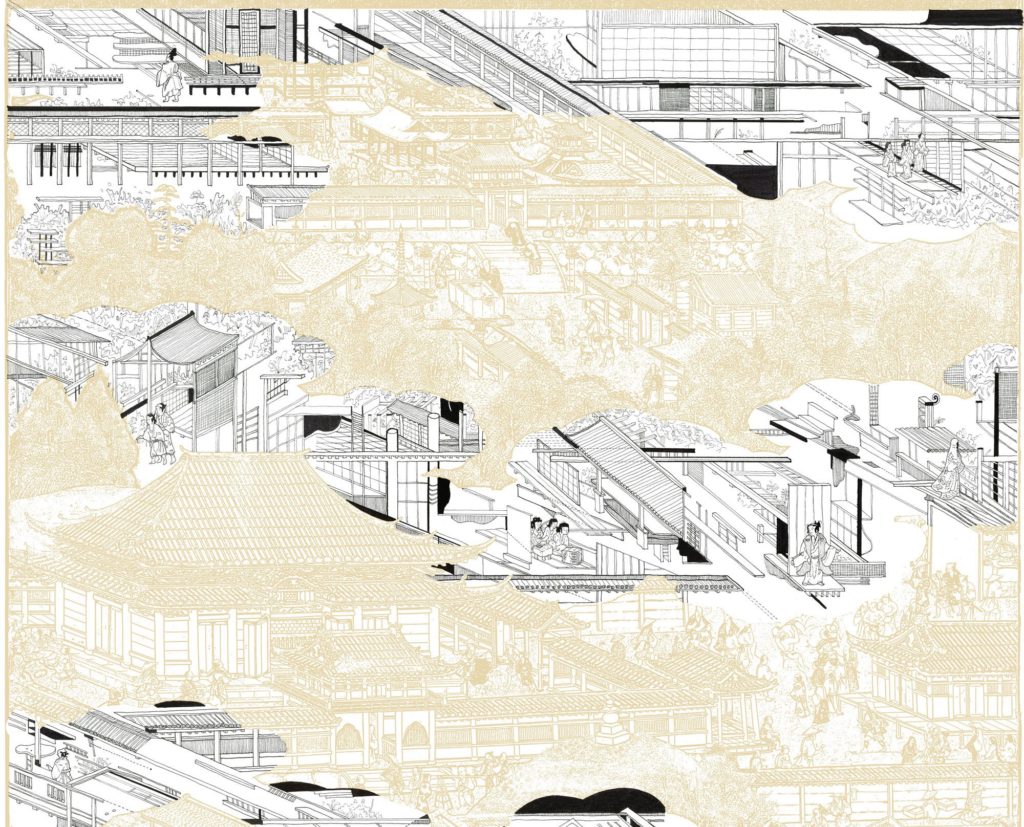

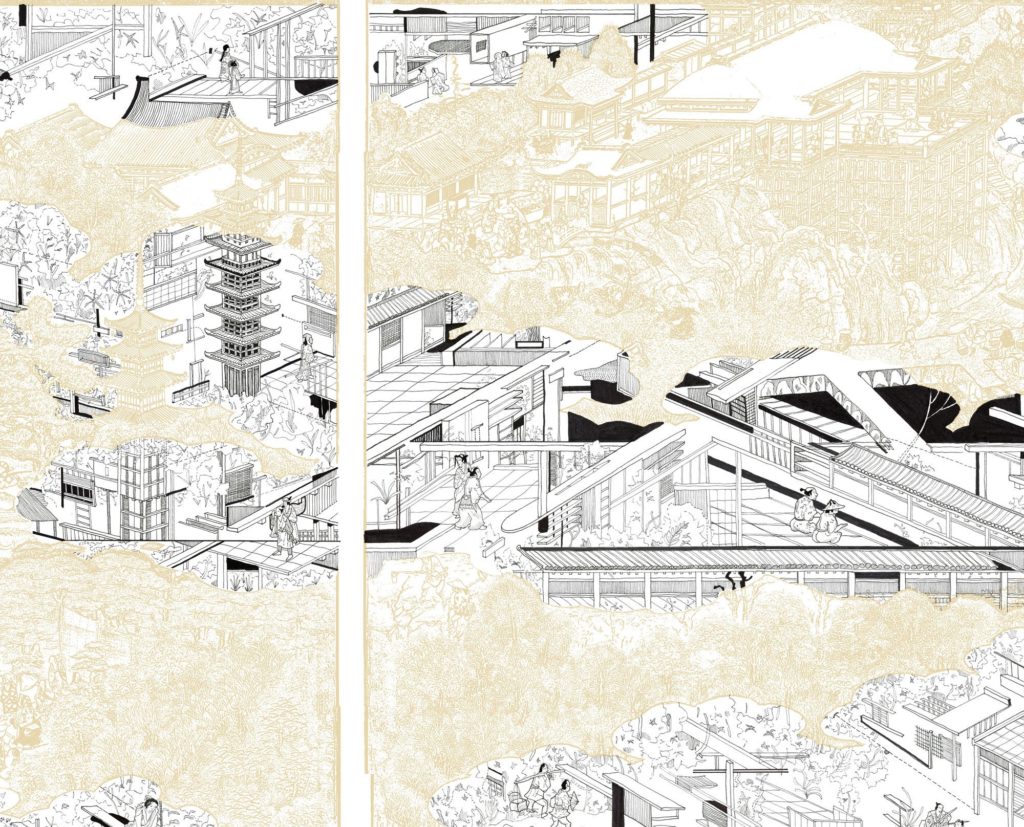

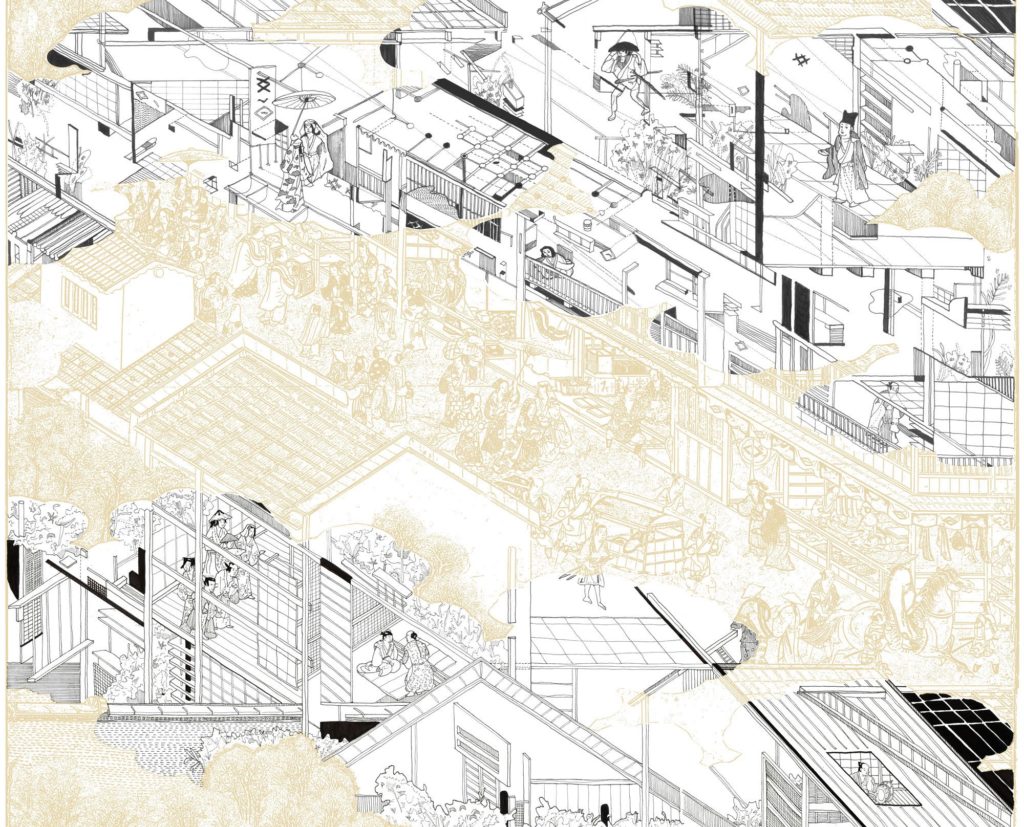

Many hours can be spent on what art historian Mary Berry calls ‘the sheer act of looking’ at the Japanese folding-screen paintings titled Rakuchu Rakugai zu (Scenes in and around Kyoto). [1] Across the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, such paintings captured a seemingly complete image of the capital city. Through the consistent use of aerial oblique projection, they depict a mythological vision of the city and its architecture. Famous landmarks are interspersed with the everyday goings-on of urban life within typical Machiya houses – we see people shopping, going to the theatre (Kabuki) or participating in street festivals. Though these paintings have been produced by different artists, most of whom remain unknown, and all have their own distinct styles, characteristics and focuses, they share a number of consistent properties. All Rakuchu Rakugai zu use a variation of oblique parallel projection (the perspective was a western invention) and depict a city partially concealed by gold clouds that sprawl across the folding screens.

Whilst these paintings identify real places in a real city, it is clear that they evoke the ‘idea’ of Kyoto rather than providing a factual, objective or accurate recording of its urban condition. Architectural author Hooman Koliji discusses the act of imagina [2] drawing as a means of harnessing ‘the world of ideas’ [3] and tapping into modes of consciousness and imagination. Parallel projection as a form of representation has long been understood to encompass ‘space as it is known in the mind’ [4] thanks to its inherently non-perspectival and out-of-body properties. In this sense the Rakuchu paintings do not represent any specific viewpoint of Kyoto but rather an amalgamation of how the artist imagines the physical, real city. These paintings exist within and provoke the imagination, with decisions about composition, angles of projection and scale informing ideas about place in our mind as our gaze wanders through the spaces of the painting. Koliji describes this as the ‘in-between’, [5] the gap between real and imagined worlds that drawing mediates.

Ordinarily, information about the compositional decisions and intentions of the artists of these historic paintings would be discerned through textual evidence, notes, descriptions or diaries, which might explain the significance of the arrangement of the buildings and sites of the urban make-up of Kyoto. Sketches, preparatory drawings or half-finished studies would give us further insight into the developmental process of building the image of the city. But this type of information is not available today: it hasn’t survived centuries of fire or destruction, or perhaps it never existed in the first place. This means that all we have to gain insight into the minds of the artists and the process of world-building that the paintings represent are the Rakuchu screens themselves.

Is it enough to rely on the sheer act of looking to unpack, understand or inhabit the world that is implied by these paintings? For many, getting lost in the seemingly endless detail and beauty of the paintings can be a form of escapism – displacing yourself as your eyes traverse the surface of the screens. But to understand the artists’ practice of composition on an intimate scale, looking forms only the start of a process that is better explored through drawing. Ray Lucas describes this process in Drawing Parallels (2019), where he interrogates the work of five architects in axonometry, as ‘understanding the drawings as scores to be re-enacted … it is only by performing the drawing that aspects of it are revealed’. [6] This assertion – that drawing itself can be used to tap into the psyche of the drawing or artist inhabiting the in-between and in turn create new imaginal drawings – begins to pose interesting questions about the tools we have to analyse images and drawings.

Scenes of Another Kyoto is a drawing study of the Seiganji screens. These screens are a seventeenth-century version of Rakuchu Rakugai zu, and they take their name from their enlarged focus on the Seiganji temple, which in reality is rather modest. This drawing does not overwrite, delete or edit the spaces of Rakuchu Rakugai zu, but instead uncovers new space within the painting previously obscured by the gold clouds. The clouds perform two visual operations – they allow the gaze to leap from one part of the city to another, compressing the space between famous sites, and they control the balance and composition of the painting by simultaneously framing and concealing the urban sprawl. These strategies are enhanced by the use of gold leaf and embossed gofun (crushed shells) that lend these essentially blank parts of the painting a sense of gravitas and dream-like splendour. By drawing within these spaces, inhabiting the surface of the clouds, I disrupt the painting’s logic and expose its framework, continuing projection lines from the neighbouring spaces into the cloud itself. The realm of my drawing is anchored to the painting as I continue and ‘complete’ the picture of the city, yet the drawing also forms a space of speculation, as the clouds are not intended to represent a tangible or coherent territory.

My desire to inhabit the imaginal qualities of the spaces defined by the original artists came from a fascination with the painting and its compositional arrangement. In understanding how angles of projection vary, conflict or overlap between parts of the city and how the use of gold cloud interrupts and re-navigates our perception of the city as a whole, I tap into ‘score’ of the painting, as Lucas describes. Rather than simply re-performing this score, my process re-interprets its underlying framework and develops a drawing language that is distinctly speculative while drawing from and belonging to the architecture of the painting. Studying the painting in this way – by drawing projection lines, completing buildings and inhabiting the space of the cloud – allows a form of embodied engagement that the act of looking on its own cannot provide. In doing so, I explore ways in which the imaginal properties of drawing, used by the artists as a design tool in curating the image of the city, can inform and trigger new drawing practices that explore the ‘in-between’.

Notes

- Mary Elizabeth Berry, The Culture of Civil War in Kyoto (University of California Press, 1997), p 298.

- Hooman Koliji, In-Between: Architectural Drawing and Imaginative Knowledge in Islamic and Western Traditions (Routledge, 2016), xxiii.

- Ibid.

- Yves-Alain Bois, ‘Metamorphosis of Axonometry’, DAIDALOS: Berlin Architectural Journal 1 (1981), p 49.

- Hooman Koliji, In-Between: Architectural Drawing and Imaginative Knowledge in Islamic and Western Traditions (Routledge, 2016), xxiii.

- Ray Lucas, Drawing Parallels: Knowledge Production in Axonometric, Isometric and Oblique Drawings (Routledge, 2019), p 2.