Pan Scroll Zoom 9: The Screen ClassRooms

This is the ninth in a series of texts edited by Fabrizio Gallanti on the challenges in the new world of online architectural teaching and, particularly, on the changing role of drawings in presentations and reviews. In this episode Anuj Daga, Assistant Professor at the School of Environment & Architecture, Mumbai, explores the changes to teacher-student relationships in virtual teaching environments.

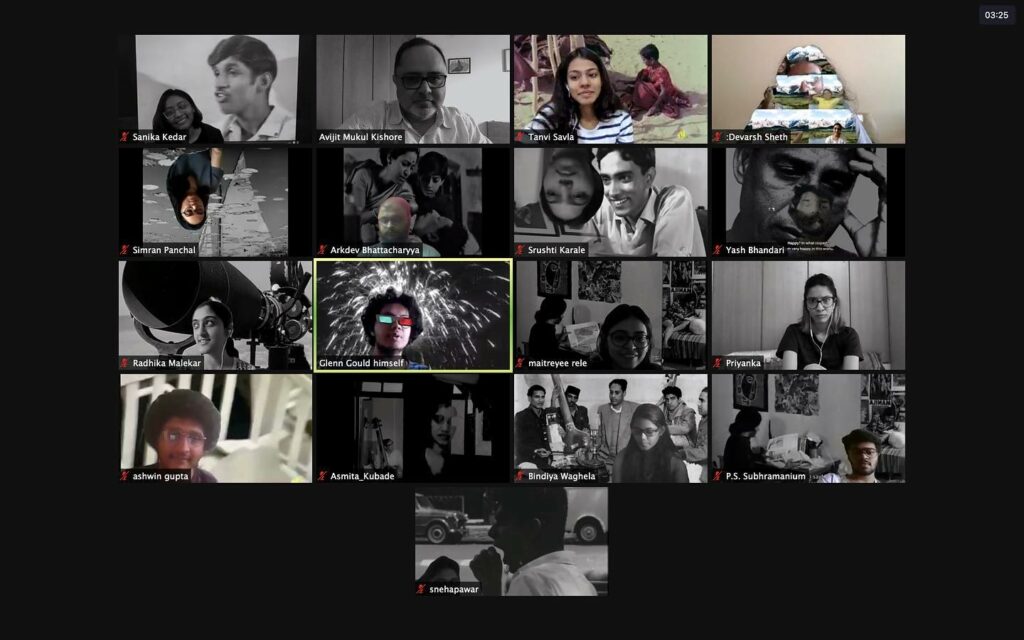

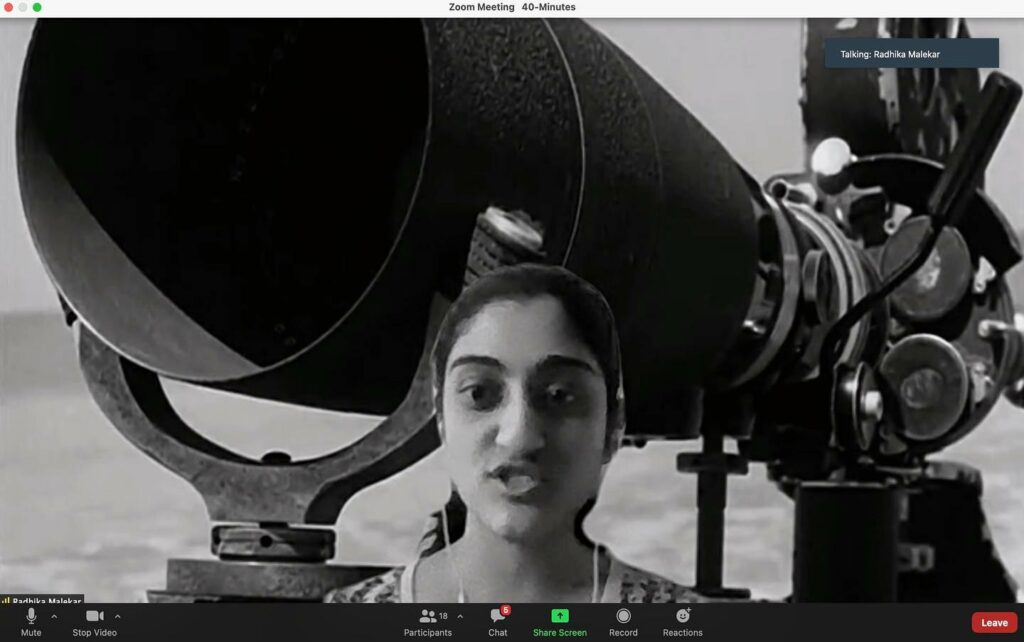

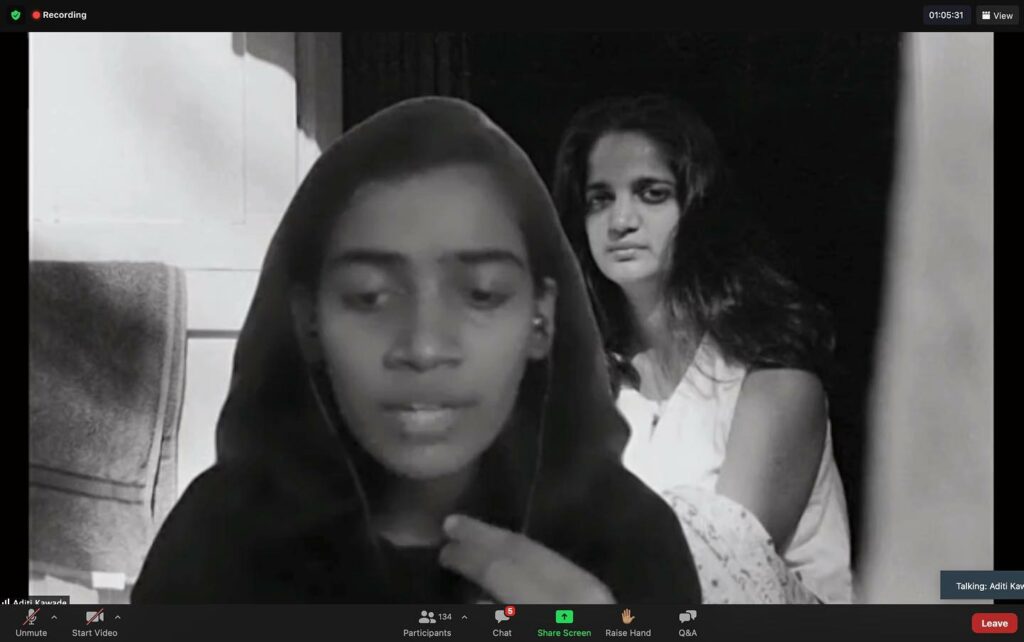

For the final presentation, the students made a random selection of text from the curated films they had seen. They read this text sequentially while posed against the frame grabs or live video backgrounds from these films, that generated inadvertent meanings ranging from the sincere to the ironic, the absurd to the comic. The backgrounds, filters and modes of superimposition were all selected by the students. [1] (Image and caption courtesy: Avijit Mukul Kishore.)

Classrooms are sites of simultaneous arrival and escape. The pathways of arriving at any understanding of a considered subject are traditionally held within the classroom’s phenomenal sociality: one that is a complex nexus between the body of the performing teacher and the escaping gaze of the listening student. Within the ritual of the screen classrooms during the COVID pandemic, this agency of the speaker, otherwise asserted by their bodily presence, voice, gaze and actions has been greatly fragmented. The socially constituted figure of the teacher experiences a double suspension within the screen classroom. Not only has the body become virtual, but also it is no longer able to establish control through its performance to the bodies in front of it. Such a scenario allows new trapdoors and alleys of escapement (or even association) through a range of subversions and inversions of force vectors.

No longer may the teachers demand the attentiveness, presence and alertness that traditionally has been expected of the bodies of the students. Students can now lounge, stroll, wander, eat, sleep, chat, snoop, disappear, multitask or even un-participate while still being in the discussion. What would the physical form of the classroom be if these conditions were to be accommodated within the physical idea of the classroom? The image and the sound, once fixed by the body of the teacher within the physical classroom, now seem to have disintegrated into headphones and laptops – and even mobile screens. With the portability of these devices, they seem to have further fragmented what constituted the body of knowledge itself. Such reworkings help us revisit the socially constituted body of the teacher and the student. They beg us to reconsider, what it means to transmit or absorb knowledge on the peripheries of such socially disciplined bodies?

At once, the screen has imploded into all its metaphors – of being the mirror, window, shield or even a video game. [2] The interface of video chat platforms presents to us, more often than not, a window-grid of faces and names across whom our eyes roll. One of these is us – a reflected self whom we check periodically out of the self-concern for (on-screen) vanity. This literal opportunity of seeing/evaluating the self as the performing body was not available during the delivery of the lecture within the physical classroom. As a mirror, the screen often makes the teacher more conscious of their own body-acts. This screen mirror has increased the frequency of instances we tidy our hair, readjust our postures or even elevate the camera-embedded laptop device on a set of borrowed books and improvised props, towards an appropriate self-construction.

At other times in the screen classroom, we gaze into the world of our listeners, trying to interrogate and inhabit their varied spaces. New domesticities, socialities, soundscapes and backgrounds recontextualise the subjects we speak to. Taking soft mental notes of the textures of the lives that our students inhabit, we recalibrate our tones of engagement. In a place like India, where students mostly share space with their immediate families, these domesticities are diverse and telling – producing unique empathies and proximities within otherwise transactional student-teacher relationships. The wall colours, artefacts, shades and patterns of curtains, floral bed sheets, pillow backings, varyingly lit interiors, mosaic stone wall claddings, steel cupboards, decorative false ceilings bring material histories that speak of a distinct aesthetics of inhabitation. The screen space offers a visual imprint of such heterogeneity literally backgrounding students with their respective cultural contexts. In contrast, the spatiality of the physical classroom is fairly neutralising, assuming and facilitating a homogeneous narrative, although one that is necessarily absorbed in heterogeneous ways. It is here that we become aware of the white-cubing context of the institution of the classroom itself.

At times, distant environments meld into each other through pure digitonics, blending the adjacent screen-windows into one by mere coincidence of colours, sleight of framing or deception of camera perspective. These are times when disparate geographies collapse virtually into each other, reconstituting into an amalgamated heterotopic classroom. Initially the black windows of muted and screened participants would frustrate us, forcing us into a blindness of sorts. They necessarily make us anxious about being heard, understood – sometimes even pushing us to interrogate the relevance of our own presence. However, the decision to screen oneself may be multifarious, informed by low internet bandwidth, hesitation to make one’s personal space(s) visible, being in inappropriate settings, untimely presences, safeguarding shared privacies, allowing domestic simultaneities and many such other situations that we remain insulated from in the otherwise neutralised classroom.

Within the screen classrooms, the notion of presence and absence is totally mixed up, but could also be liberating. In a recent review, an invited critic cited Schrodinger’s paradox as she continued to smoke a cigarette while attentively offering feedback on student work: ‘I am there and still not there, so I can technically smoke within the classroom!’ she said. On the other hand, the classroom is merely a function of managing windows – you could be browsing another window on your screen while still doppelganging your gaze for another. Nobody can assure or challenge presence, even when the gaze of the other speaker is available to us. One could be physically invisible yet attend the class, or one could make oneself all visible and still be engaged in another world, through another screen-window or even another physicality. Further, the students’ attendance is reduced to the momentary digital recording of presence – which may be interrupted by fluctuations in the internet stream. The classroom is pixelated into windows with no real eye contacts.

And yet, in spite of the virtual folding in of the world, some desire the warmth of another’s flesh, or long for the peripheral silence of another body, and to charge themselves with the impulsiveness of an external unfiltered gaze. Friends separated across time zones and continents are now equally distant. Although the challenges in different geographies are quite varied and must be compared with care, all distances have virtually equalised. In such situations, it is crucial to understand how the architectural ‘studio’ reconstitutes itself. The studio culture, in addition to the theoretical seminars, is crucial to architectural pedagogy. Most of us who have experienced one, will agree that design learning happens in peer discussion, eavesdropping into in-process models and drawings towards anticipating failures, mistakes and potentials, peeking into the books that one did not choose to borrow from the library but found on a friend’s desk, or even casual discussions that digress into serious crit sessions over matters of design. Intersections with physical environments while traveling to the studio shape our design orientations as much as conversations within the classroom. The studio is thus an expanded environment that cannot be contained within the bubble of the home, or the confines of the screen. The screen classroom is an implosion.

All in all, the screen classroom has exposed us to what may be understood as the diegetics of pedagogy – one that compels teachers to engage with the interior world of their students in order to (re)formulate the narrative scope of education. How could these renewed geographies of assimilation reconfigure environments of teaching and learning? How creatively can pedagogical processes curate these passages of arrival and escape? More recently, video chatting interfaces allow customisable backgrounds to place oneself in virtual locations. Such a feature helps people to mask their lived realities, while simultaneously revealing individual aspirations, desires, moods; in short, the mental-scapes they (might want to) inhabit. One of the film appreciation course conductors invited at our school [3] harnessed these very energies into his exercise to produce a live Zoom performance using archival text, images and videos from the films that were discussed over his four-day workshop. Over the presentation, students brought their bodies, backgrounds and voices together in order to demonstrate their learning about framing, montage, scripting, image and meaning-making over the virtual interface. It is here that the students allowed us an entry into their dreamscapes while asking us to escape into our own.

Notes

- Avijit Mukul Kishore, Winter Elective Presentation by the Students of School of Environment and Architecture. Accessed February 27, 2021. https://vimeo.com/512374328/0a815a257b.

- I borrow these conceptual formulations from the reading of Casetti, Francesco’s ‘What Is a Screen Now-a-Days?’ in Chris Berry, Janet Harbord, and Rachel Moore, eds., Public Space, Media Space (Palgrave MacMillan, 2013).

- Mumbai-based film maker Avijit Mukul Kishore was invited to conduct an online film appreciation workshop at the School of Environment & Architecture (SEA), Mumbai, India, during 2–6 February 2021.

– Patrick Lynch