Reading Dirty Old River

The act of looking is complex. It varies depending on the observer, the medium, and what is being observed. In Dirty Old River, the observer, Tom Emerson, is looking at the world through the eyes of photographers, writers, and artists among a larger set of characters. The observed range of artefacts is images, drawings, and photographs. Compiled over a period spanning almost three decades from 1998 to 2024, the essays constitute a prism through which these variables are examined.

Writing as a tool, unlike drawing, removes the added pressure of aesthetics. Through sensory observation of the eye, the hand records what is seen and felt. This tactility begins with the physical matter of the book. A perfect bound sewn arrangement enveloped in a smooth cover; it lies flat when open and retains its plasticity when closed. Practical enough to stay open for extended reading but pliable enough to carry around and maintain durability. Its cover bears the colour suggested in the title: a dirty, muddy, reddish-brown.

The essays within approximate embodied meditations on the art of looking.

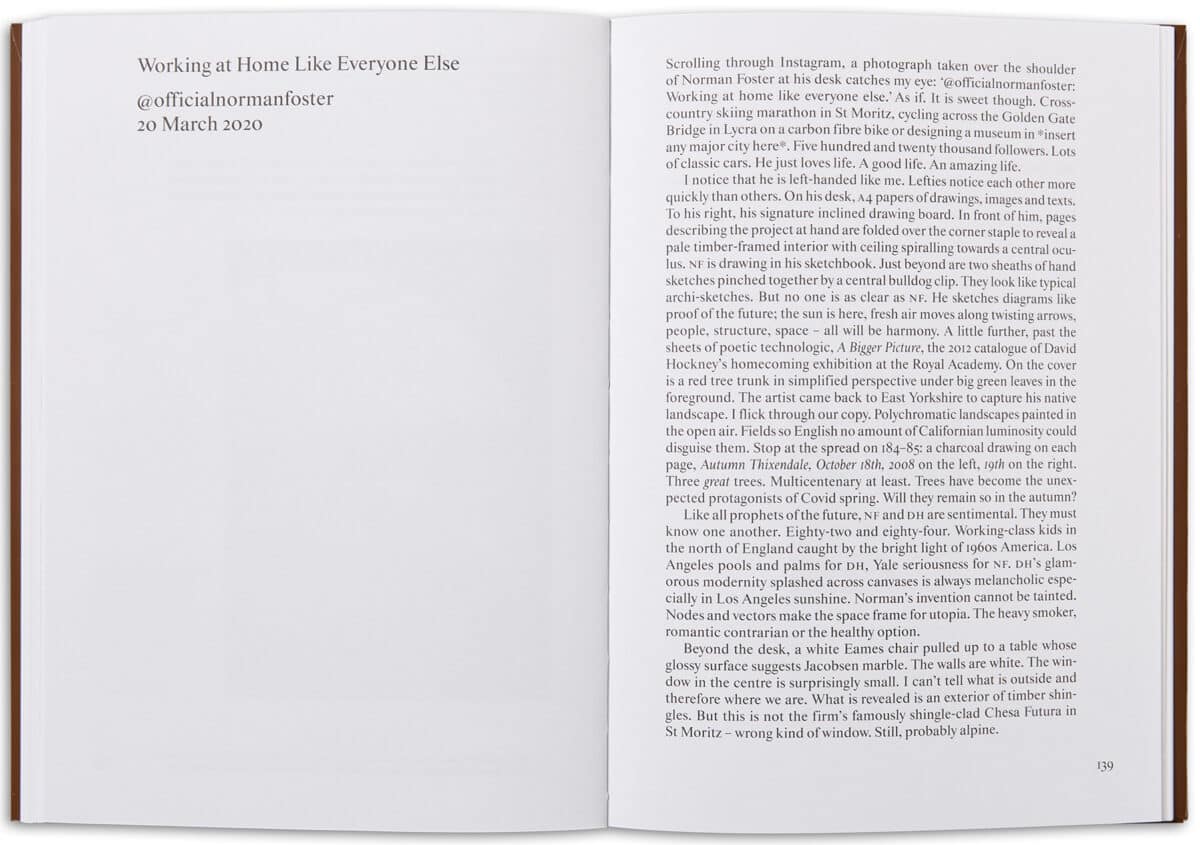

‘Working at Home Like Everyone Else’ describes an Instagram post of Norman Foster, which shows him working at his desk. What begins as a series of prosaic observations—sketchbooks, drawing board, models—becomes an acute attempt at positioning time and space. The value of pursuing a process of looking is in being able to piece together a wider narrative from a snapshot in time. There is a forensic quality to the observing eye as it looks for clues to extend the timeline backwards and forwards beyond the image; to locate geography hinted at by external shingles; to make attempts at continuing the narrative beyond the picture frame.

The analytical eye fills what the frame omits.

Jürgen Teller, rendered through Emerson, teaches us the way a photographer sees, and it is different yet again. Teller’s images render the world through his photographic lens, a mechanical eye. The ability of his human eye to spot the decisive moment and the mechanical eye of his camera to follow suit promptly speaks to another type of hand-eye coordination. The image passes through the eye, is internalised and re-released back into the world in a creative act to re-present what is already there anew. Teller’s images are startling, surreal, and hard to conceive as a source. Yet they are a product of another kind of looking that makes visible an already existing reality.

These situated environmental photographs turn the dial up on the everyday condition in a way that feels heightened and almost surreal.

For all its forensic quality, the eye can be tricked. Looking at, or through, the work of others outside the discipline—such as artist Monika Sosnowska—leads to another type of observation. ‘This is not a Pipe’ appears to be a play of appearance versus reality, where the eye is unable to differentiate between the perceived appearance of an object and its physical reality. The artist’s scale model—the miniatures—uses paper card cut in a way that imitates steel. At a 1:1 scale, the life-size sculpture uses steel to represent the folds of the card. In a scenario where one cannot touch for temperature or tap to gauge the density of materials, such inversion prompts active looking and scrutiny to unpack ideas of materiality and gestural impression.

The artist understands something of material directness that the architect could learn from.

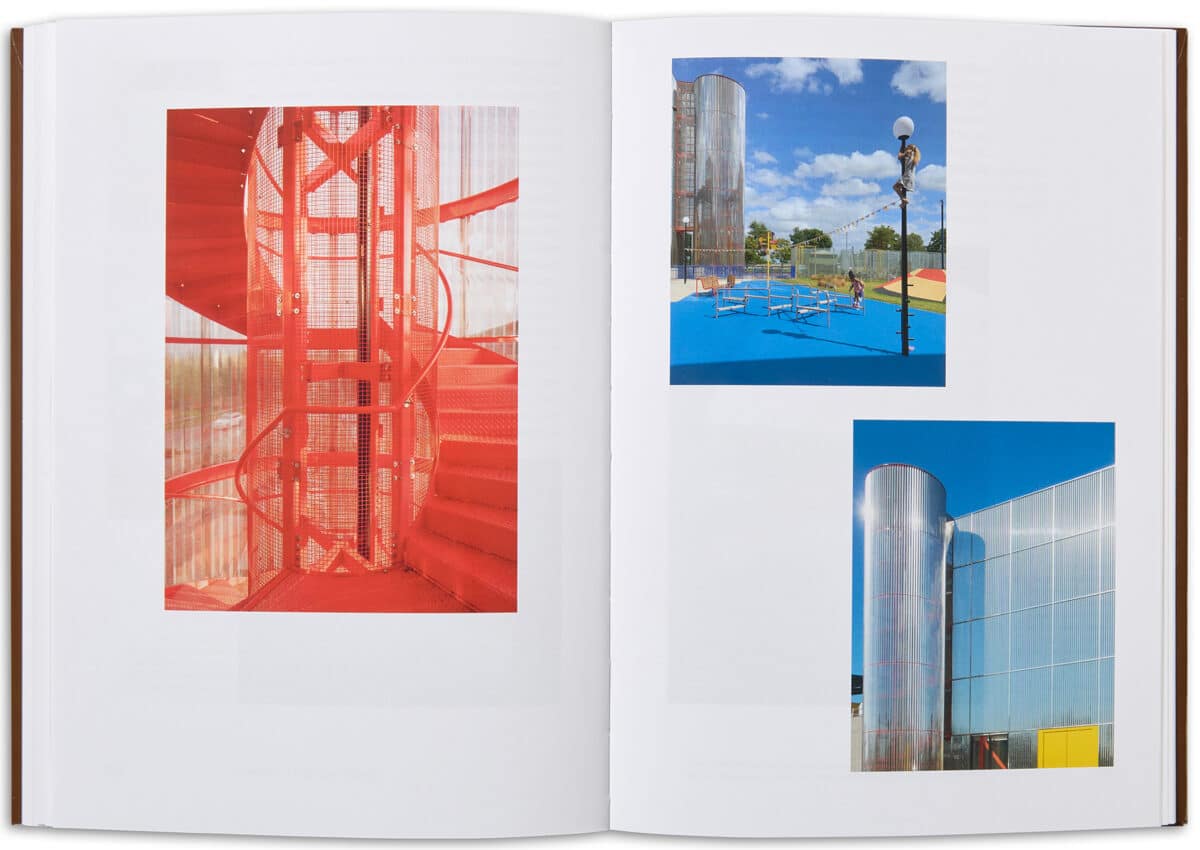

The nature of the medium also has an influence. ‘Cutting Corners’ examines an image as a gateway to another culture. It uses an evocative image of two men digging as foreshadowing for an architecture that reinforces the image of the ground beneath it. This calls forward the imaginary potential of a stimulated eye, one loaded with imagery, that dares to dream, to revel in conjecture and to imagine new possibilities. The eye here becomes a tool for forward projection as much as it is a tool of recall or memory. Like the image which inspires it, ‘Cutting Corners’ carries on conjuring many more vivid images of people, place, and geography in perfect unity. The image of children occupying cut corners as a small gesture of generosity opposite football fields becomes one fixed in the mind’s eye.

As the subject of what is being looked at changes, so too does the material gleaned.

‘Tolerance’ explores looking at architectural drawings and how these carry the variation and complexity of cultures. A comparison between Frank Gehry and Peter Zumthor’s drawings predicated on the use of a shared material reveals not only site-specific, geographical differences in the treatment of materials, but also in the temperaments of the architects. Zumthor’s measured drawings of Saint Benedict Chapel in Switzerland are contrasted with the immediacy and intuitiveness of Gehry’s drawings for projects in LA. Both are products of the individual psyche as it interfaces with prevailing modes of construction. In this way, information about craft cultures can be uncovered. The drawing as an artefact is a record of this specificity of place.

Looking from within differs from all other modes of seeing. There is a different experience when one is accustomed to a place. ‘Dirty Old River’, the essay which lends its title to the collection, begins with Emerson telling us what London is not good at—public space—accompanied by an ‘unruly temperament that has never accepted grand urban gestures or masterplans’. So familiar he is with its vices and virtues that he feels comfortable in sharing its shortcomings. Contrary to essays where the act of looking at an artefact offers a gateway to another culture, this essay relays the insider perspective of a place. Here, the eye is a sort of passenger taking a back seat as the feet retrace familiar ground. Learning to see what you are accustomed to seeing anew, getting past the ‘everyday’ offers a different type of beauty, not one of discovering another culture but rediscovering your own.

Emerson’s eye registers continuities, recognises change. It is a silent witness to a changing environment. There is an impartial quality to this detached observation that reads and records without opinion or judgment. There is value in learning to decode the ‘opacity of the quotidian’ as Georges Perec would put it, in looking at one’s immediate and familiar environment. Making recordings of observation through writing is one of the ways we can preserve place, space and memory against constant erosion, be it natural or man-made. Perec’s observations are true. Without the ability to observe and record, we risk silent erasure, disappearance, even loss.

*

Marwa el Mubark is an Architect and co-founder of Saqqra, an architecture practice based in London. She is also a design tutor at Kingston School of Art.

– André Patrão