From Diderot to Tokyo: Mechanical, Subjective and Digital Time

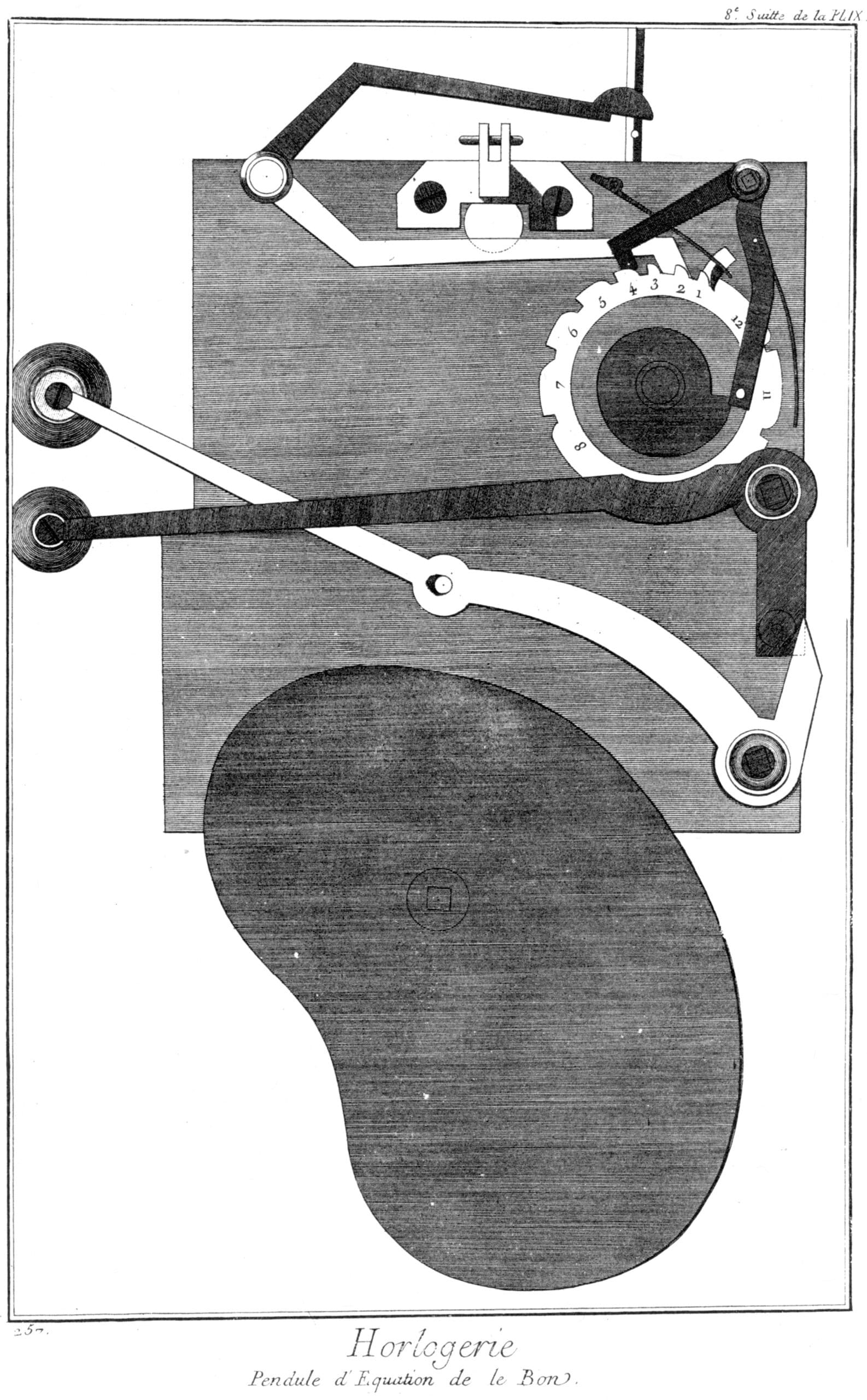

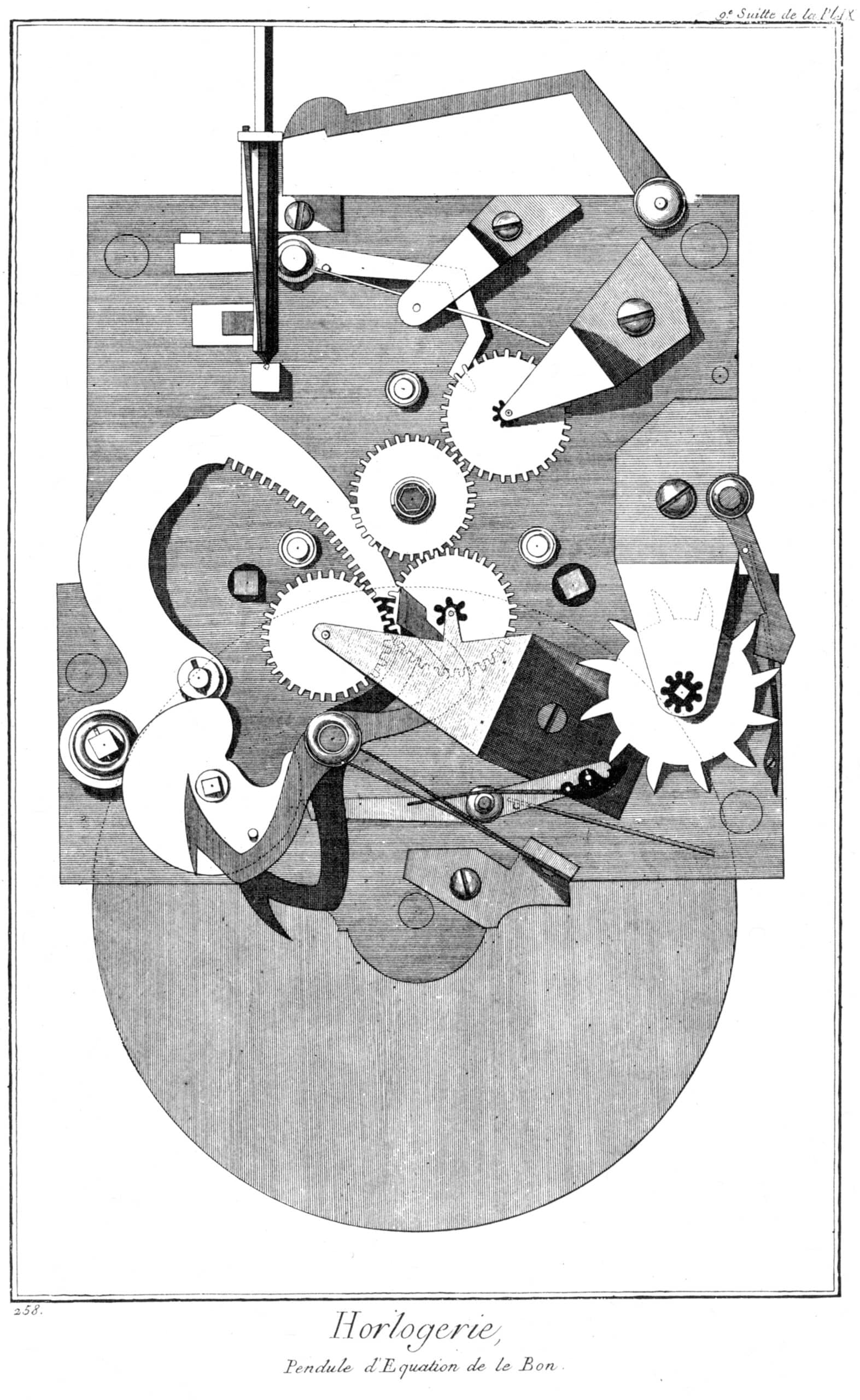

The absolute precision and technical specificity of Diderot’s encyclopaedia plates, particularly those devoted to Horlogerie, mark a critical moment in the transition from speculative to operative science, from the pre-industrial to a modernist ontology of technical instrumentalisation. Here on these pages, artisan craft is ransomed to the immanent logic of mass production. Here time itself is captured and quantified in the precise interlocking wheels and cogs of clock gearings.

In the plates a second transfer is also enacted, that of recomposing the pre-eminent object status of an artefact. Its dimensions and complex operations are codified, rendered coherent as image, as a rational and relational two-dimensional synopses. Already in the oft-commented separation of text and image, Diderot implies an autonomous iconography of the represented object which today, with the eclipse of the original didactic purpose, gives the plates a compelling poetic depth, ‘an infinite vibration of meaning,’ as Barthes wrote.

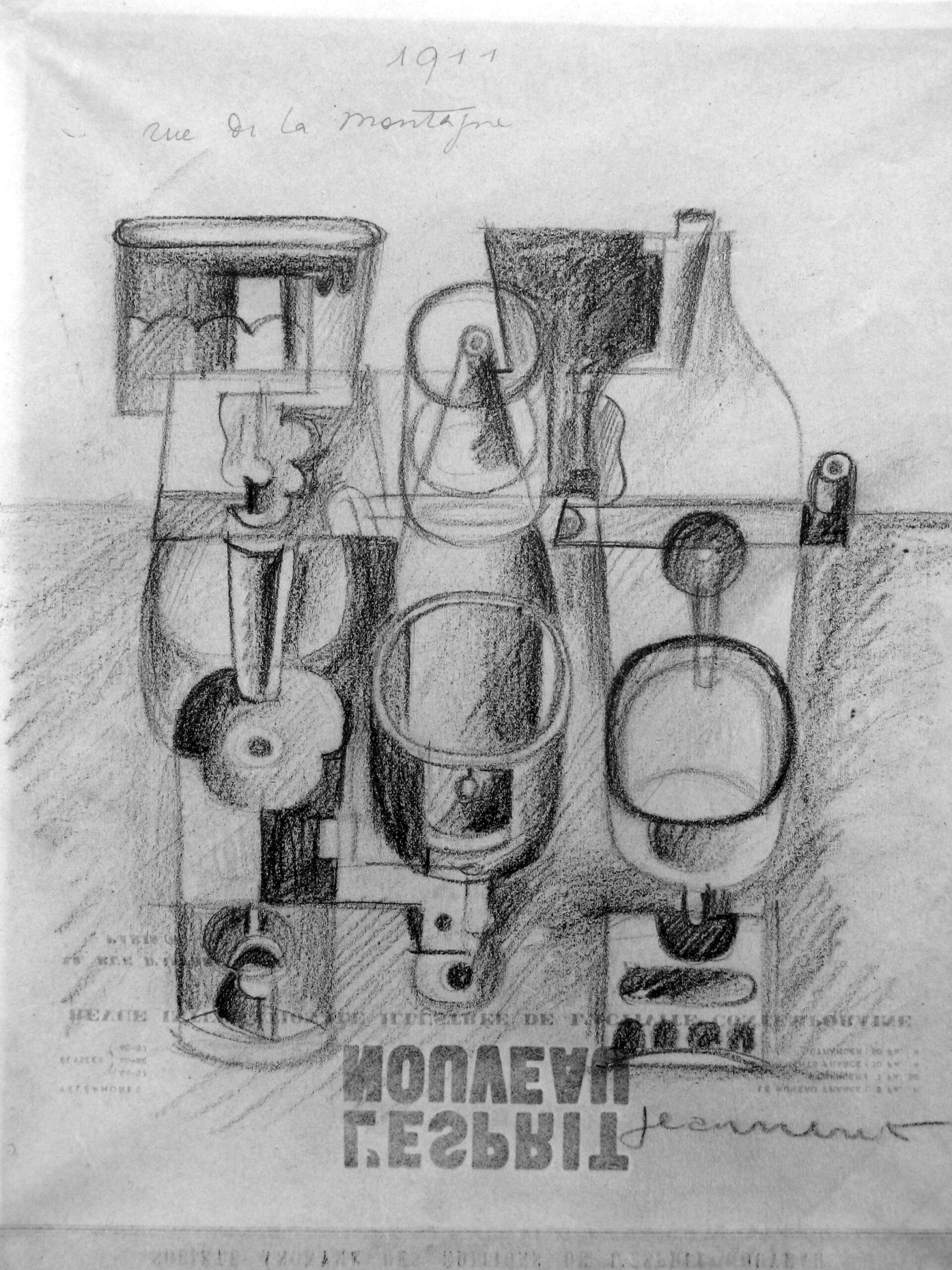

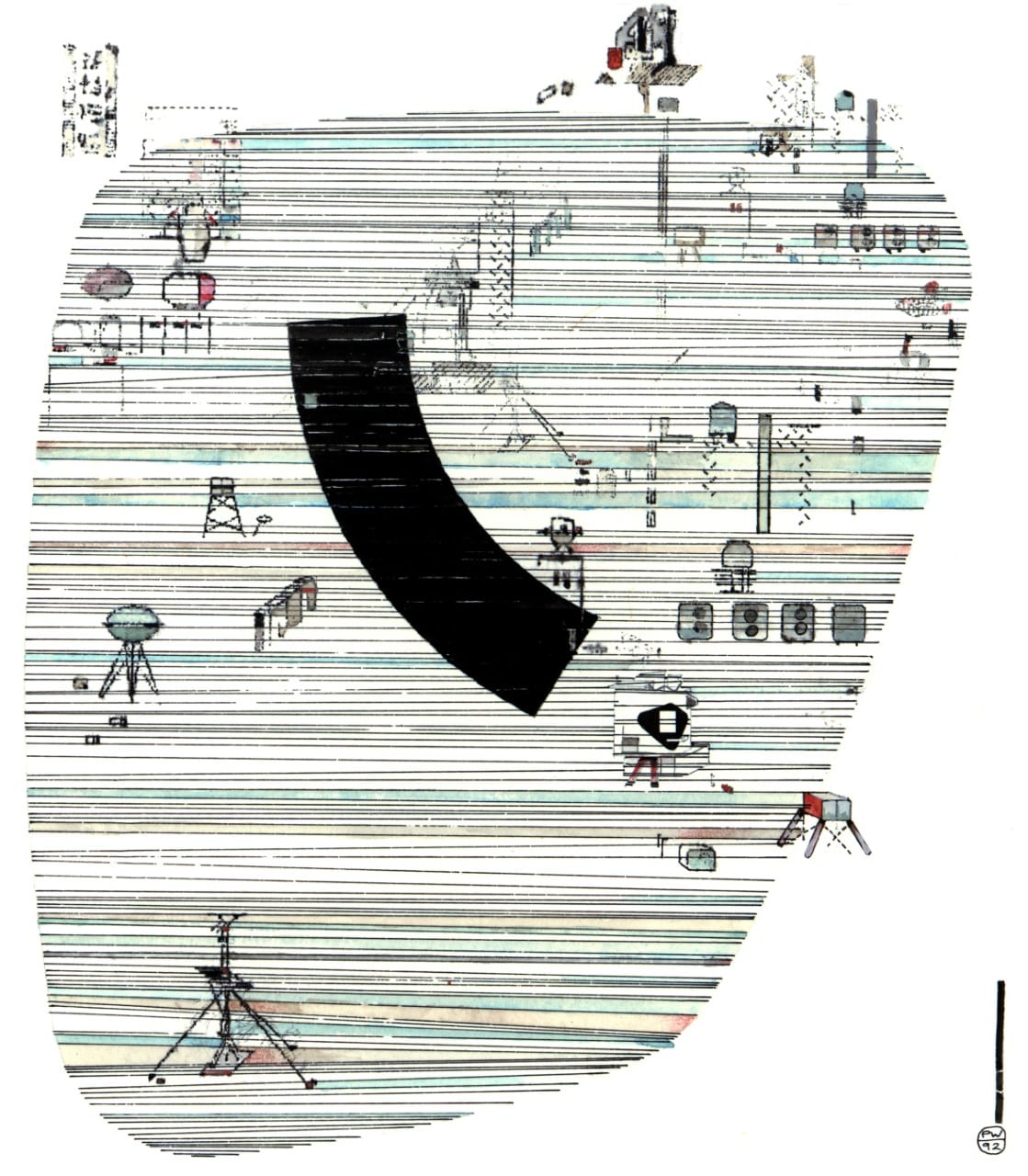

This drift from causal to experimental, from the encyclopaedic object to privileged image, is reversed in the purest re-compositions developed by Jeaneret and Ozenfant between 1918 and 1924. Their self-focussing tableau format, context-less objects suspended in graphic limbo, is as much indebted to the analytical and anthological format of Diderot as it is to Cubism, from which it claimed to have evolved. Here everyday objects coquettishly discard their utilitarian obligations, abandon the world of experience and conspire like a troupe of acrobats to mime an image of the new machine aesthetic. Multiple exposure and merging contours circumvent the limits of linear time and perspectival space, but still like Diderot’s diagrams, submit to a rigorous Cartesian regulation. The study (below) is a fragment of complex iterative evolution. In 1924, after the publication of twenty-eight volumes, the magazine L’Espirit Nouveau collapsed. Le Corbusier (signing ‘Jeanneret’ until 1928) subsequently used leftover L’Esprit Nouveau notepaper for preparative studies for oil paintings. In the case of this study the immediate result was the 1926 Bottle and Book (pink) (FLC143). Such graphic works were in turn rehearsals leading to the post-war plastic forms of Ronchamp and Chandigarh, image ultimately crystallising and recomposing as tangible experiential space, as architecture.

Image courtesy of Bolles+Wilson.

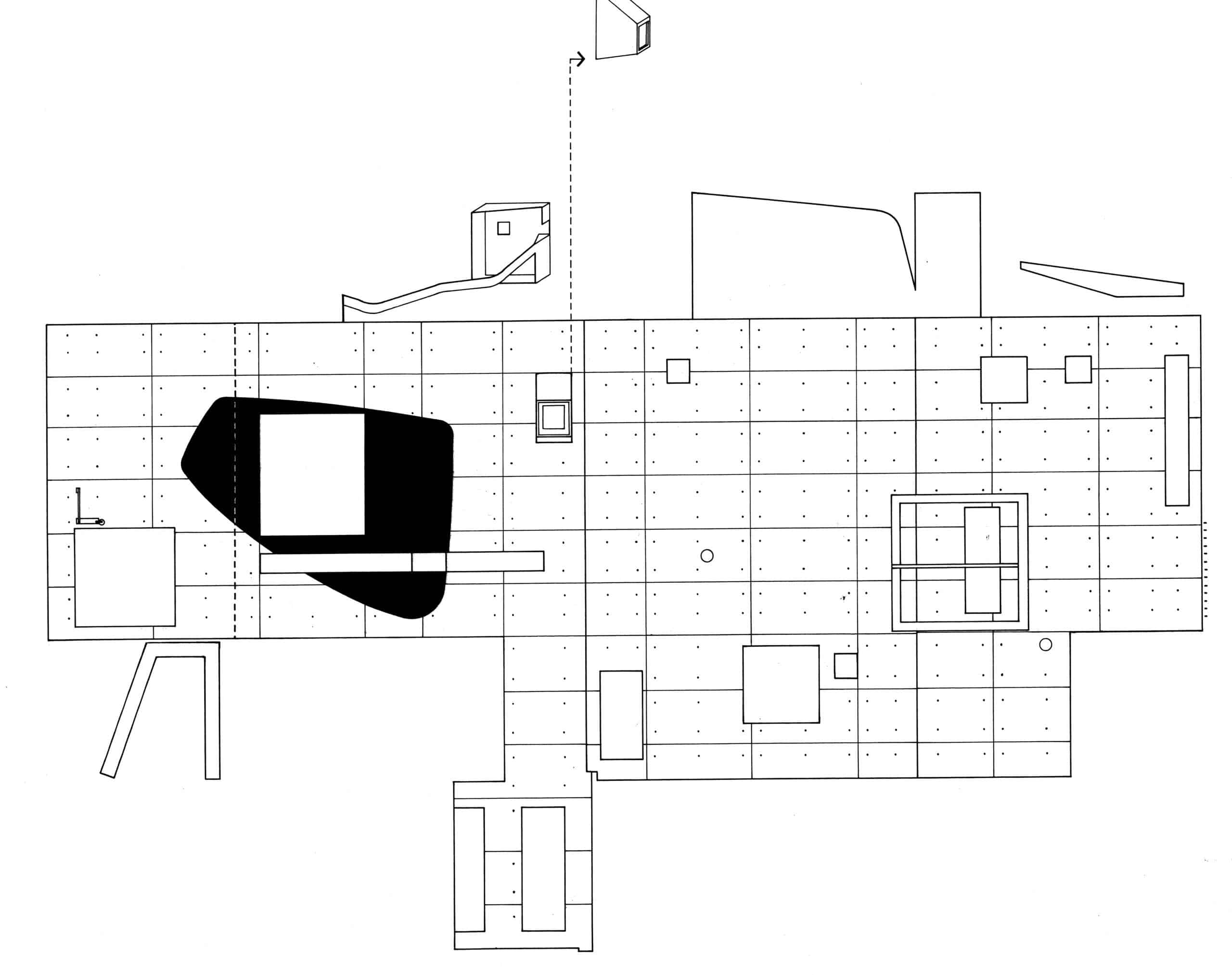

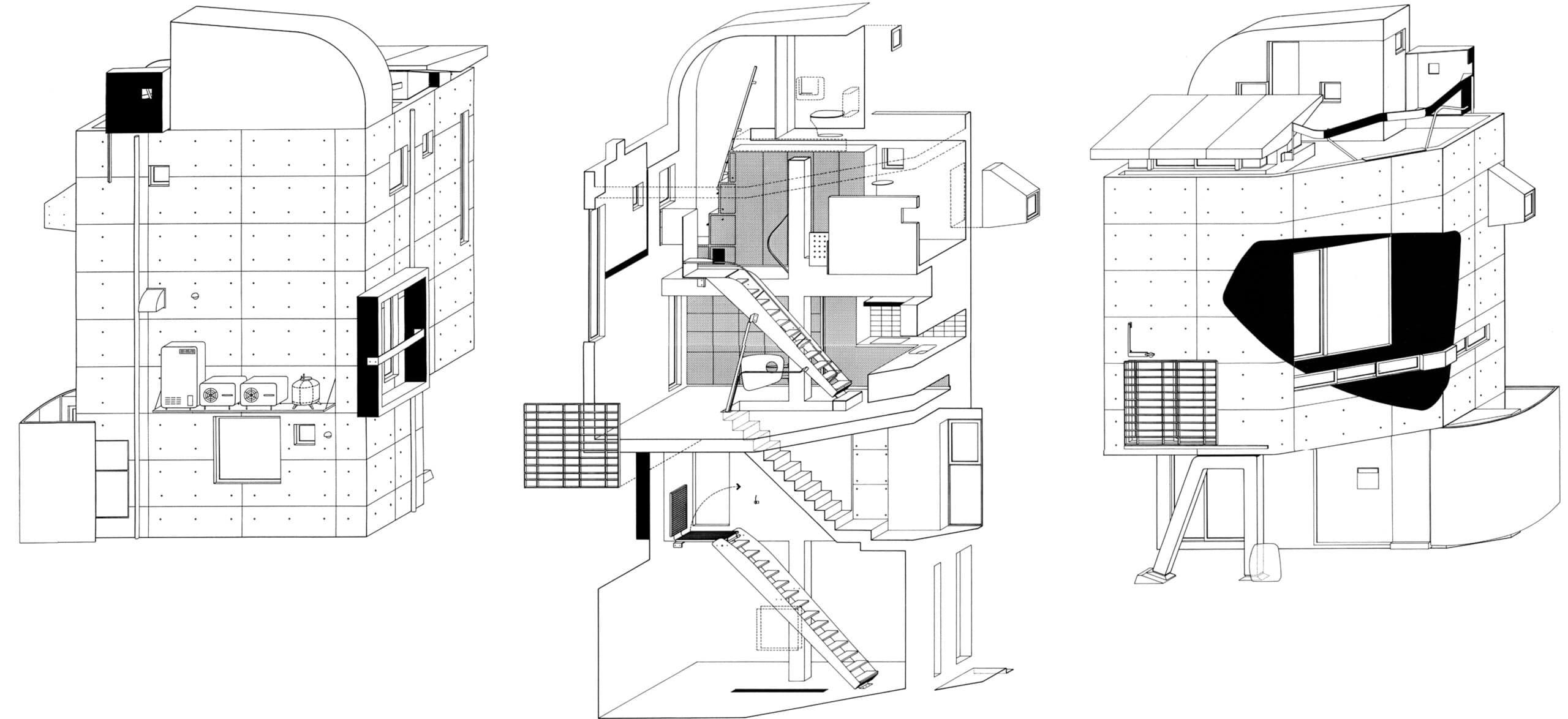

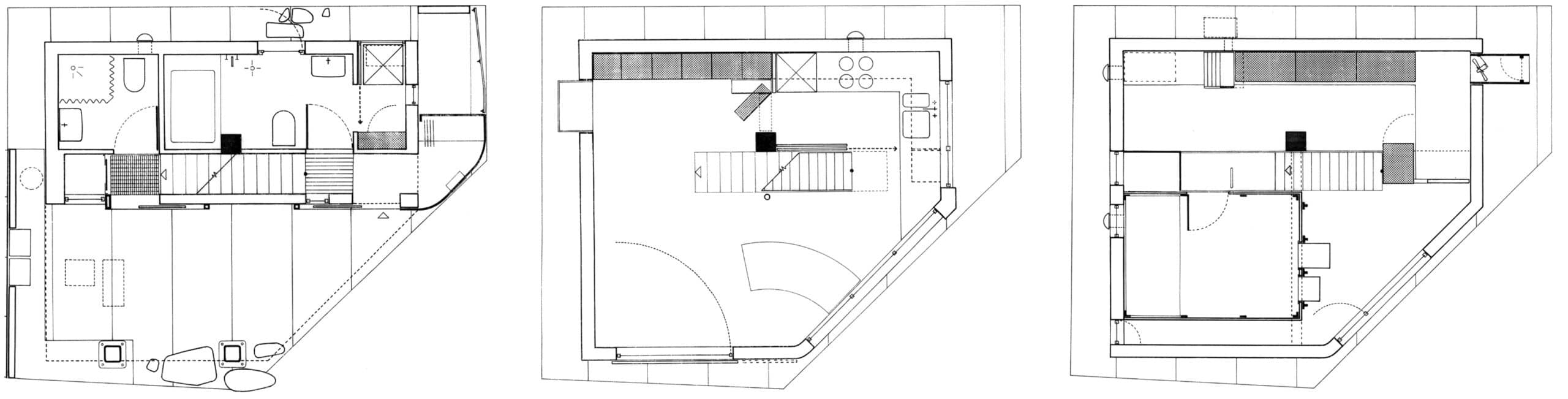

Before Admiral Perry forcibly engaged the Edo world in the techniques and politics of the West, time in Japan was measured by dividing the day and also the night into six hours. The unit itself was elastic, one sixth of a winter day being considerably shorter than one sixth of a summer day. The import of mechanistic calibration, including watch-making techniques like those described in the plates of Diderot, necessitated the invention of complex interlocking mechanisms, geared double clocks, to measure and quantify Japanese phenomenological time. One of these calibrators of subjective time is still to be seen in Tokyo’s Daimyo Clock Museum. For a foreigner to find this museum is no easy matter, the non-repetitive and labyrinthine codings of Japanese cities have more in common with microcircuitry than the legible ordering of the traditional European city. The 1993 Suzuki House also floats somewhere in the matrix of Tokyo, its hovering rectangular discursive facade folds, like a page from Diderot, around the perimeter of its corner site. Like the plates and Le Corbusier’s study it abstains from engaging with its immediate context.

The Encyclopaedist’s dissemination of technique instigated a transition from speculative Enlightenment reason to its industrial application. One hundred years later, purist manifestos aestheticised the industrial as L’esprit nouveau: Modernism. At the time of the Suzuki house’s conception – the last decade of the twentieth century – another perhaps even more wide reaching technological and epistemological paradigm shift was on the horizon. Diderot’s quaint and Le Corbusier’s aestheticised machine was mutating again, bifurcating into innocuous hardware boxes and immaterial but terrifyingly potent software. The boom economy of Tokyo, mythologised by William Gibson’s prophetic Neuromancer or Toyo Ito’s Electronic City (Shinkenshiku Competition 1989 – first prize BOLLES+WILSON) seemed to offer a template for the urban and the physical fallout of this millennial plunge into the virtual. Akira Suzuki’s subsequent book Do Android Crows Fly Over an Electronic Tokyo further evidenced the compatibility and the mutability of Japanese social and spatial codes to the post-digital. The Suzuki House chronicles the conditions of its origin, not as manifesto or image, but as tangible object cast into the Tokyo soup.

Its lens-like facade is both a physical membrane shielding the private inner world and an iconographic ideogram of the emerging material-immaterial dichotomy. Its subtitle, A House Glanced by a Passing Ninja, refers to the black form (Ur-blob), which is not painted on but embossed a whole centimetre into the concrete façade. Ninja is here a Manga-misappropriation, a metaphorical stand-in for ubiquitous but invisible digital dimensions. ‘Glanced’ implies both touch and sight, the pulse of the city both impacting and deflected – a charged oscillation from experiential object to coded poetic image.

First published in A Handful of Productive Paradigms (BOLLES+WILSON, 2009).

Note

We recently spoke to the Suzuki daughter, Aya Suzuki, who grew up in the house, and asked how she explained the black blob to her schoolgirl friends. She answered: ‘Oh thats easy – I told them my house was a Panda’. (Peter Wilson, email to the editors, 15 June 2021)