Hans van der Laan’s Instruments of Thought: Proportion, Architecture, Analogy (2025)

Introduction

A steady trickle of works on Dom Hans Van der Laan has appeared in the years since his passing in 1991. Most important among these, Richard Padovan has presented a compelling argument for the significance of Van der Laan’s theory of proportion through a series of texts, including Dom Hans Van der Laan: Modern Primitive (1994), Proportion: Science, Philosophy, Architecture (1999), and Towards Universality: Le Corbusier, Mies, and De Stijl (2002). These works have been supplemented by a handful of publications by Caroline Voet, whose primary aim is to explain the complicated theory of the Benedictine monk to the architectural world. Voet’s monograph, Dom Hans van der Laan: Tomelilla (2016) gathers many of her thoughts from several shorter articles into a single, sustained reflection. And, Michel Remery’s magisterial work Mystery and Matter: On the Relationship between Liturgy and Architecture in Dom Hans van der Laan (2011) offers a highly developed analysis of the theological foundations of Van der Laan’s architectural theory.

In Hans van der Laan’s Instruments of Thought: Proportion, Architecture, Analogy (2025), the co-authors Tiziana Proietti and Kees den Biesen produce the most recent offering of Van der Laan’s importance. The work presents their own clarification on Van der Laan’s ‘Plastic Number’ to stand alongside Padovan and Voet. But, more innovatively, Proietti and den Biesen argue for the practical value of Van der Laan’s architectural theory. As they summarize, the book ‘is dedicated to three aspects of Van der Laan’s work that can be considered its driving forces, i.e., the search for a theory of architect; the establishment of a three-dimensional system of proportions; and analogy as the mainspring of human thinking.’[1] As they continue, these aspects ‘represent not simply three among many topics or subjects of Van der Laan’s teachings, but a triad of deeply interconnected intellectual strategies that we may consider to be his most important ‘instruments of thought.’[2] Beyond providing an explanation of these ‘instruments,’ the book makes the unique claim that Van der Laan’s theory of proportion has a specific value for educating the next generation of architects.

Proportion

Following an introductory chapter, Chapter 2 begins the exposition (and implied argument) of the book by offering the clearest presentation of Van der Laan’s infamous ‘Plastic Number’ to date. As Proietti and den Biesen tell the tale, Van der Laan began his ruminations on architectural proportion as theories such as Le Corbusier’s Modular built upon the Renaissance allegiance to the Golden Ratio. Van der Laan argues that such theories expose a weakness, for the Golden Ratio can only account for two-dimensional theories of design and not the three-dimensional reality of architecture.[3] He countered this tradition with a phenomenologically based theory that begins with the fundamental activity of humanity to sort all objects of empirical perception into groups via an analogy of similarity.[4]

Following experiments of perception conducted at the Abbey of Roosenberg, Van der Laan established that humans share a tendency to group the sizes of objects per a 1/25 interval of difference. These groupings amount to a creative activity of ‘measuring’ rooted in the mind rather than on a ruler.[5] He records a limited-range of the distinction in sizes between the ‘measured’ groups of objects, and posits that such a difference serves as the quantifiable aspect of a theory of proportion—the ‘Plastic Number’—that can be expressed mathematically as 1+x=x3.[6]

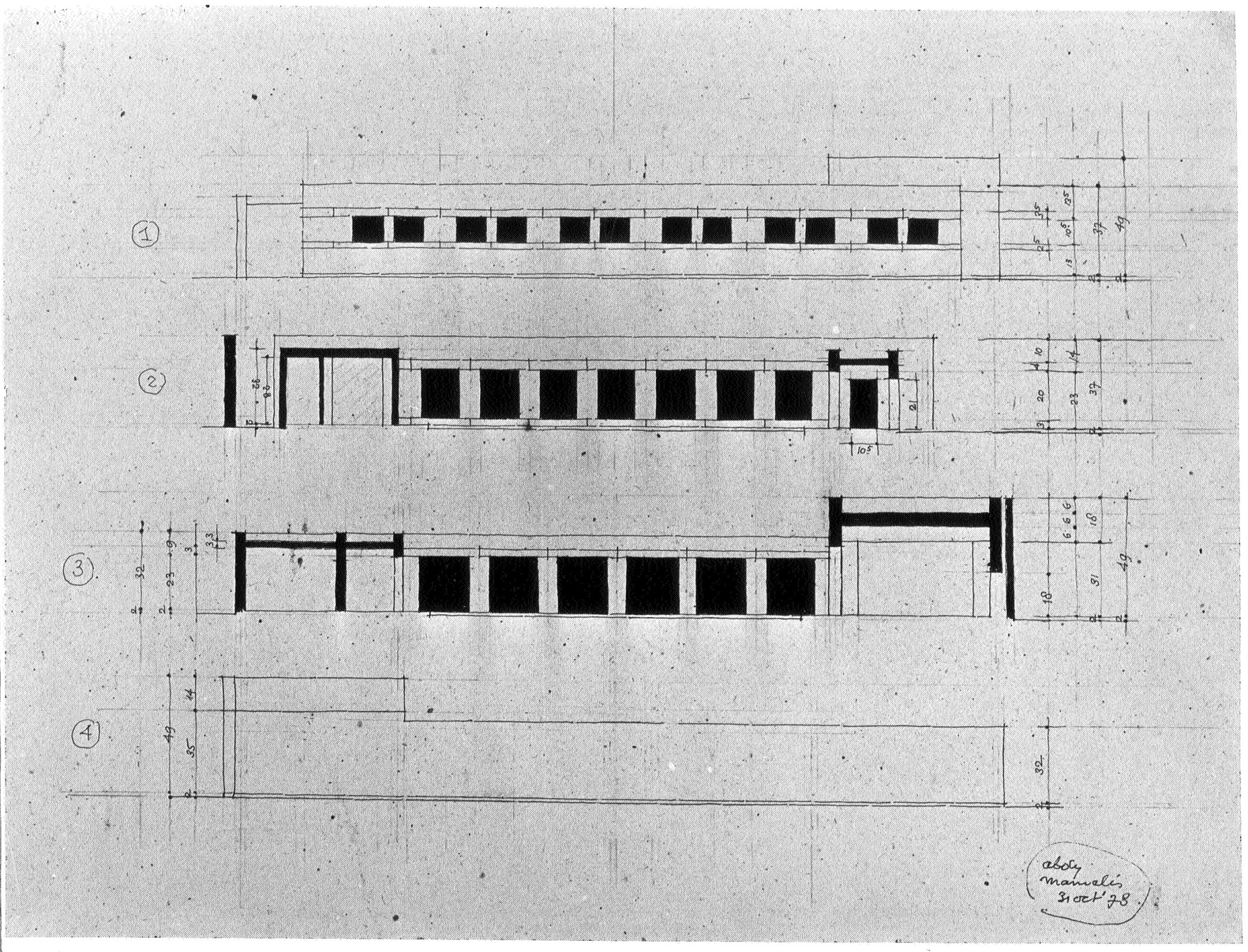

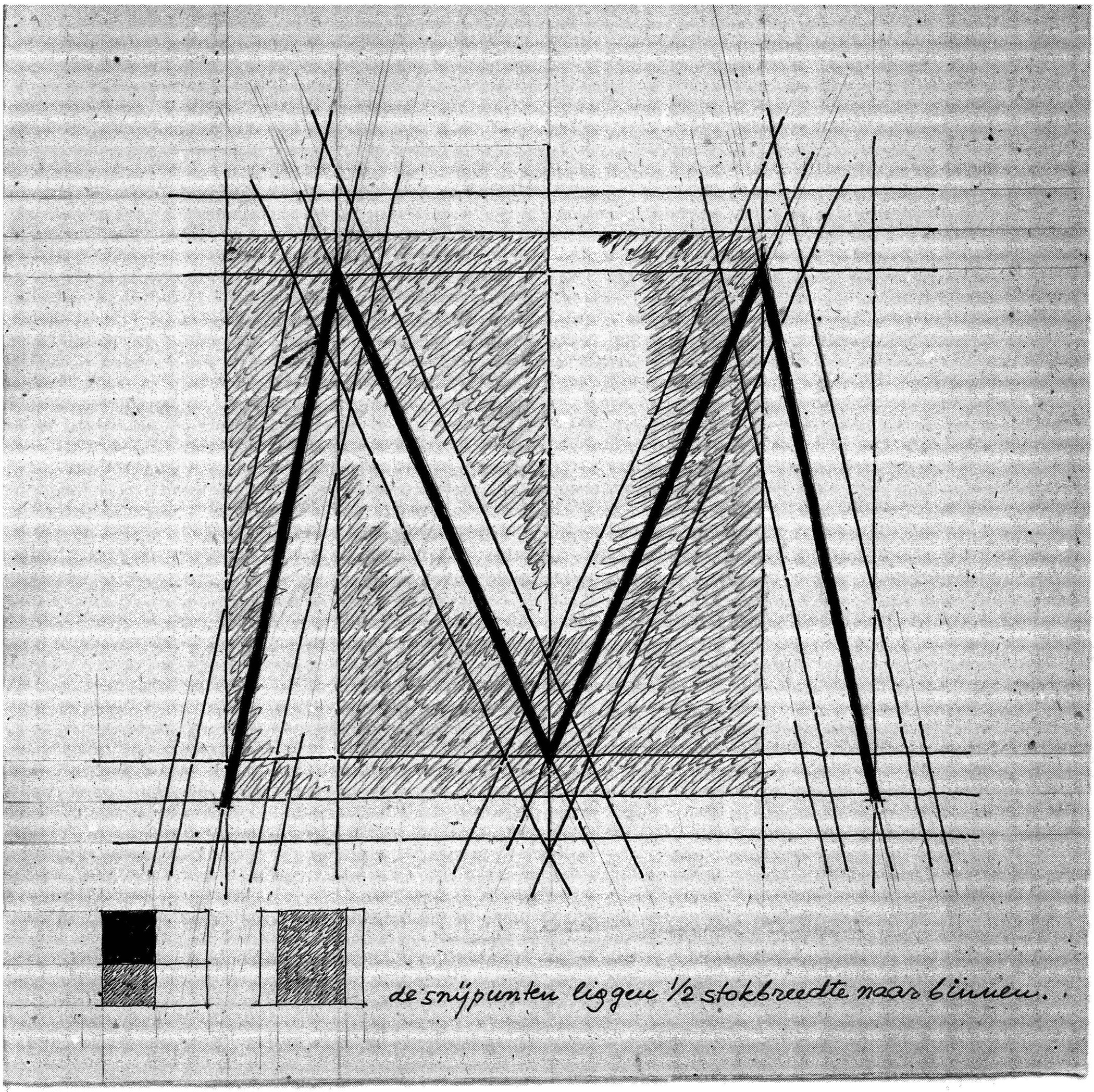

Having established a foundation for a two-dimensional analysis, Van der Laan tasks himself with discerning a three-dimensional proportion. This three-dimensional relation is of another kind than the two-dimensional comparison, rather than a mere extension of it.[7] This move is not easily comprehended. In fact, Van der Laan gave den Biesen permission to add sections to the third Dutch edition of De Architeconische Rumte to explain how this step occurs.[8] Essentially, the degree of difference between any two volumes—what Van der Laan terms the ‘ground-ratio’—can be established by the recognisable difference of any two planes of the volumes, and, therein, not just the two planes of a given elevation.[9] However, all four dimensions of any two volumes establish a typological grouping. These groupings, consisting of either terms of the two volumes (l & w of vol1 and vol2), form a numerical range that Van der Laan references by the ratios of 1:7 to 1:1, with the mean ratio being 3:7.[10]

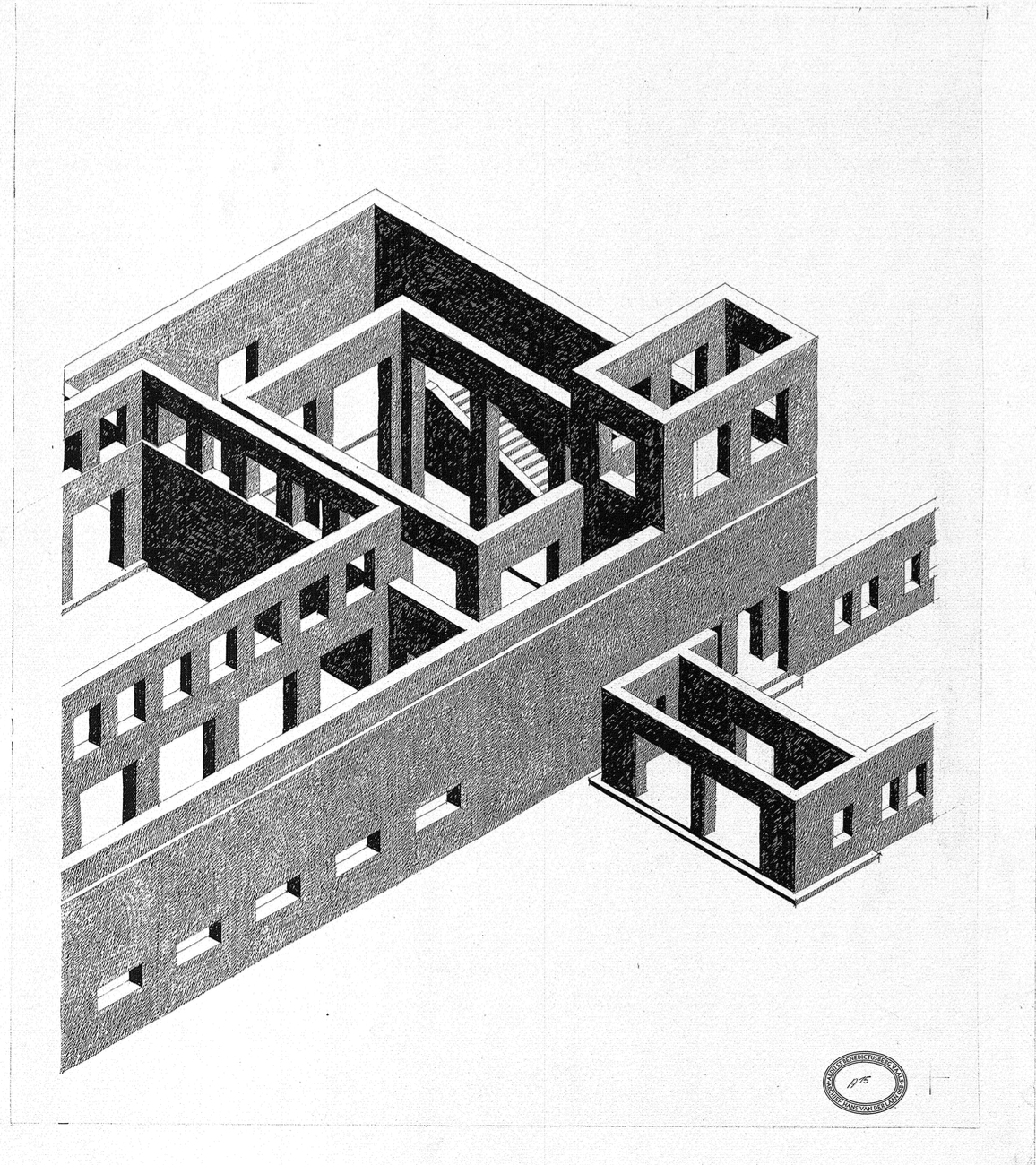

The robustness and dynamics of Van der Laan’s theory, the book argues, are constituted by the fact that the monk has managed to combine all three classical means—the arithmetic, harmonic, and geometric—into a single theory of proportion.[11] Each of the groupings of discernible sizes (from his experiments on perception) is an instance of harmonic means, and their difference from the other groups is an instance of geometric means. That there is an equal number of objects in each grouping of Van der Laan’s experiments, 7, is an example of arithmetic means. As a closing note, the chapter speaks to how Van der Laan utilised the Plastic Number to realise the ‘ordinance’—the architectonic order of each project—and the ‘disposition’—the particularities of each project’s order—when designing his projects at Abdij Roosenberg, Waasmunster, Oosterhaut, and Vaals.

Perception

Chapter 3 transitions into an argument for the practical value of Van der Laan’s theory of proportion. This value, in short, is that his theory can serve as a foundation for courses in visual training in architectural programs at the university level. The chapter begins in a similar manner to the previous one, mapping out the number of programmes that instituted some form of visual training via proportion in architectural schools during the first half of the twentieth century. These would include the Bauhaus school, which developed a pedagogy from Wassily Kandinsky’s Point and Line to Plane as well as the Illinois Institute of Technology, where Mies Van der Rohe helped to inaugurate a similar programme.[12,13]

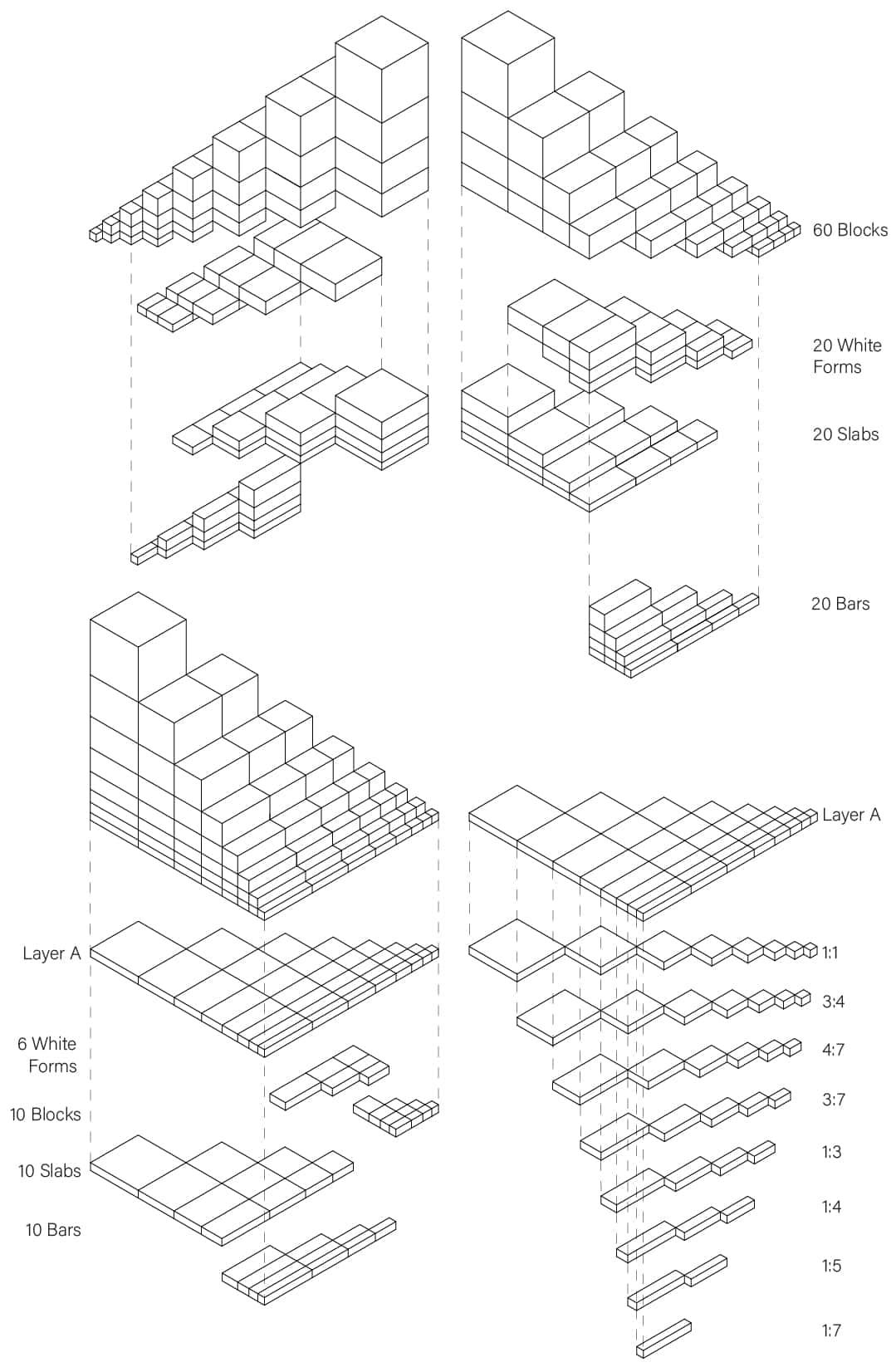

The difference of a pedagogy formed Van der Laan’s theory is, once again, the three-dimensional character of his Plastic Number. Where other programmes of visual training rely on two-dimensional analysis of forms, Van der Laan proposes to utilize two sets of volumetric models he terms as the ‘abacus’ and the ‘morphotheque.’[14] The abacus is a set of spherical objects, like mini-columns, that are arranged according to the ‘ground-ratio’ developed in the Plastic Number. The ‘morphotheque’ is similar, only using rectangular volumes that arrange in a pyramid-like gradation. Van der Laan’s only prescription is for students to ‘play’ with the various sizes of shapes, arranging them in different ways, in order to experience their visual and physical interaction. As a unique feature of the book, Proietti and den Biesen provide over forty pages of possible exercises which could stimulate this play.

The book also provides evidence for the efficacy of a Plastic Number pedagogy that comes, in part, via the interaction with theories in the fields of gestalt psychology and cognitive science and, in part, by evidence from trial runs of such a pedagogy in a joint-venture between the University of Oklahoma and the Salk Institute (under the guidance of Proietti and Sergei Gephshtein).[15] The findings of these experiments and theoretical conclusions, among other things, show a change in the way participants categorise objects of perception in general. This reorientation, then, can be seen in the design of architectural students as they develop an almost innate sense of proportional relations.

Analogy

The final chapter of the book returns to an exposition of Van der Laan’s theory, this time focusing on a set of analogies he draws between our artistic activities and our interaction with the material world. The chapter draws together the key points of the book to show how a practice of visual training with the Plastic Number shapes the entire realm of perception. The goal of such a transformed vision is not merely aesthetic but serves the function of deepening our understanding of the conditions of existence for the sake of a heightened quality of cultural production.

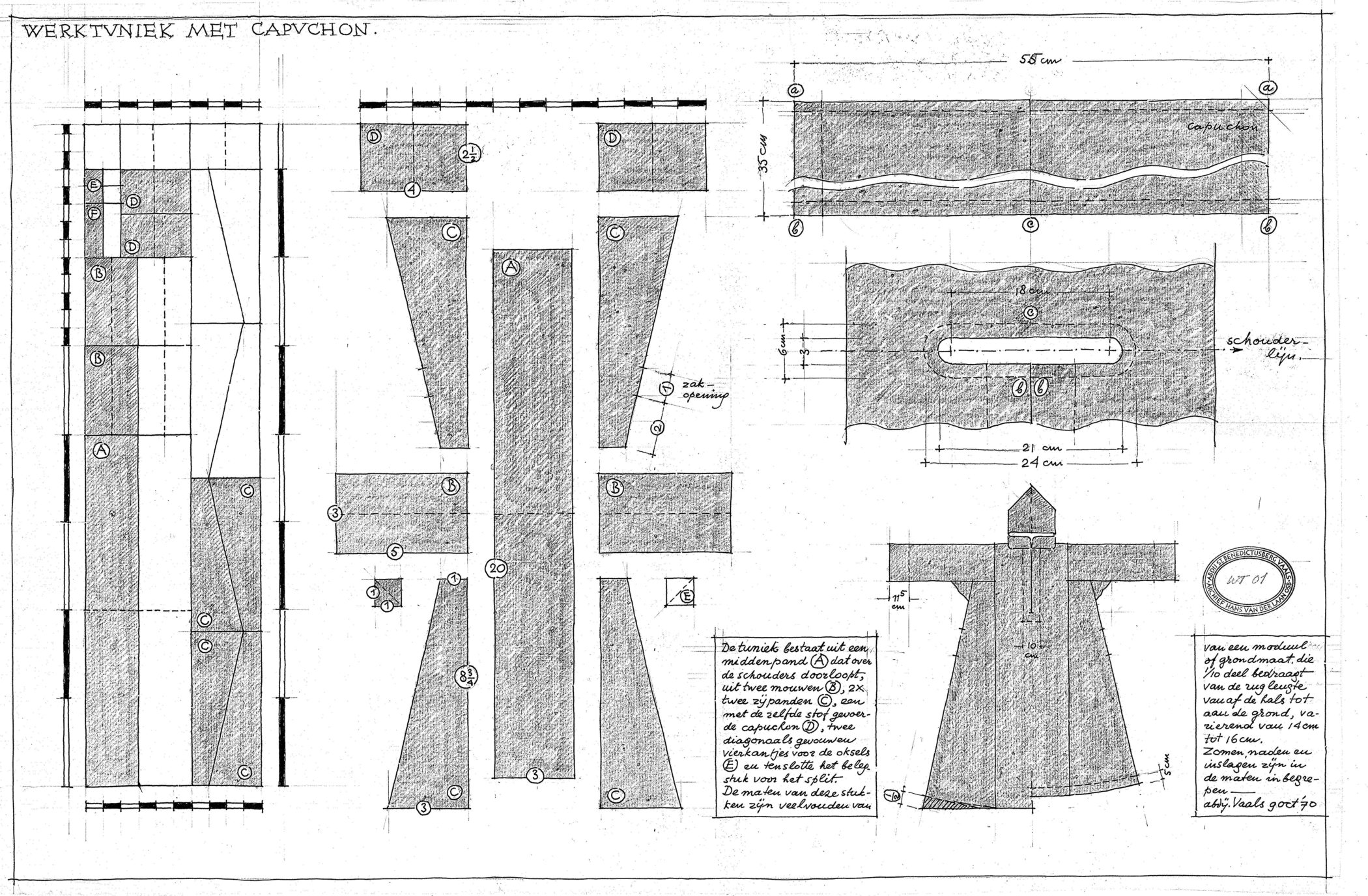

Van der Laan highlights three concepts of cultural artefacts that meet this demand: ‘functionality,’ ‘expressiveness’ (or visible intelligibility), and ‘monumentality’ (or the ‘ability to convey meaning’).[16] The chapter traces how Van der Laan employed these concepts in his design of the Naalden House, as well as his design of various other cultural artefacts, ranging from clothing to ritual vessels to typefaces. This chapter closes with a discussion of the theological assumptions which drive Van der Laan’s ‘analogy’ of cultural production, focusing on the neo-Platonic roots of Christian theology with the hope of ‘[restoring] dignity to the arts.’[17] The book concludes with two annexes, the first being a detailed comparison of the Plastic Number with the Golden Section, the second, a guide to the exercises for a pedagogy of visual training laid out in Chapter 3.

Remark: A Theological Anxiety

Hans Van der Laan’s Instruments of Thought succeeds in two general aspects. First, as stated above, it is the clearest explanation of the Plastic Number to date, even surpassing the exceptional work of Padovan. The authors do a remarkable job at simplifying the transitional steps of the theory as they trace its development from the most mundane objects (rocks, trees) through the complexities of architectonic space to the multivalence of a metaphysical analogy. This, alone, makes the book valuable. Second, Proietti and den Biesen make a compelling case for the value of integrating proportion and visual training into the pedagogies of architectural programs. This two-sided approach—drawing from Van der Laan’s theory and empirical findings from cognitive science—presents an interesting account of the monk’s legacy. This section, in particular, will be augmented by further findings in Proietti’s work with the Salk Institute.

The single point of dissonance I find with the authors is the tone of the book when it comes to the question of Van der Laan’s religion. It is quite clear from Van der Laan’s biography that a strong theological foundation runs through all of his architectural theory and the buildings it produced. All of the secondary works on Van der Laan have emphasised this point. Padovan, for example, highlights how the Benedictine principle of moderation, the ‘middle way’ of that monastic order, plays a performative function in Van der Laan’s design. That is, the particular proportion Van der Laan selected for the architectonic order of the Abbey at Vaals (3:7) is the ‘middle’ form of the Plastic Number’s range.[18] Further, Padovan explains that the key principle of Scholastic epistemology—nihil est in intellect quod non sit prius in sensu (‘nothing is in the intellect which is not first in the senses’)—is the founding principle of Van der Laan’s account of the function of architecture for general perception and the possibility for its contribution toward visual training.[19] In a similar manner, Voet points out how the principle of Ima Summis (‘the lowest within the highest’) from Pseudo-Dionysius is what allows Van der Laan to reconcile the opposite terms of his metaphysical analogy.[20] This should not be surprising, since Dionysius exerted a monumental influence on medieval architecture. (The Abbot Suger, after all, developed the Gothic style at the Abbey of St. Denis.) Above all, Remery’s extremely detailed work has presented an irrefutable account of the importance of theology and faith in Van der Laan’s artistic productions.

The present book does not ignore this facet of Van der Laan’s theory (Beisen himself lived in the Abbey at Vaals as a monk for a time), but when the topic is broached, it is, in most cases, couched by an anxiety that such a claim will diminish the value of Van der Laan. The book reassures its readers that the main ‘principles formulated by Van der Laan are not declared from a pre-existing philosophy or doctrine,’ but rather from his empirical research.[21] Although, later, the book explains the reliance on empirical perception comes from ‘adopting philosophical terminology developed from Thomas Aquinas,’ it also states that, ‘for methodological purposes, Van der Laan presented’ a theory ‘strictly limited to phenomenological exploration.’[22] When expositing a passage in which Van der Laan explicitly speaks of God as the only ‘real’ creator of poetic activity, the book explains away the theological importance of this issue as a fragment of ‘Europe’s ancient cultural and intellectual traditions.’[23] Finally, in its closing pages, we are told that, ‘For those who are not Christians or not believers, the language used by Van der Laan…may seem tinged with a certain religious ideology….Yet Van der Laan intended to write about the forms of religious rituals in the most general way possible,’ wholly apart from the particularities of the religion and monastic order to which he vowed his life.[24]

In my view—speaking as a theologian of a post-metaphysical tradition—it seems strange to exercise so much caution around the possible effects of Van der Laan’s personal faith and Christian influences. It seems that over three centuries of critiques on religious dogmatism could have moved at least the academic world to a place where theologians can admit ‘humans can be human without God’ and architects can accept that architecture can be architecture even with religious impulses, if not theological foundations.[25] It further seems that the last century of post-structural de-construction would have stilled any innate worry that the intentions of an author (or architect) are mystically transmitted into and through cultural artefacts. I can personally attest that even though Van der Laan’s major works were all ecclesial, they are quite harmless when it comes to any contagion of religion.

My point here is not to critique the book nor to outright challenge these particular statements. I suspect that den Biesen, in particular, has a special authority to make such claims. The point is much more to highlight that the tone of this theological anxiety stands in contrast to the other major works on Van der Laan. Perhaps this is another of the book’s many contributions to this literature. Or, more likely, the safeguarding of his architectural theory from theological contamination better supports the argument for the pedagogical value of Van der Laan’s theory and its consonance with contemporary cognitive science. Every interpretation is guided by a context, and the interpretation of Van der Laan present in this book, resonates with assumed judgments of its context. What I have called a theological anxiety is not intended to speak to the facticity of Proietti and den Biesen’s interpretation, for their claims can be taken as fitting under a certain hermeneutical light as it radiates from a certain context. It is rather a diagnosis of the context in which the book is composed.

It also seems rather clear to me that Van der Laan’s claim that ‘liturgical form had universal significance’ was more of a continued influence of Catholic metaphysics than a prevenient embrace of multi-culturalism.[26] In fact, the central thrust of his theory appears as a rather predictable outcome of the analogia via negative that runs through St. Benedict, St. Denis, and St. Thomas. Much more radical are Van der Laan’s contemporaries Wassily Kandinsky, in whom his Eastern Orthodox tradition is only scantly visible in his theory or art, or Paul Tillich, whose Lutheran theology owes much more to F.W.J. Schelling’s concept of Geist than to Martin Luther himself.

Once again, I see the book’s theological anxiety as a symptom of the larger discourse rather than a deficiency of the book itself. Perhaps whatever concern drives this anxiety would be better served by simply remaining silent on the question of God in Van der Laan, which could certainly be accomplished even while explaining the mechanics and value of his theory. That being said, Van der Laan raises interesting questions for the growing field of theology of architecture. I find structural parallels, for example, between the work of the existentialist Thomist theology Jacques Maritain’s view of art laid out in The Frontiers of Poetry (1927) and Murray Rae’s more theoretical exploration in Architecture and Theology: The Art of Place (2017) would certainly benefit from dialogue with Van der Laan. Due to the theological anxiety, these sorts of questions and parallels will find less value in Hans Van der Laan’s Instruments of Thought than in Remery’s or Padovan’s work.

Nevertheless, Proietti and den Biesen do a marvellous job of explicating Van der Laan’s Plastic Number, which is the jewel of his monastic contemplation. Because of its targeted aim of exposing the pedagogical value of this theory of proportion, this may not be the conclusive work of Van der Laan, but it is certainly an irreplacable contribution to his continued legacy, and a work with which all subsequent publications on Van der Laan will undoubtedly engage.

Notes

- Tiziana Proietti and Kees den Biesen, Hans van der Laan’s Instruments of Thought: Proportion, Architecture, Analogy (London: Routledge, 2025), 1.

- Ibid., 12.

- Ibid., 22.

- Ibid., 28.

- Ibid., 27.

- Ibid., 29.

- Ibid., 34-8.

- Ibid., 38.

- Ibid., 40-1.

- Ibid., 47.

- Ibid., 42.

- Ibid., 63-4.

- Ibid., 65-6.

- Ibid., 84-142.

- Ibid., 8; 82-3.

- Ibid., 152.

- Ibid., 174.

- Richard Padovan, Dom Hans Van der Laan: Modern Primitive, (Amsterdam: Architectura and Natura Press, 1994), 82.

- Padovan, Modern Primitive, 48-50.

- Caroline Voet, ‘Between Ima Sumis and Nearness: Dom Hans van der Laan’s Roosenberg Abbey as an Example of a Contemporary Space of Worship,’ Interiors 6, no. 3, (2015): 265-6.

- Ibid., 56.

- Ibid., 167.

- Ibid., 168.

- Ibid., 172.

- Eberhard Jüngel, Gott als Geheimnis der Welt. Zur Begründung der Theologie des Gekreuzigten im Streit zwischen Theismus und Atheismus, 8. Auflage ed. (Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), 1977), 18.

- Proietti and den Biesen, van der Laan, 168.

C.M. Howell worked in architecture before receiving his PhD in theology from the University of St Andrews.

– C.M. Howell