Heinrich Kulka and Adolf Loos

On 7th July 2025, an exhibition dedicated to architect Heinrich Kulka opened at the Ringturm Exhibition Centre in Vienna, titled Heinrich Kulka (1900–1971) – The Spatial Plan as a Design Method, focusing on Kulka’s European work, both with Adolf Loos and as an independent architect. It was curated by architect and writer Adolph Stiller with the assistance of Jan Sapák and Stephan Templ. The hall was packed that night to see an architect who, in many ways, remains relatively obscure beyond a small circle of admirers. This speaks of the current growth in interest regarding the young architects who worked alongside Loos, of whom Kulka indisputably was the most significant.

Jindřich Kulka was born in 1900 in Litovel, Moravia (modern-day Czechia). He began working with Loos in Vienna in 1919, adopting the Germanic name Heinrich, and, with the exception of a brief interlude in Germany, remained by his side until Loos’s death in 1933. During that time, Kulka worked on many of Loos’s most celebrated works, including Villa Rufer (1922) in Vienna; Knize menswear (1927) in Paris; the unbuilt Maison Josephine Baker (1927) in Paris; Villa Moller (1927–28) in Vienna; and the Albert Matzner menswear shop (1929–30), also in Vienna. His role extended beyond the usual employee-employer relationship. Kulka was the best man at Loos’s wedding to his third wife, Claire Beck, while his own wife, Hilda Beran (Beranová), was Loos’s practice manager. Following Loos’s death, Kulka was responsible, alongside Grethe Hentschel, for saving much of Loos’s archive, ignoring his instructions to destroy it. Today, this archive forms the basis of the Albertina Museum’s collection of Loos’s drawings.

Kulka’s role in Loos’s practice changed from around 1928 onwards, as Loos became increasingly incapacitated. In the unbuilt Haus Bojko (1929–30), the drawings are jointly signed. In Kulka’s 1931 monograph on Loos—the first ever book on Loos—Kulka credited himself as a ‘mitarbeiter’ on Villa Khuner (1930), in Kreuzberg, Payerbach, Austria. The word can be translated as employee, but here is better interpreted as ‘collaborator’ or ‘co-worker’. In this book, Kulka introduced the world to the word ‘raumplan’, a conceptual framework used to explain Loos’s unique three-dimensional spatial organisation, albeit the term is one which Loos himself never employed in his extensive writing.

During these later years, one sees Kulka’s growing creative influence on Loos’s work, resulting in fundamental changes to it. One notes the introduction of striking interior colour schemes—Kulka’s distinctive palette of strong yellows, greens and reds—and a more youthful and relaxed relationship with current strands of modernity—the most obvious example being the increased areas of transparent glazing.

As Loos grew frail and Kulka assumed ever greater responsibility in the practice, moments of friction occurred between the two architects over the rightful accreditation. Kulka often had to produce work under enormous time pressures, with limited information or last-minute instructions given by Loos, who was often travelling or undergoing medical treatment. Their most well-documented dispute centred on the Vienna Werkbund houses (1932) in Hietzing. Kulka begged Loos for direction, but due to the need to deliver the scheme on time for the Werkbund opening, Kulka designed the houses unaided. According to eminent scholar Burkhardt Rukschio, ‘[Loos] was furious that his initial plan for the Werkbund came too late, his fault of course, and by Kulka’s solution.’[1] When Loos saw the realised work, he considered that it bore so few of his own ideas that he nearly removed his name from the exhibition, only to be persuaded to leave it in at the last moment by organiser Josef Frank.

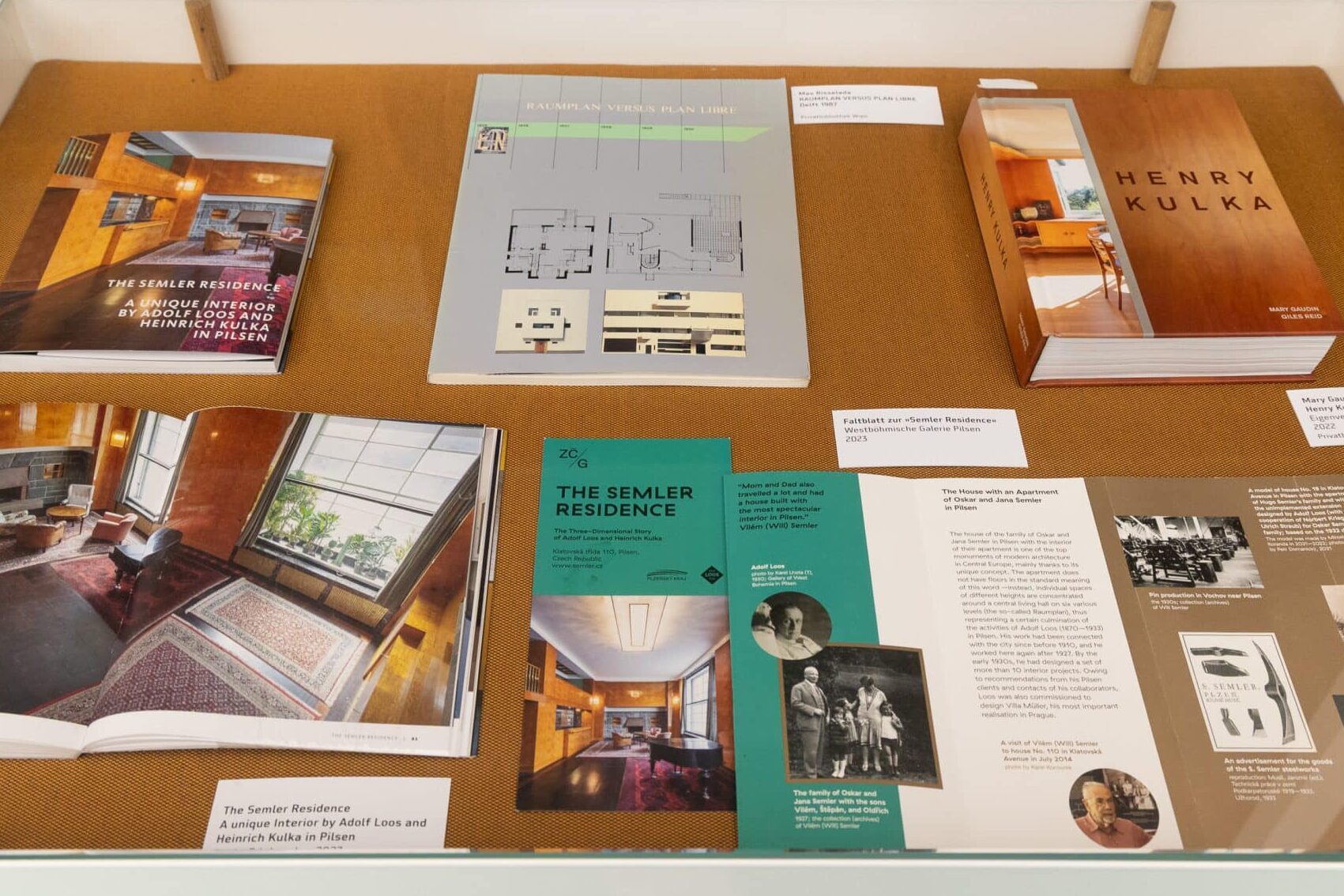

Loos died while the design for Apartment Semler (1932–34) in Pilsen, Czechia was in its infancy. Its spectacular restoration (reopening September 2022) has activated a fundamental reassessment of Kulka. Pilsen is host to a concentration of restored Loos interiors (Brummel, Kraus, Vogel, and others), and Loos architectural tourism has become one of its major attractions. The city authorities co-credit Loos and Kulka with the design. Some, on the other hand, argue the work is Kulka’s alone.[2] For now, and unless definitive proof emerges to the contrary, joint attribution is reasonable. After all, the clients had engaged Loos, not Kulka and were seeking a Loos design, a sign of great prestige within the tight-knit Jewish community of Pilsen. What is not in dispute is that Kulka received, at best, only the most basic of information from Loos to take forward. It speaks to Kulka’s talents that he developed these ‘bones’ into one of the most persuasive of all Loosian works, perhaps second only to Villa Müller (1930) in Prague, in terms of scale, ambition, material richness, and sophisticated exploration of the raumplan.

After Loos’s death, Kulka maintained an office in Vienna and opened a second one in Hradec Králové, located in the east of modern-day Czechia, where Hilda’s family resided. Kulka saw himself as Loos’s main disciple and advocate, proudly continuing Loos’s ideas, most notably with Villa Kantor (1932–34) in Jablonec (formerly Gablonz), Czechia. Today, this work stands as the apotheosis of the idea of a compact, cubic house conceived with a raumplan.

Kulka continued working and building in Europe until 1938, surprisingly late for a Jewish architect, when he fled Nazi persecution to England. After failed attempts to emigrate to the United States, he made his passage to New Zealand, his wife and children arriving separately. Here he again changed his name, this time to the anglicised Henry. Although he designed several private houses during his early New Zealand period, his principal activity was as chief architect from 1940 until 1960 at Fletcher Construction, New Zealand’s largest building company. Working in a team of engineers, he was responsible for the design of a huge array of commercial and industrial projects, from prosaic factory programmes through to workers’ accommodation, churches, and even corporate headquarters, where his Loosian sensibility is clearly on display.

However, despite the freedom he was given, Kulka again found himself fulfilling the role of a vital but ultimately ‘anonymous’ employee. Following retirement from Fletchers at the age of 60, he restarted his private practice, designing single-family houses in Auckland, the Waikato and Wellington, often for fellow émigré clients who appreciated his pedigree and ideas, which sat outside the mainstream of New Zealand modernism. He was active until shortly before his sudden death in 1971.

Following this, his daughter Maru shipped much of his archive to the Albertina in two large tea chests. Rukschio notes that:

‘They were full of his plans on transparent paper, thinly rolled and generously sprayed with DDT. When I tried to flatten them, I had no chance as the weeks long transport by sea had turned the plans into permanents and I got problems on my skin and lungs from the insecticide. The restoration department was doing research how to overcome these problems which were not resolved when I left the museum in 1974’.[3]

Here, this material has lain in the Albertina’s basement, untouched ever since. Under European law, copyright of this work—held by his New Zealand descendants—does not expire until 70 years from his death, and access to its contents has been cut off to most researchers. Even the team behind the restoration of Apartment Semler never gained permission to reproduce its contents. Instead, they relied on Pilsen city archives and other sources, which makes their results even more remarkable.

Although Kulka is often noted as a modest man, he was not without ambitions of his own, nor a desire to secure his legacy. He grew concerned towards the end of his life that his work would be forgotten. In the late 1960s, he had sent material to art historian Vera Běhalová, today revered for her role in documenting and saving Loos interiors in Czechoslovakia during the Communist era—often at considerable personal cost, including jail when convicted of spying on the state. Her research on Kulka appeared in the German architectural journal Bauforum in 1974.[4]

Before her death in 2010, Běhalová gifted her Kulka archive to fellow Czech Jan Sapák, whose article on Villa Kantor in Domus (1991), helped bring Kulka back into the light after a lengthy period of neglect.[5] It is from this separate, hitherto unknown archive that Kulka’s European work re-merges so strongly in this exhibition, combined with Stiller’s considerable efforts to track down and visit the buildings themselves and bring together material from disparate sources. What comes as a shock is the inclusion of so much previously undiscovered material, particularly Kulka’s drawings, which almost never find their way into the public realm.

It is immediately apparent that Kulka was a gifted draughtsman. His delineation of complex designs appears effortless. Typically, Kulka presents a perspective view of a room or an architectural element, a particular window, say, alongside a decisive detail of it. The client or builder is given an overview of the whole and the part. These details are drawn on quite small pieces of paper, in pencil rather than pen. Line weight, material description and lettering, all show his drafting prowess, unparalleled technical ability and deep understanding of a wide range of construction techniques—concrete, steel, stone, plaster, fine metal and glass. These drawings also reflect his intimacy with Loos’s philosophy of detailing—for example, in the way that at Apartment Semler, flush detailing is never actually quite flush. Materials are consistently offset by a fraction, around 2mm, introducing tolerance and subtle separation, carried rigorously around the whole room.

Kulka clearly enjoyed timber joinery detailing and ironmongery, which later dovetailed with New Zealand’s dominant wood-based construction techniques. All his work is characterised by inventive small-scale proposals to provide comfort and delight: fold-and-slide doors, drawers, secret mirrors, and immaculate panelling. This mindset is best on view at both Semler and Kantor, but the same fascination with small-scale engineering emerges earlier, in the green metal sliding shutters running on forged steel wheels and rails at Landhaus Khuner. In the exhibition, one sees this in a drawing for the Holzner House (1937) in Hronov, depicting a Loosian adaptation of the English bay window. Kulka sets dense planting in front of it and uses frosted glazing to deny the view out, while creating a complex double-glazed system introducing two lines of inward-opening single-glazed casements with bespoke milled timber and flat bar steel.

Loos produced only sketches. Notably, he did not like to draw. By comparison with most modern ‘masters’ such as Aalto, Le Corbusier or Mies, Loos drew quite crudely. From these basic plans full of scribbles and notations, his employees were expected to develop his ideas into works of incredible sophistication. At times, especially from the mid-1920s onwards, after Loos left Vienna for Paris, the process relied heavily on correspondence between Loos and his Vienna-based staff.

Yet curiously, the role of the working drawing in Loos’s architecture is never present in discussion of his work. This reinforces the misconception that construction drawings do no more than represent the dry, analytical side of architecture and have little bearing on the design, other than to transcribe the idea into built reality. The role of the detail drawings as a creative artefact is ignored, in line with the assumption that such material would likely have only limited appeal to the wider public. In this exhibition, by contrast, technical drawings become keys to decipher the schemes presented; one only wishes that even more of Kulka’s drawings could be on display.

A further revelation from this show is how many buildings and interiors survive in Europe. Some shop interiors were previously only found in long-forgotten publications from the 1930s. I knew that the exterior of the Teichner Mountain House (1934–36) was no longer original but believed it had been more recently altered internally as well, beyond recognition. Thankfully, this proves incorrect. Although the Kawafag Weekendhaus (1930–31) in Dresden no longer exists, seeing photos of it dating from as recently as 2007 is a great surprise and forces a reassessment of the idea promoted in New Zealand that Kulka had to ‘learn weatherboards’ after arriving there.

Following the acclaimed restoration of Semler, plans are progressing to restore Villa Kantor. However, as with all things related to Loos, controversy lurks. There is lively debate as to the extent to which the current proposals could undo the terrible changes made to it during the communist era, when it was turned into flats with a common stair. Many experts believe that the glorious entry sequence should be fully reinstated, for which the superlative Semler restoration provides the gold standard.

If in Europe, Kulka’s work is on the rise, in New Zealand, by contrast, the situation is largely depressing. Here, there is a near-complete absence of legal protection for historic monuments, especially the city’s postwar modernism. Most of Kulka’s commercial work for Fletcher Construction has gone. A few of the projects which he carried out independently for the Fletcher family survive, in varying states of preservation; for instance, his interiors in the Fletcher home in Penrose, Auckland, have just been rehabilitated. The Halberstam House in Karori, Wellington, a beautiful if modest work, still inhabited and in immaculate condition, is in the process of being listed.[6] However, the New Zealand houses Běhalová used to illustrate her article have been either demolished or so radically altered as to be unrecognisable—a fate common to so much of his work.

The greatest body of surviving works is in the hands of Kulka descendants who own three or four houses. Their portfolio includes the modest but stunning Kulka family home in St Heliers (1944), Auckland. It is lined internally in plywood—Kulka’s economic substitution for the rare veneers he could readily call upon in Austria and Czechia. It has never been possible to understand this work from a purely local architectural perspective, so strong are its Loosian roots. This ‘otherness’ is one reason for its obscurity in New Zealand; the other is that it remains inaccessible and unpublished.

As ever, there is more to uncover and in New Zealand the added urgency of a race against time. This illuminating and most engaging exhibition therefore stands as a major milestone in these efforts. It underscores the professionalism, pride, scholarly and financial resources which Vienna gives to its architectural forebears. Moreover, it represents a ground-breaking moment in the understanding of both Adolf Loos and Heinrich Kulka, or as known in his adopted New Zealand, Henry.

Notes

- Pers. Comm, email from Burkhard Rukschio November 7, 2022.

- Kulka is noted as the sole architect of Apartment Semler in his Wikipedia page, which judging from the copyright restrictions, appears to have been predominantly authored by the Kulka Estate.

- Pers. Comm, email from Burkhard Rukschio November 7, 2022.

- Vera Běhalová, ‘Bietrag zu einer Kulka-Forschung’, Bauforum, Issue 7, Volume 43 (1974), 22–31.

- Jan Sapák, ‘Heinrich Kulka: Villa Kantor a Jablonec 1933-34’, Domus, 726 (1991), 100-107.

- Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga is currently working on a proposal to include the house on the New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero (the List).

All images courtesy Architektur im Ringturm.

*

Giles Reid is a New Zealand-born architect. His book, Henry Kulka, with photographer Mary Gaudin, was the first published on Kulka. His forthcoming book on architect Claude Megson comes out this April, while his latest built work is the new home for gallerist Sadie Coles, on Savile Row, Mayfair.