Metabolism of a Dwelling

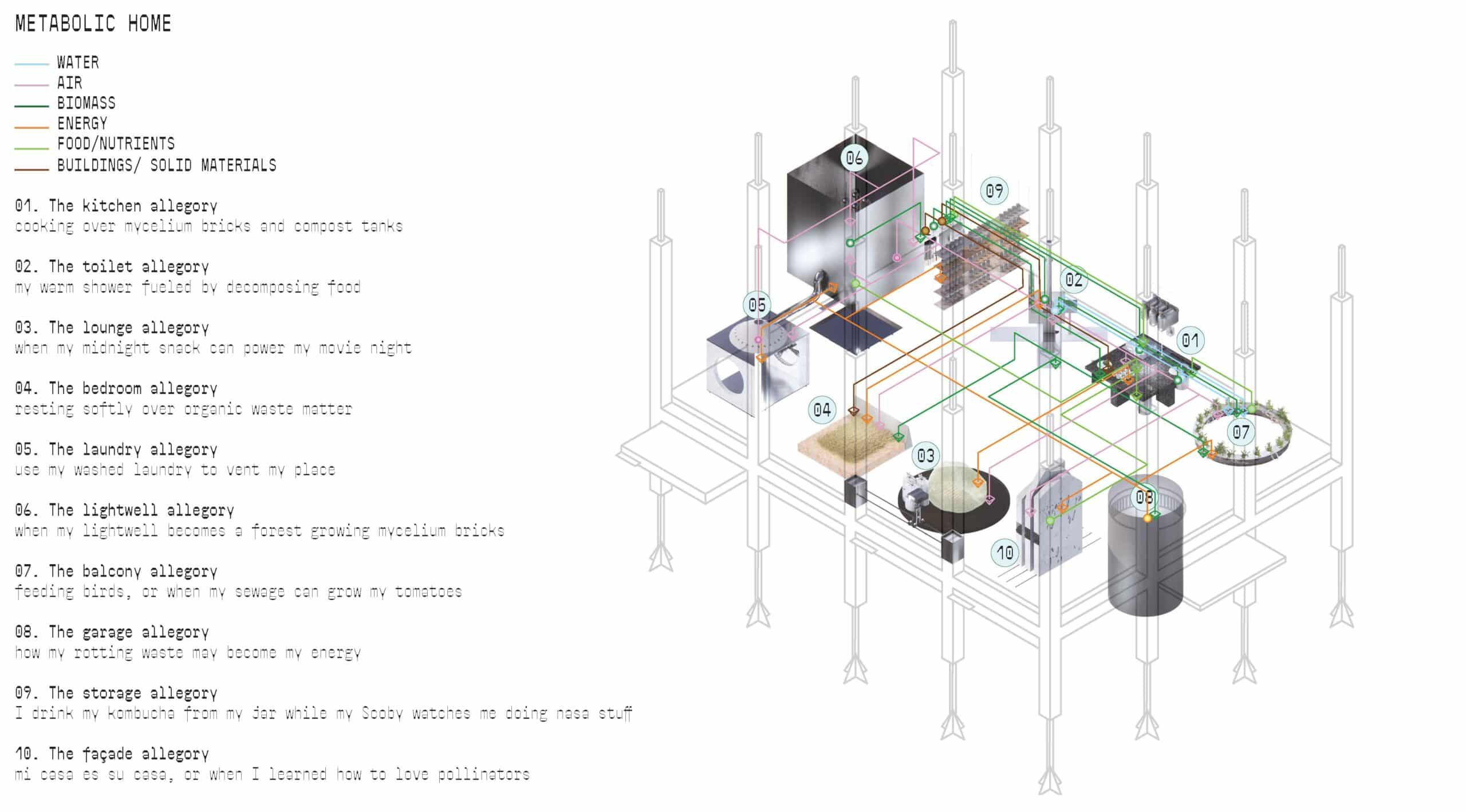

Surrounded by the world’s most advanced robotic technologies, electronic dance music, and solemn tonal soundscapes lies The Metabolic Home, an installation by Lydia Kallipoliti and Areti Markopoulou currently on view in the Arsenale at this year’s Venice Biennale. The project constructs a densely configured environment in which everyday domesticity—cooking, sleeping, washing, cleaning, storing—unfolds into visible systems of metabolic exchange. Composed within a concrete grid of nine discrete yet communicative spatial cells—kitchen, lounge, toilet, bedroom, laundry, storage, garage, balcony, and lightwell—the project renders the home as a circulatory system through which matter, energy, and atmosphere are rerouted, reprocessed, and metabolised across interdependent zones.

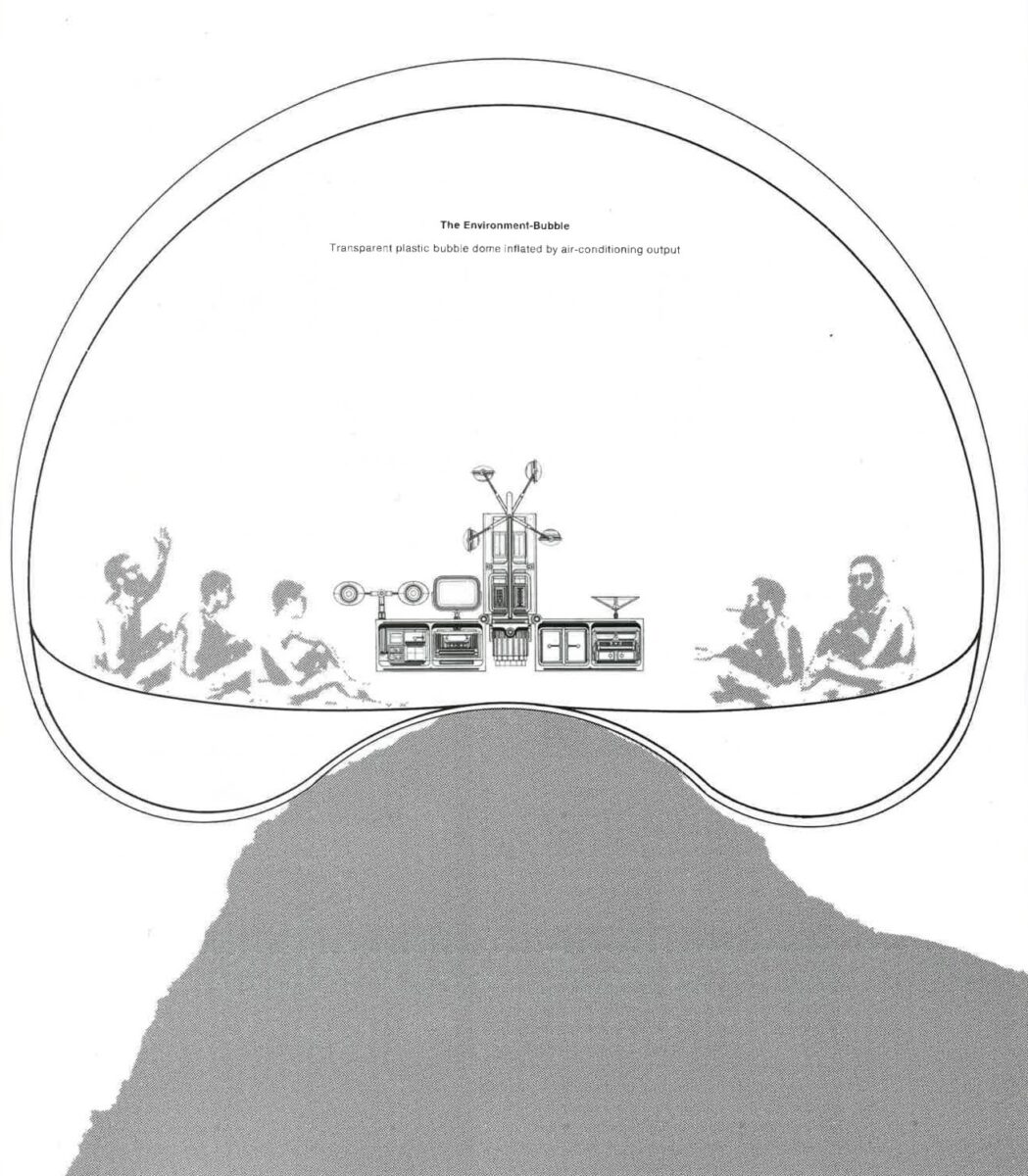

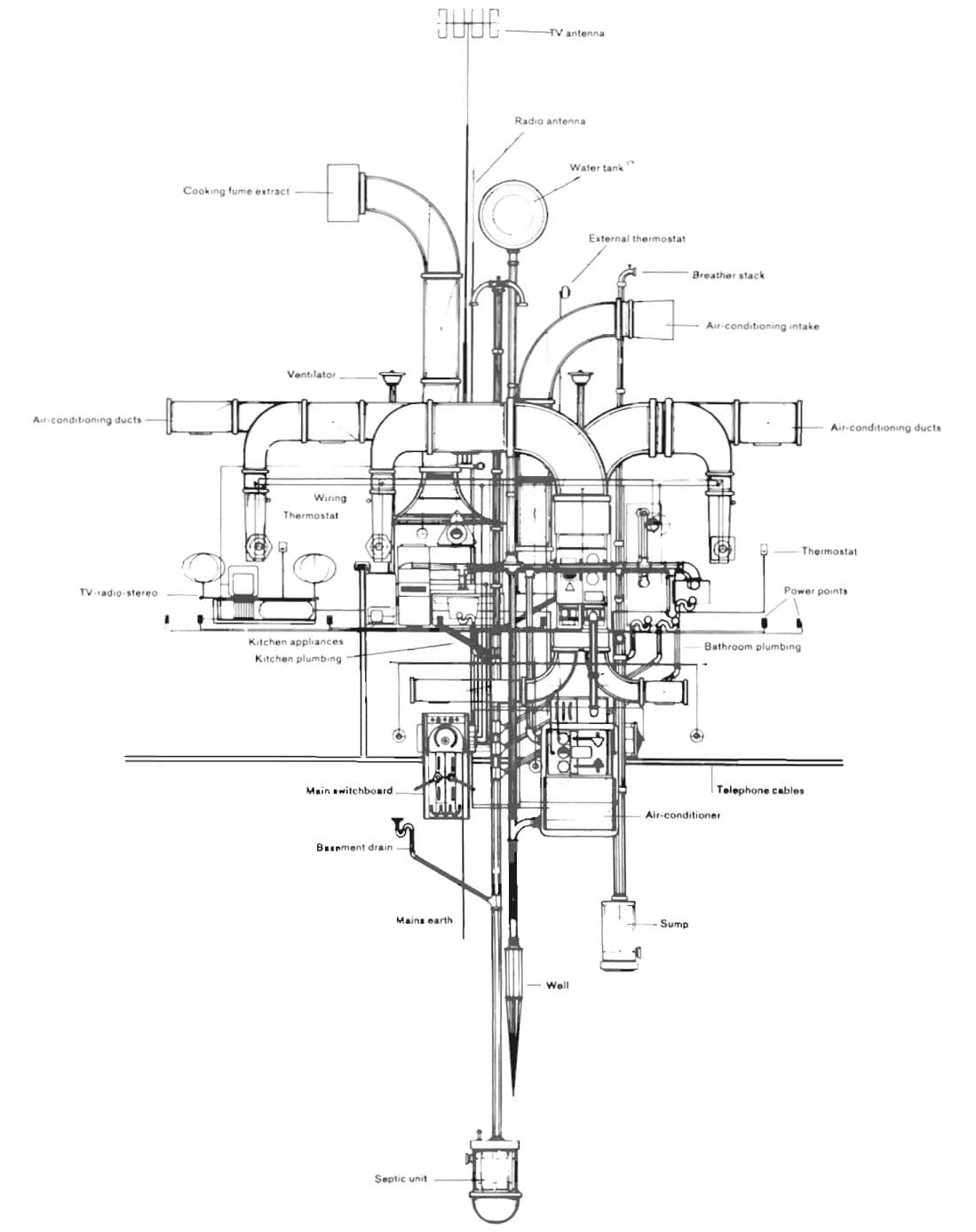

The Metabolic Home is not, strictly speaking, a domestic typology. In his 1965 essay, ‘A Home is Not a House’, Reyner Banham questioned why a house should provide enclosure at all: ‘when it contains so many services that the hardware could stand up by itself without any assistance from the house,’ he wrote, ‘why have a house to hold it up?’[1] Kallipoliti and Markopoulou respond not with a sealed, inflatable ‘anatomy of a dwelling’—as famously drawn by Francois Dallegret in Banham’s essay—but with a proposition that renders infrastructure as form. Rather than a domestic type, they construct a programmatic archetype: a tangle of biomechanical ‘guts’ where cohabitation metabolises and performs. Its enclosure is secondary to the flows it contains.

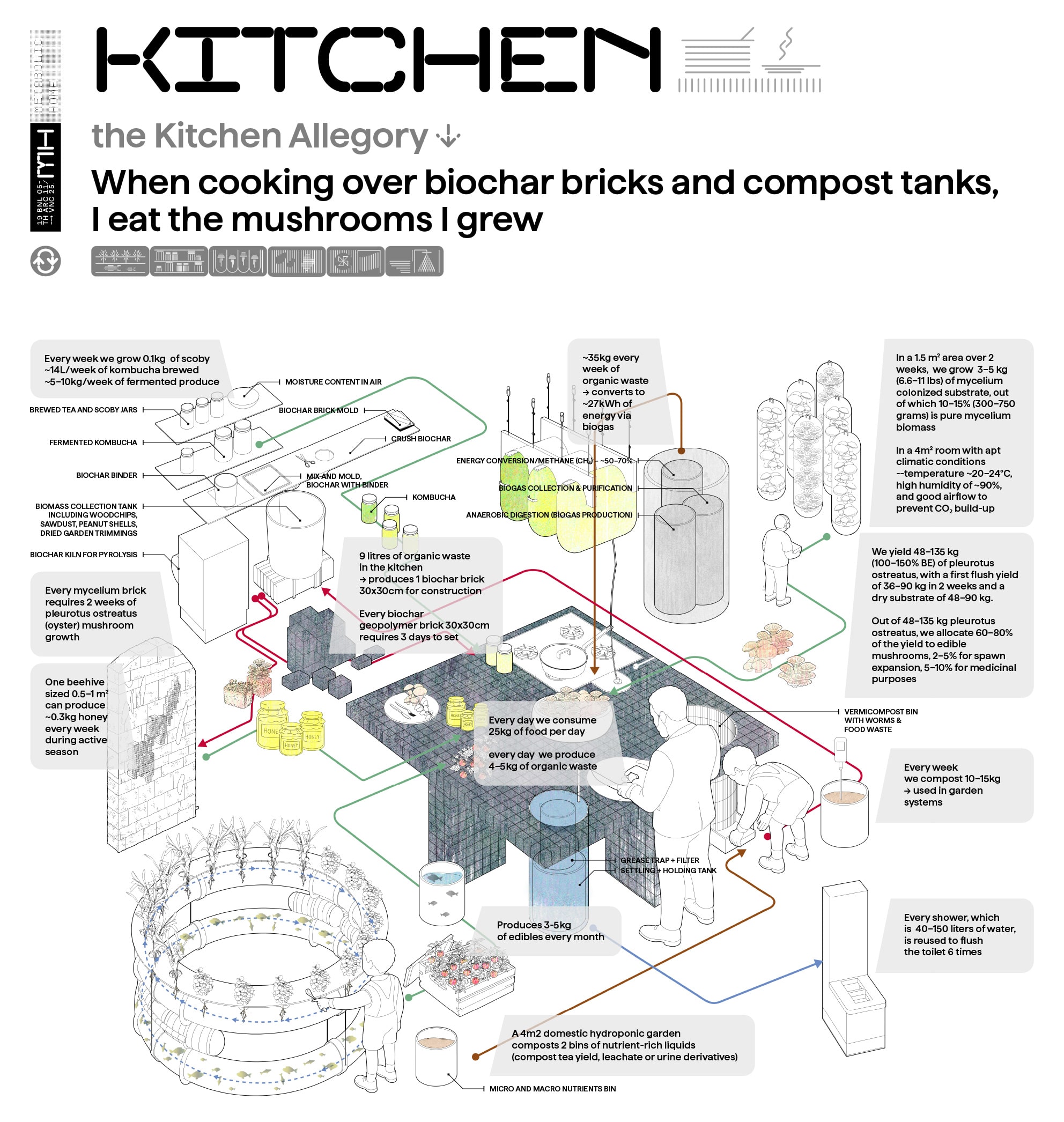

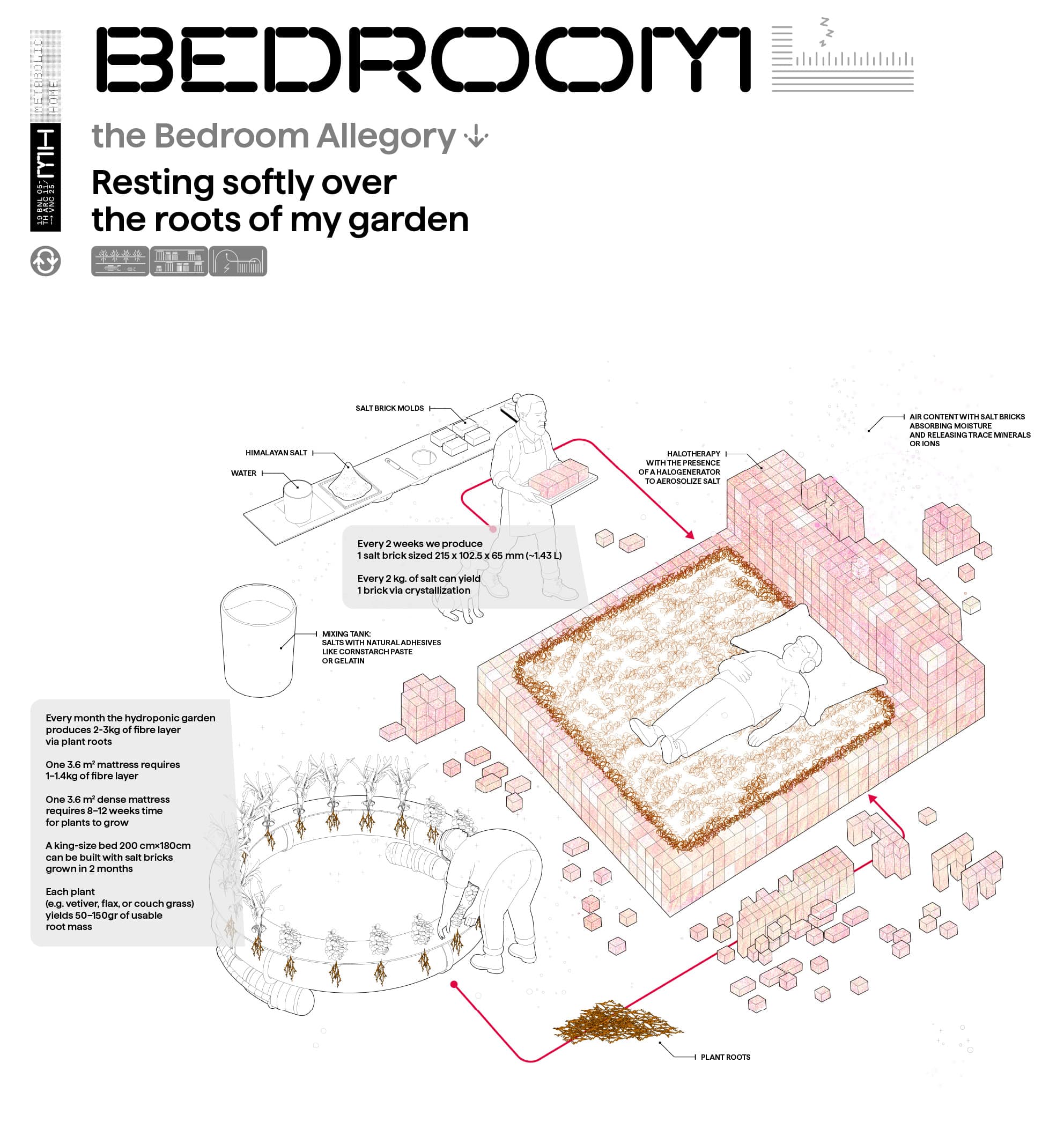

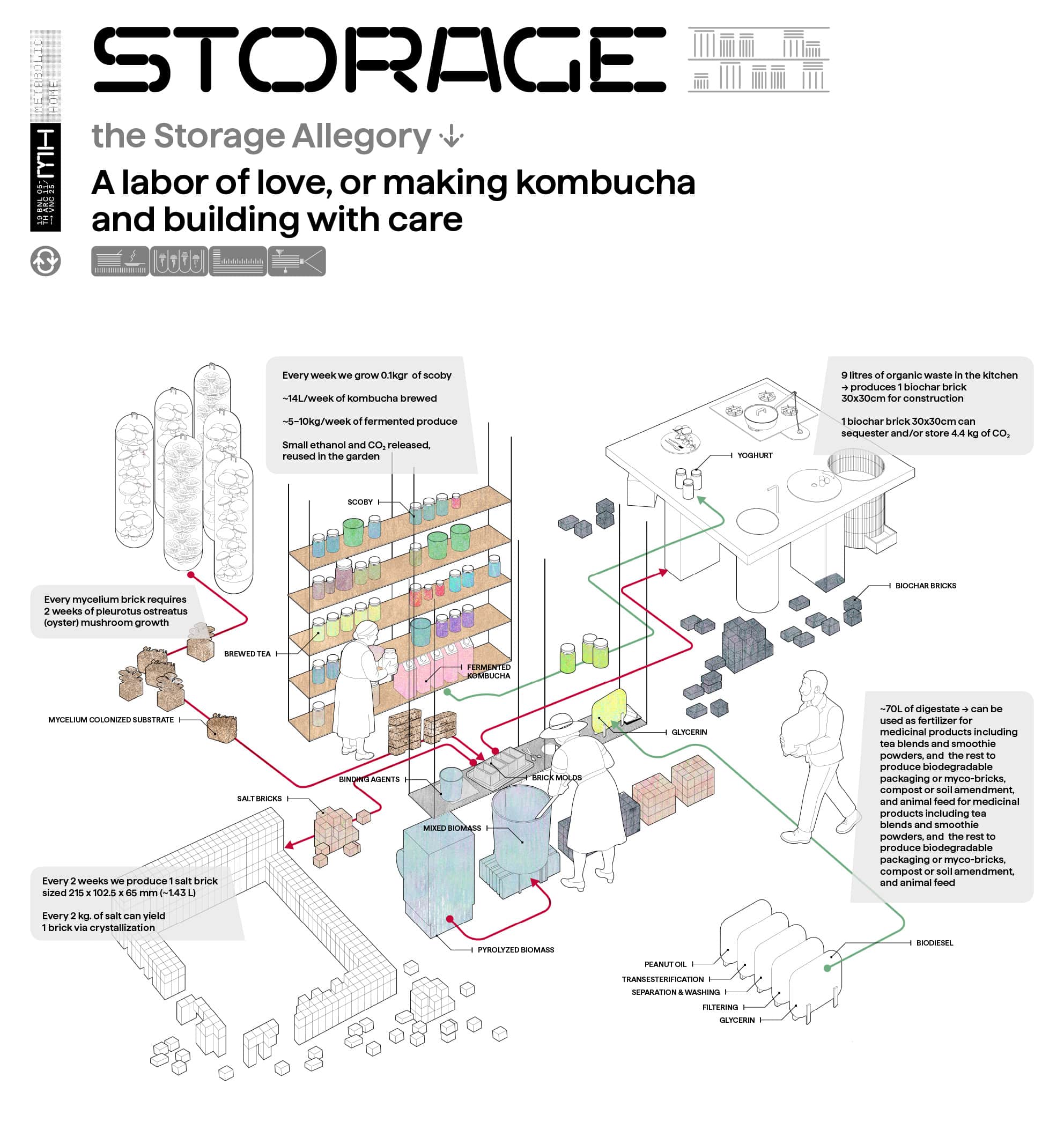

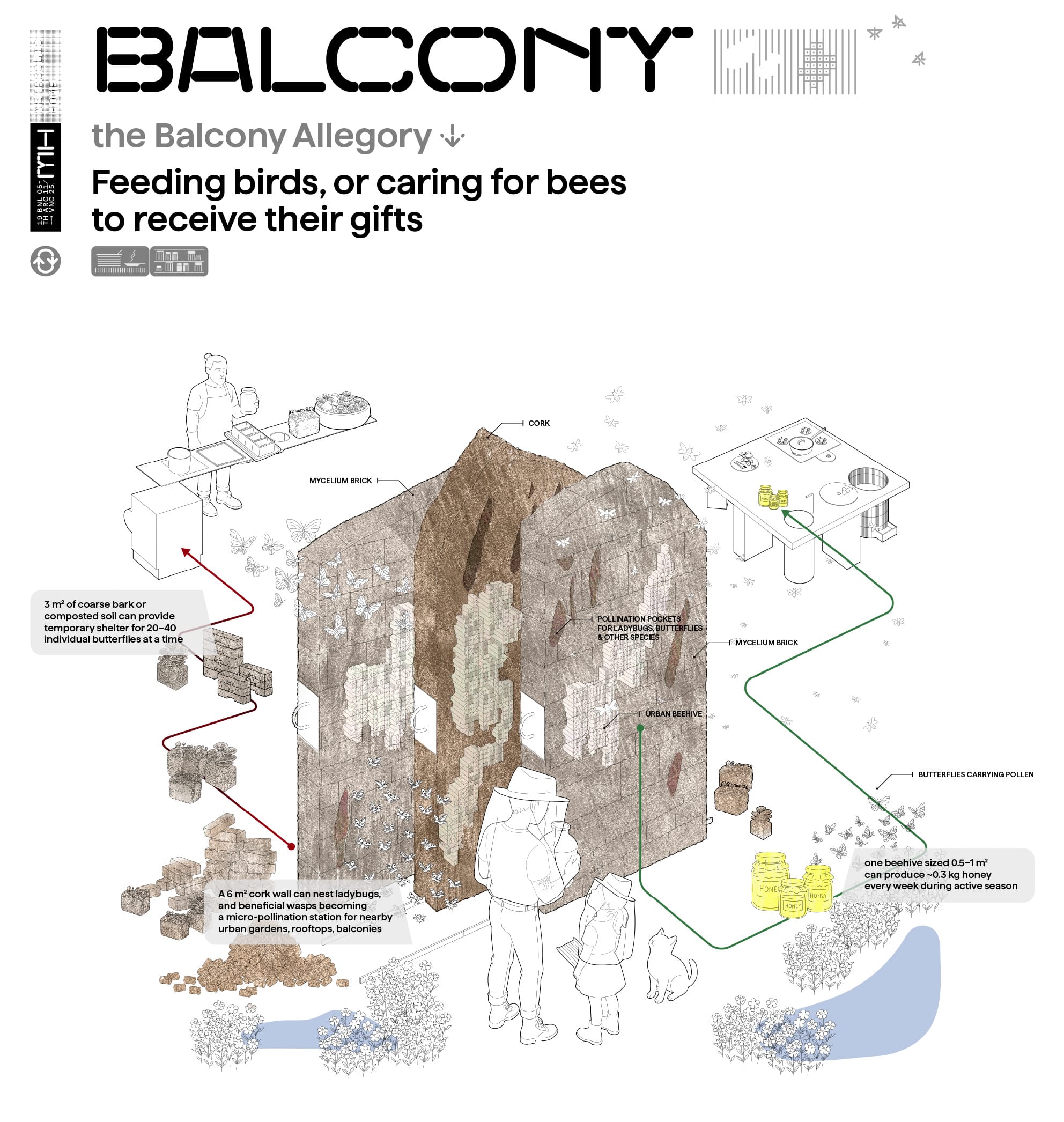

Each space, distinct in function, receives the output of another: food scraps from the kitchen are converted into biochar bricks used in the home elsewhere. Wastewater sustains hydroponic growth on the balcony. The toilet generates antiseptic films. Moisture from laundry is channeled into a shaft lined with mycelium. Objects are produced from byproducts. The logics of waste and reuse are tightly drawn, each component material responsive.

These interdependencies unfold as a series of spatial allegories. Each room stages a condition of transformation sedimented in matter and action. Allegory, here, contains no moral, but emerges through spatial organisation and reorganisation: in the kitchen, one cooks homegrown mushrooms over biochar bricks and compost tanks; in the bedroom, one rests softly over the roots of their garden; on the balcony, one feeds birds and keeps bees. The architecture does not merely describe these transmutations—it enacts them. Architecture emerges as a proposition of symbiotic habitation, a metabolic act.

Human figures appear in ghostlike projections moving through the grid at one-to-one scale, performing gestures. Rather than dramatising this 1:5 model, their presence reintroduces temporality without narrative, inhabiting the installation distantly. The home becomes a stage where narratives unfold without climax or resolution—a recursive process of input, conversion, and redistribution, exposed in its technical and spatial detail.

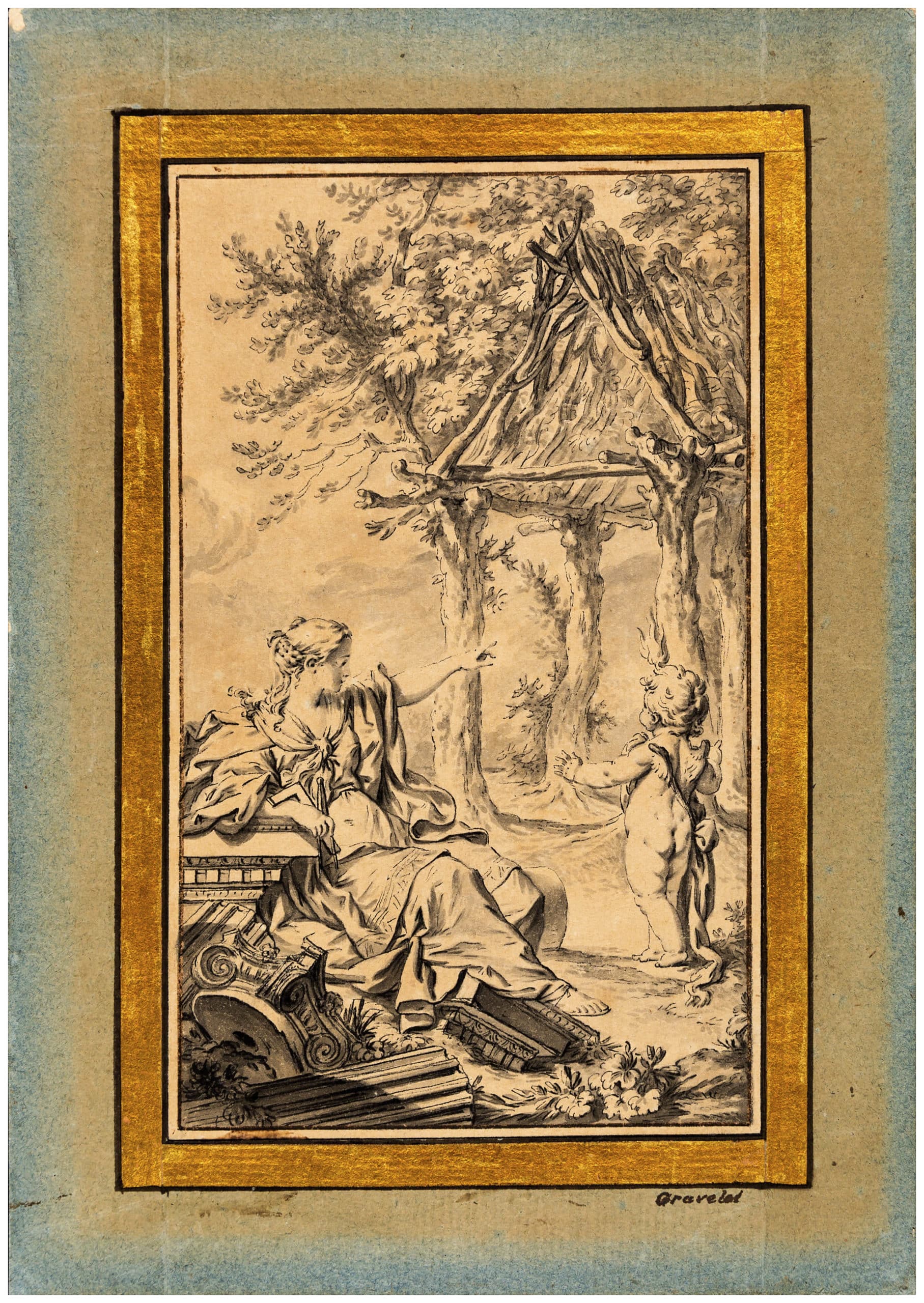

The Metabolic Home enters a dialogue with other allegories of architecture. The primitive hut—whether Laugier’s or others’—persists as a fiction of architecture as nature’s artifice. In Charles Eisen’s frontispiece to Laugier’s 1755 edition of Essai sur l’architecture, a young woman reclines in a clearing before the frame of a hut; beneath her is a pile of broken ruins. These ruins interrupt the fable, proposing a counter-image where past, present, and future coincide.

In these layers of time—a site suspended between formation and decay—allegory communicates with sharpness. If the hut gestures toward origination, then the ruins re-originate that impulse, folding it back in time. Kallipoliti and Markopoulou stage something neither primitive nor nostalgic. It is contemporary and composed, holding within it an awareness of architecture’s sedimentation, of residue that builds meaning through time.

In The Metabolic Home, cohabitation is enacted through a dense choreography of interdependencies—material, performative, and temporal. Bodies, machines, spores, furniture, fluids, and airflows are spatially entangled. Each system receives the trace of another. Each room shelters a metabolic cycle continuing elsewhere. This logic of incomplete, recursive exchange becomes the ground on which the project’s deeper claim rests: allegory is procedural. Like the ruins in Eisen’s engraving, the systems within The Metabolic Home persist in a state of layered entropy.

Walter Benjamin once observed that ‘allegories are, in the realm of thought, what ruins are in the realm of things’.[2] Each allegorical room in The Metabolic Home is a stage for rethinking domestic life: cooking homegrown mushrooms, making kombucha, cultivating a garden beneath your bed, and caring for other creatures. These rituals surrender the fate of their materials to decay, only to reconstruct them within a unique vision of dwelling.

Notes

- Reyner Banham, ‘A Home is Not a House’, in Art in America, vol. 2 (1965), 70-79 (70).

- Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama, trans. by John Osborne (London: Verso, 1977 [1925]), 178.

Paul Mosley is a writer, designer, and educator in Ohio.