Objects That Meet

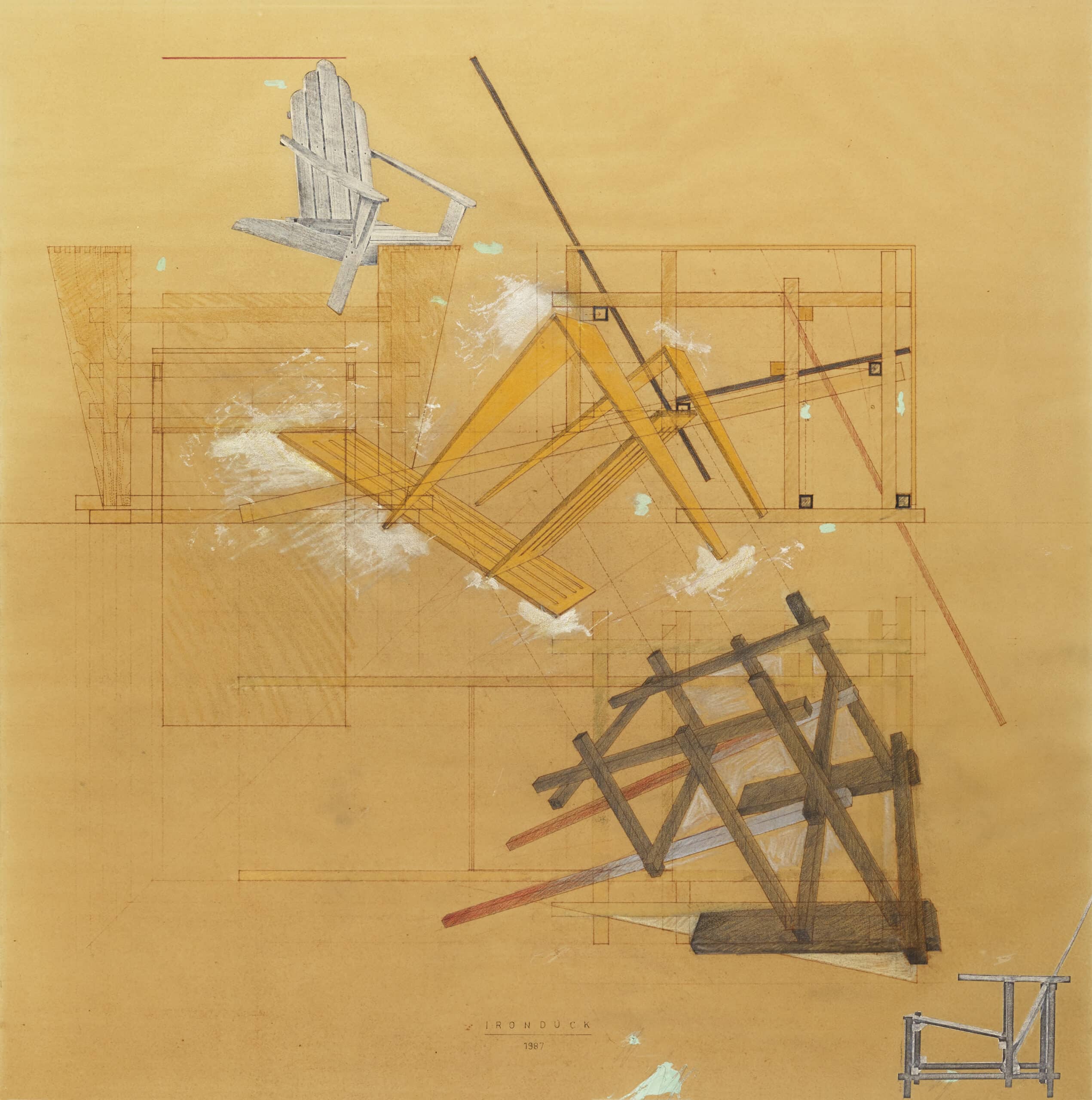

Revered objects that move about in design circles and are found in publications, museums, and galleries earn their status through persistence over time. Take two famous chairs, Gerrit Rietveld’s Red Blue chair of 1918–23 and Thomas Lee’s Adirondack chair of 1903. All chairs have met just by being chairs, but these two meet more intimately and more frequently through a complex mixture of popular demand and curatorial decision. They meet not the way that people do, not because of social arrangement or circumstance, but in kinship. Here with us they meet in affinity – in form and fame. Formally, both are constructed of discrete wooden elements that, when assembled, make distinct figurative constructions. Put side by side and under persistent scrutiny, they appear separated only by degrees, provoking double reading and instability. And only now do both reveal a direct kinship with bridges – networks of wooden elements seemingly held together by will rather than mechanical fasteners and threatening to disassemble and reappear as new figures at any provocation.

Although the three constructions belong in different worlds (museums, front porches, and landscapes), their elemental closeness brings them together – as if they were originally conceived in the same universe, in a genetic workshop guided by similar biology. Elemental, painted, not quite synthetic, they are in their assembled nature suggestively kinetic – movable, fickle, and inconstant.

Handiness separates such itinerant things from other assemblages such as buildings – cast stiff in lengths, heights, and surfaces. Both the fixed and the peripatetic worlds have their voices, talking among themselves, heard by no one except themselves. Well, that is not quite true; although the voices are embedded – frozen, sure – they can be seen and simultaneously felt. Eyes, hands, and tools know those silent voices well, wandering across legs, backs, seats, and eventually figures. Objects made of a dazzling number of woods, metals, and plastics, many of them memorable, some forgettable. And there are dialects. A Tallboy does not speak Chair, a Sofa does not speak Bed, yet they have carrying and movable corporality in common – the bridge and the bed. This liveliness is of course mere history. Today, meuble is just a word in a language, no longer fitting, since such utilitarian things are not in frequent motion but rather frozen-in-place. [1] The dead weight of the well-heeled class. No longer moving – just occasionally moved. The two chairs that meet here do so in defiance of the static, to prompt again the nomadic. To unfreeze the frozen.

Displaced, the human body on the dissection table in the anatomical theatre, is replaced by two chairs, both with distinct but similar anatomies. Two stick figures, side by side, stand on the marble slab in my imaginary theatre. The plot is an exercise in aesthetics, in the ancient sense: how one object impinges on another. In this case, it is the aesthetics of ‘interchairness’ – the deliberate engagement of two objects with each other.

On a spectrum of respectability, indeed of class, the first of the two, Gerrit Rietveld’s Red Blue chair, sits undisputed at the top, while Lee’s Adirondack chair occupies a much lower rung – although still a highly respectable position, particularly in the eyes of connoisseurs. Lifted out of this spectrum and off the floor, placed on the imaginary marble slab and put under dissection – under reduction to non-reducible complexity – a wild but democratic thought appears: can we, by using the Disassembler, make a third a chair? Under scrutiny, the chairs speak again. Still just between themselves, but for us to see. Taken apart, the chairs disappear and a narrative is awakened – rudimentary, basic, clumsy, stuttering, yet clear.

The Third Chair

Today, nobody sits on either of the two chairs. The Rietveld is too expensive; the Adirondack, a rustic figure, sits abandoned on a porch, bluntly replaced by a softer double in the TV room. The collector donates her Rietveld to the museum while picking up an Adirondack – discarded at the other end of town for a recliner – as a showpiece for the never-used veranda. Lateral mobility. The result is a fractured landscape for the Third Chair – part front porch, part museum pedestal – a new chance of enhanced potency.

With the two chair corpses dismembered – legs on one side, backs on their backs, armrests and their sides, all in a neat matrix. A mating game inspired by Fritz Zwicky commences. When dissecting rocket systems, the Swiss-Bulgarian astronomer ‘invents’ (on paper) the German V2 that at the same time is dropped over London. Zwicky later becomes the director of the Pasadena Jet Propulsion Laboratory. He calls the matrix of interchangeable rocket parts a Zwicky Box. The two chairs, dissected into interchangeable parts, similarly serve as a box of possibility. Despite this design machine we are stuck, for weeks on end. In a move of mild exasperation, we return Red Blue to its former glory and suddenly a reference to Karl Marx comes to the rescue. He is said to have exclaimed, when encountering his philosophical elder, G. W. F. Hegel: ‘I found him standing on his head.’

In 1917, sixty-five years before, Marcel Duchamp uses rotation to upset the art world. Employing a quarter rotation, he presents a urinal at a Society of Independent Artists exhibition; disconnected from the customary plumbing and flat on its back, the porcelain object sits on a pedestal. Now passing as a sculpture named Fountain, signed R. Mutt. In the same year, Duchamp presents a coatrack – also on its back – nailed to the floor at the entry of the Bourgeois Art Gallery in Paris. It is named Trebuchet, or Trap, alternatively referring to a war machine and a chess move. The robust- ness of the coat-hanger-on-the wall is shaken – both its use and its placement in the plan – because just as with furniture everything has its place. Lying there on the floor, the hooks are actual fangs, reminiscent of the toothed chains used in road blocks. This is the peculiar quality of many objects that surround us. Find a new assemblage named Trap, and you’ll be surprised how many willing objects await. The coatrack is particularly effective. Objects shrouded in humour are Duchamp’s legacy. In light of the seriousness of his art and our current predicaments, the seemingly effortless humour he and Beckett supply is fundamental in my project. I see my design studio as a theatre where all talk at the same time. The resulting bedlam when Deleuze and Guattari’s stirrup, Hegel on his head, Duchamp’s Fountain and Trebuchet, and Beckett’s Watt (appearing just below) bounce back and forth between me and my graduate students – I, for one, am in heaven. And objects, large as a house or small as a door handle (Lautréamont’s umbrella and sewing machine), all display a new internal liveliness and the very productive ambiguity characteristic of all designed things.

Promptly, we rotate Red Blue ninety degrees, without its seat and back leaves. The armrests turn into haunches, while the gridwork of black bars forming the infrastructure remains serviceable. Comically, the heroic device sits upside down – looking for its seat. The pale members of the discombobulated Adirondack lie waiting. The dissection has shifted the members from ‘legs,’ ‘seats,’ and ‘backs’ to ‘pieces at hand.’ Inspired by the graphic simplicity of Red Blue’s black seat and back, we begin to notice the parsimony of the sturdy folk object and progressively see the pieces just as building material. After much design iteration (with legs turning into arms, backs into seats, and vice versa), the Third Chair appears like a phoenix. As a synthetic object, both chairs appear inseparable but in parallel. Past purities have disappeared in this fusion, yet the Zwicky Box teases with its promise of other versions of the union of two diverse chairs. This is what happens when we take things apart.

Notes

- Meuble: a piece of furniture in French – here as distinct from the house, which is immovable.

Excerpted from Lars Lerup, The Life and Death of Objects: Autobiography of a Design Project (2022), published by Birkhäuser. Copies of the book can be purchased here.