Drawing Out Gehry

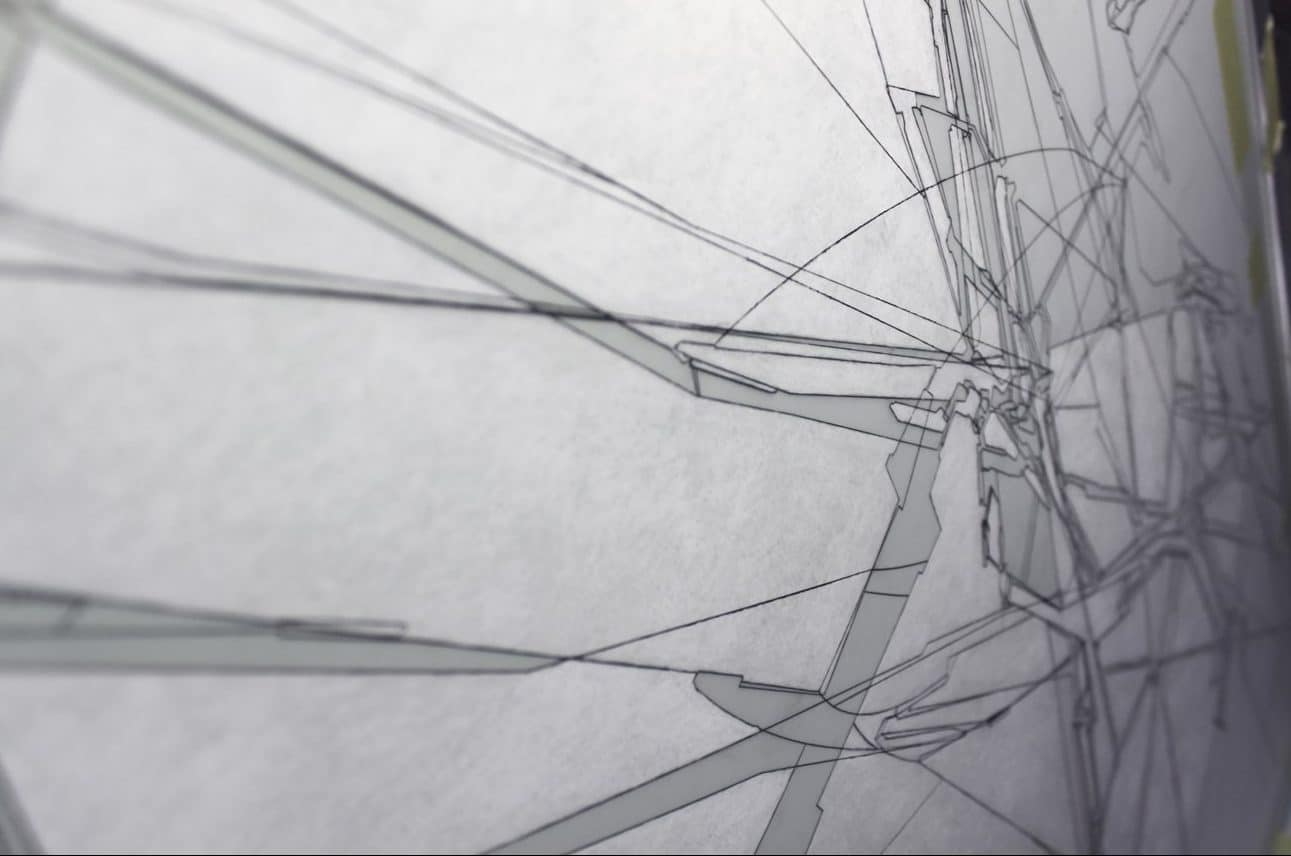

There is something about the immediacy of drawing at a large size, standing in front of a drawing board that brings the quality and urgency of instant involvement with a subject in view.

Drawing at a size in relation to your body allows for the drawing not to become object, treasured in hand, at arm’s length. Rather, the direct relationship with a subject extrapolated through drawing processes and techniques brings this subject closer; it makes it somehow tangible, capable of being experienced and touched.

I use drawing to observe situations and generate an understanding through drawing.

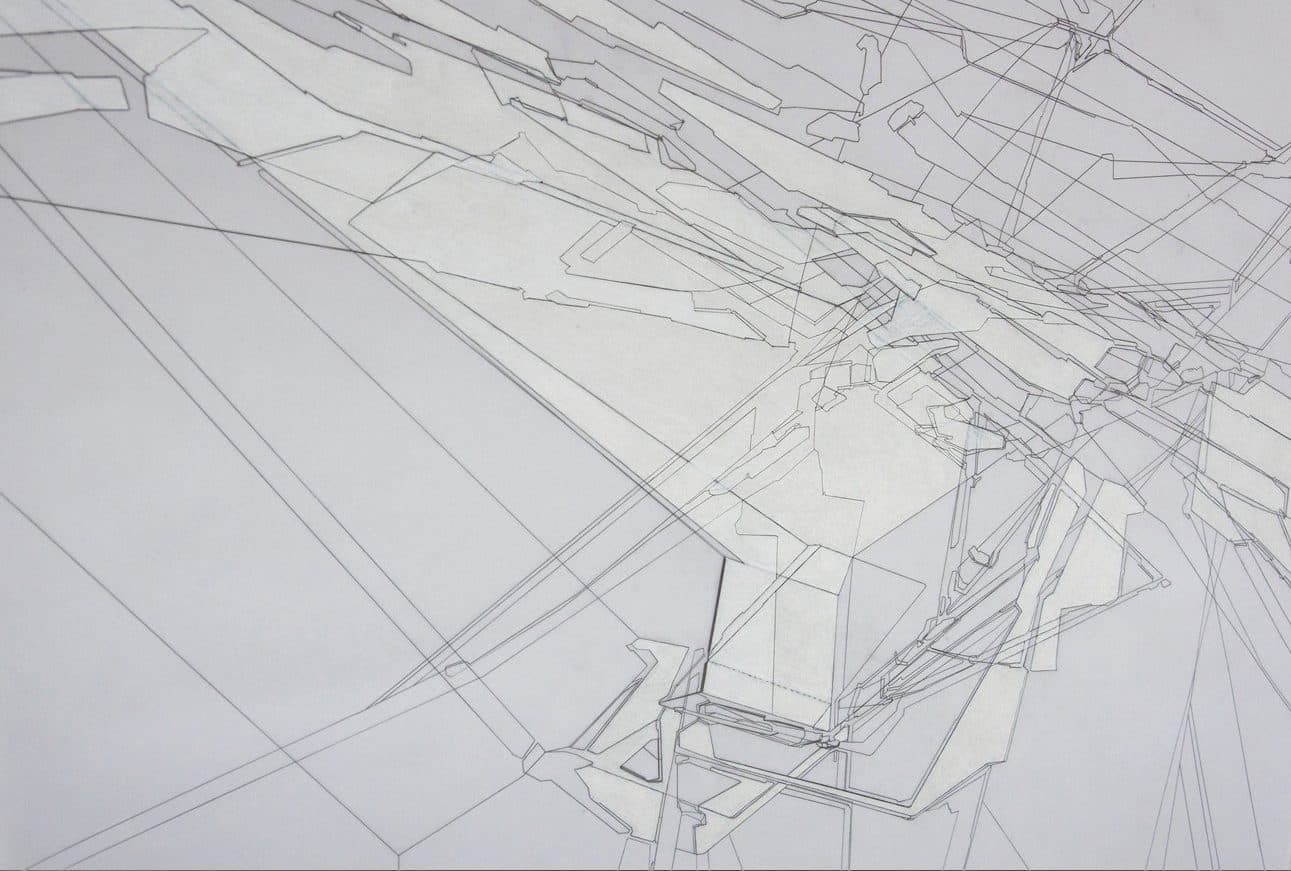

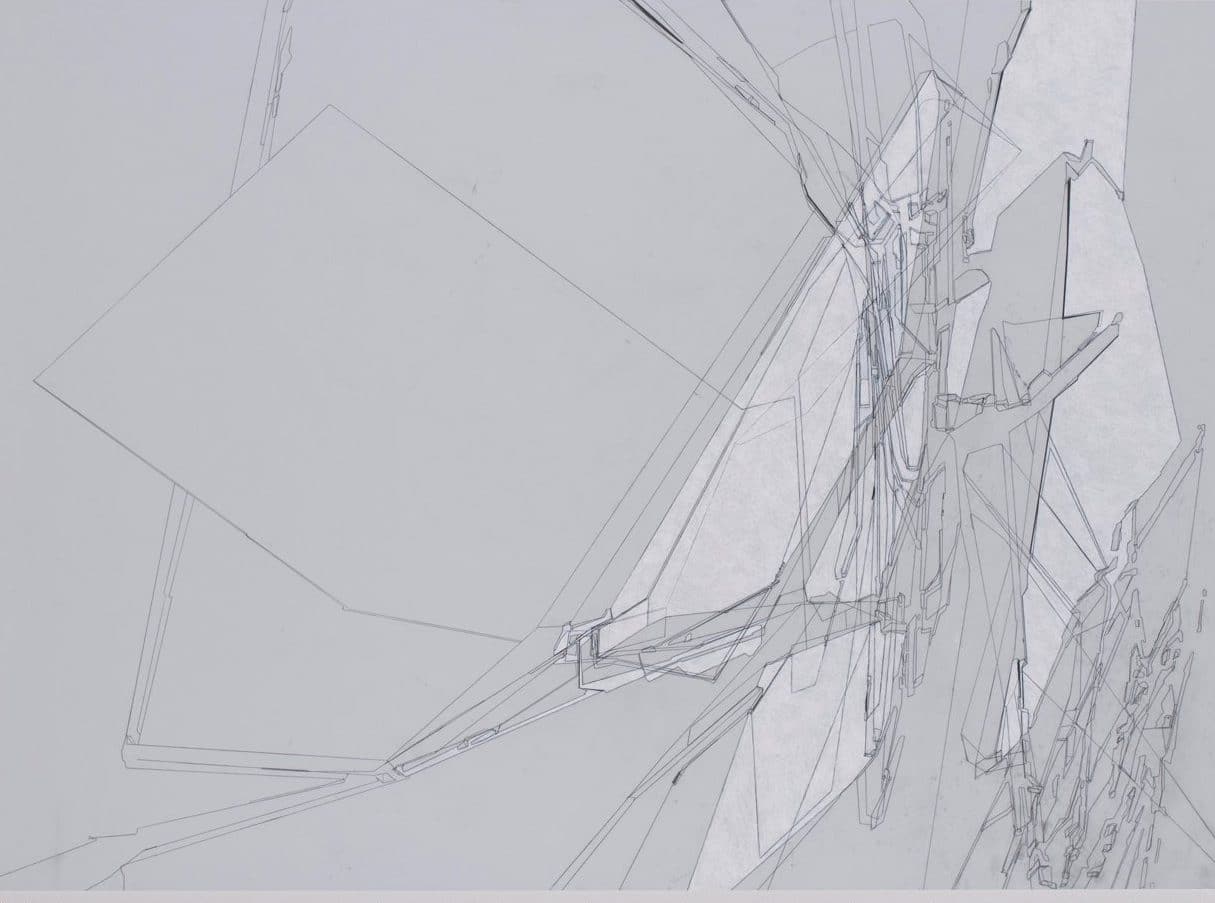

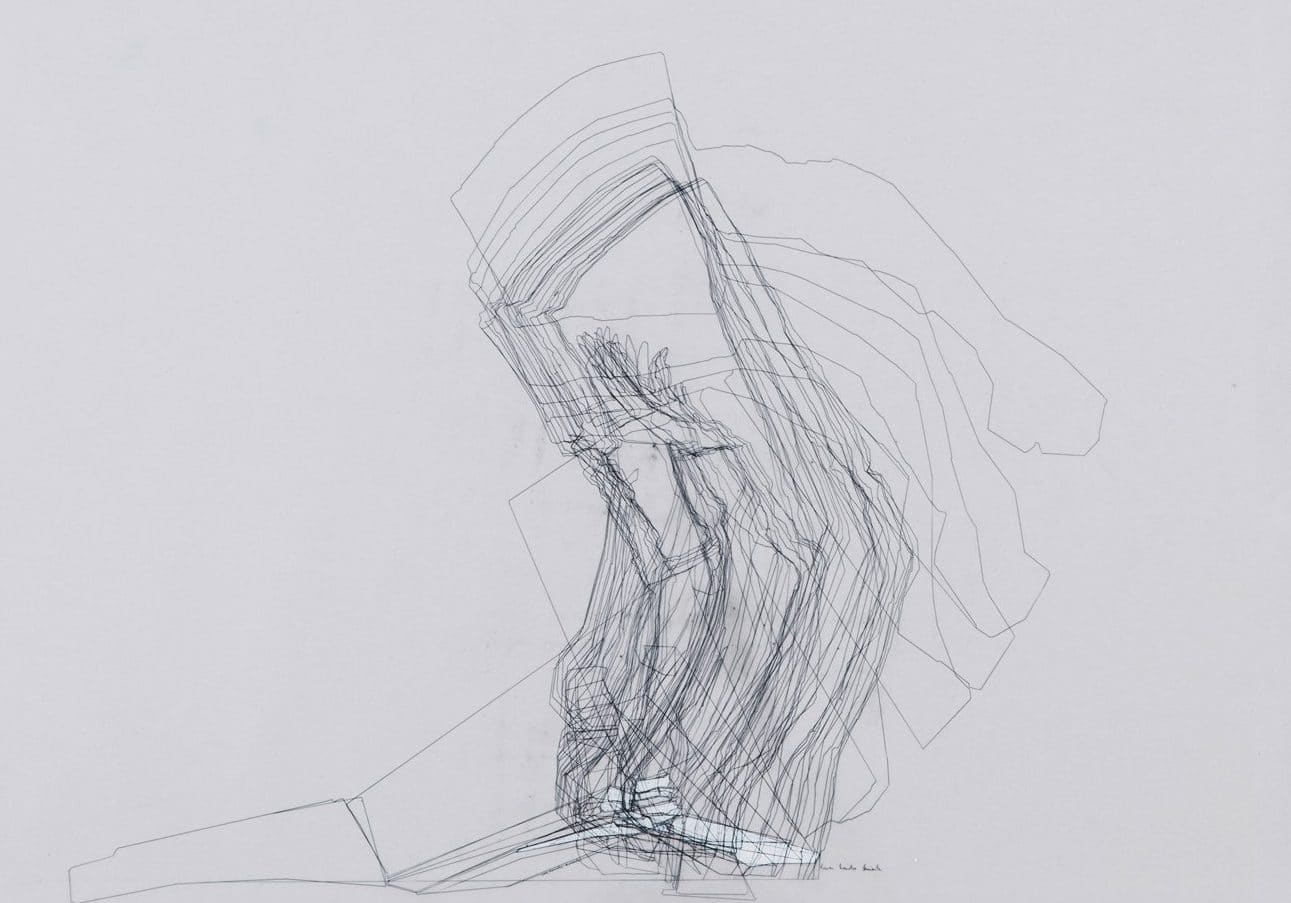

I draw on a situation – tracing off film footage and photography, then using this to extract spatial/architectonic content – until there is an understanding of the the formal content at hand. This process of drawing on the subject and tracing aspects of it, is done by drawing iterative points of view of the subject and iterative points of view of the subsequent drawings. Every reiterated drawing is a refinement and unraveling of the compressed spatiality present in the subject. I trace and draw in modes of observation and speculation until I reach a turning point – a poiesis – where the drawing leaves its status as one thing (its representational role) to become something else. At that particular moment in the process, I can draw through the situation I am looking at. What is to be seen in the drawing is no longer visually representational of its source material, but is a mediation of inherent and observed architectonic intent.

In Drawing Out Gehry I observe a sketch of Frank Gehry’s Goldwyn-Hollywood Library. My interest in Gehry’s drawing is two-fold: drawing in its representation role, as it is made in the service of a building practice, leading up to the construction of the library; and drawing used as a tool for reflection.

Gehry’s hand seems to drift intuitively over the paper, not sketching exact architectural form or details but rather in search of the architectural capacity of what has been designed. It is this duality between representation and reflection that interests me. With this idea as a starting point I begin a drawn dialogue with the sketch: I observe and speculate on the spatial layers embedded in the sketch and begin to extract spatial/architectonic information.

As representation branches into autonomous drawings through a sensing line, an awareness implicit to the observed complexities is obtained – a mode of drawing that dwells in-between observation, responsiveness and speculation.

Here, drawing as a practice, is based on a simultaneous performance: every line engages with the delineation of architectonic qualities of the observed and the expression of more elusive qualities – rhythm, proximity, the proportion of solid and void, line resolution and thickness, absence and presence of scale – contributing to the architectonic expression of the drawing.

It is an utterance of the world, a viewing of the world with the immanent collapse of an object-subject viewpoint and in which the world of objects is replaced by a world of events.

What does it entail – this manoeuvring between the figurative and the figural, between object and the event it stages, between measurability and the subject’s perspective, urging multiple points of view poised by repetition and iteration that implies constant time-related change?

It is the pleasure of architecture that lays in the discovery of compressed spatiality as one draws through its representations. What a delight it is to stand at the drawing board, being kept at arms length from entering the drawing, attempting to capture architecture without being an illustration of it.