Ritual and Repitition at San Cataldo Cemetery

In an AA article from 1995, Adam Caruso wrote that ‘buildings are about many things. Their design develops out of a set of complex and changing circumstances and, once built, the ‘meaning’ of a good building can shift and remain relevant as its social and physical situation changes.’ The same can be said of a good drawing or set of drawings. In the case of Aldo Rossi, nowhere is this more apparent than in the series of drawings produced between 1979 and 1981 for the San Cataldo Cemetery in Modena, Italy.

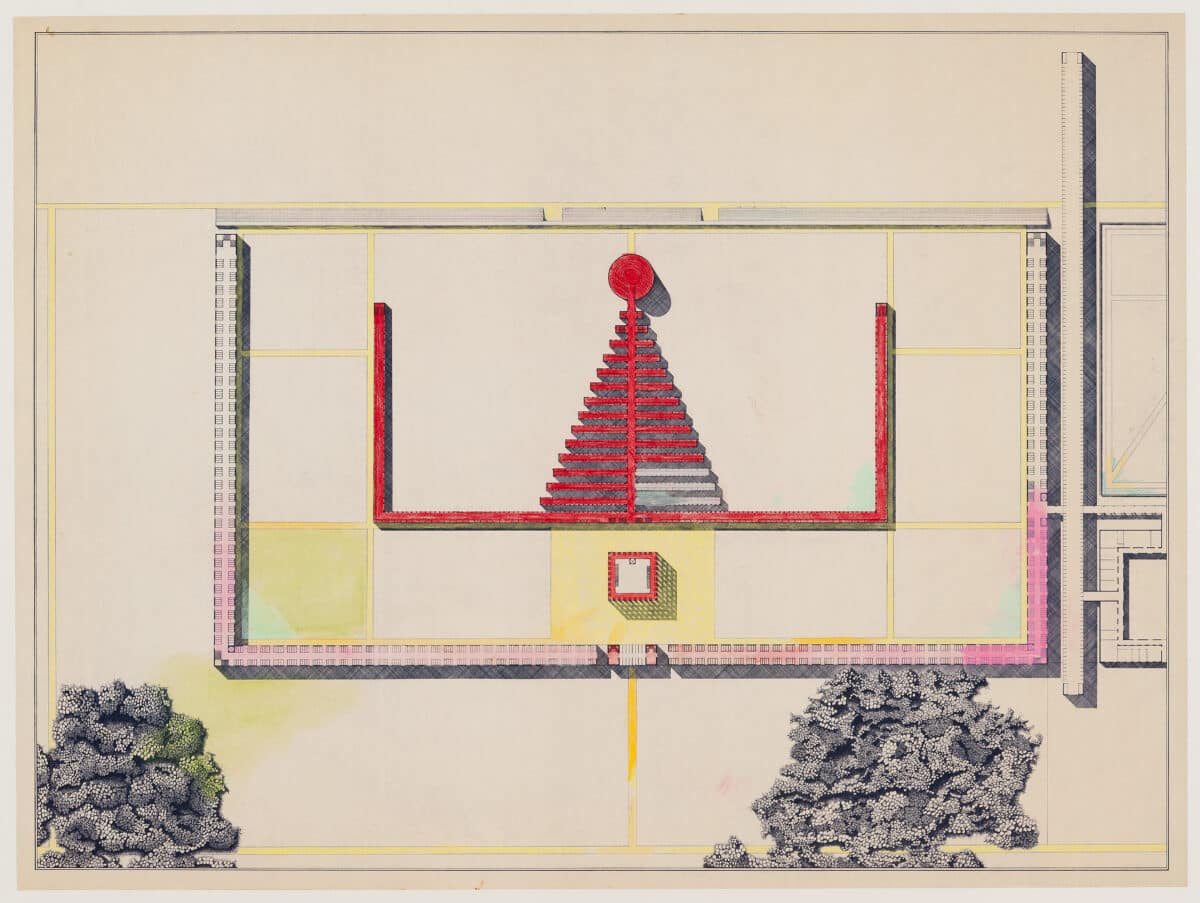

One of the earliest drawings in this period, ‘Presentation Drawing’, introduces three central characters to Rossi’s narrative; the Circle, the Triangle and the Square. These represent the communal grave, the Columbaria, and the Ossuary respectively. There is an element of classicism in how the restrained forms are composed and centred within the rectangular enclosure. Red highlights their significance, while the rest of the drawing is largely black and white.

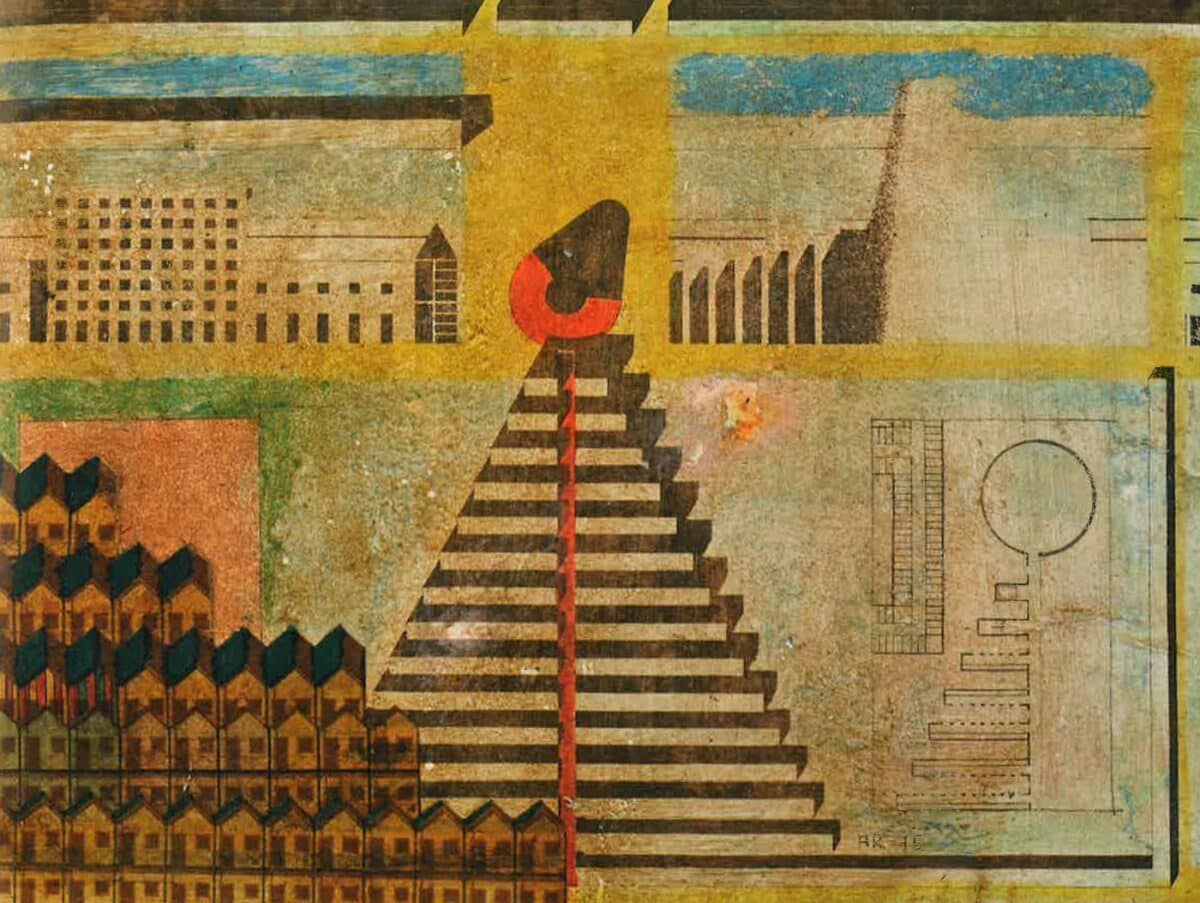

Subsequent iterations of this drawing explore these forms further. In ‘Untitled’ we see the triangular form exaggerated to take centre stage, further emphasised by the use of shadow (see here: . To the bottom left, rows of houses appear to rise and stagger in competition with the scale of the Columbaria. These hint at an association between everyday domesticity and the monumentality of the cemetery. At first, they appear to be repeated randomly, but on closer inspection, a careful alignment to the central axis of the circle is revealed. The repetitive, almost dogmatic nature of these houses is in contrast to the delicate pencil outline visible on the right. The top portions of the paper are taken up by elevations of the Square and the Cone – now visibly a dome. In contrast to orthogonal modes of representation, there is a cubist attempt to capture the full experience through the use of multiple viewpoints on one sheet.

Rossi’s drawings of the cemetery become increasingly imaginative as it came closer to being built. In ‘Geometry of Venetian Memories’ we see the forms of the cemetery pulled apart and reassembled once again. The Ossuary now shares drawing space with the Teatro del Mundo, Rossi’s contribution to the Venice Biennale in 1980.

Both projects concern themselves with the human condition in different ways. With the cemetery, the perspective is such that we are left at the foot of an altar; with the Theatre, it is more head on. There is a sense of being at the mercy of something at one instant and confronting it in another. The hand of San Carlo adds an otherworldly dimension to the cemetery – the only human representation in the set. The rough vertical line subdividing the canvas seems to suggest a separation between the world of the dead and the theatrical world of the living; a tension between the sacred and the profane. Allocating over half the sheet to the cemetery altar seems to suggest a persuasion towards the former over the latter.

Also apparent is the divorcing of fragments from their real-life context and the re-collaging of these to form a new ensemble. An absence of scale emerges as pieces are drawn ambiguously, looking to be the same size as one another. This distortion reaches a peak in ‘Constructions in the Hills’, where the Circle, Square and Triangle are recomposed once again, this time framed by the skeletal figures of a horse and a crab.

With this final drawing comes the realisation that each iteration reveals information about its predecessor. If we take each drawing as a stage in which, with each act, the familiar characters of the Circle, Square and Triangle are brought out to perform in different ways, we see how the drawings begin to illustrate Rossi’s view of the city. Each building signifies a moment, and it is through the recollaging of these moments or fragments that they become an embodiment of a lived experience. This is not dissimilar to how Rossi described the city in his writings, where he viewed buildings as characters that have their own agency; miniature set pieces that enable the subtleties of everyday life to play out.

Our cities are made up of fragments. It is the layering of these that creates heterogeneity and adds richness to them. And it is this richness that Rossi’s drawings attempt to capture, starting with basic principles and culminating in euphoric rapture. His resistance to homogeneity is the same fight we are battling today when trying to avoid the tabula rasa approach to urban planning that has become our industry standard. An approach that favours wiping everything and starting over with a clean slate in the name of efficiency.

The poetry of these last two drawings in particular is largely derived from the sense of immediacy they achieve. They are primal. They feel free and have a sense of being assembled quickly. The darkness that pervaded the last drawing is now replaced with light as shadows are reduced to bare slithers. The distorted spaces depicted from memory, coupled with the repetition of fragments, bear a resemblance to Giorgio De Chirico’s paintings. They are reflective of the shifting of values that architecture underwent in the late nineteenth century with the advent of modernism.

The presence of opposites such as life and death, shadow and light, and their repetition seem to suggest a cycle of sorts. The Rossian city is cyclical, or rather, made of many cyclical incidents that overlap with one another. Contrast this to the functionalist city which operates like a switch that is either on or off. There are lessons here to be learned with regards to shaping our future cities. The current discussions on the impact of COVID-19 and the technological leaps experienced over the past year on our future public spaces are as inconsequential as the Utopian monologues of the early twentieth century. Whatever projections are made, they will always pale in comparison to the nuances of everyday life. Rossi’s ability to remain faithful to his own convictions is evident in this set of drawings. The formulaic approach to building today has much to learn from his legacy. Rossi’s persistence offers a lesson to architects today who are pressured to respond to a variety of transient trends, that by persevering you can win.

Marwa El Mubark is an architect and founder at avisualcompendium, a platform exploring the rich intersections between art and design through the lens of abstraction and composition.

This text was entered into the 2020 Drawing Matter Writing Prize. Click here to read the winning texts and more writing that was particularly enjoyed by the prize judges.