Roland Simounet: De La Verité en Architecture

For an artist, ‘getting down to work’ is an instinct carried out spontaneously. […] The first outpouring in the pages of the sketchbook, when thought turns into action, at the meeting point between a project and a site, is so strong sometimes, so commanding, that one has the feeling that it cannot be contained and it must overflow from the sheet of paper. The sketchbook page is a moment of immense freedom, of a deep interior silence, a conjunction of intuition, inspiration, and culture, but also childhood memories, an emotion stirred in some other previous place, that is preciously preserved, unspoken, and catches one when least expected.

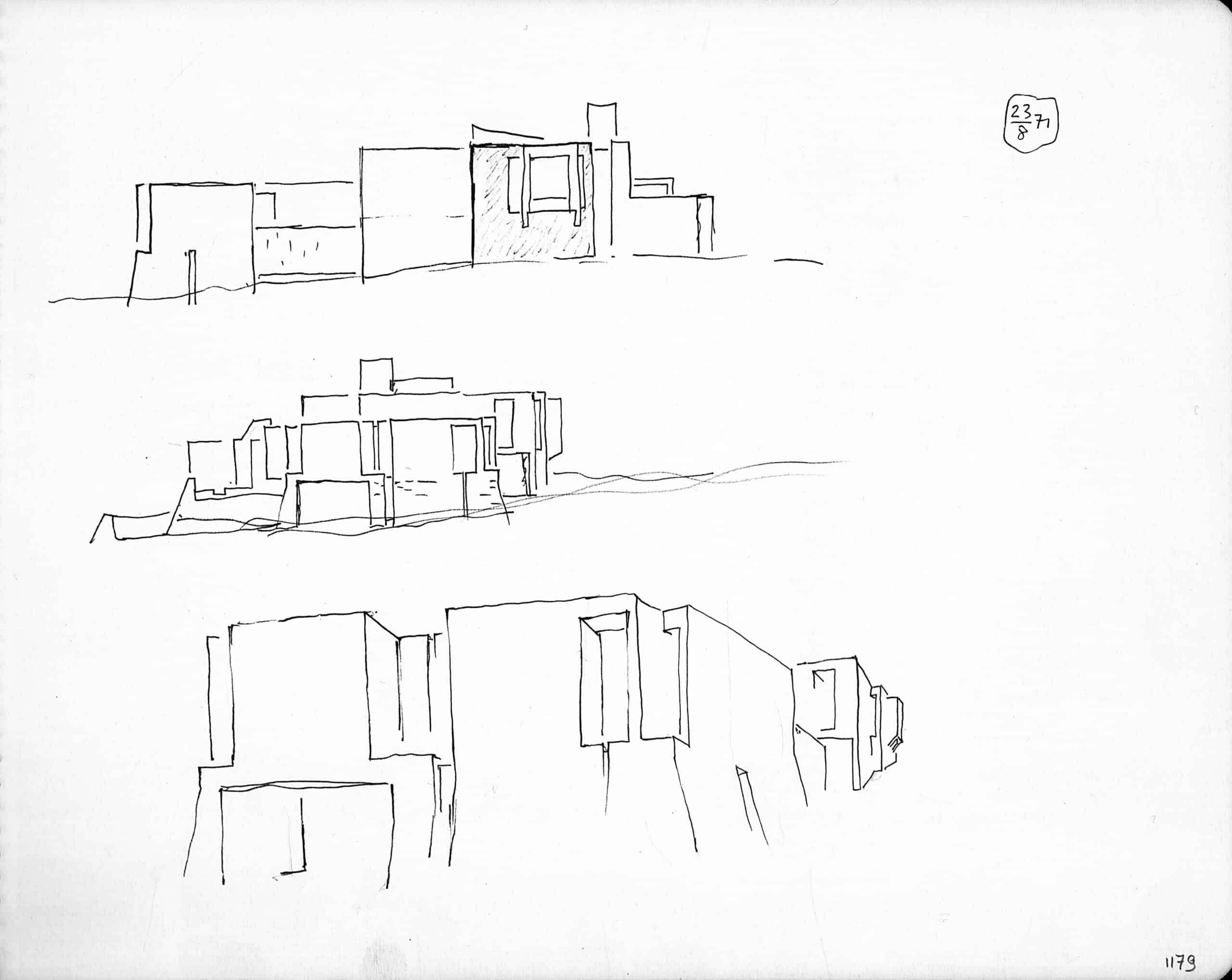

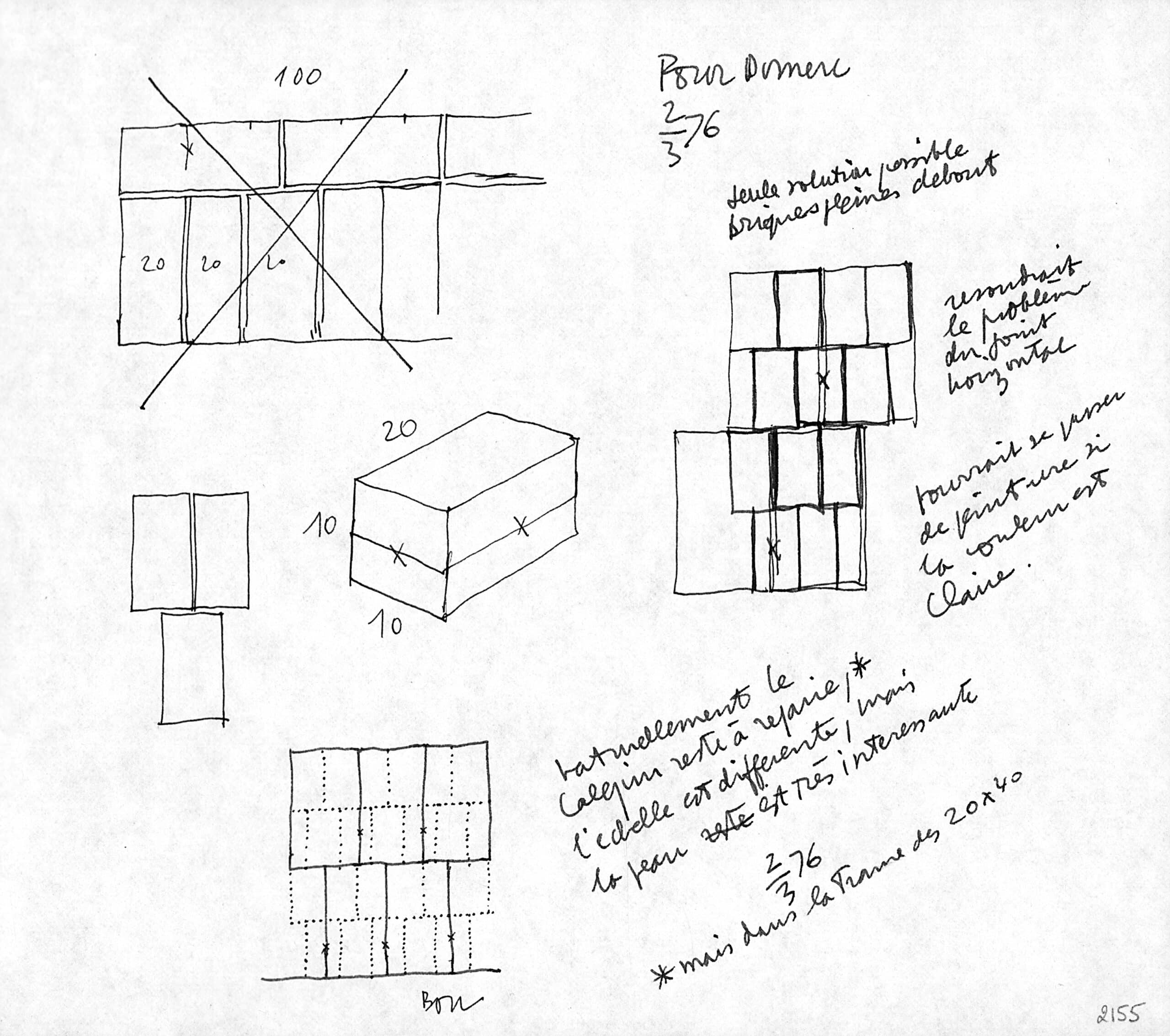

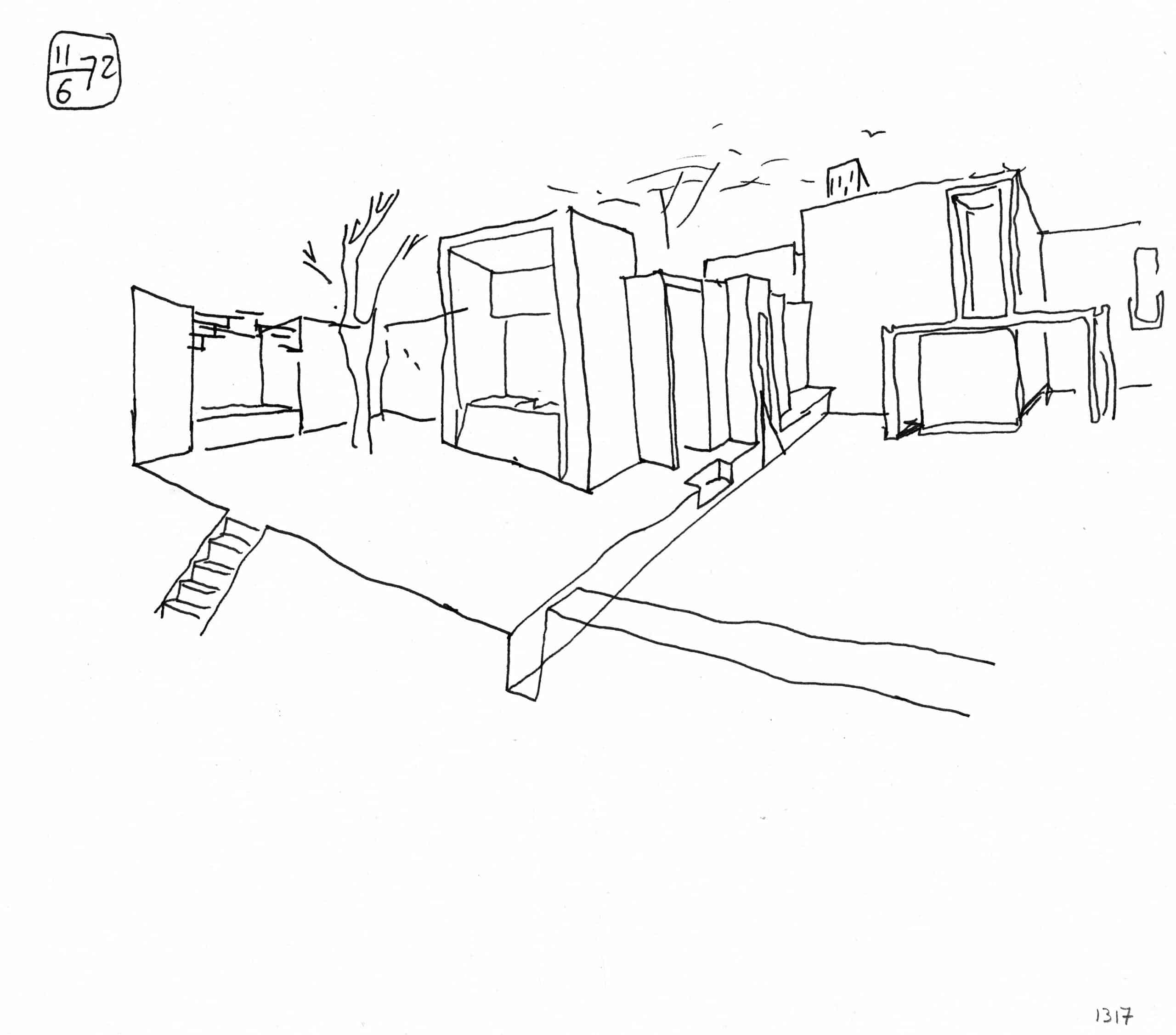

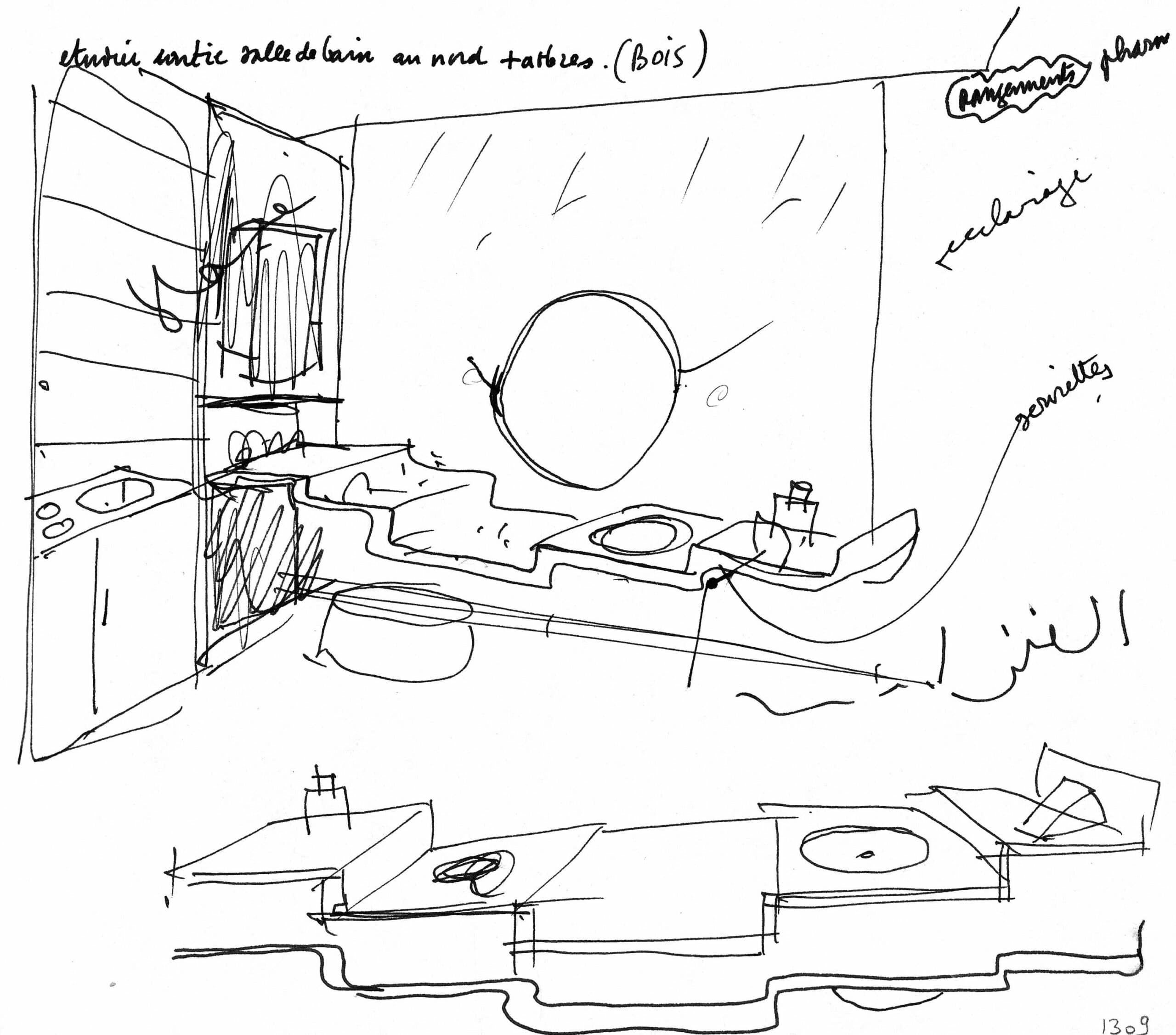

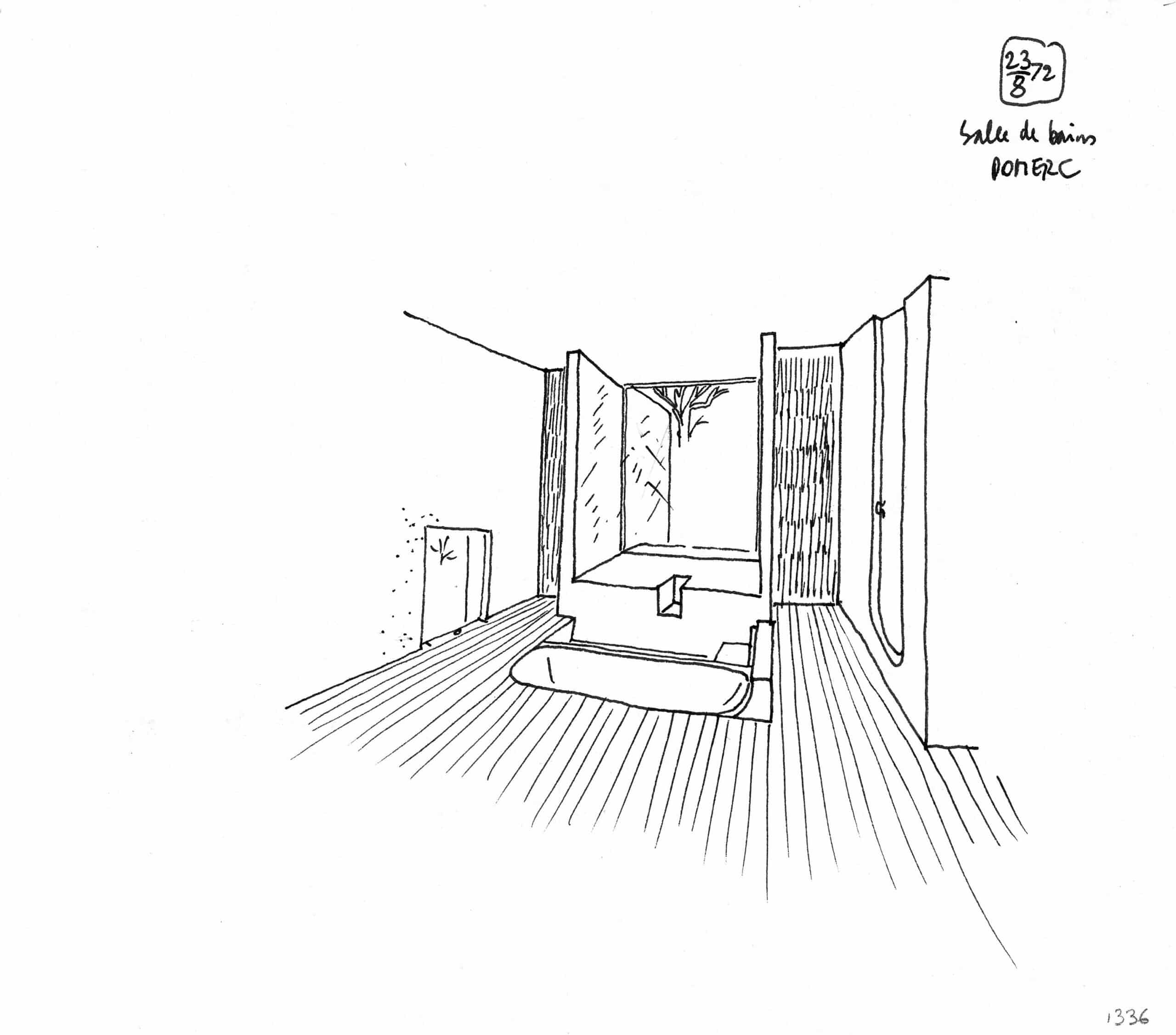

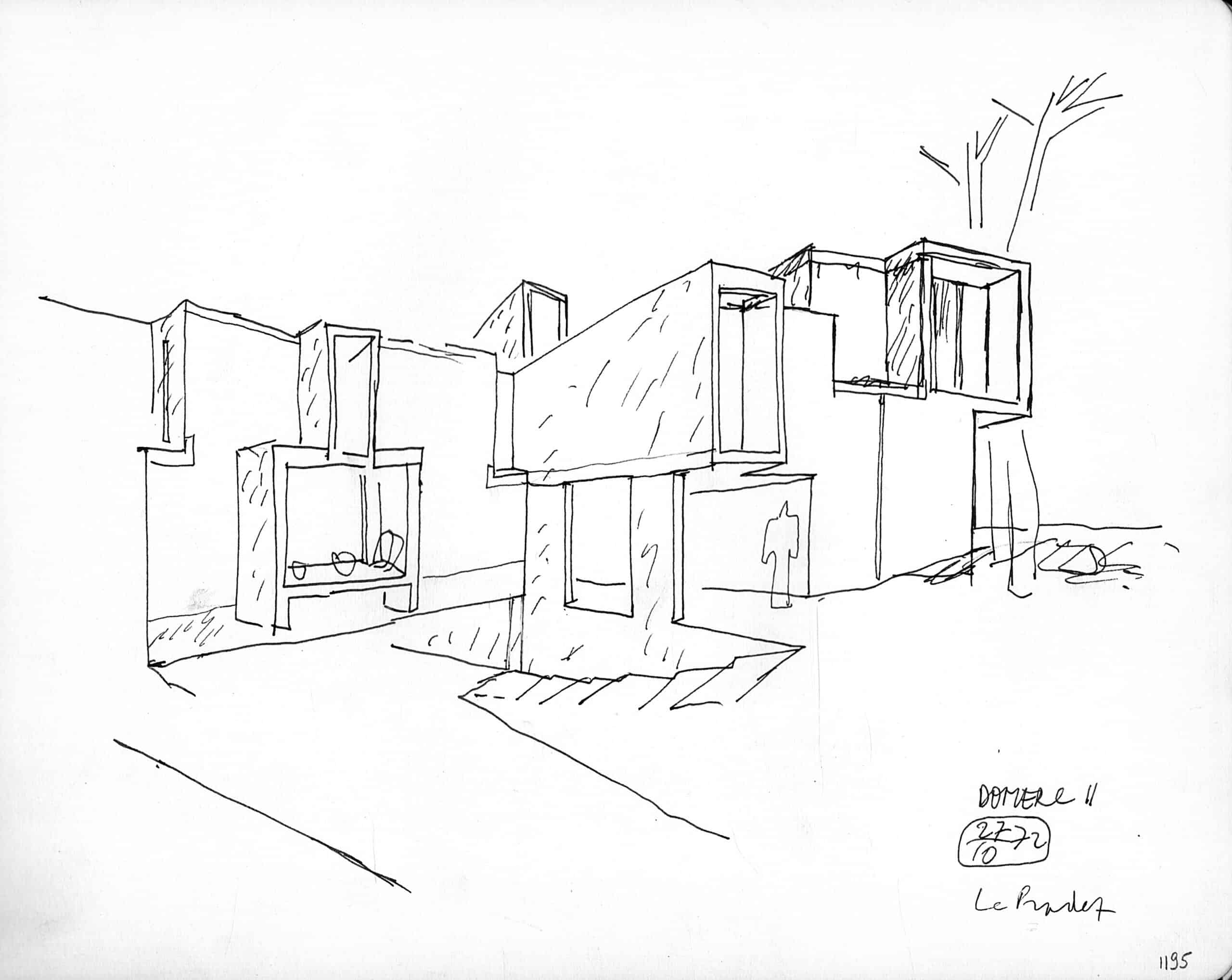

There is this passage of thought through the hand that is drawing and this condensing of the idea, rare, unique, that materialises in a stroke, precise, rigorous, irrefutable. Drawing has this virtue of saying everything, what is, what is not yet, what is in the head, what is in the hand. I have heard and even read some absurdities saying that to draw, for an architect, is to inhibit thought! The sketchbooks of Roland Simounet are outstanding proof to the contrary. We see the project being born through the pen, and the pen follow the project to its final outcome. From a distant hillside planted with a stand of trees down to the detail of a staircase, from the imposing mass of the apartment block down to the arrangement of the bricks of which it is constructed.

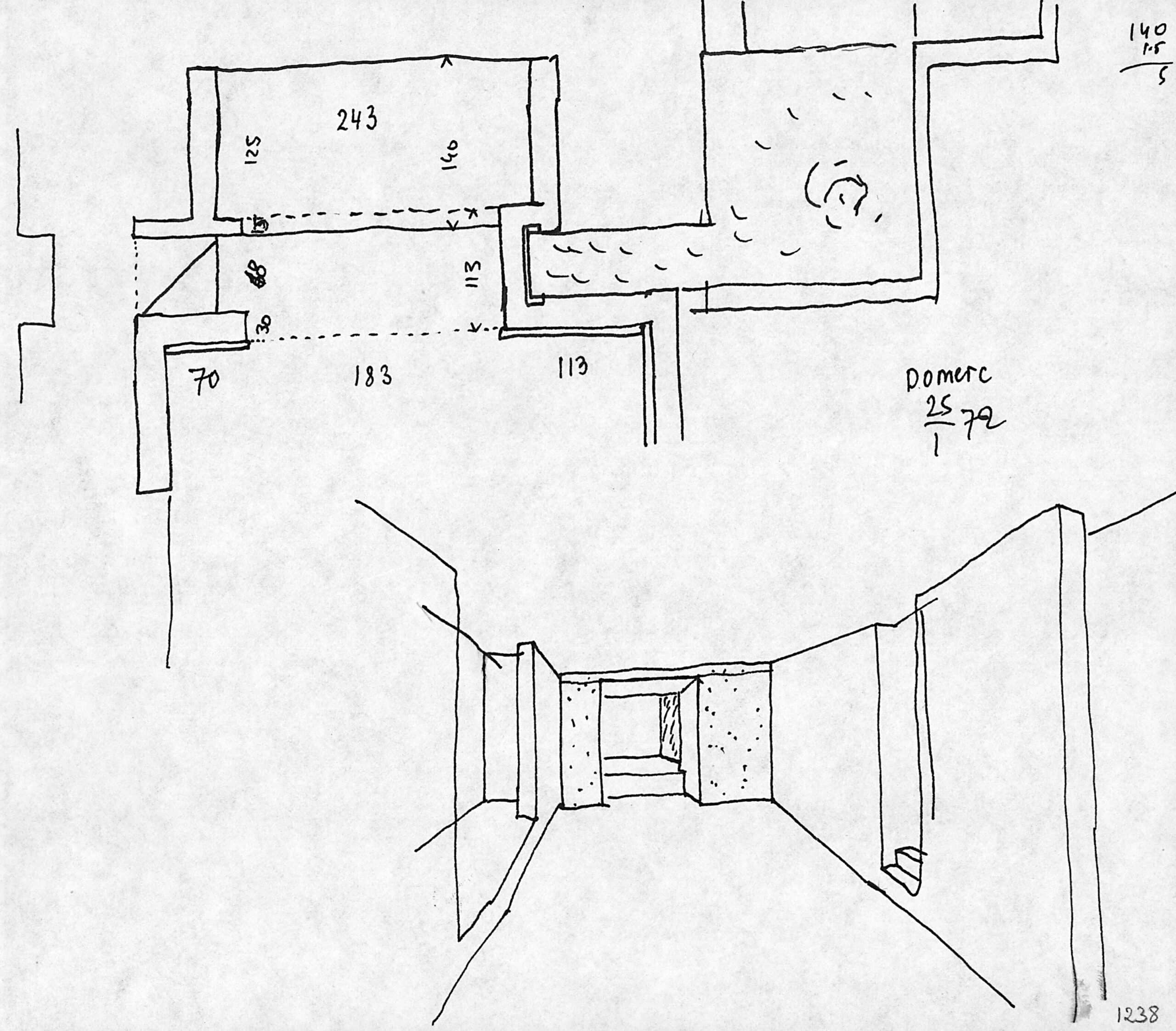

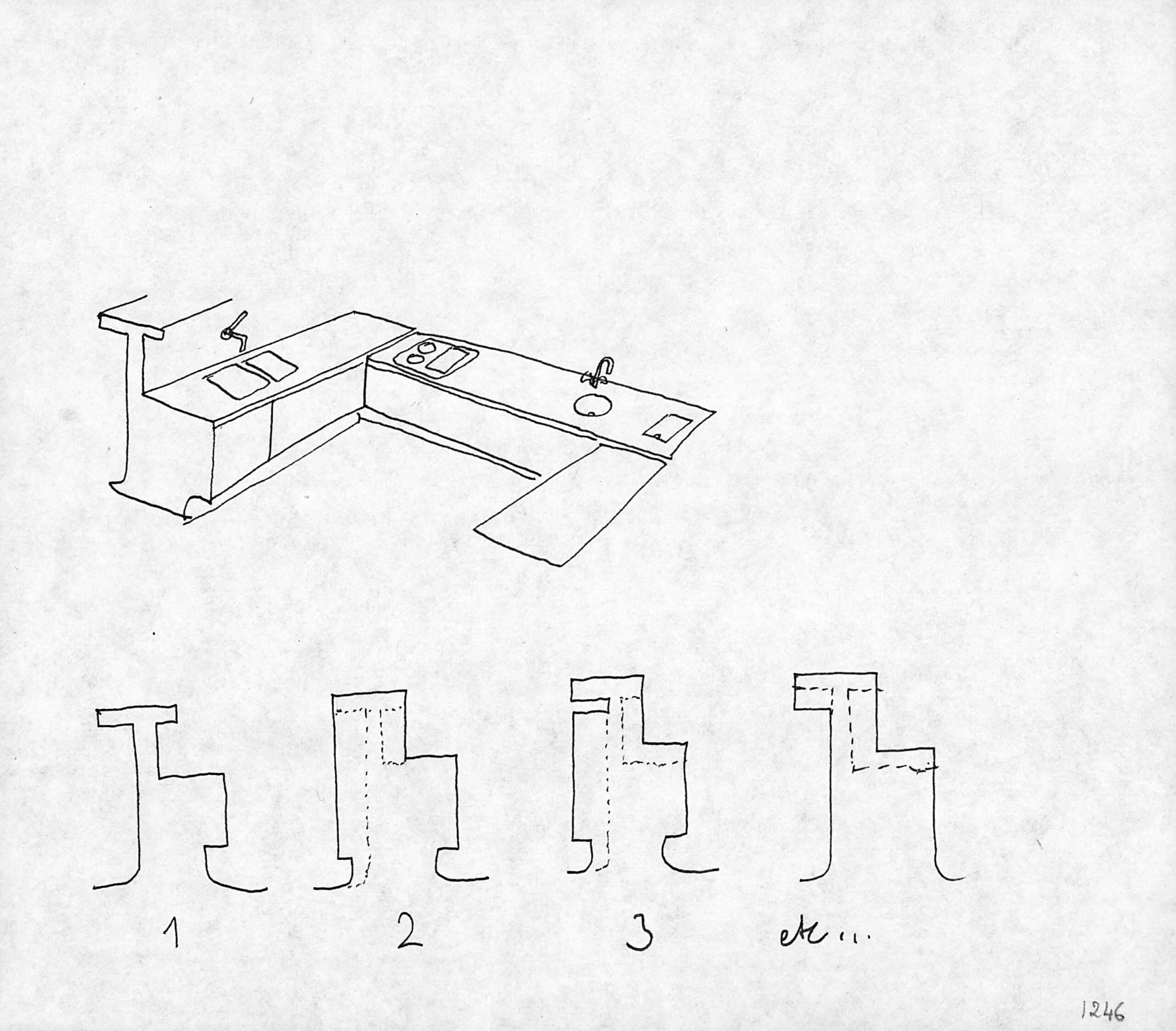

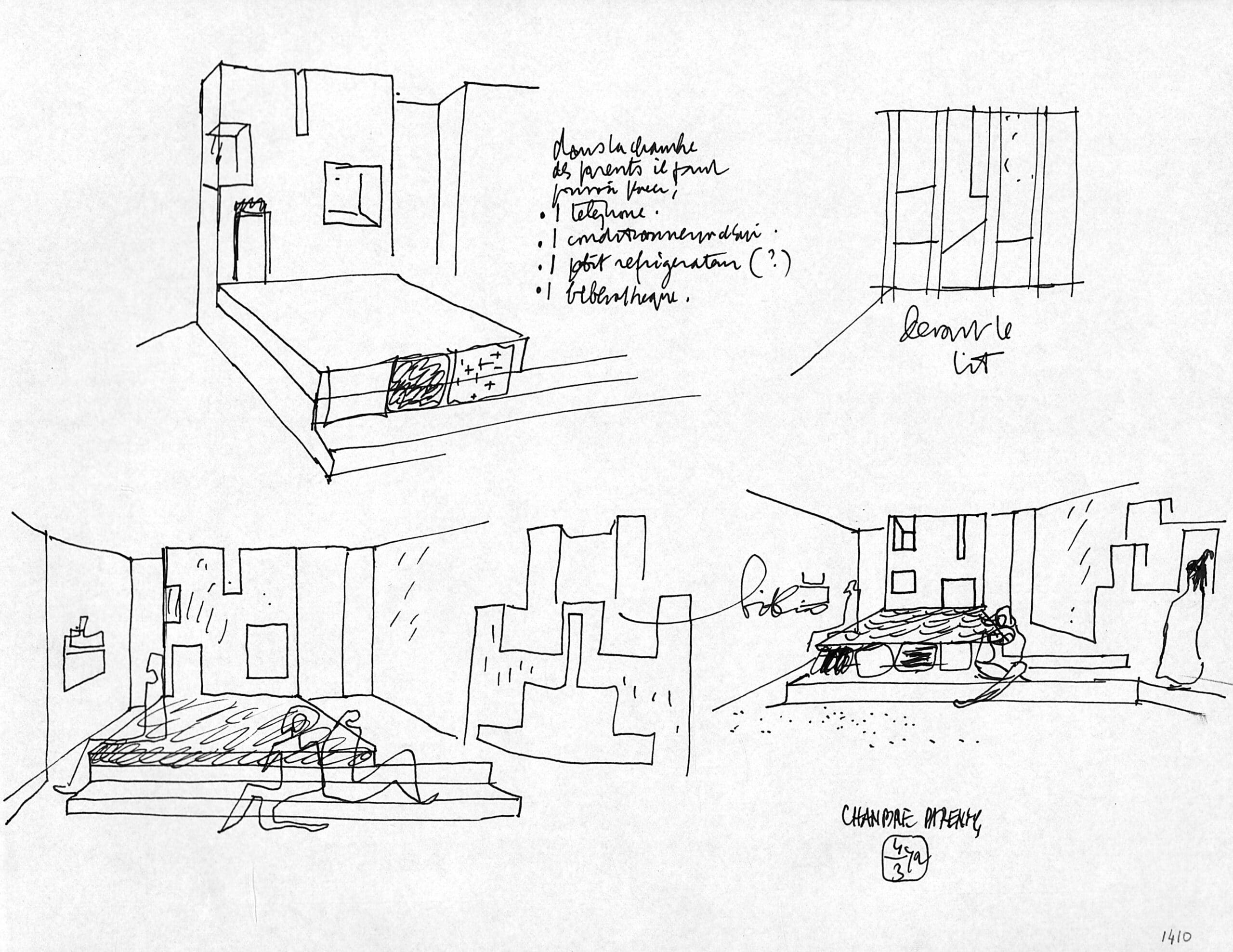

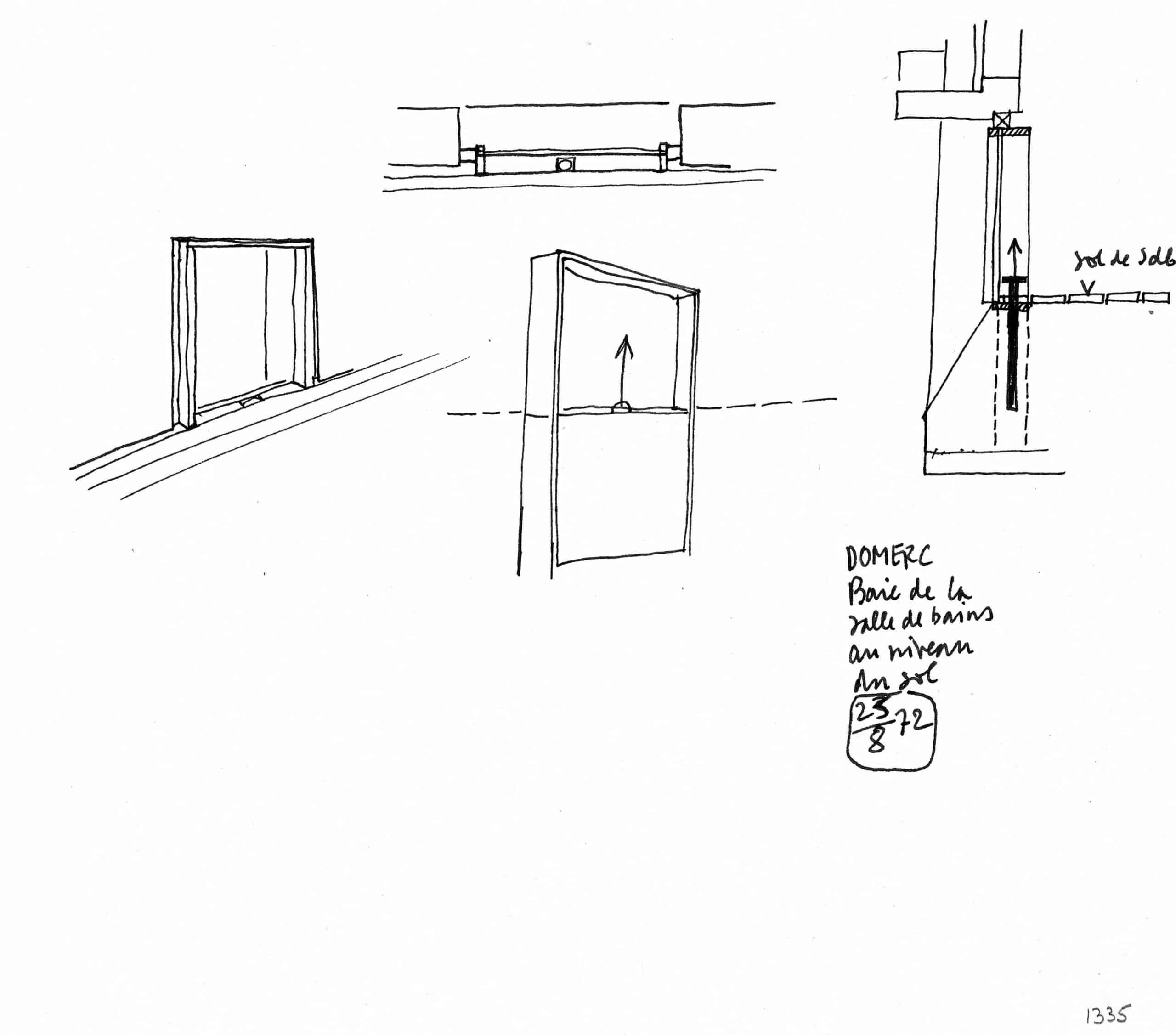

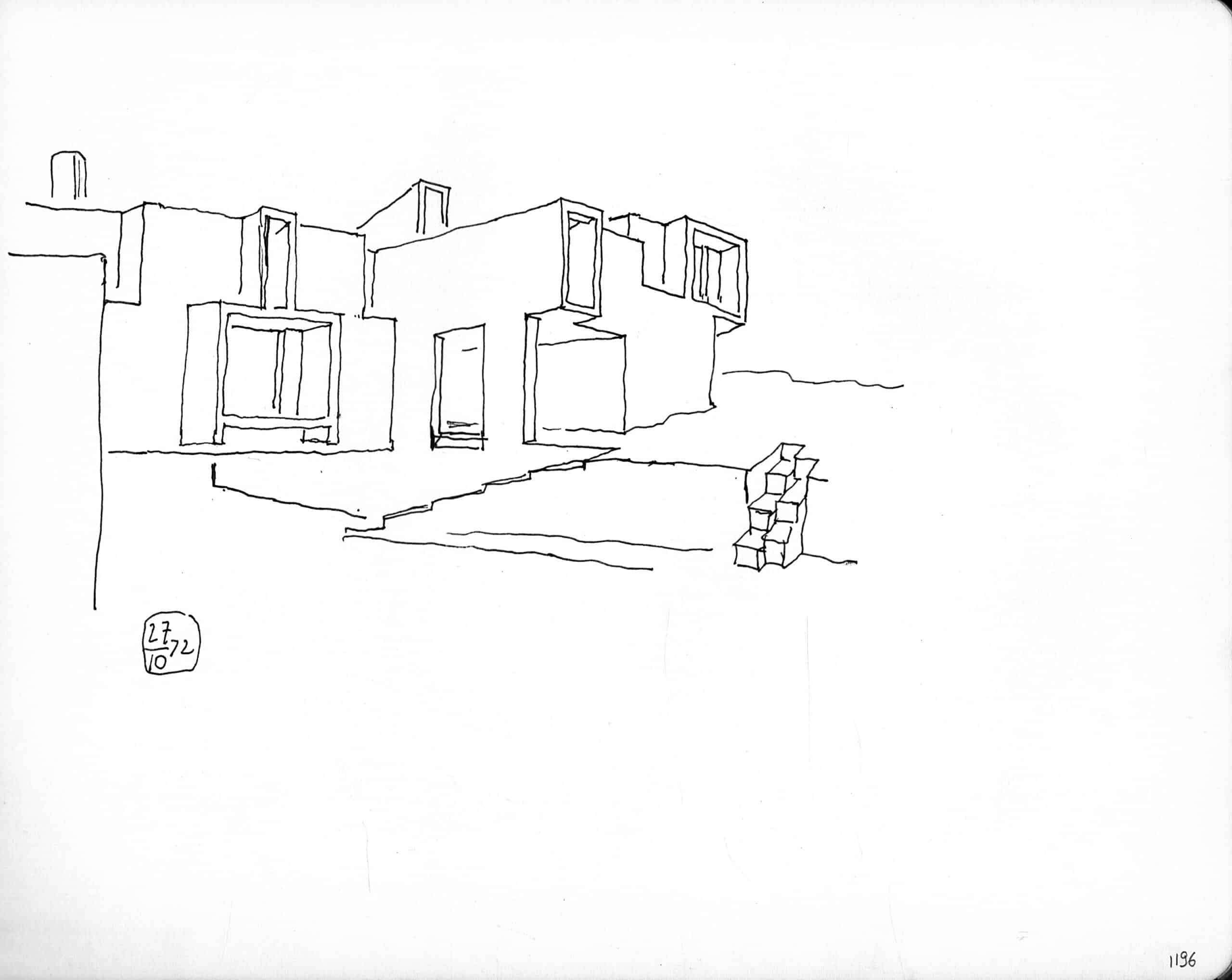

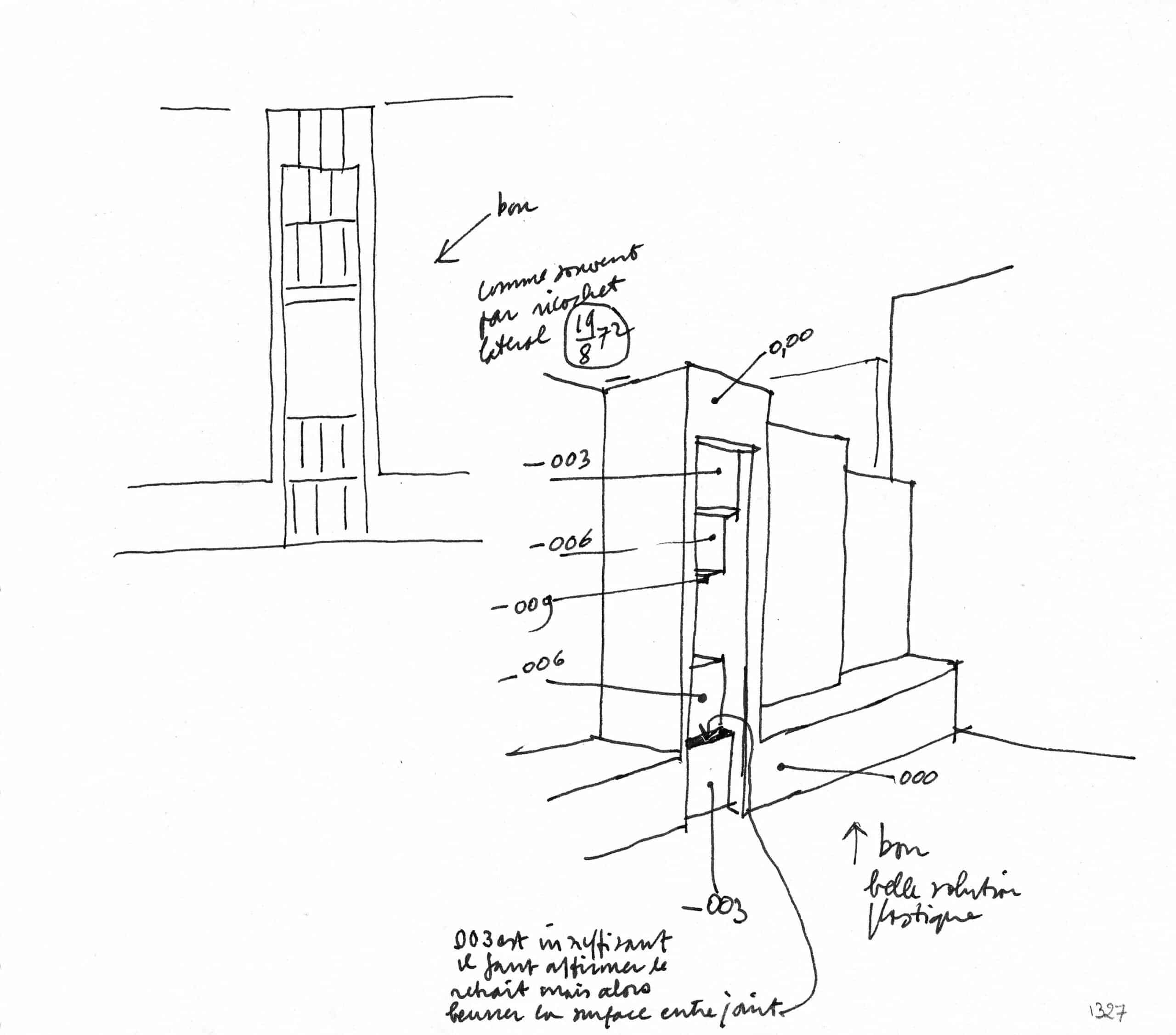

These are architects’ drawings. They are made for the project, to bring about its realisation, for at this moment it exists only in a delicate line on a thin sheet of paper. Let us look closely at these sketchbooks. They are inexhaustible. Everything is there, with no unnecessary chatter. The drawings cut to the essential. They are not decorative. They are made to explain and to be understood. No lies, no trickery here. They are precise, sometimes to scale. The different levels are articulated, and the number of steps that separate them. The sketchbooks capture the building to come in all sorts of ways. They see it from all angles. In plan first of all, the foundation of any project, and simultaneously, sometimes on the same page, in section, in perspective, partial or total. The drawings – that is to say the ideas, I insist – have the purpose of ensuring that the project is faultless, that there will be no nasty surprises later, when the files have been created and the building site established. The building site is the final sanction, which Simounet understands better than anyone.

Architecture is not a sham, a ‘skin’ as one says so hideously nowadays, that can be put onto anything. It comes from the interior, from the rules of proportion and lighting, of massing, and spaces. There is a truth there which cannot be compromised. On every page of the sketchbooks it is present, like the date, because this research, this will, this way of doing things, this work, is not the work of a moment but of an entire life, day after day. The work is life itself.

Evocative as they are, the sketchbook drawings are the very antithesis of what we call in our jargon ‘the rendering’ and which leads to all sorts of manipulations. They are the stark opposite. The sketchbooks swarm with little notations, captured as and when they appear. Here a shaft of light, there a material that will appear, or even a level that overhangs, or a horizontal that provides a reference. The drawings progressively elaborate the language of architecture that one recognises from one project to another, which will be his signature, his language, that is unique to him. The plans pass smoothly from sketchbook to drawing board, from free-hand to tee square, the next stage is always contained in the preliminary one. Thus is manifested the unity of thought.

These plans in themselves show us Roland Simounet at work. For example in the admirable Masion Domerc, the way in which the walls pass from the interior to the exterior, in which the rooms lead from one to another, how they are separated one from another by small intervals, the passages that contain these sequences, the variations in height, the finesse of recessed details. The work is magnificent here, in the sense that all this richness, instead of leading to a baroque mess to which numerous architects succumb, leads to a plan of extreme clarity, of fluidity and suppleness, which one would love to inhabit. All these qualities are found from one building to another for Simonet carries them with him and one sees them always fragmented, articulated, above all in those large projects where he is monitoring the scale, a constant preoccupation.

Simounet stopped at the time when mechanical drawing took the upper hand. From this time on the machine tends to take over. Soon architects will draw no more; they will not even know how to draw. What a tragedy. Already one can identify the buildings designed by machines, populating our towns, dumb as cenotaphs. What will happen to the Truth in architecture? How can we live without it? Let us look again at Roland Simounet who knew.

Translated by Susie Dowding from the original French. Excerpted from Pierre Riboulet, ‘De la verité en architecture,’ Roland Simounet à l’œuvre, Architecture 1951–1996 (Lille: Musée d’art moderne Lille Métropole, 2000), pp. 69–70.

– Lok-Kan Chau