Room at the Top?: Kate Macintosh, Denise Scott Brown and the Kingmaker-critic

All creative disciplines rely on the mythologies of heroes: intellectual bigwigs who shape a profession’s academic and visual frameworks. A lengthy period of university study gives plenty of time for architecture students to ruminate on which white, male ‘guru’ to call their own — Corb, Aalto, Rossi, Scarpa? Drawings are the medium of communication between guru and student, a shared language that translates not only a preference of style but also an ethos.

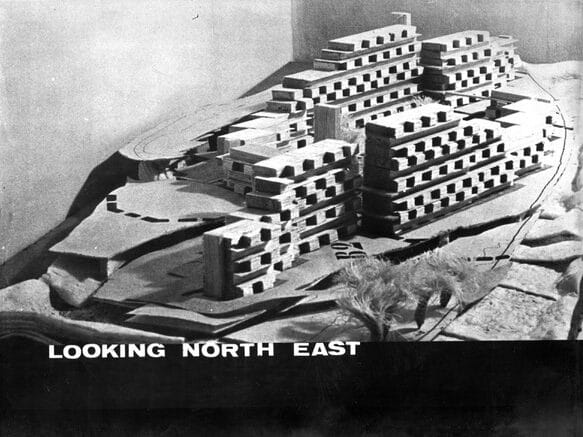

Although I had dabbled in Siza and Aalto during my architectural studies, in my third year I found my true calling in the work of Kate Macintosh. Riding the wave of 1960s and 1970s investments in social housing, Macintosh’s bold and humane architecture was overtly political, with a Scandinavian softness. I felt the grab. Dawson’s Heights — her 1972 social housing project in South London — had a stoic rebellion that I found inspiring. This was the kind of badass female architect I had been searching for.

Despite her achievements, the information available on Macintosh was painfully limited. Granted, she had contributed to a few collaborative books, but there were none dedicated solely to her, and the drawings available of her buildings were also frustratingly incomplete. At the same time, you could not move for books on the Smithsons, who had finished Robin Hood Gardens (now demolished) in the same year as Dawson’s Heights. Where was the book on Macintosh’s magnum opus? The obligatory manifesto or anthology?

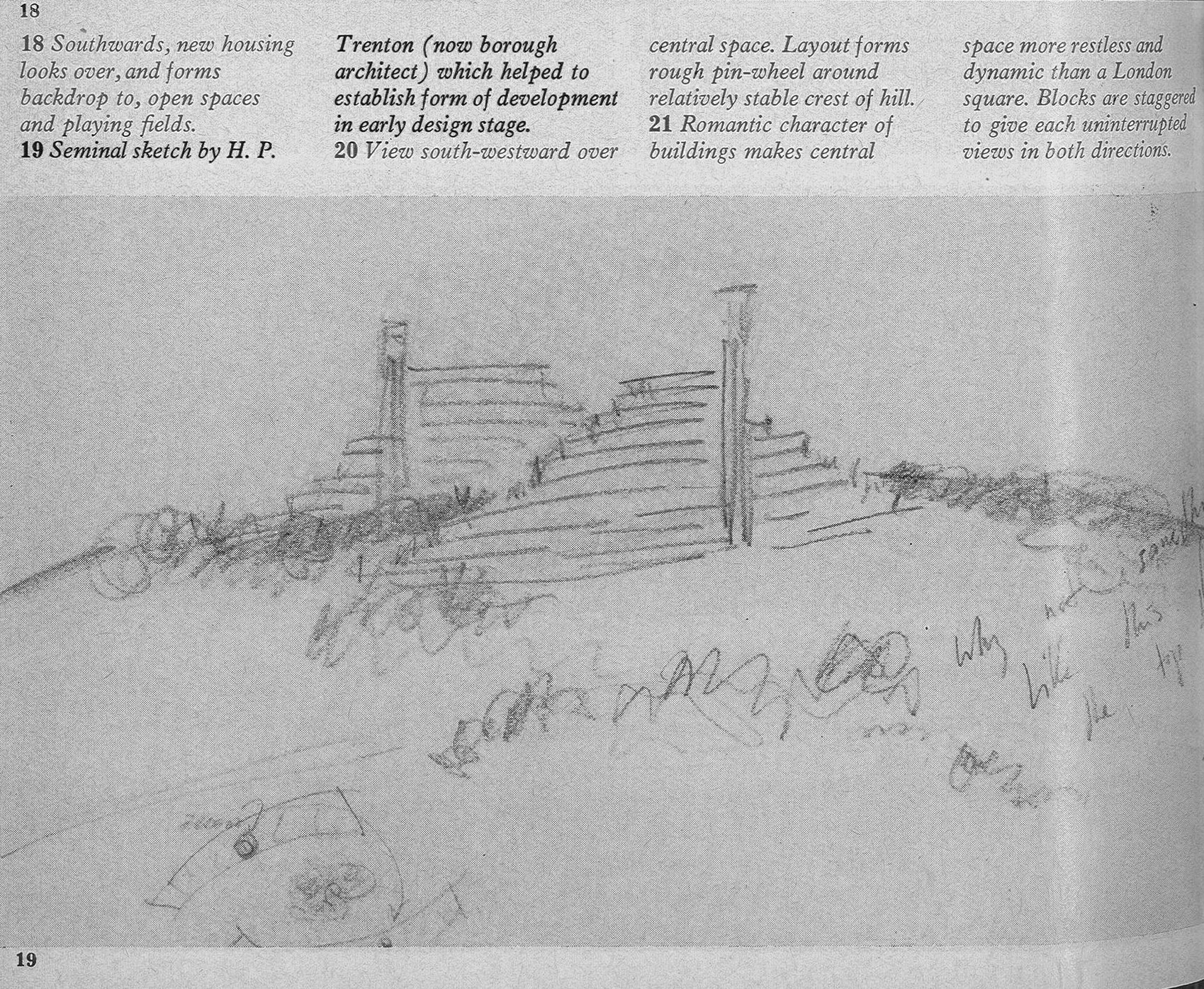

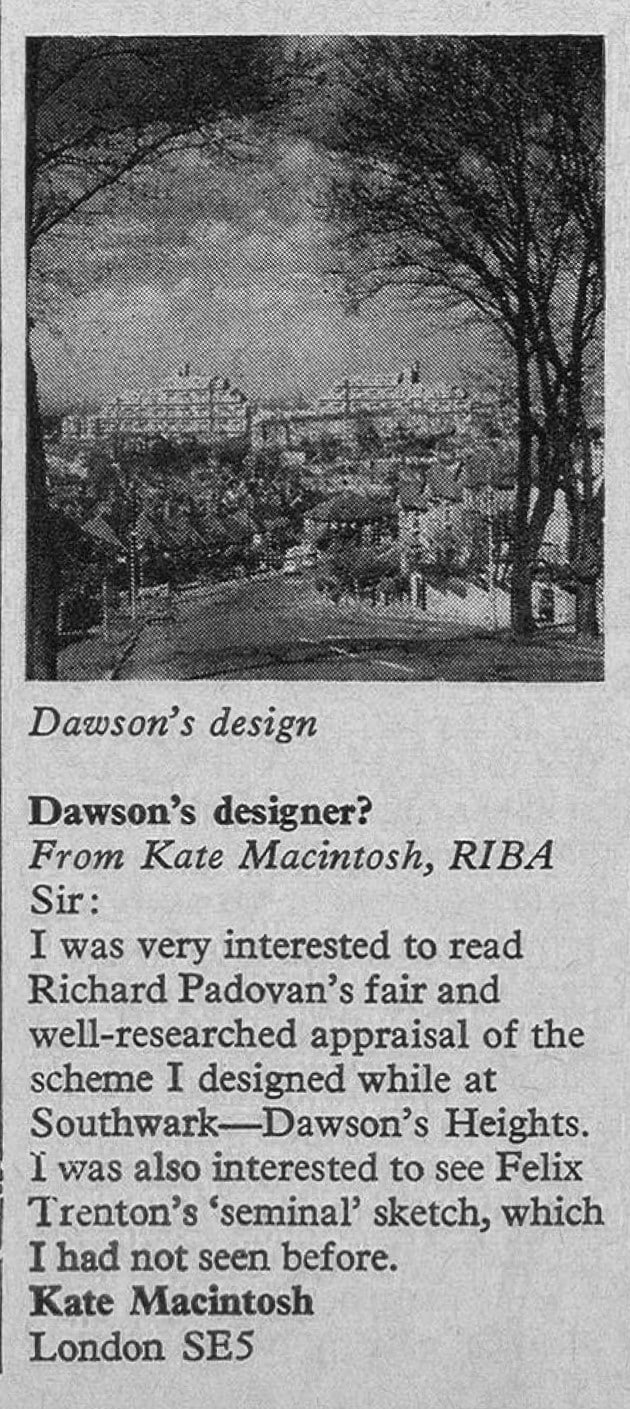

When Dawson’s Heights was published in the Architect’s Journal in 1973 Macintosh’s name was barely mentioned. The AJ did, however, illustrate a sketch attributed to H.P. ‘Felix’ Trenton, describing it as a ‘seminal’ drawing for determining the form of the development.

I later asked Kate about this article and this claim of authorship. She said that: ‘Trenton had absolutely nothing to do with Dawson’s Heights and the AJ journalist had worked in the Southwark office so he knew damn well that I was the designer’. [1] Macintosh challenged the misattribution of the drawing with a delightfully sarcastic letter:

All subsequent publications of Dawson’s Heights rightfully credited Macintosh with the design, which was almost entirely her own work. But the false claim in the AJ‘s initial article shows how the authorship of drawings can be made to deliberately disrupt the legacy of female architects. In the case of Dawson’s Heights, it took only a quick sketch by a jealous colleague and the cooperation of a journalist to result in the misattribution of Macintosh’s work, and the creation of a situation in which a woman must, once again, defend her rightful claim to her design. [2]

Like Macintosh, Denise Scott Brown also suffered due to the male media bias and the grey areas that result from architecture’s fundamentally collaborative nature. In the essay, ‘Room at the Top? Sexism and the Star System in Architecture’, Scott Brown describes how she began to ‘dislike [her] own hostile persona’ after her continual complaints about the misattribution of her work to Robert Venturi: ‘I watched as he was manufactured into an architectural guru before my eyes and to some extent, on the basis of our joint work and the work of our firm’. [3] But, as she identifies, ‘short of sitting under the drawing board while we are around it, there is no way for the critics to separate us out’. [4] Nevertheless, the historical default is to attribute work to men.

In Scott Brown’s essay, she further identifies the role of the critic in the guru-ism of architecture:

The critic in architecture is often the scribe, historian, and kingmaker for a particular group… The kingmaker-critic is, of course, male; though he may write of the group as a group, he would be a poor fool in his eyes and theirs if he tried to crown the whole group king. There is even less psychic reward in crowning a female king. [5]

These words describe how a male media lens distorts the authority of female architects. The ‘star system’ seeks a singular male individual to name ‘King’, and is fundamentally uncomfortable with the idea of female power. Historically, as architectural critics have been predominantly male, women architects have public reputations that are shaped by men. Perhaps, the question is not who are the gurus, but who created the gurus.

Through this ‘male gaze’, the ‘star system’ tends to produce three categories of women within architectural history:

- The Undervalued: Women, like Kate Macintosh, whose contribution to architecture is underestimated and under-documented in architectural discourse.

- The Mrs: Women, like Denise Scott-Brown, who history side-lines in favour of their husbands.

- The Missing: The unseen architects who have contributed towards architectural discourse but remain unrecognised.

In each of these cases, the ‘star system’ diminishes the woman’s role in the cultural production of architecture. At the heart of this condition is that architectural history and theory is uncomfortable with co-authorship. Architecture practices are traditionally perceived as an organisational pyramid with one (male) individual at the top.

Both Macintosh and Scott Brown worked amid the critiques of the 1960s and 1970s — structuralism and post-structuralism — which viewed architecture more as discourse than as an individual’s work of art. The ‘star system’ remains pervasive, however, and is compounded by an educational system that lionises male architects. As a result of a historical media bias, we have inherited a drawing lineage that excludes female architecture. And we must remember that this, in turn, has significant influence over contemporary architecture students.

In 2021, the proportion of male to female students is 1:1 in most architecture schools, and yet the offering of female ‘gurus’ is painfully limited. It must be recognised that the lack of female representation within architectural history plays a crucial role in this condition.

While we have made significant steps in moving away from the ideas of originality and singular authorship – practices are more comfortable with the terms ‘collective’, ‘ensemble’, and ‘studio’ –, history and theory are too important to architectural education to rely on contemporary practitioners as the only role models for young women. As architecture is a precedent-based discipline, to accept today’s version of architectural history is to do a disservice to architects like Macintosh and Scott Brown. We must expand our drawing archives to include the work of women architects.

History is not an inert substance: if agitated, new bubbles can rise to the surface. Kate Macintosh’s recent W Prize for her work in the 1960s and 1970s is proof that we can re-evaluate our inherited history to find new, more equitable constellations within this ‘star system’.

Emily Dan is currently studying Architecture at Glasgow School of Art.

This text was submitted to the Student Archive category of the Drawing Matter Writing Prize 2021.

Notes

- Kate Macintosh, interview with author, 23 December 2020.

- Macintosh subsequently convinced the RIBA drawings collection of the spuriousness of the sketch, and it was no longer listed as an authentic document.

- Denise Scott Brown, ‘Room at the Top? Sexism and the Star System in Architecture’ from Ellen Perry Berkeley (ed.) Architecture: A Place for Women (1989). Although some journalists in the 1970s referred to ‘Venturi’s ducks’ from Learning from Las Vegas, this analogy was invented by Scott Brown.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

– Raphael Haque