Sigurd Lewerentz: Architect of Death and Life (2021): Review and Excerpts

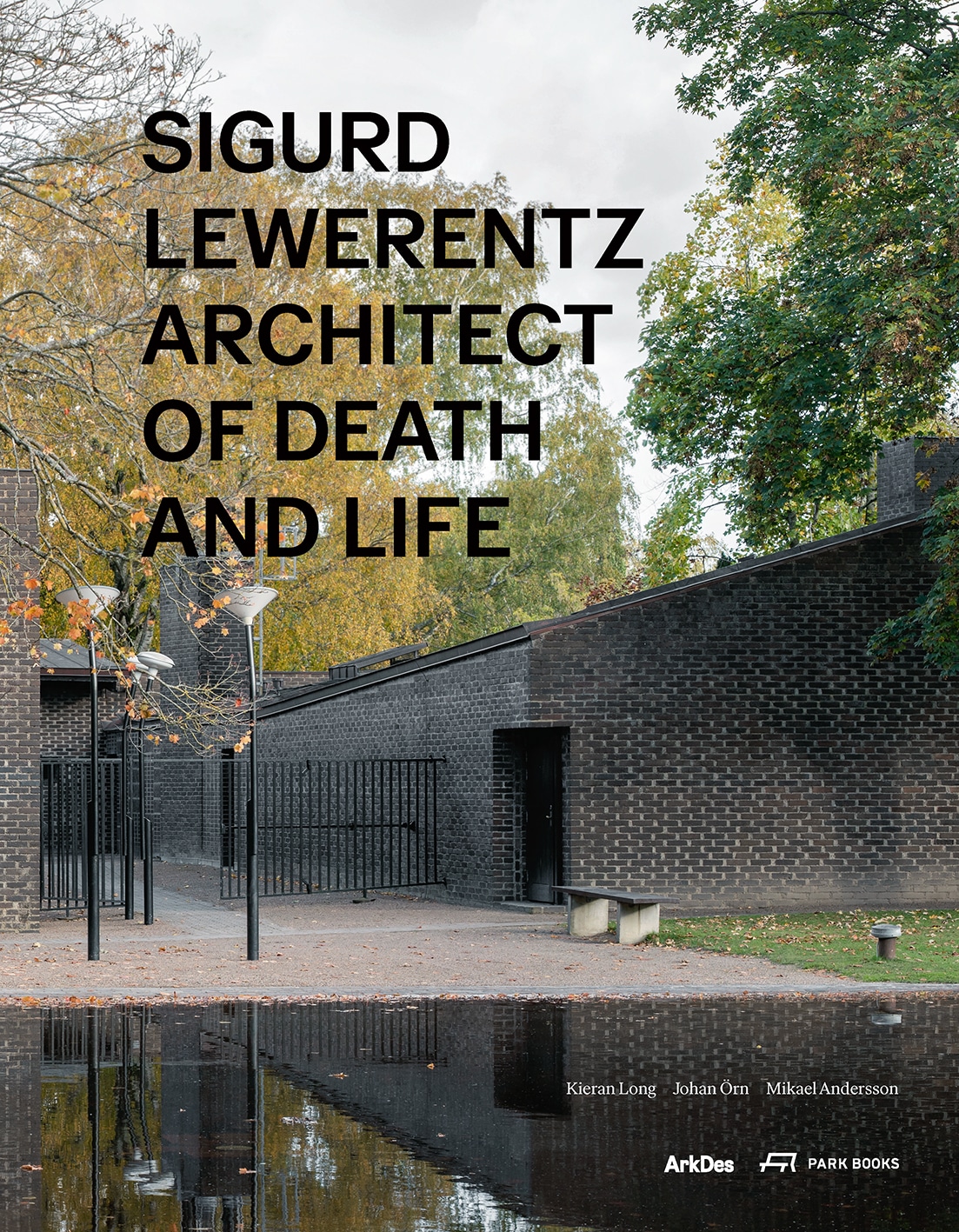

The new monograph Sigurd Lewerentz: Architect of Death and Life has arrived, published by ArkDes and Park Books to accompany the exhibition that opened in Stockholm in October 2021 curated by ArkDes director Kieran Long with scenography by Caruso St John Architects (open until August 2022). As an excellent preparation to the exhibition and for developing a deeper understanding of Lewerentz’s historiography, it is advisable to purchase the book in advance of your visit from your local bookshop: the book, with its more 300 drawings from the ArkDes archives, is meant for study on a steady table and not as a travel companion. Four years of research results in four sections: an introduction on the position and reception of the work by Kieran Long, a historiography by Johan Örn, notes on the archive by Michaël Anderson that includes the drawings, and a series of newly commissioned photographs by Johan Dehlin.

St Peter’s Church, Klippan © Johan Dehlin.

Every (western) architect knows the churches and chapels of Sigurd Lewerentz (1885-1975), with their exceptional material intensity that induces a powerful awareness of one’s own individual and physical existence made present through Lewerentz’s reinvention of ritual, symbolic form and the act of making. His later work, especially St. Peter’s church in Klippan (1962-1966) with its tilted floor, walls and barrel-vaulted ceiling lined with brick, and the St. Mark’s church in Björkhaven, Stockholm (1956-1960), are the subjects of architectural pilgrimages as well as of scholarly research. These buildings answer a longing for the essential, for an authentic experience. Their detailed material and almost primitive craftmanship (Lewerentz moved house so that he could be at the site almost daily), the perspectival proportions and sublime capturing of daylight and darkness, has inspired previous detailed research and reflection. For example, young Swiss architects Helena Brobäck and Raphael Zuber redrew St. Peter’s stone by stone, aiming to capture the unconventional brick joints and the uneven patterns on the floors as an inspiration for their own work. Scholarly attention paid to these two buildings, such as Patrick Lynch’s deep reading of the St Peter’s in connection to Lewerentz’s liturgical advisor, Lars Ridderstedt (Civic Ground, 2017), has enabled an ever deeper understanding of the architect’s design intentions.

Cemetery Chapel, Kvarnsveden © Johan Dehlin.

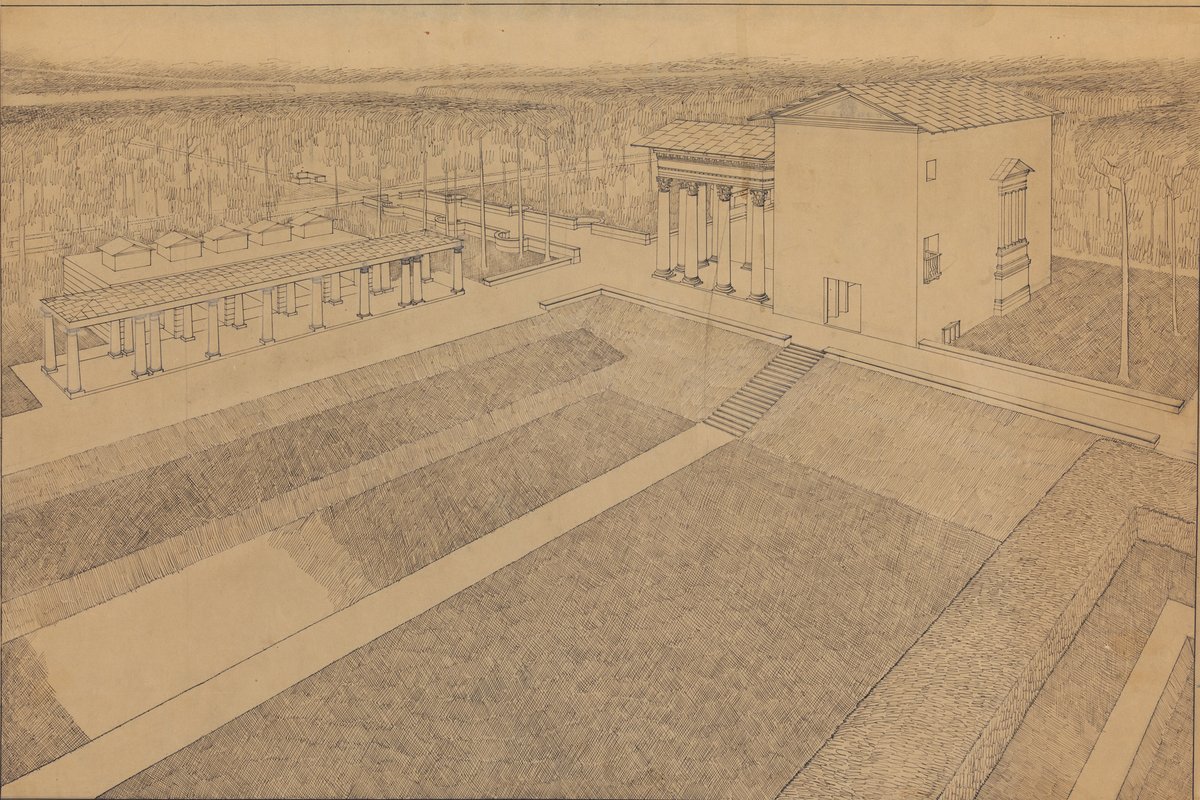

At a slower pace, the refined and austere classicism of Lewerentz’s early work has also gained recognition. Janne Ahlin’s wonderful book Sigurd Lewerentz, architect (1985 translated 1987, reissued by Park Books in 2014) was the first to cover more of Lewerentz’s oeuvre, although still mostly focusing on the chapels and cemeteries and linking them to their context and the architect’s environment and influences. In 1915, aged 30, Lewerentz and his colleague Gunnar Asplund won a competition to design a new cemetery in Stockholm. Their winning proposal became what is now known as the Woodland Cemetery, a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1994. While Asplund focused on the cemetery’s buildings, Lewerentz took charge of the landscaping, creating a deep-rooted connection between the site, a former gravel pit overgrown with pine trees, and its surrounding natural terrain. Gravestones are embedded among the trees, while footpaths swirl in-between reflective water ponds and grassy hills. The single building designed by Lewerentz, the Chapel of Resurrection (1922-1925), is regarded as a prime example of Nordic Classicism for its austere and vertical proportions and its ornate entrance portico. Drawing on a re-reading of classical themes as order and (shifted) symmetry, the ritual routes and gestures of mourning are enhanced through the blending of building with landscape. The designs for several later cemeteries, such as the Malmö Easter Cemetery, all develop from the same relation with the natural landscape, and within them, the chapels are testimonies of the evolution of architectonic expression with a close relationship between material and detail.

Long’s introduction gives a comprehensive overview of research on Lewerentz, offering a network of possibilities for further reading. Discovery of Lewerentz’s work outside Sweden seems to come mostly from the United Kingdom and Italy, starting in 1966 with Reyner Banham’s mention of St. Marks church in his book The New Brutalism, which he describes as ‘the hardest case’. Full international recognition came over 30 years later, when Wilfried Wang published Sigurd Lewerentz: Drawings in 1997. This followed a show of the work at the 9H Gallery in London, an important platform for bringing attention to architects who fell outside the mainstream postmodernist current. In the same period Colin St. John Wilson started writing inspirational texts about Lewerentz’s sacral buildings as metaphysical, metaphors of brooding mystery, including ‘Sigurd Lewerentz, The sacred buildings and the sacred sites’, while Adam Caruso highlighted the mastery of building and the existential character in his essay ‘Sigurd Lewerentz and material basis of form’, exploring Lewerentz’s synthetic way of working where issues of construction and thematic intent become one. Both texts were published in the journal OASE nos.45-46 (Essential Architecture, 1997). In Italy the monograph Sigurd Lewerentz, the sacred buildings and the sacred sites, edited by Nicola Flora, Paolo Giardiello and Gennaro Postiglione, was first published in 2002.

The publications mentioned above, all written by practicing architects, aim to come as close to the work as possible. They want to BE the building, drawing the reader inside an enigmatic sacredness through a close reading with original drawings and detailed photography. Lewerentz himself is absent or depicted as an enigmatic, almost mythical figure. Ahlin’s book, mentioned above, opens with a photograph of Lewerentz sitting at a table surrounded by drawings; he is not drawing but shown in contemplation while lighting a cigar. His thick black spectacles place him with other mythologized architects such as Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe. But while these pioneering architects sought to engage internationally within an architectural dialogue, and thus influencing the architectural culture of their time, Lewerentz did not endeavour such things. He did not teach. Moreover, he declined invitations for lectures, including Alison and Peter Smithson’s invitation to talk at the Architectural Association in London, which added to the mystery of his genius.

This book is different.

It is not ‘a building’, it is ‘a library’, written in the archives. Aiming to go beyond mythologies, hagiographies and interpretations, the focus is not only on Lewerentz’s work, but also his life, and the perspective is historiographical. Who was Sigurd Lewerentz? Where did his extraordinary work come from? How are we to understand it? These are some of the questions the book intends to answer. ‘We hope to bring forward a new baseline of evidence for this most mythologised of architects and to provoke fresh insights into his legacy,’ Long writes in his introduction: ‘It is this possibility of a ‘conversation across time’ that Lewerentz holds out to us.’ Between Lewerentz’s early work and the last magnus opus, there is a whole life of evolutions and progressive insights, a life full of engagement within society.

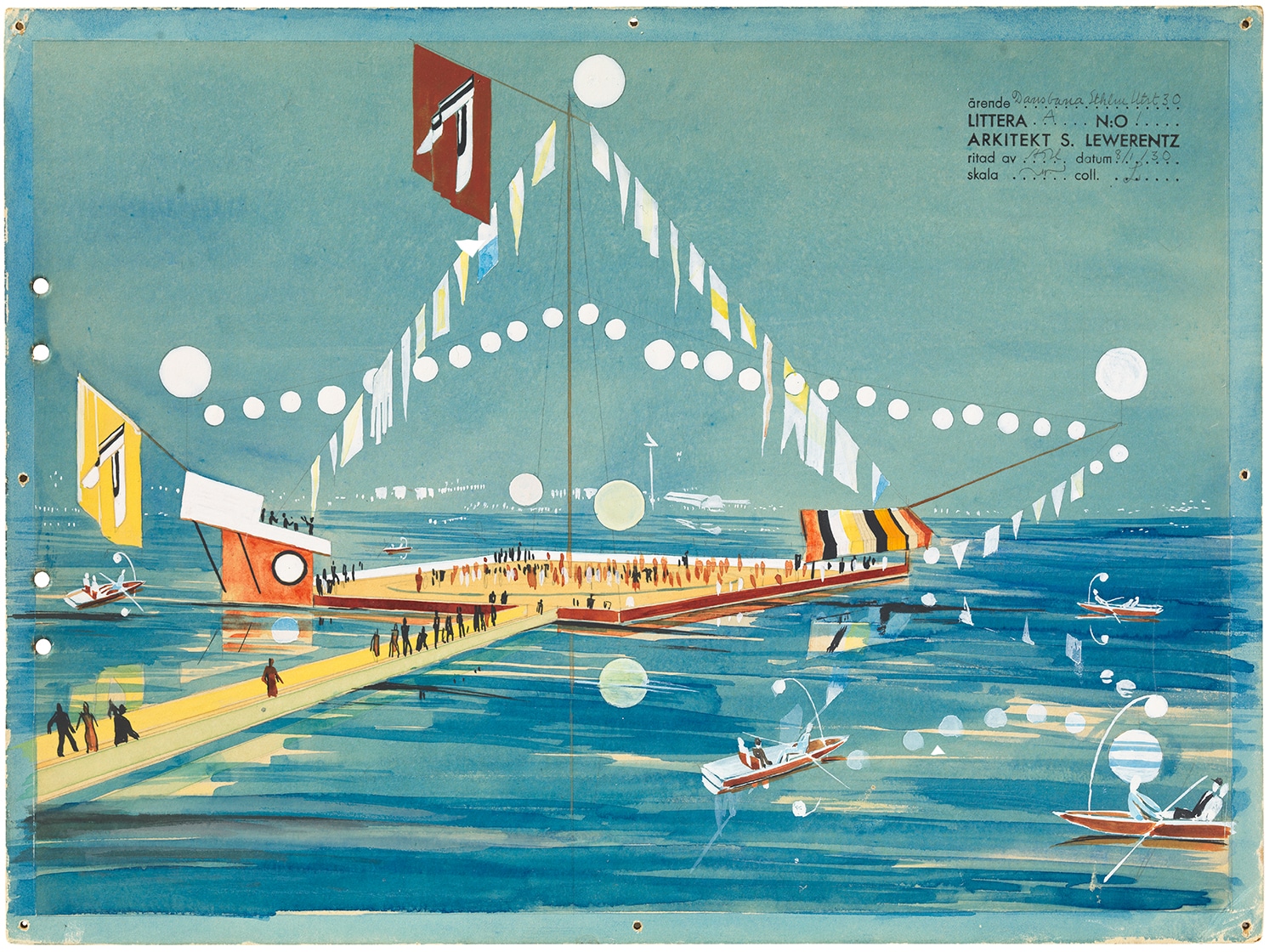

Sigurd Lewerentz (1885–1975), Floating dance floor, Stockholm exhibition, 1930 © ArkDes collections.

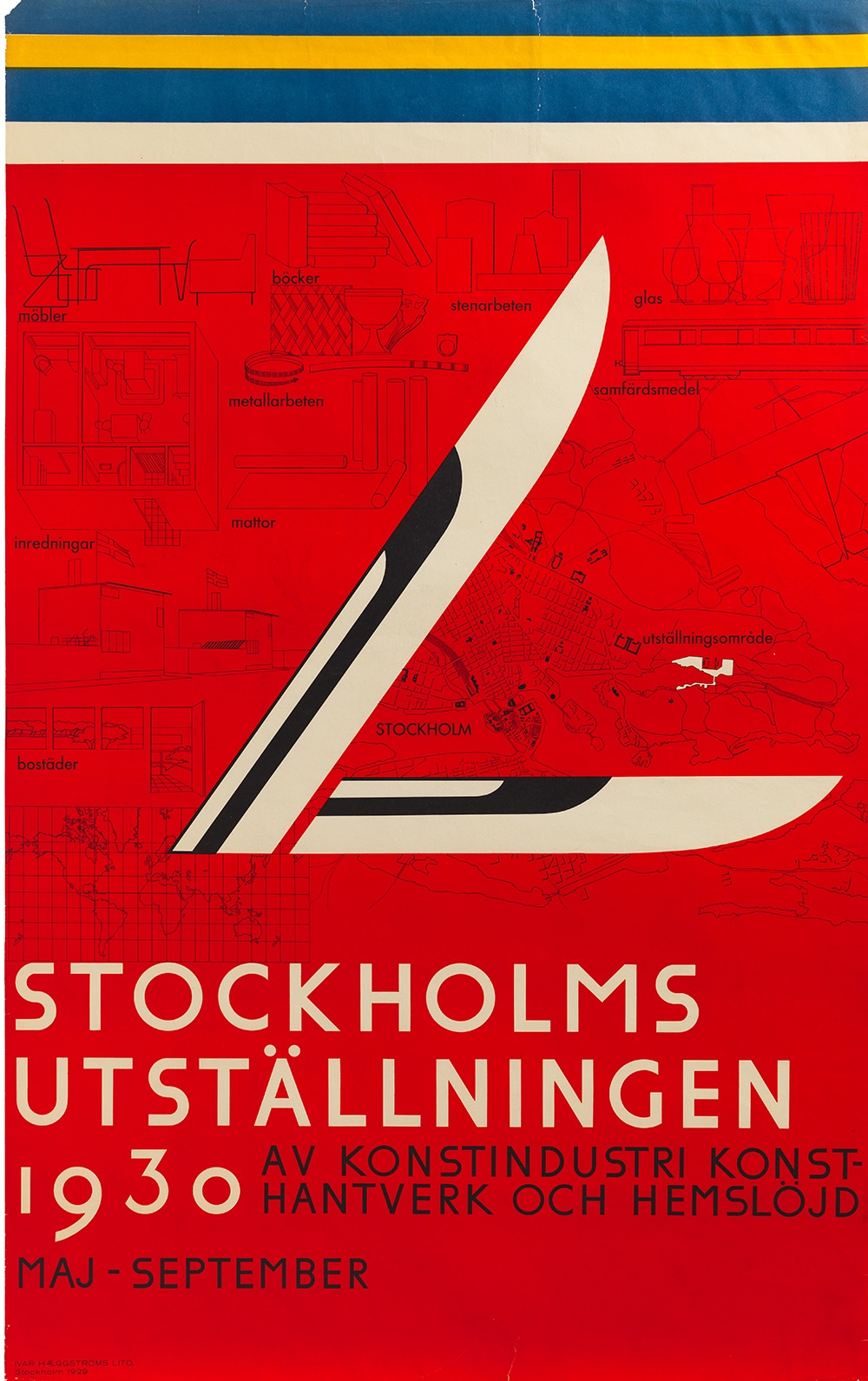

‘A floating dance floor with fluttering flags and hovering light globes – elegant flaneurs contemplating a futuristic exhibition stand – a cocktail party taking place in an ultra-modern apartment: all of these feature in the perspectives that Lewerentz and his assistant Anders Hedberg (signed AGH) produced for the Stockholm Exhibition. Other drawings show more sudued, almost dream-like images of a large villa. Lewerentz’s work for the exposition was extensive and varied: he designed homes, exhibition stands, a grand piano, wallpaper, luxurious furniture, posters, neon signs, headstones and even liveries for a bus company; In addition, he built a temporary structure, the lakeside café Gröna Udden. His most significant contribution, however, was his graphic design. He created the exhibition logo – the stylized pair of wings placed on top of the exhibitions’ central 80m-high advertising mast and found on everything from the official poster to flags and other memorabilia.‘

This is the goal of this new publication: not to depart from the buildings in their autonomy, but to start from Lewerentz as a practitioner who connected with human life at almost every level. Örn’s biography does this through a chronological grouping in five themes: ‘The Architect’s Path’; ‘Metropolitan Modernist’; ‘Architect and Manufacturer’; ‘The Church Architect’; ‘A Living Legend’, and it is wonderful to read about the long period between the major works, when Lewerentz took on more everyday projects. In 1930, he and Asplund were designated head architects for the Stockholm Exhibition, a four-month fair that encouraged Swedish citizens to engage with modern ways of living.

Sigurd Lewerentz (1885–1975), poster for the Stockholm exhibition, 1930 © ArkDes collections.

Fashion, mundane city life, the role of functionalism, standardization and mass production, all come to life in the drawings shown in the book. The fair’s distinctive wing-shaped logo, the designs for exhibition stands, temporary cafés and display homes of the future, as well as the wallpaper, furniture and musical instruments that Lewerentz imagined would appear inside are all illustrated. Equal attention is given to the National Insurance Board in Stockholm (1932), a rationalist office block with a cavernous internal oval courtyard, with Lewerentz’s custom-designed pieces produced by Blokk (later known as Idesta) – a company he co-founded, and which was dedicated to making furniture and interior fittings. Also highlighted is Lewerentz’s collaboration in the design of the Malmö City Theatre (1933-1944), a steel-framed functionalist ensemble with a tiled horizontal and vertical rhythm. The drawings in the book illustrate the project from the first design sketches to some of the details, interlaced with original documents and photographs, but it is a shame that some of the very fine pencil drawings are difficult to read, a problem that occurs in other Lewerentz publications. The originality of the material and numerous sketches, perspectives and details make up for that in part, and the evolution that is depicted through the drawings is very insightful, making it possible to make comparisons across time and scale.

‘Malmö City Theatre was the subject of two architectural competitions of the 1930s. Lewerentz won both the open competition of 1933 and the subsequent invited competition for the shortlisted entries of 1935. The theatre looms large in the background of one perspective – a night-time view – made for the second round. In the foreground we see a cluster of trees and beyond it cars and theatregoers. A large sign declares that evening’s performance is by ‘Trudy Schoop’ – a Swiss dancer who had visited Stockholm that year. The competition jury was impressed by the proposal, the local people distinctly less so. The city council’s solution was to ask Lewerentz and the winners of the second prize – David Helldén and Erik Lallerstedt – to collaborate on the design of the new theatre. Traces of both proposals can be seen in the theatre, which was completed in 1944. Lewerentz’s efforts were focused on the technical aspects and acoustics of the auditorium and stage; among other things, he devised an innovative system of sliding partitions that could be used to subdivide or open up the auditorium.‘

In a society that is governed by a mass culture that thrives on the technological and virtual, the immediate experience of a well-crafted building and the authentic attitude of an architect who created buildings as tangible communities, are still highly viable and inspirational. Lewerentz eventually defied any international style, from modernist to post-modernist, in order to create an architecture that is primordially human. What are we to defy today to follow this inspirational path?

St Mark’s Church, Björkhagen © Johan Dehlin.

Sigurd Lewerentz: Architect of Death and Life (2021), edited and with texts by Kieran Long, Johan Örn, and Mikael Andersson, is published by Park Books and ArkDes. The book can be purchased here.

Caroline Voet is a Belgian architect and Professor at the Faculty of Architecture, KU Leuven.