The Cottage at Bromley

– Tim Anstey and Mari Lending

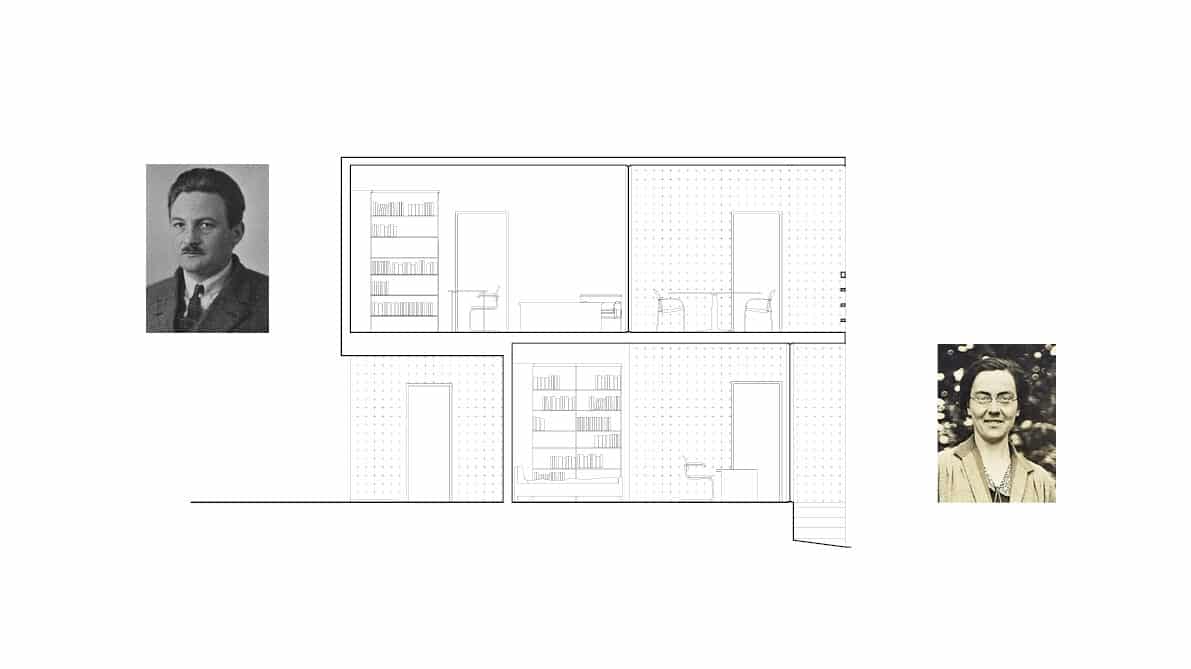

Enjoyable finds in archives often emerge between the lines. Inside RIBA Collections, which is organised to form a narrative celebrating architects and their works, we found a gem of modern cultural history, consisting of three architectural plans and four letters (ten pages altogether, eight in transcript, two typed). [1] The material relates to a project carried out between summer 1934 and January 1935 by the architect Godfrey Samuel to design a ‘Cottage at Bromley’ for two clients, Dr Fritz Saxl and Dr Gertrud Bing.

The discovery was made by accident. We were tracing the building history of the Warburg Institute (Hamburg and London) in a project on the significance of architecture for Aby Warburg’s interrogation of cultural history. Bing and Saxl were the director and assistant director of the Institute who, in collaboration with many others, were able to orchestrate the removal of Warburg’s iconic library from Hamburg in 1933, as National Socialist politics threatened both its activities and its existence. [2]

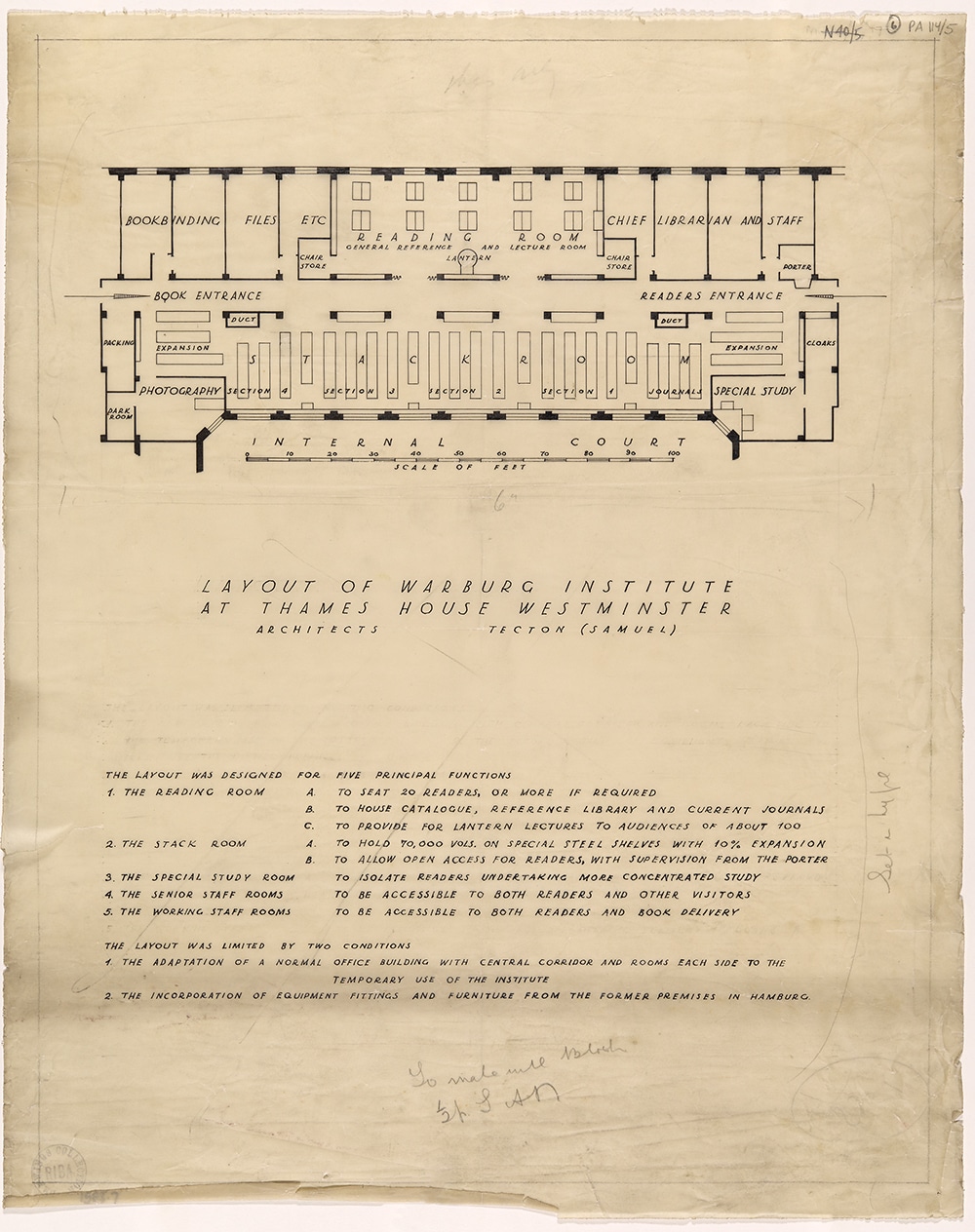

We had discovered a detail that intrigued us but which no one else had thought to investigate further. It turned out that the designs commissioned by the Institute to house the library in London (on the ground floor of Sir Frank Baines’ monumental and newly constructed Thames House on Millbank) had been prepared by Tecton, under the supervision of one of its five student founders, Godfrey Samuel (who left the collaborative in 1935, was the architect of a series of elegant modernist houses in partnership with Valentine Harding among others, and who later became chairman of the Royal Fine Art Commission).

Sensing a story, and with an element of serendipity, we typed both ‘Tecton–Saxl’ and ‘Bing–Samuel’ into the RIBA catalogue search engine. The former turned up, as we hoped it would, a complete account of the elegant, tightly planned modernist interior that Tecton designed for the Institute at Thames House. As we pressed ‘search’ on the latter, up came an entirely different project, magical and wholly unexpected. As well as collaborating intimately in saving and running the Warburg Institute, Bing, 42 years old, German by birth, and Saxl, 44 years old, Viennese by birth had commissioned from Tecton a house for a life together in the new capital. Inside the RIBA collection, this collaboration unfolded in all its peculiarity through archived drawings and letters.

Alighting in London

The story has something of the aura of an Agatha Christie novel, involving long train journeys, heavy furniture, genteel hotels, and, its own theme, a passionate recalibration of the idea of art history. Saxl, on the recommendation of Ernst Cassirer, one of the supervisors of Bing’s doctoral dissertation, had appointed Bing to the staff of the Institute in December 1921. During the later 1920s Warburg and Saxl in a sense competed for Bing; Bing acted as Warburg’s muse; he trained her in his mode of study, and the two of them went to Florence in 1927 and again to Italy for a nine-month trip in 1928–29. Wives, colleagues and lovers existed in intimate proximity. It was Bing who found Warburg dead in his study after a dinner at his home in Heilwigstrasse in Hamburg in 1929 (she had been upstairs talking to his wife). One can imagine Hercule Poirot narrowing his eyes and stroking his mustache contemplating this history. In 1930s London, although central actors in the plotline had been dispatched (Warburg dead; Saxl by then separated from his wife Elise), discretion prevailed and the nature of director Saxl and assistant-director Bing’s partnership remained elusive. It was structural – but was it romantic? History concludes: ‘maybe’, ‘most definitely’, ‘presumably’. From the late 1930s, they lived together in a semi-detached house at 162 East Dulwich Grove. A single dwelling, and the context for much mutual entertaining, it was nevertheless accessed via two separate entrances. [3] Bing, having edited Saxl’s lectures after his death in 1948, left his and her correspondence in the Warburg Institute Archive untouched. She asked that all her private correspondence be destroyed after her death in 1964.

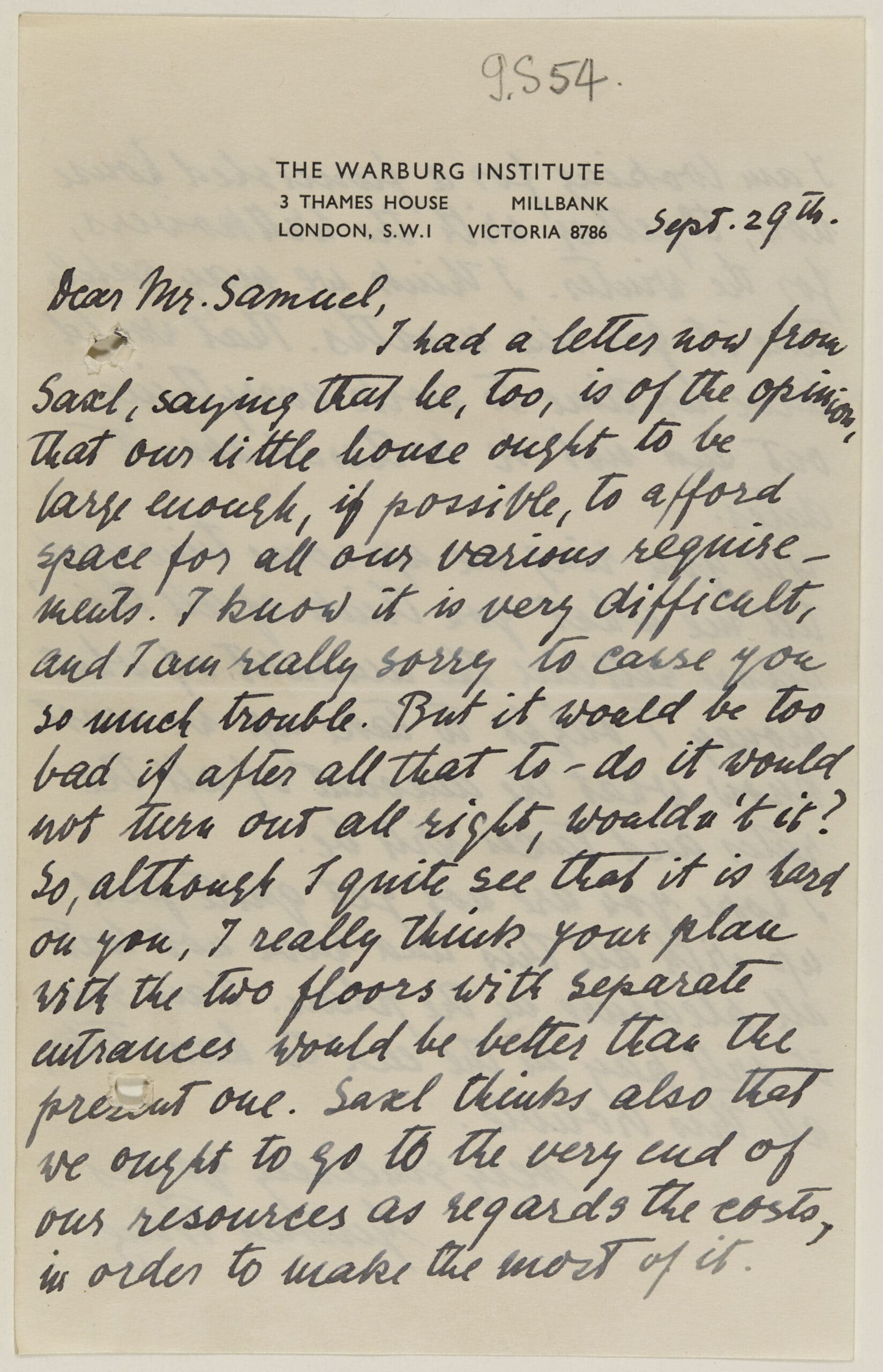

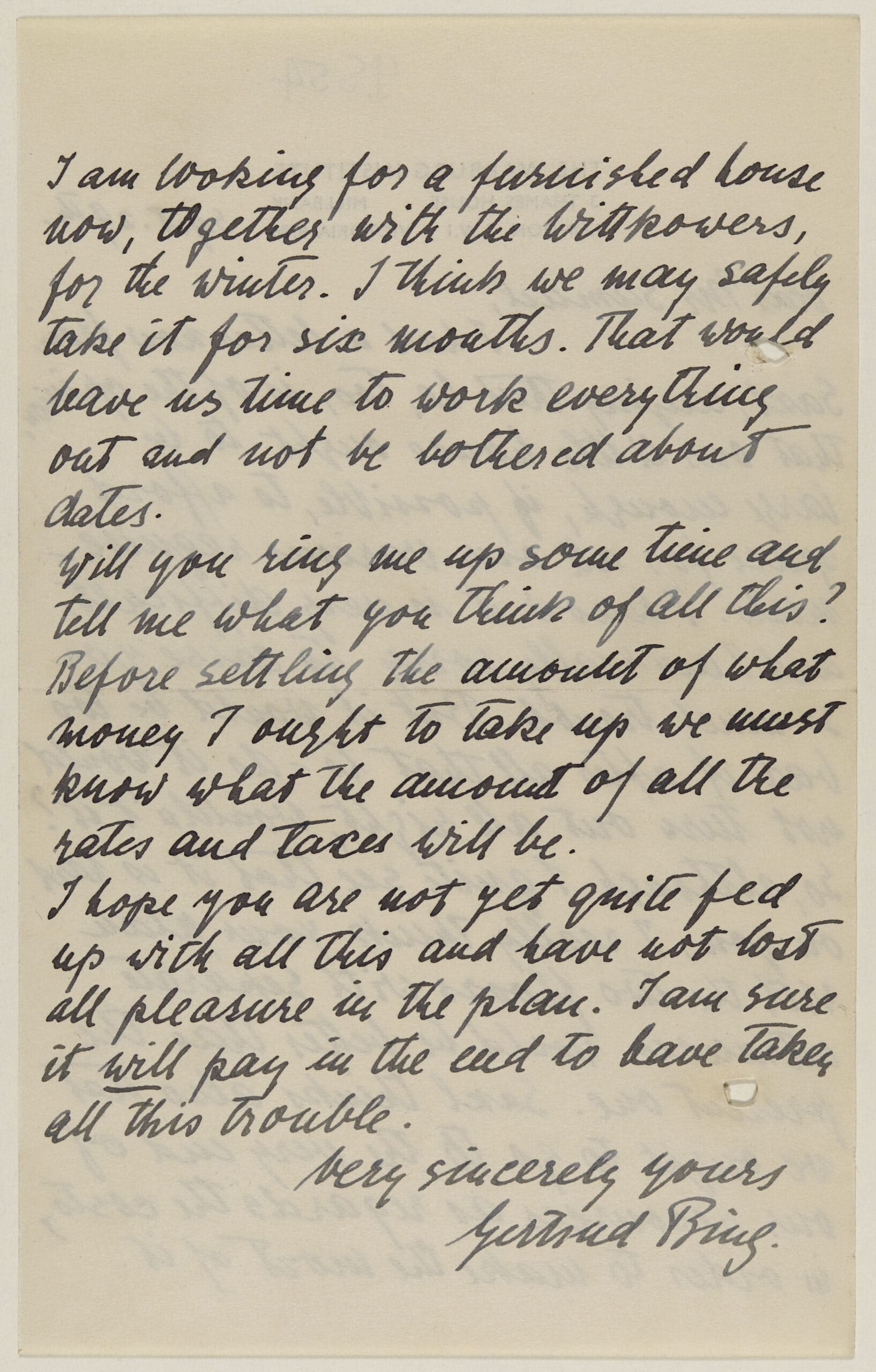

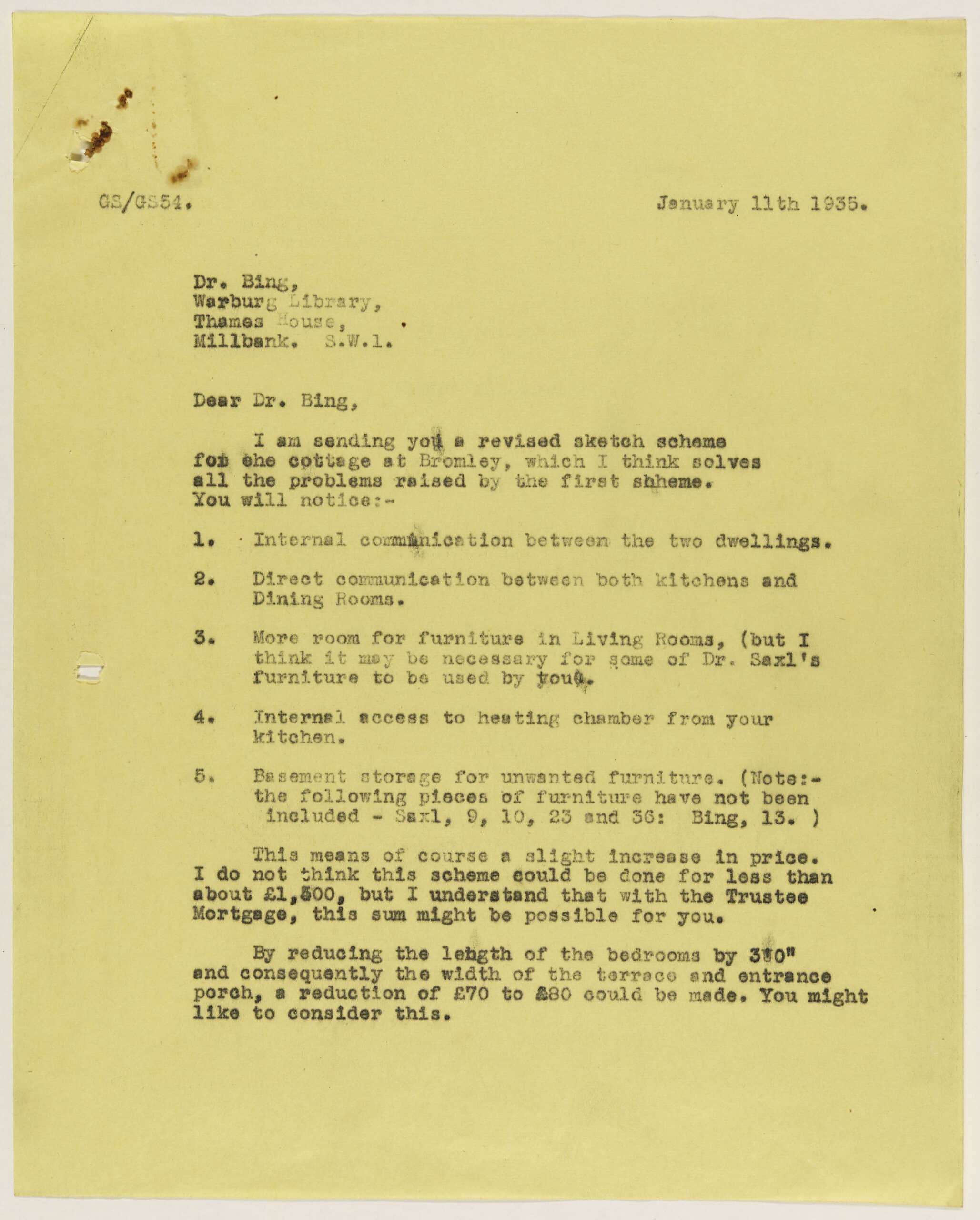

Agatha Christie, who lived in Wells Coates’ and Jack Pritchard’s ISOKON building (1934) in the 1940s and who was an evocative portrayer of Tecton-like buildings and interiors, once had a young British architect ponder: ‘Anyone who wants something decent built hasn’t got the money, and those who have the money want something too utterly goddam awful!’ (Dead Man’s Folly, 1956). From the RIBA correspondence, it is evident that Bing and Saxl belonged to the former group: ‘Saxl thinks also that we ought to go to the very end of our resources as regards to the costs, in order to make the most of it,’ she conveys to the architect in September 1934.’ ‘Shall we be able to bear the costs?’ she worries in December: ‘We must know… the amount of all the rates and taxes.’ ‘I do not think this scheme could be done for less than about £1,500, but I understand that with the Trustee Mortgage, this sum might be possible for you,’ the architect writes in January 1935.

These letters preserved in the RIBA archive are one of the earliest places where the Bing-Saxl ‘We’ is recorded on paper. ‘I am looking for a furnished house now, together with the Wittkowers, for the winter,’ Bing writes to Godfrey Samuel in September 1934, on Warburg Institute letterhead: ‘I think we may safely take it for six months’; this ‘would leave us time to work everything out and not be bothered by dates’. She and Saxl imagine a ‘little house’, ‘large enough, if possible, to afford space for all our various requirements.’ In correspondence with a young modern architect, Saxl and Bing’s (publicly) wordless structural symbiosis becomes articulate; their intimacy can emerge.

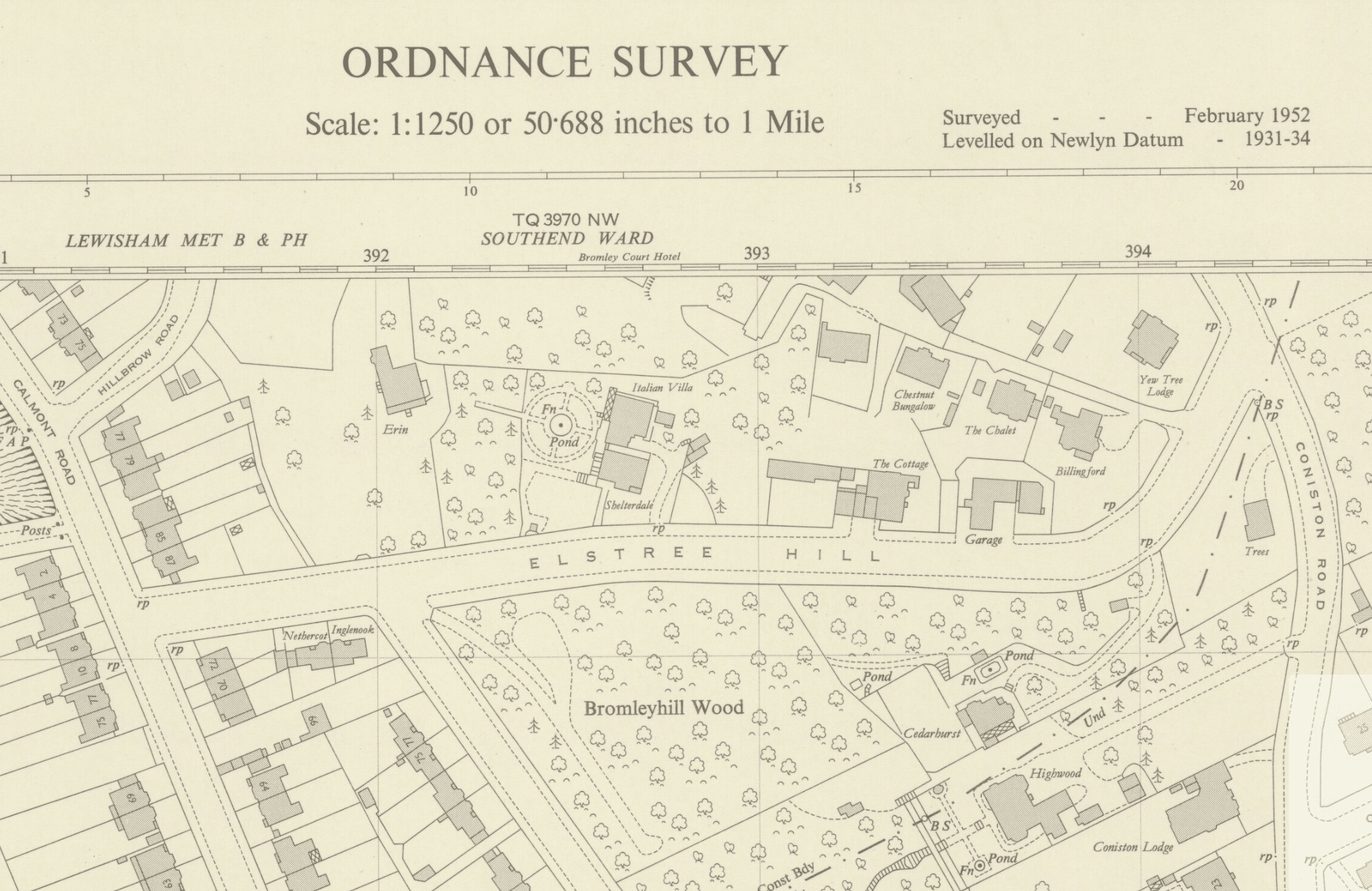

All this informs the drawings Godfrey Samuel prepared for a site on the slopes of Elstree Hill in the autumn of 1934, where the modernity, not to say the modernism that characterises the story of Warburg’s institute coloured a project for the two renaissance scholars’ home, at once double and private. If the ambiguous details of Bing and Saxl’s history would have awakened Hercule Poirot’s interest, the physiognomy of the house Samuel designed for them would have struck his contemporary investigator of the workings of the little grey cells, Sigmund Freud.

Two front doors

Godfrey Samuel Papers, Series 2: Projects undertaken by Samuel, 1933–1938.

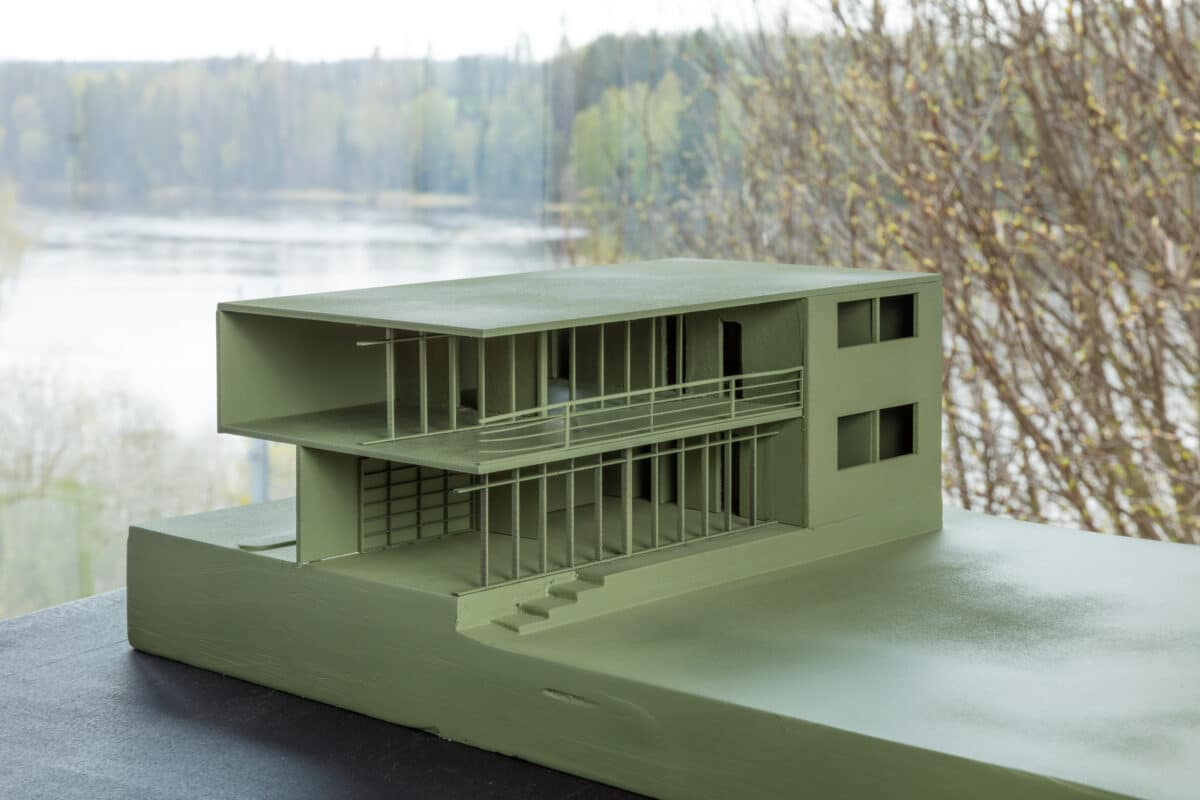

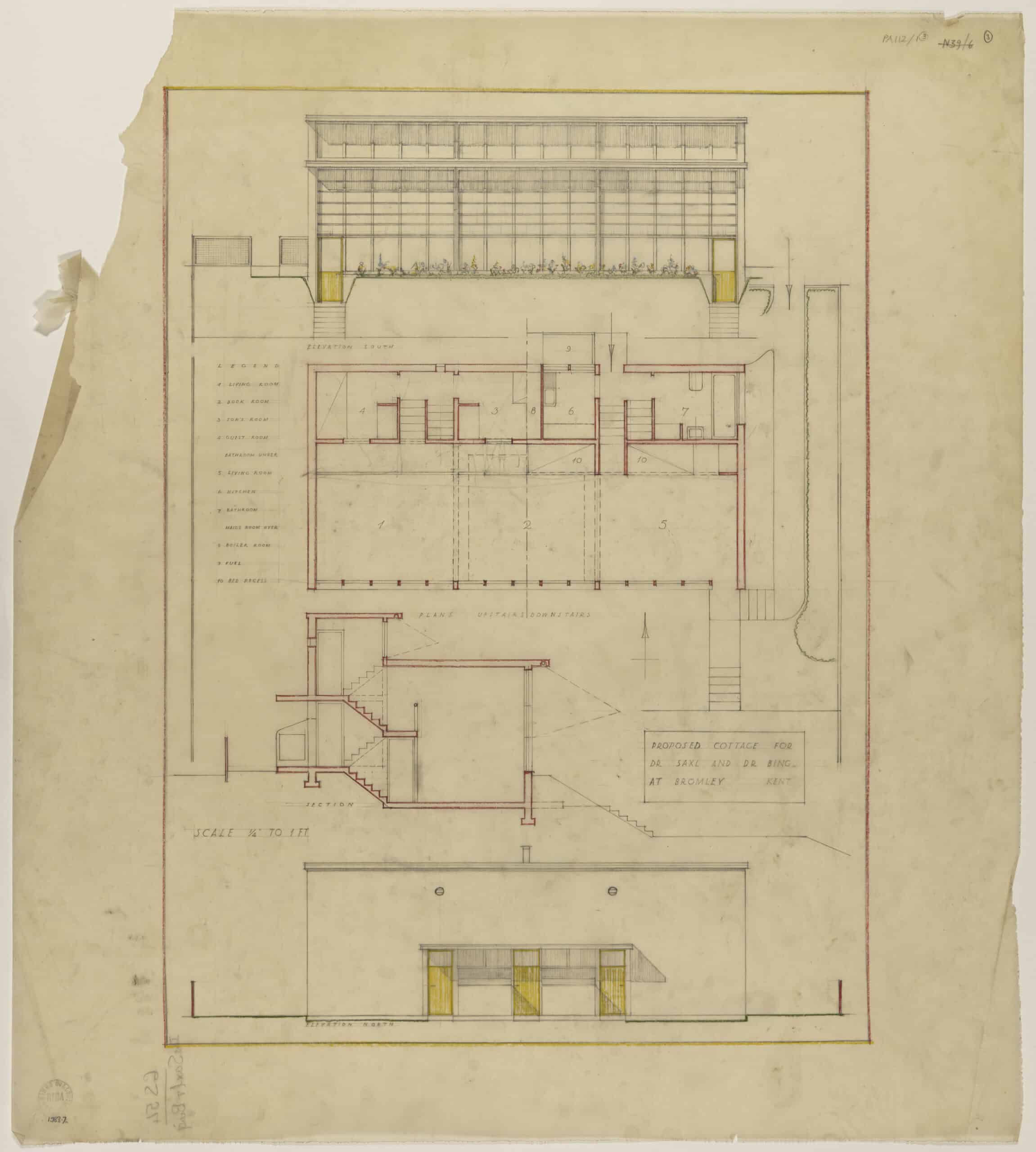

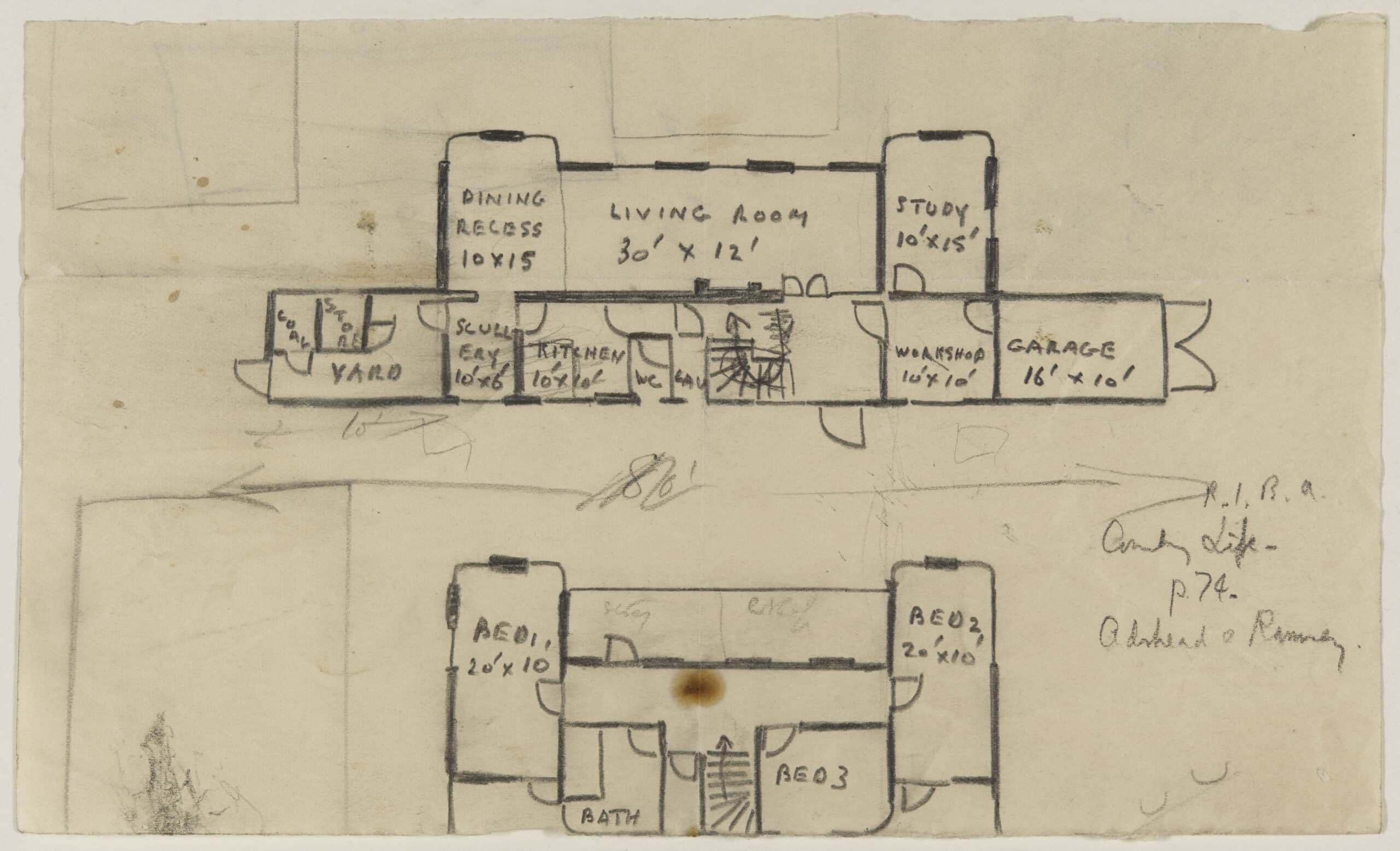

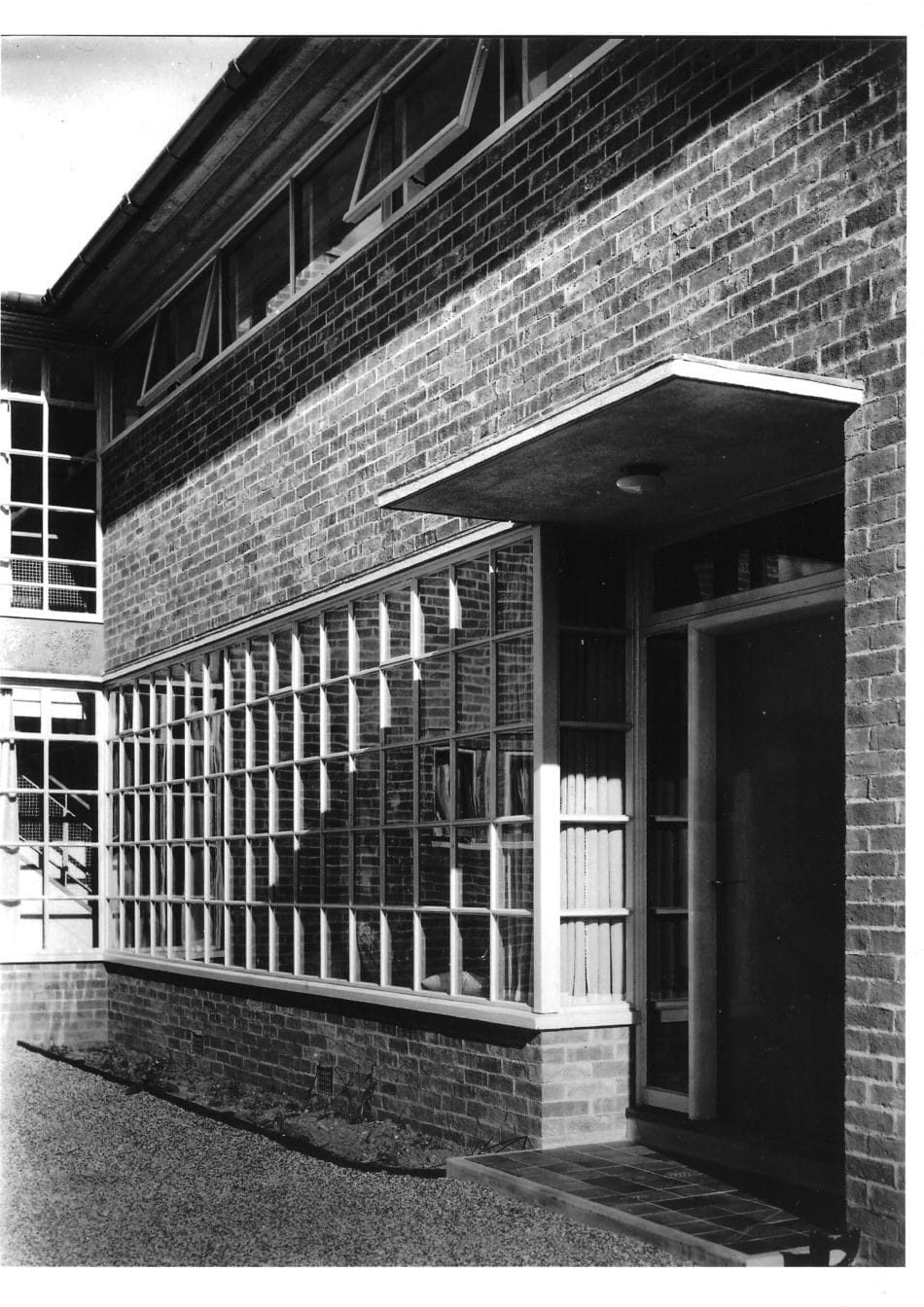

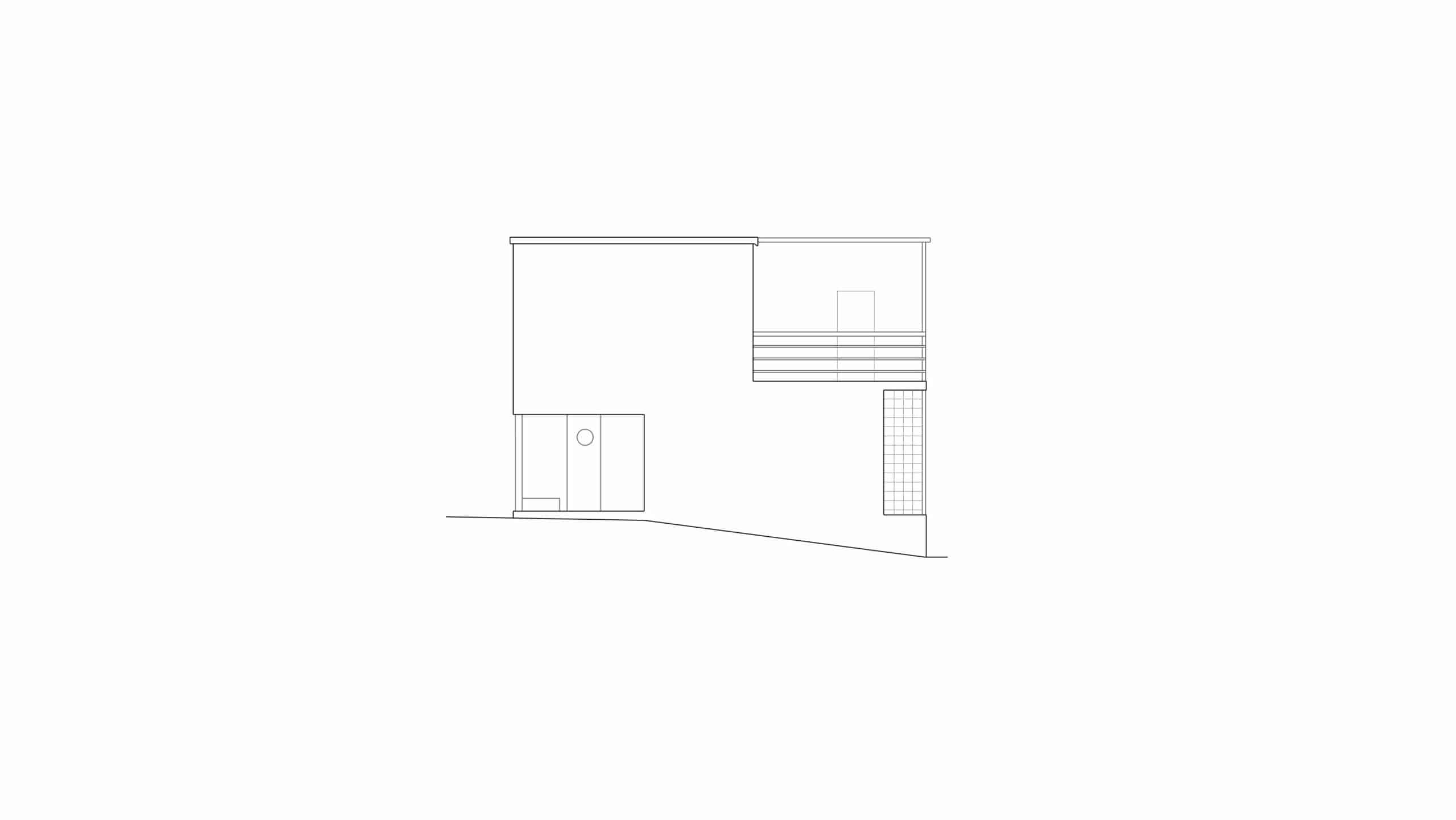

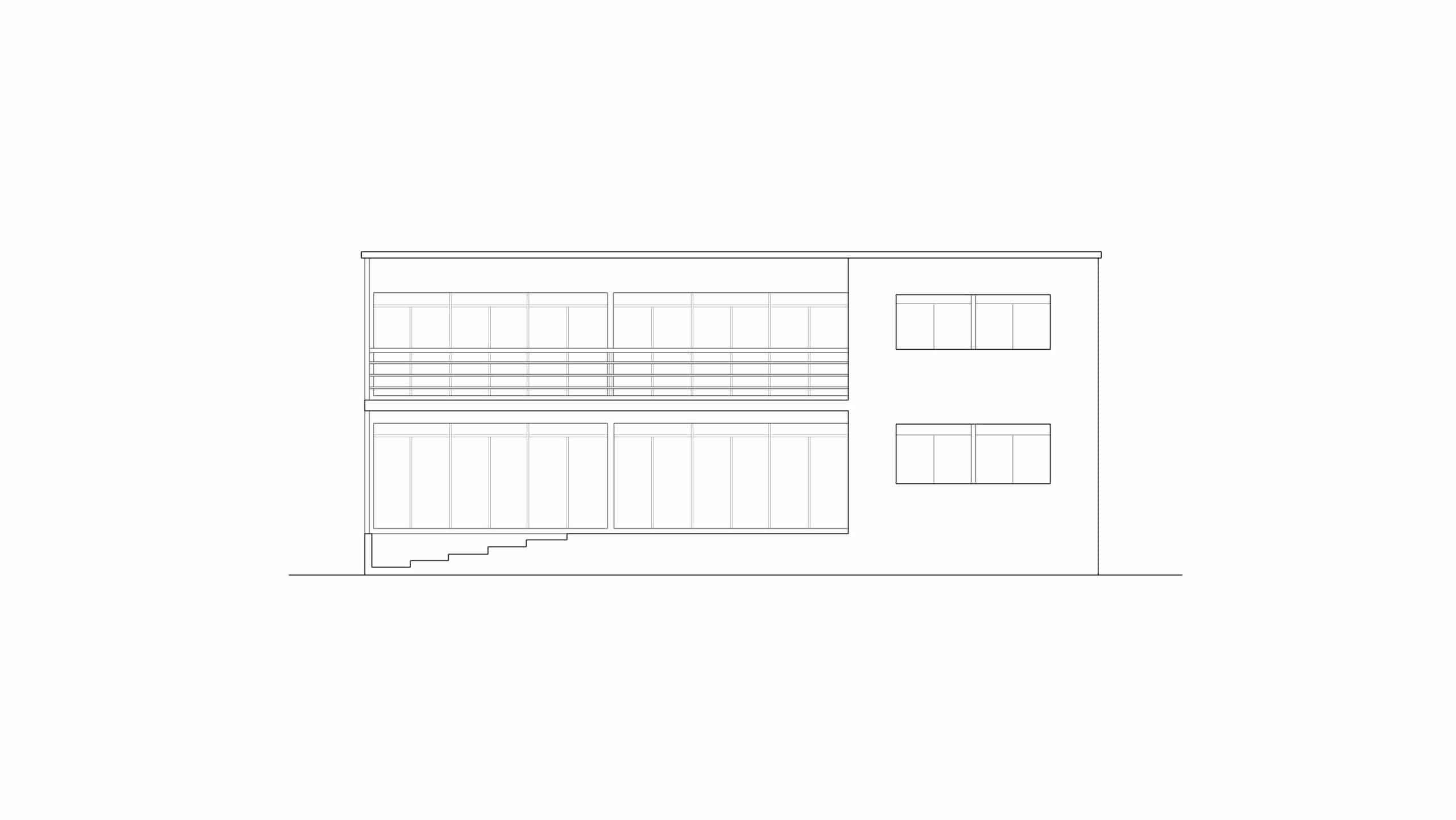

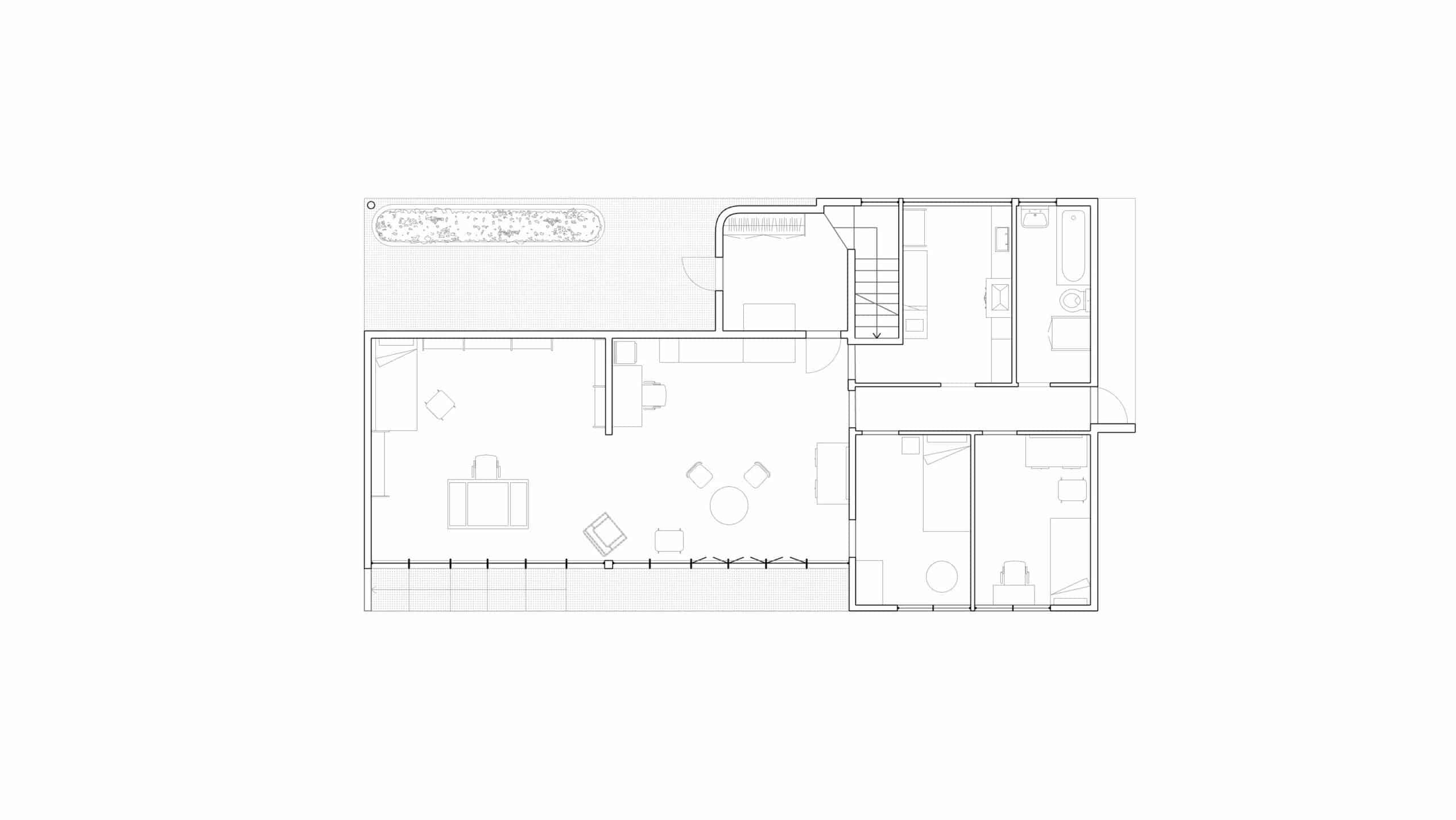

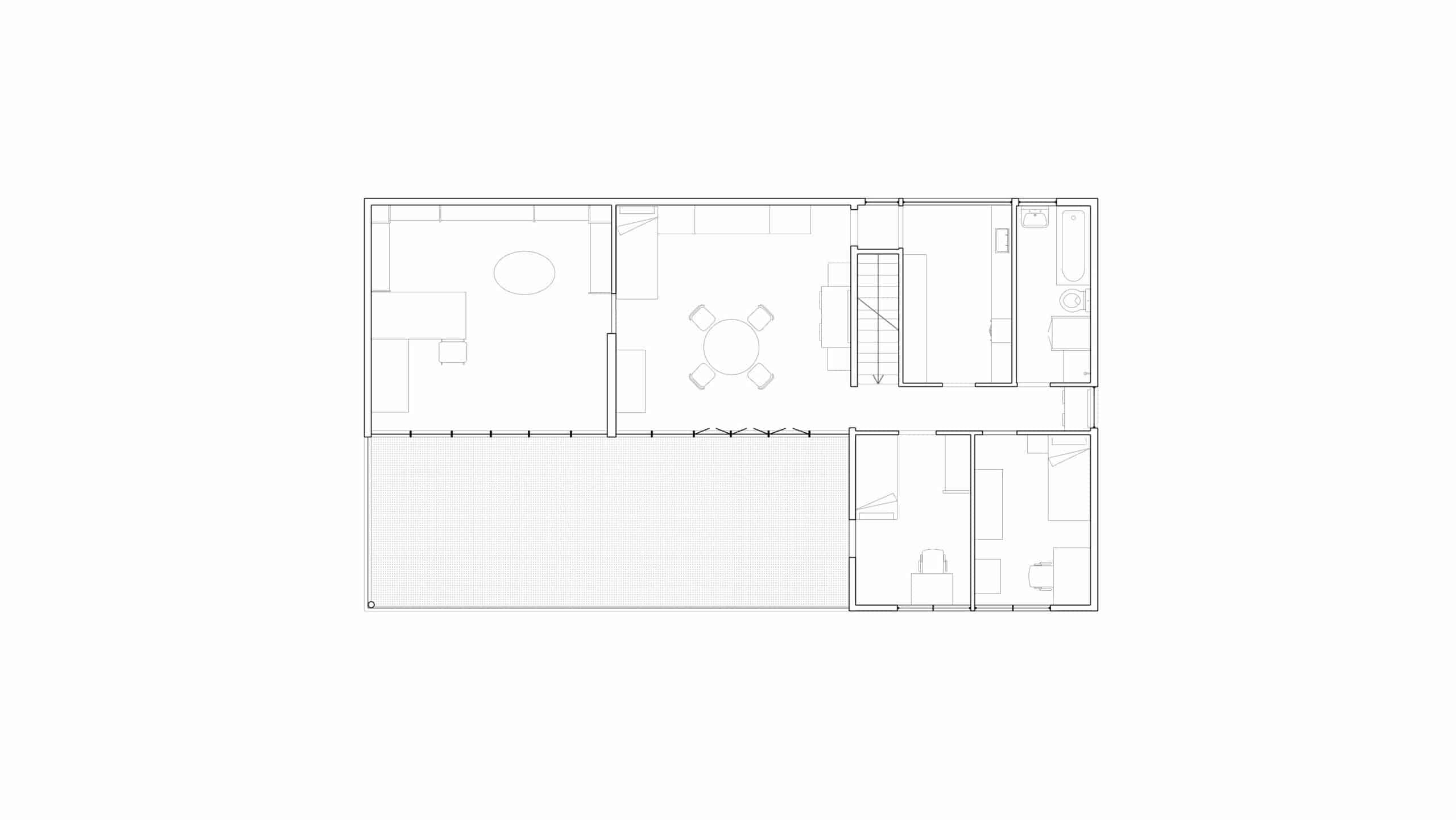

All three versions of Godfrey Samuel’s project provided two front doors. Earlier drawings place these side-by-side on the northern facade as if this were a semi-detached house. These versions have two identical sets of private accommodation laterally disposed in a strip facing the lane that ran along the top of the site, for sleeping, dining and washing, and a common-but-dividable space on the south side, which is always tagged ‘Book Room’ (not library) on the drawings, overlooking what was clearly a potentially beautiful garden with long views of the countryside. The section of these schemes is split to take advantage of the southwards facing slope, the first providing a 1.5-storey high living room in a section reminiscent of Wells Coates’ apartments at Queen Anne’s Gate; the second providing access to a large roof terrace from cell-like bedrooms.

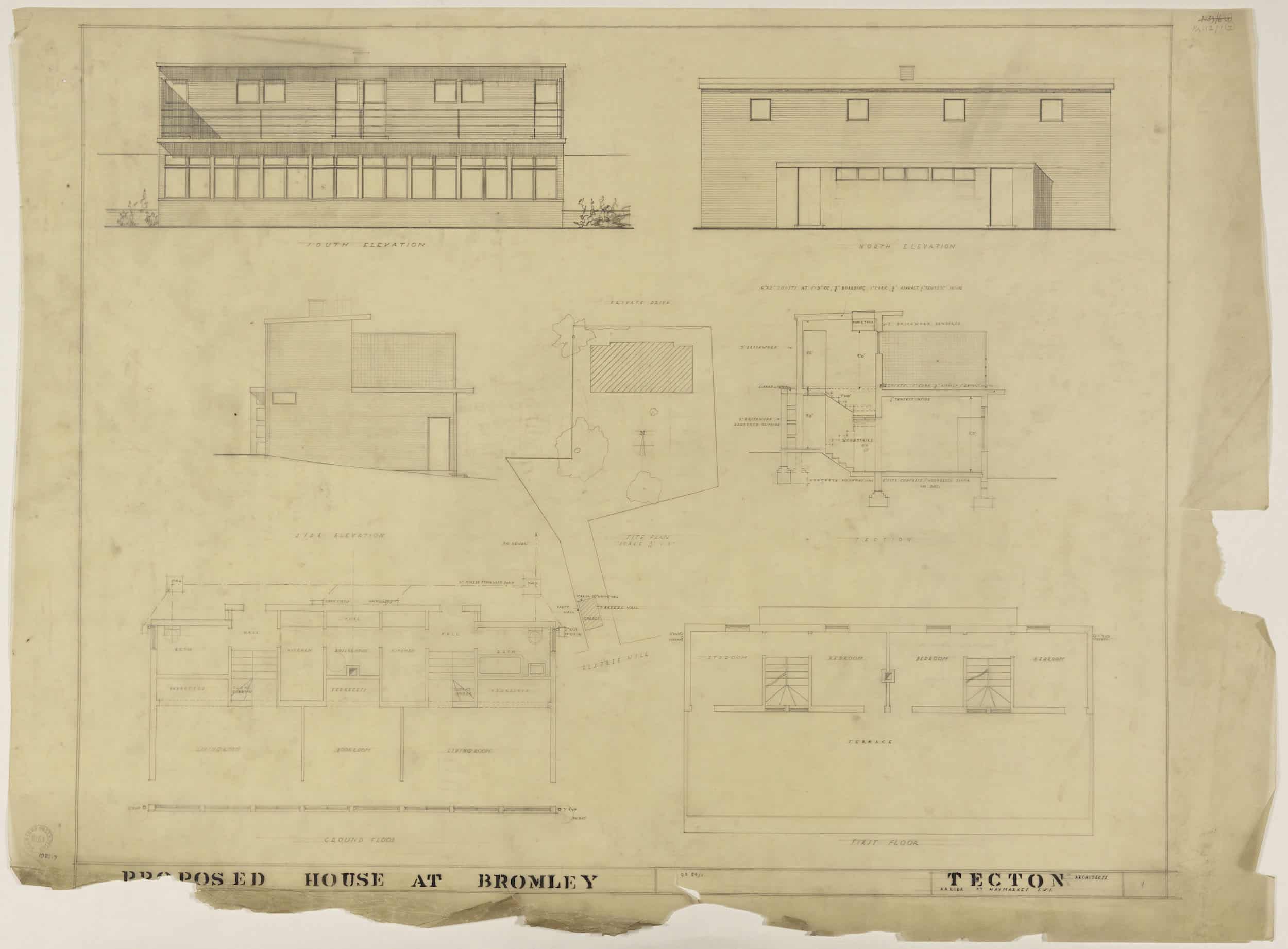

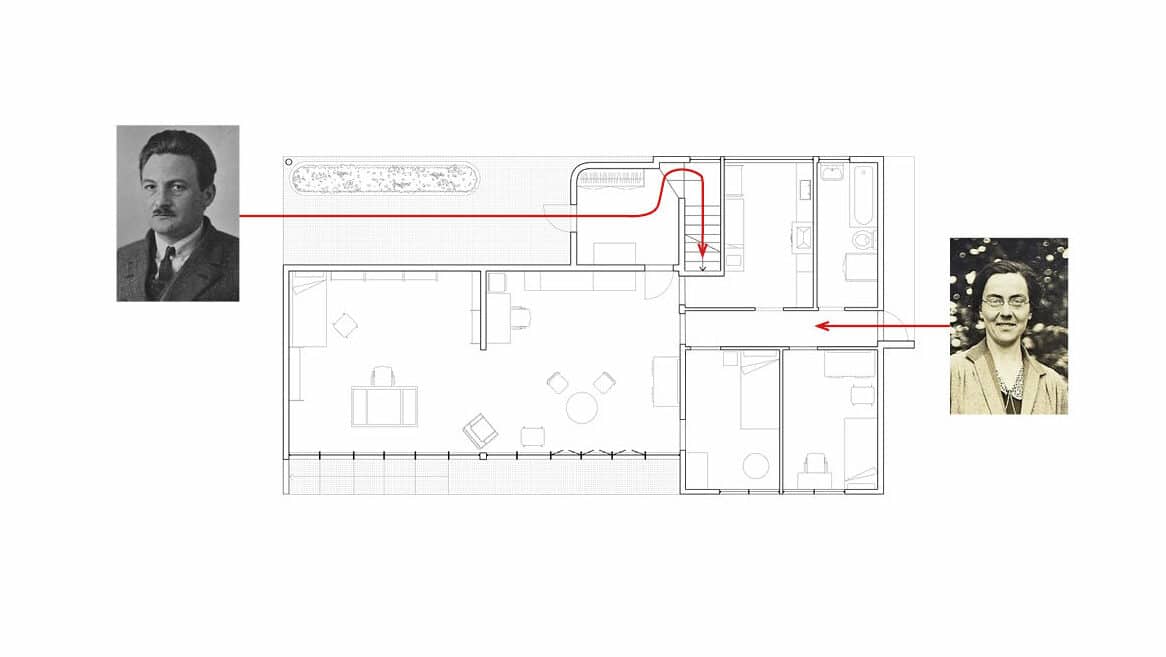

The third and final version of the house tips this organisation onto its side and is altogether more subtle. Horizontal in emphasis and more clearly inspired by continental models (and much more like Samuel’s later work, particularly his house for Ellis Waterhouse, Overshot Hall), it is two-storied with two separate – and labelled – entrances, one for Saxl and one for Bing.

Saxl would arrive from the west through a cut-back porch before mounting the stairs into his apartment on the first floor. Bing would enter from the east through a single door in an otherwise mute facade to her accommodation on the ground. Saxl was a gadgets man, loved cars and a garage is conspicuously placed at the edge of the site to the south, at the bottom of the garden facing Elstree Hill. Did they anticipate driving down from work in Westminster each day in a shared Riley, and taking separate paths up through the garden? Or was Saxl to drive and Bing take the train? No one now can say. Whatever: when they reached home, Saxl’s apartment lay over Bing’s, his sun terrace above hers.

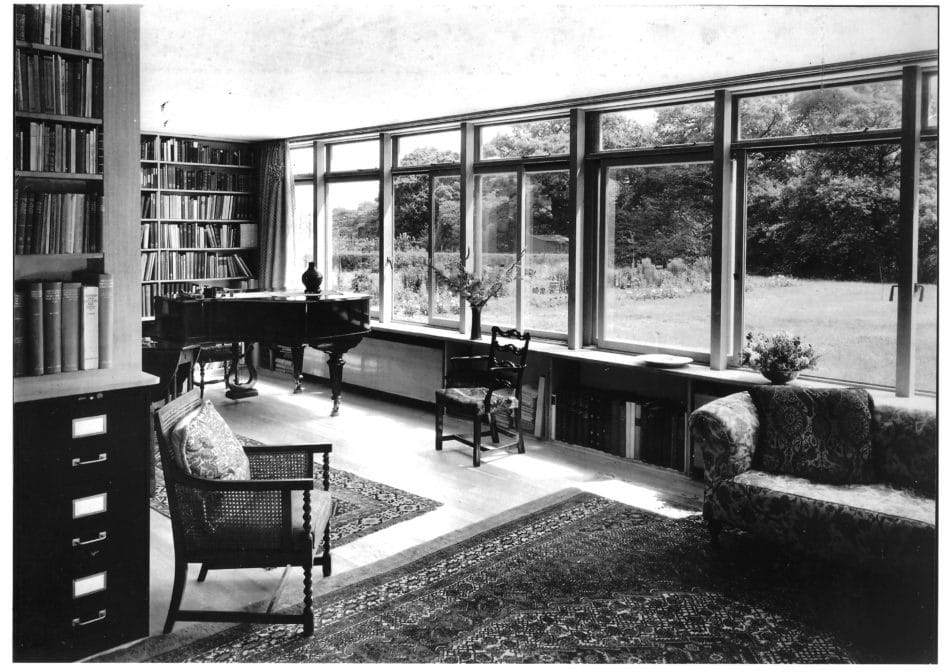

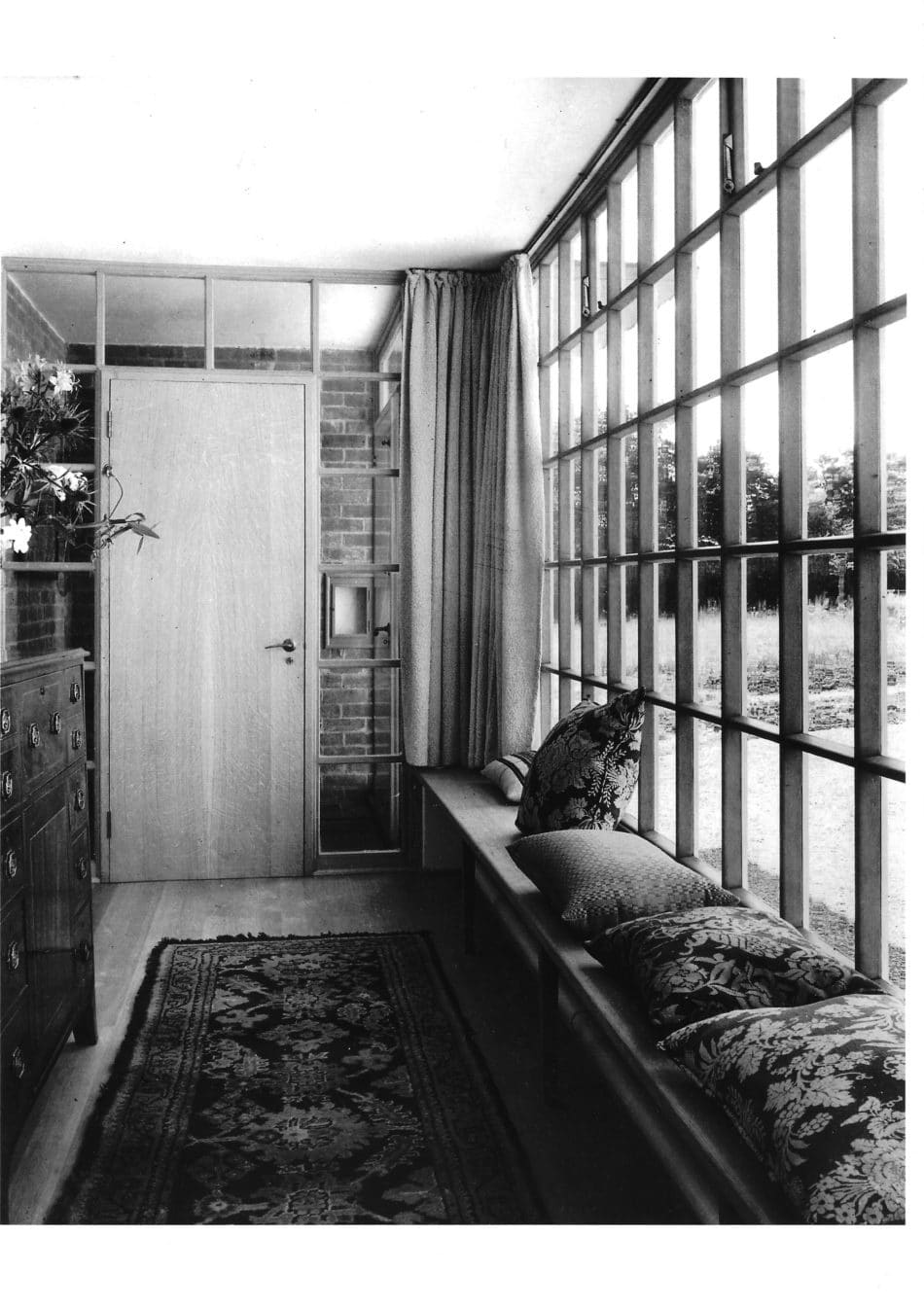

The garden front of the house is largely glazed, open to sun and air. Steel columns support the terrace on the first floor. The bedrooms on the first floor have direct access to Saxl’s external terrace, a popular arrangement in England during the 1930s, with its vogue for the continental-at-home, for fresh air and sleeping balconies. In the elevation, a wall of glass-block provides privacy. Some of the main functions are doubled as if this were two houses: two kitchens, two bathrooms, two dining rooms, and two book rooms; some are shared as if they were one: a furnace room (the subject of discussion in the letters and clearly very important) and a basement for storing ‘unwanted furniture’ (NB: Freud could be read both in the original German and in the early English translations by James Strachey and Alix Sargant Florence by 1934). Bing’s floor has a maid’s room and a guest room. Saxl has bedrooms for his daughter Hedwig (born 1914) and son Peter (born 1915; Samuel would later sponsor Peter’s naturalisation as a British citizen in 1939 and probably supported his successful application for a studentship at the Architectural Association). The plans make no declaration about the sleeping arrangements of the clients themselves. The house is ambiguous about the exact relationship of its occupants.

A coded system

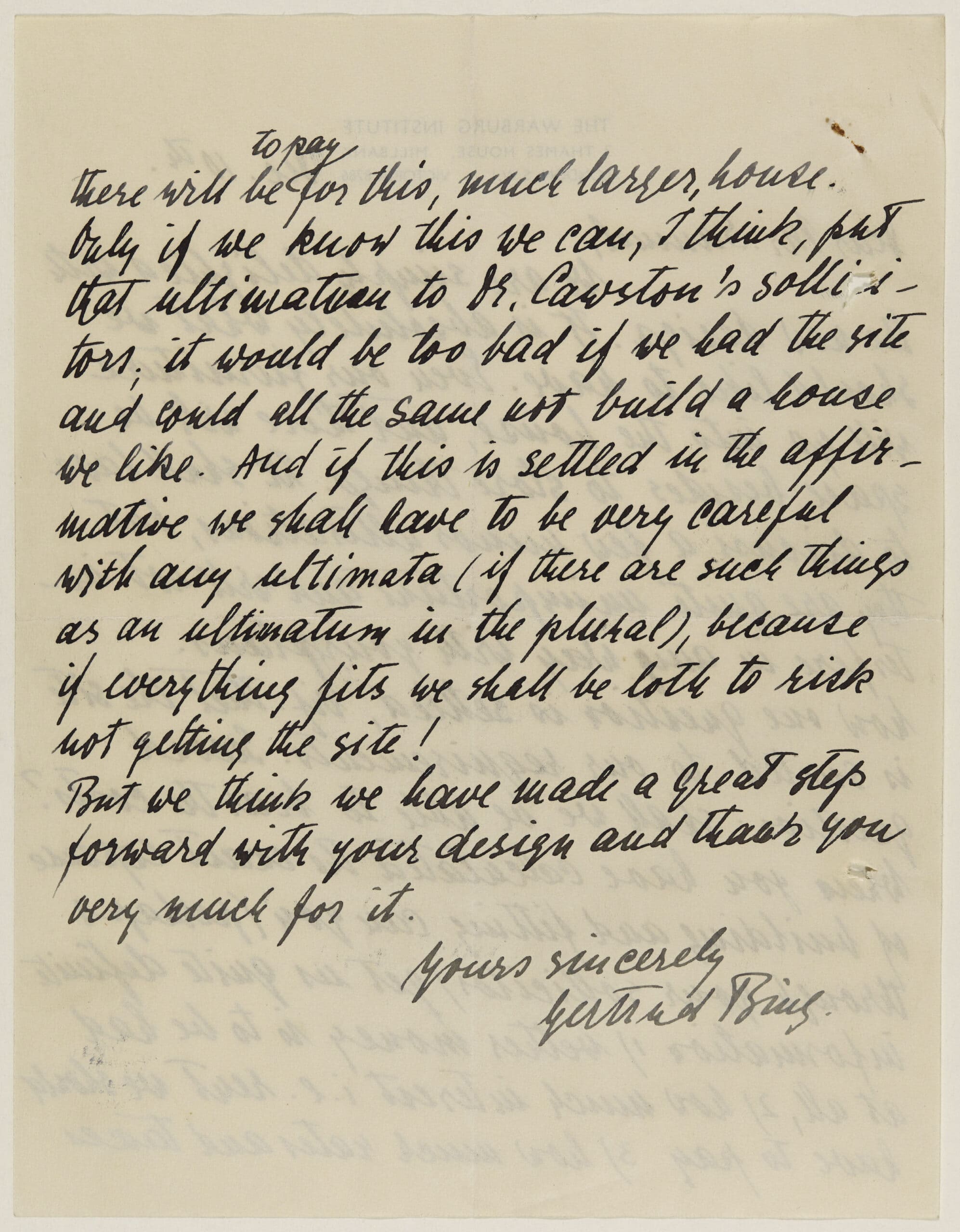

‘Dear Mr. Samuel,’ Bing wrote on December 10, 1934: ‘We are simply delighted with the new design. It is absolutely what we should like to have. Even our furniture will go into the house, and there will be space besides to store things.’

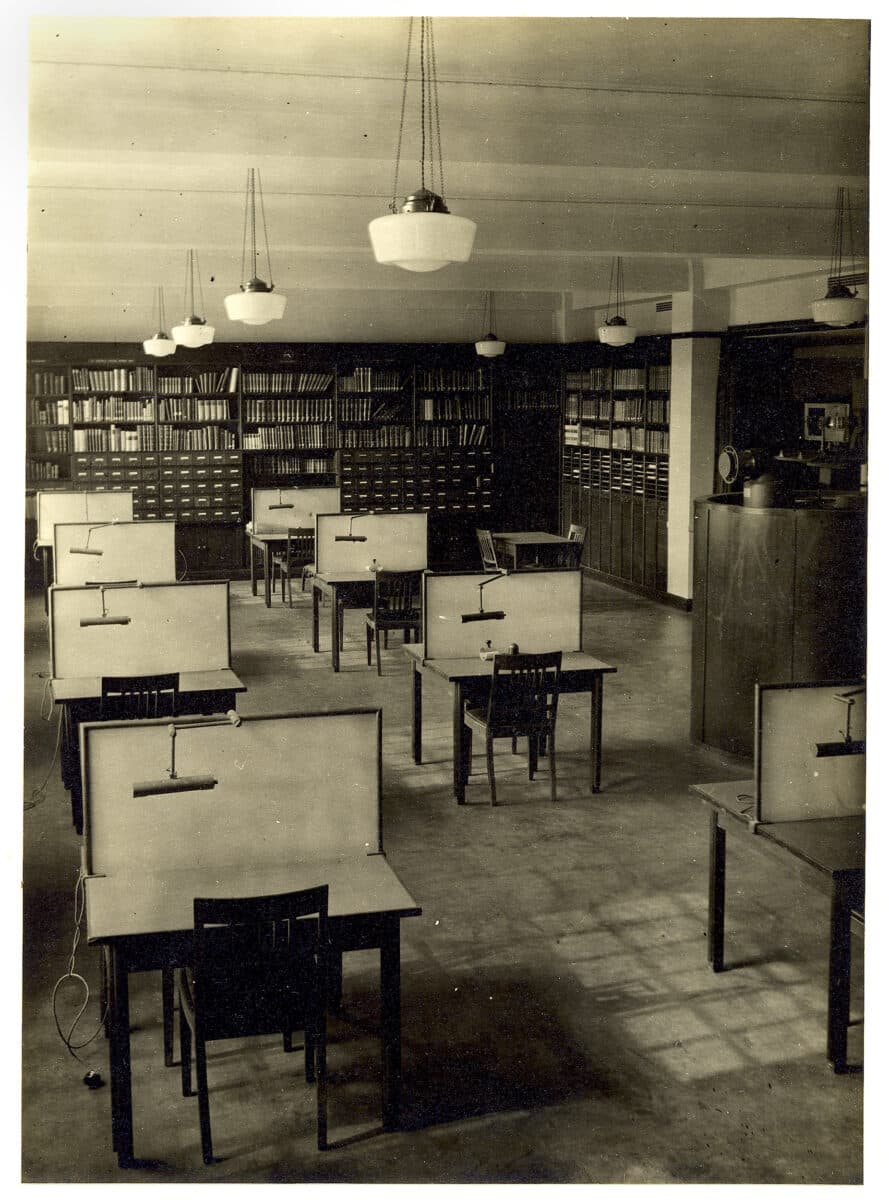

Bing was obsessed with furniture and furnishing. Posthumous descriptions by friends record an intimate connection between personal identity, furniture and establishment. For Donald Gordon, Bing seemed ‘always to have been behind a table…that desk in the tiny room at the Imperial Institute… the huge black post-Bauhaus desk in her room in Dulwich…’ [4] In Michael Baxandall’s recollection of the same house ‘Bing sat at the desk [in Saxl’s study] – oneself in a very German chair.’ [5] In some way this reliance on the mobility of furniture connected, in its turn to an obsession with gardens. In their later home ‘Bing spoke of Saxl’s elusiveness, his acceptance of the provisional, his wish to be free: …yet, and always yet, there was that garden designed and planted and cherished… a maturity that would take years to come…’. [6] This curious double quality Gordon summarised as articulating ‘here and now, place and time, being here, past precipitated in present.’ [7]

One can read both Bing’s obsessions – with the furniture of the house and the potential of the garden – in Godfrey Samuel’s plans. ‘I am returning the schedule of furniture … so that you can identify the pieces in the plan,’ Samuel wrote to Bing on January 11, 1935. There is ‘[m]ore room for furniture in the living room (but I think that it may be necessary for some of Dr Saxl’s furniture to be used by you)’. The schedule has not survived, but the plan for the project that surely accompanied this letter does (‘I am sending you a revised sketch scheme’), and on it the numerical sequence that identified each piece of furniture has been transcribed. From Bing and Saxl’s precise letters about furniture at the Warburg Institute, written at various periods, it seems certain that they would have supplied dimensions for each piece of furniture, and from an analysis of the number sequence in the plans it seems very likely that the schedule Bing had given Samuel had some kind of subject catalogue system within it. Bing had self-trained as a librarian as she became responsible for much of the work refining the cataloguing system for Warburg’s library. [8] Numbers 8, 9 and 11 on Samuel’s plan seem to refer to beds; 22–28 are chairs and tables and interestingly it looks as if Bing, in good German fashion, moved her gas cooking stove from Hamburg (it is marked number 15 on the plan), however unlikely this might seem. Half the furniture in her apartment is marked with a prefix ‘S’, and we guess these are items of ‘Dr Saxl’s furniture to be used by you’. In Samuel’s drawing everything is drawn as simple squares and rectangles outlining bookshelves, tables, chairs, etc. Presumably these chattels arrived in London with the library and its furniture, on board the SS Hermia in one of the two shipments organised by the Institute in Hamburg, when they sent the bulk of Warburg’s collection to London as a three-year loan in December 1933.

Destiny

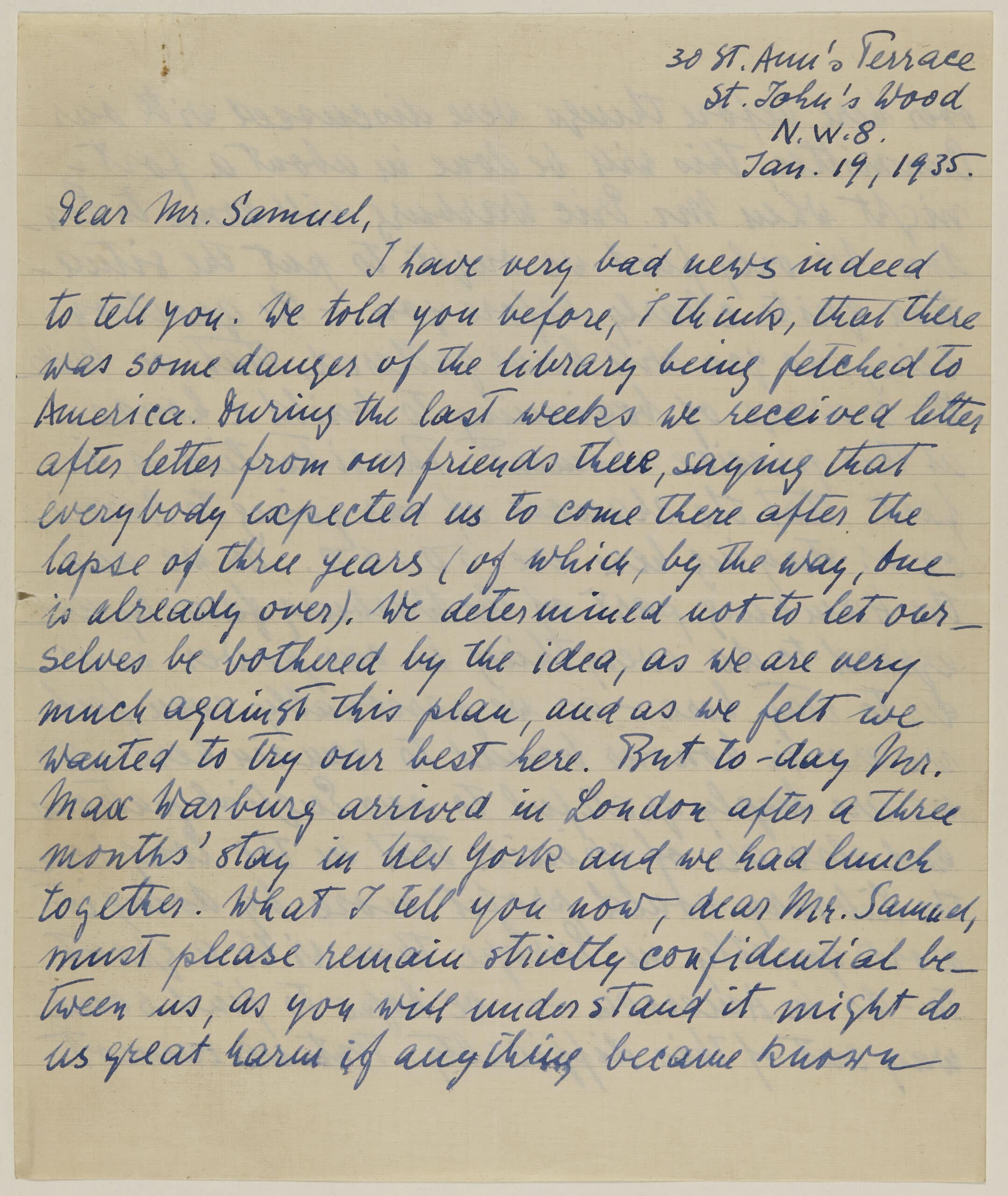

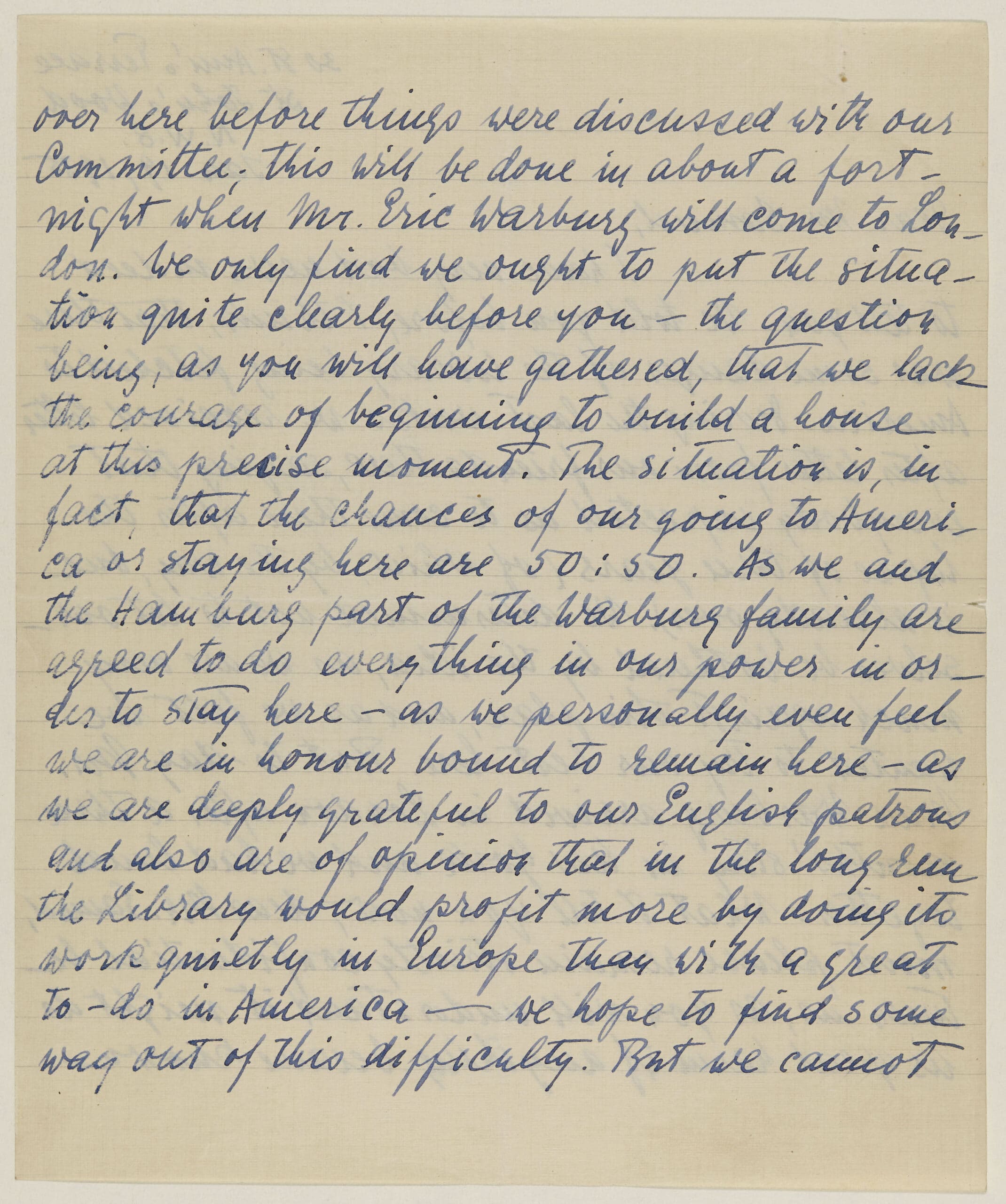

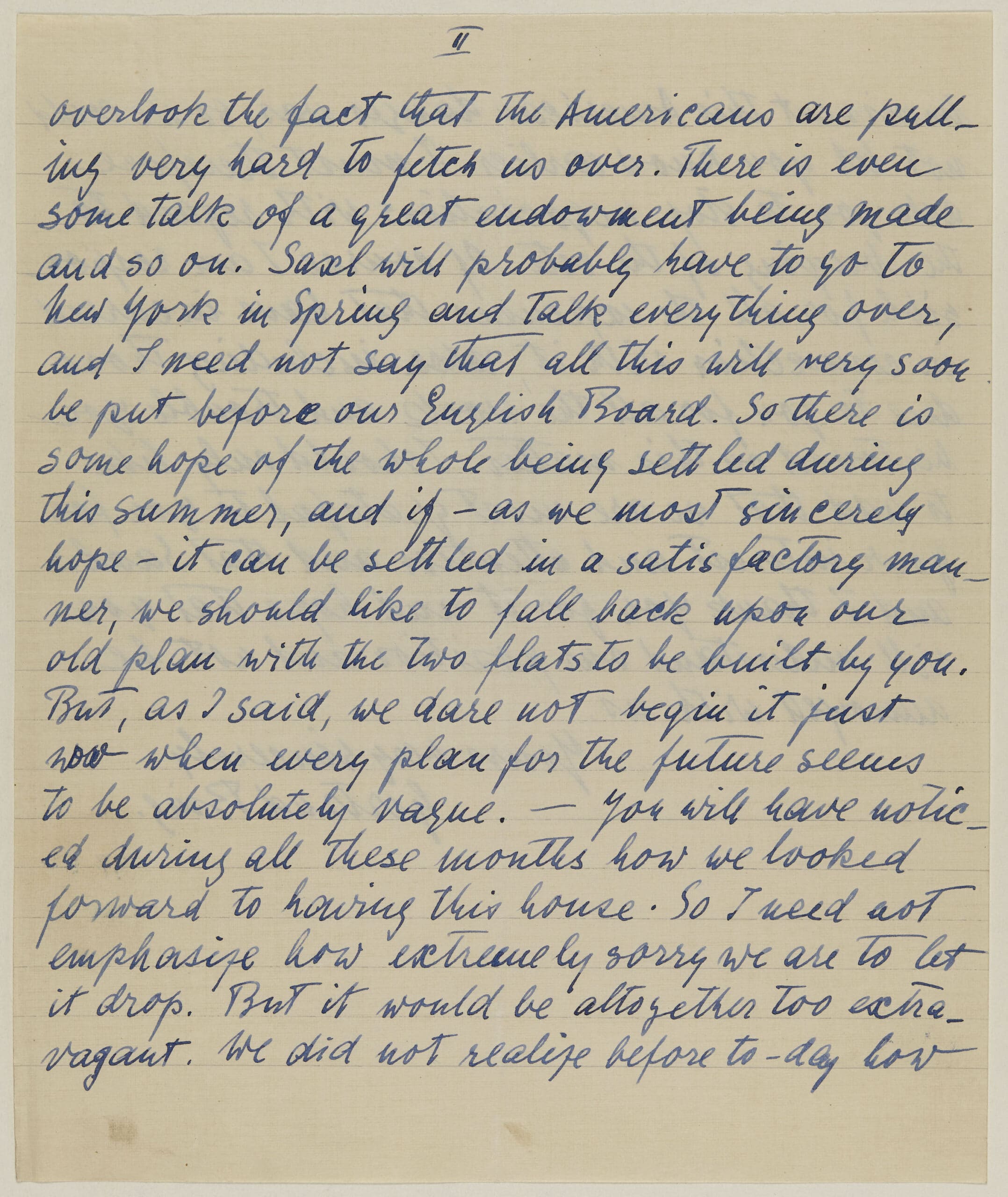

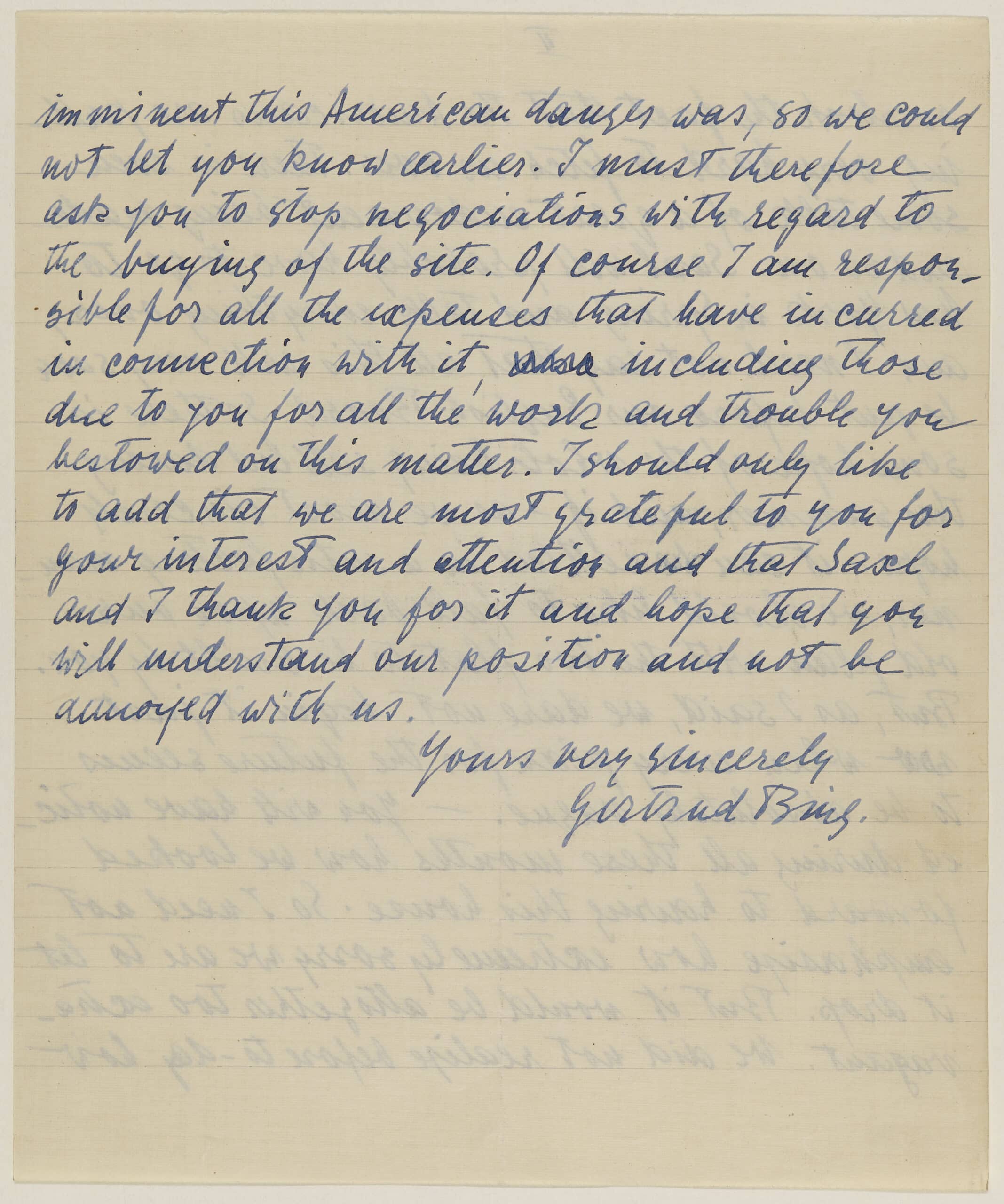

Godfrey Samuel’s composition is time-typical. Yet, hidden in his drawings lies a compelling story of two clients’ collaboration with an architect, filled with codes and patterns. The Cottage at Bromley was designed while the Warburg Institute was occupying its brand new Tecton interiors at Thames House, and at a point when it was still unclear whether the library would remain in London, or relocate to the United States. On 14 January 1935, just days after Samuel has presented the ‘scheme that I think solves all the problems raised’, Bing writes to him with ‘very bad news’. She has had lunch with Max Warburg who has arrived the same day from New York. All is in flux; the future of the library and of Bing and Saxl’s London life uncertain. The chances as to whether the library stays or moves are, she says ‘50:50’. Although Bing and Saxl ‘wanted to try our best here’, ‘the Americans are pulling very hard to fetch us over’. It appears as if the matter might be solved during the coming summer, but they ‘lack the courage of beginning to build a house at this precise moment’. To proceed with the house would be ‘altogether too extravagant’. With much regret she asks Samuel to terminate the negations on purchasing the site.

Below: Correspondence between Godfrey Samuel and Gertrud Bing. RIBA Collections. Godfrey Samuel Papers, Series 2: Projects undertaken by Samuel, 1933–1938.

© The Estate of Gertrud Bing (courtesy of the Warburg Institute Archive)

© The Estate of Gertrud Bing (courtesy of the Warburg Institute Archive)

© The Estate of Gertrud Bing (courtesy of the Warburg Institute Archive)

Text, drawings and models by Pernille Ahlgren.

Notes

- Letters from Gertrud Bing to Godfrey Samuel, September 29 1934, December 10 1934, January 14 1935. Letter from Godfrey Samuel to Gertrud Bing, January 11 1935. RIBA Drawings Collection. Godfrey Samuel Papers, Series 2: Projects undertaken by Samuel, 1933–1938.

- Elizabeth Sears, ‘The Warburg Institute, 1933–1944. A precarious experiment in international collaboration,’ Art Libraries Journal 38/4, 2013, 7-15. Our very warm thanks to Elizabeth Sears for commenting on this article, and for clarifying numerous elusive details in Saxl’ and Bing’s biographies.

- Recounted by Anne Marie Meyer (secretary to the Institute who came with it from Hamburg in 1933, was very close to Bing and who was charged with destroying her papers) to Fritz Saxl’s biographer Dorothea McEwan, and in turn to us by Claudia Wedepohl of the WIA. Our thanks to all for this information.

- Donald Gordon, ‘In memoriam Gertrud Bing,’ in Ernst Gombrich (ed.), In memoriam. Gertrud Bing: 1892–1964, London 1965, 11. Reprinted in Monica Centanni and Daniela Sacco (eds.), ‘Gertrud Bing. Erede di Warburg’, La Rivista di Engramma 177, (November 2020), 132. On Bing’s contribution, character and customs see in addition Laura Tack, The fortune of Gertrud Bing. A fragmented memoire of a phantom-like muse (Leuven: Peeters, 2020).

- Michael Baxandall, Episodes. A Memory Book (London: Frances Lincoln, 2010), 114.

- Gordon, ‘In memoriam’, 144.

- Ibid., 152.

- Tim Ainsworth Anstey, ‘Moving memory: the buildings of the Warburg Institute’, Kunst og Kultur 3/2020 (vol 103), https://www.idunn.no/kk/2020/03/moving_memory_the_buildings_of_the_warburg_institute