The Design Legacy of Tamar de Shalit and Arthur Goldreich

After visiting the Tamart studio in Hoxton to see the collection of drawings by Tamar de Shalit and Arthur Goldreich, and the growing collection of furniture based on their designs, the editors asked Amos Goldreich to write this illustrated account of his parents’ remarkable lives both in South Africa and Israel.

My mother, Tamar de Shalit, was born in Tel Aviv in 1932. Seeking to expand her creative horizons, she moved to London in 1951 to study interior architecture at the Central School of Arts and Crafts (now known as Central Saint Martins), a decision that would prove pivotal not only for her professional development but also for her personal life.

My father, Arthur Goldreich, was born in South Africa in 1929. Driven by idealistic visions of contributing to the physical and ideological construction of the newly formed state of Israel, he began his architectural education there. His educational journey later took him back to South Africa in the 1950s before he too found himself in London at the Central School. It was amid the stimulating academic environment of London that my parents’ paths converged, beginning both a creative partnership and lifelong personal bond.

After returning to Israel in the late 1950s, my mother joined Nachum Maron’s Israel Product Design Office (IPDO), where she quickly established herself as a designer of remarkable versatility. Her career reached an early milestone when she was entrusted with designing the interior architecture for the courtroom of Adolf Eichmann’s trial in Jerusalem in 1961—a project of immense historical significance that required careful consideration of both practical functionality and symbolic weight. The success of this project led to numerous commissions for ministerial and civic design projects.

My father’s career, meanwhile, flourished across multiple creative domains. His artistic talent was recognised in international exhibitions, while his theatrical sensibilities found expression in set designs and costumes for major theatre productions. Never one to separate aesthetics from ethics, his deep commitment to social justice manifested in vocal anti-apartheid activism, culminating in his arrest alongside Nelson Mandela in 1963.

What unified my parents’ work was a shared commitment to modernist principles, adapted to the unique cultural and climatic context of the place they worked in. My mother’s multidisciplinary approach—spanning interiors, furniture, lighting, textiles, fashion, and jewellery—reflected her approach to ‘total design’, where good design should be holistic and consider how different elements interact within a space. Her contribution to Israeli modernist and brutalist styles came through projects that balanced international design currents with local materials, needs and aesthetic sensibilities.

My father’s influence extended beyond his architectural projects, through his role as founder of the Department of Environmental and Industrial Design at the Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem. As an educator, he became one of Israel’s most influential professors of design and architecture, distinguished by his insistence on integrating critical-political discourse into design education. He believed designers should question not just how things look, but what they mean and whose interests they serve—a philosophy that influenced how a generation of Israeli designers approached their craft.

Though each maintained distinct professional identities, my parents’ collaborative work represented a unique synthesis of their complementary strengths. My father brought conceptual rigour and political consciousness to their joint projects, while my mother contributed meticulous attention to detail and a profound understanding of how spaces shape human experience.

Their legacy lives on not just in the physical spaces and objects they created, but in how they helped define a distinctly Israeli design language during a formative period in the country’s cultural history. Their work demonstrated that design could be simultaneously international in its influences and deeply rooted in the local context—a lesson that remains relevant in our increasingly globalised world.

As their son, I witnessed firsthand how their creative process was never confined to working hours, but permeated our family life, turning everyday experiences into opportunities for aesthetic consideration and critical reflection. Their careers showed me that design is not merely about making beautiful things, but about shaping how people experience and understand their world.

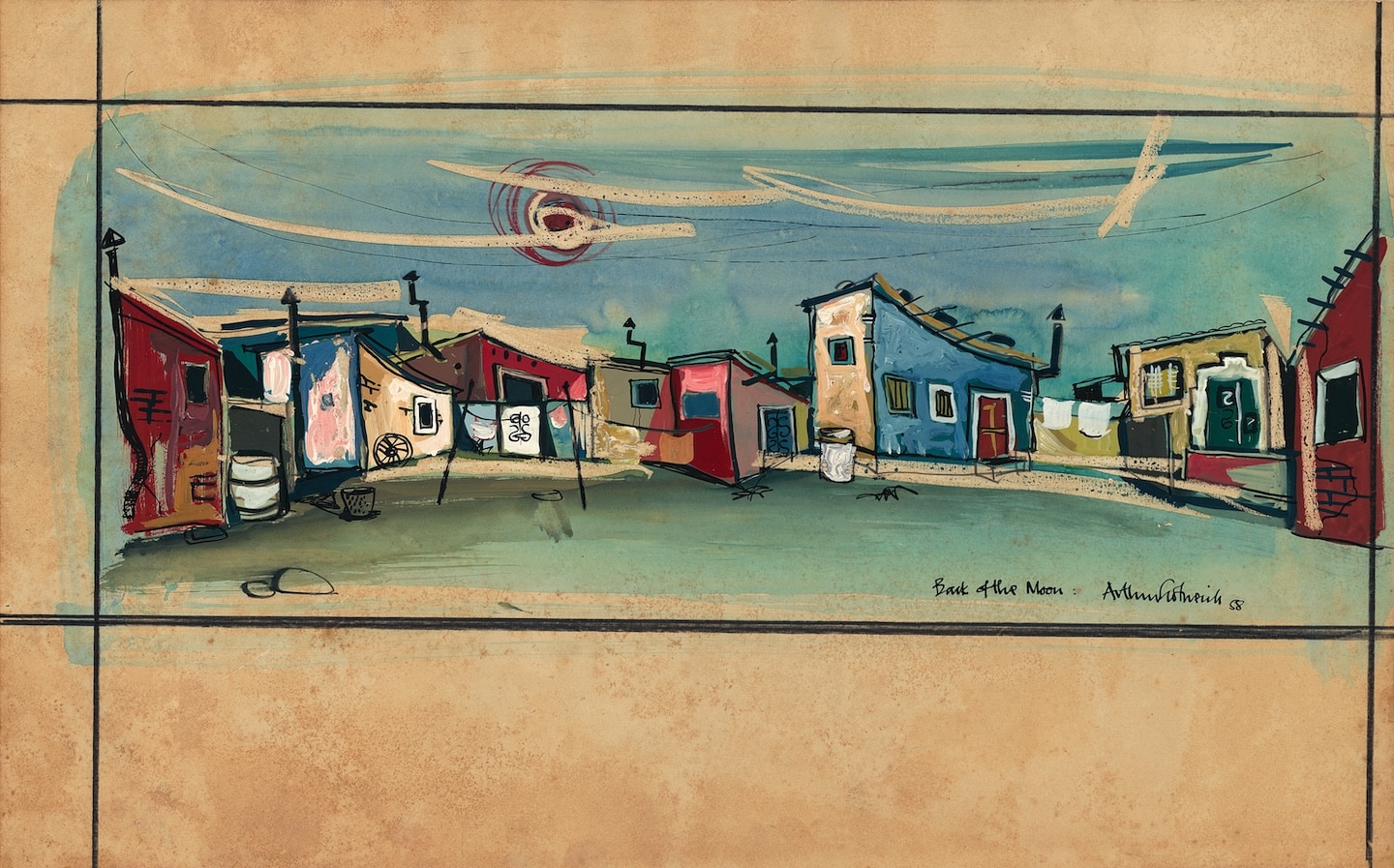

Stage set design for King Kong Jazz Opera (1958)

The jazz opera King Kong, staged in Johannesburg in 1959, was a groundbreaking production: 63 black and white performers shared a single stage and performed to a mixed audience, openly challenging segregation laws, while presenting modern black urbanism as an alternative to exotic tribal imagery. The show featured the incredible vocals of Miriam Makeba, who was just on the cusp of an internationally acclaimed career. With music composed by Todd Matshikiza and lyrics by Pat Williams, its authentic portrayal of township life and underlying themes of racial injustice resonated deeply with diverse audiences, combining entertainment with a powerful social statement during a dark period in South African history. The sets and costumes were designed by the 30-year-old Arthur Goldreich—his first major stage commission. His modernist visual language, inspired by Drum magazine, shattered stereotypes and cemented his reputation as a leading South African artist. In 1961 it was performed at the Princes Theatre in London. The musical’s success broadened Goldreich’s exposure, but also sharpened his ideological consciousness. Within about two years, he joined uMkhonto weSizwe, moved to Liliesleaf Farm and secretly concealed Nelson Mandela under the guise of a farmhand, under the alias ‘David Motsamayi’.

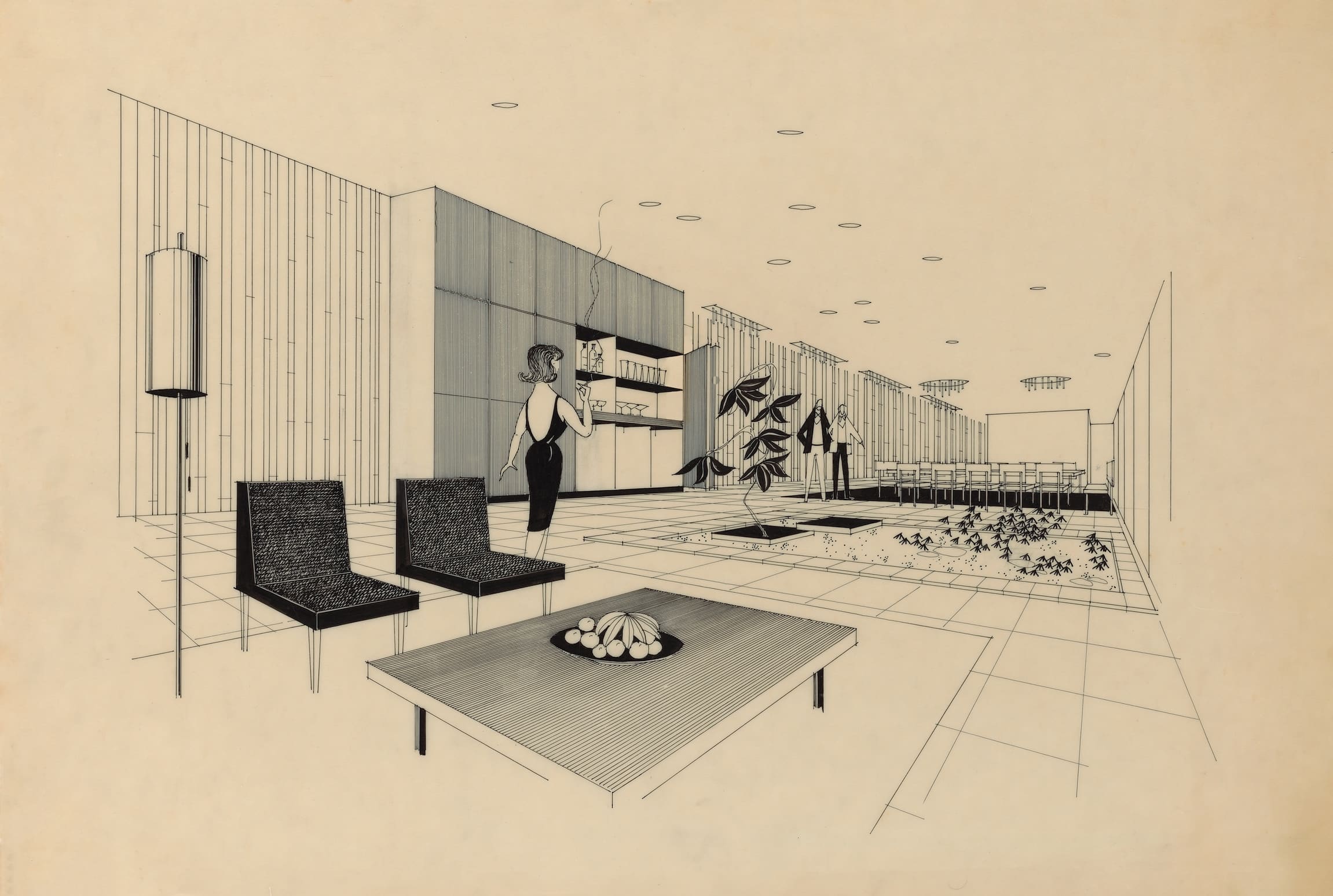

Penthouse for Sir Charles Clore (1963–64)

Sir Charles Clore’s penthouse (1963–64) at the Weizmann Institute marked Tamar de Shalit’s breakthrough as an independent designer. She received an extraordinary commission from the British philanthropist: to ‘design everything.’ She created or selected all elements—from built-in furnishings to tableware—with funding for European sourcing trips, as Israel lacked manufacturing capacity at that time. The project embodied the approach of ‘total design’, blending modernist functionalism with understated luxury. De Shalit introduced signature elements that would define her future work: space-saving integrated units and, most notably, a low chair-lounger that was widely used in many projects, despite the manufacturer’s initial scepticism. Design communication was paramount as Clore remained in the UK while the project progressed in Israel. Detailed drawings and interior perspectives bridged this distance. The penthouse established de Shalit as a designer of choice for prestigious projects, demonstrating her ability to articulate a clean, ergonomic modernism rooted in an emerging Israeli aesthetic.

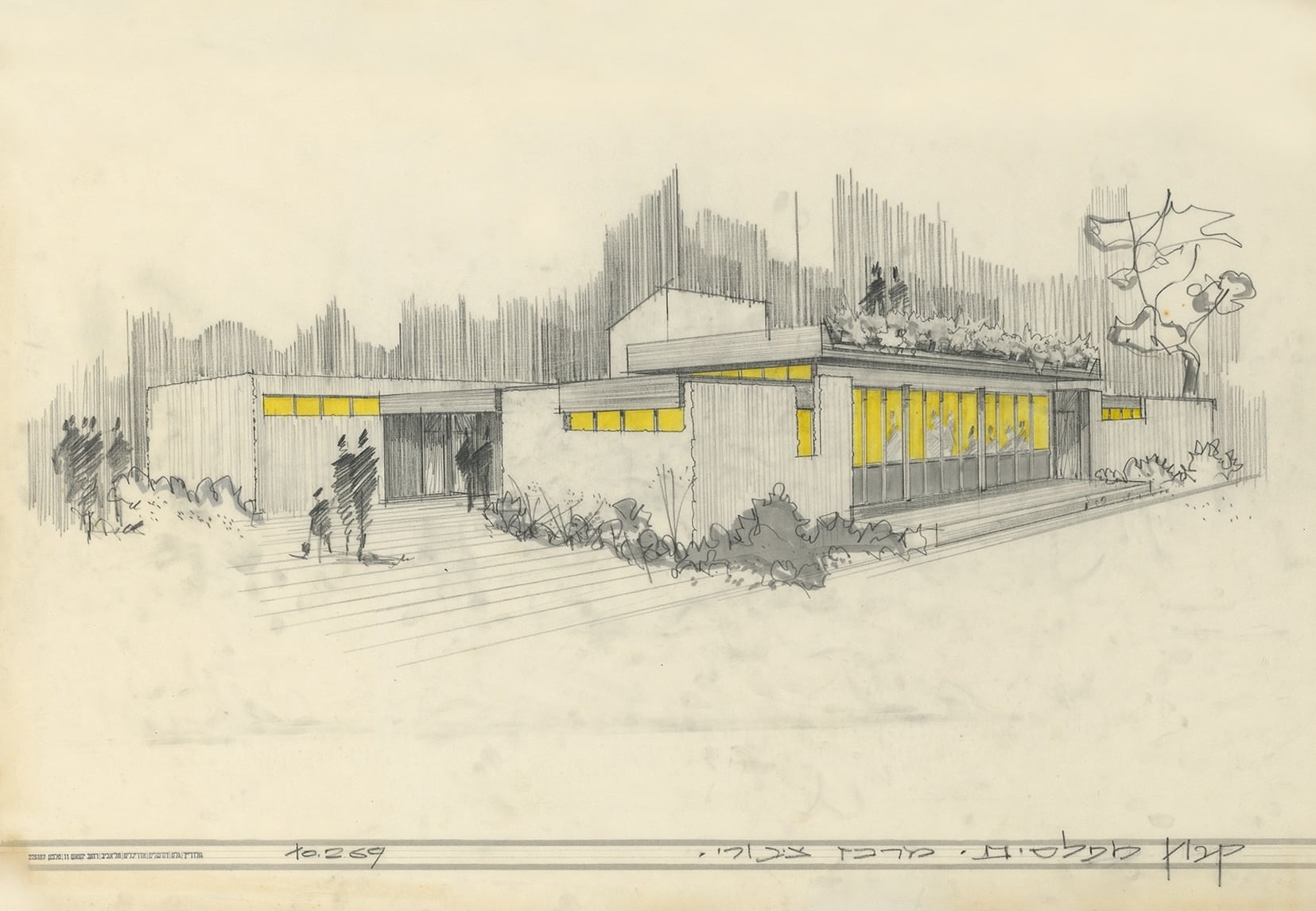

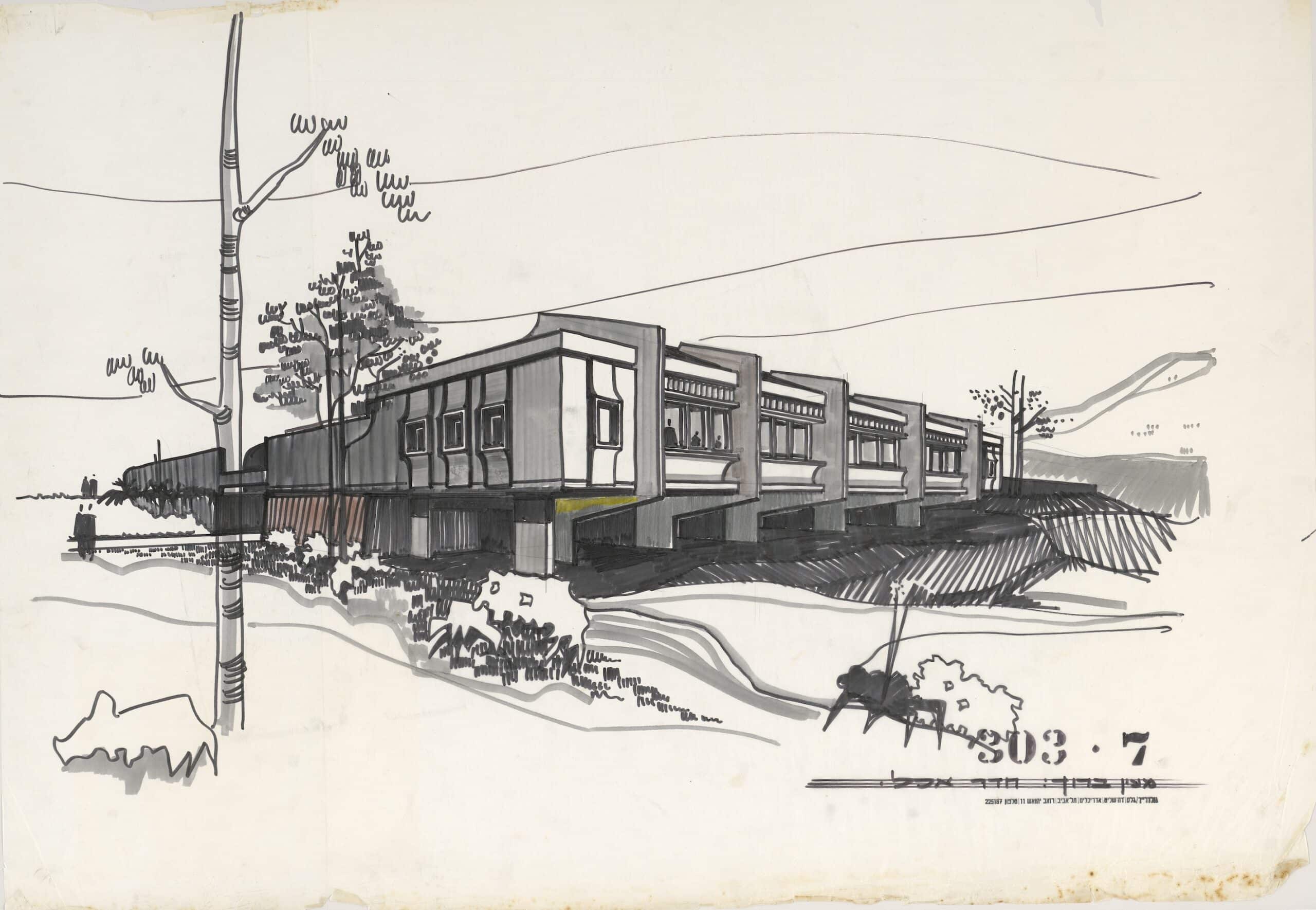

Community centre, Kibbutz Mefalsim (1967–73)

When Arthur Goldreich returned to Israel in 1964, after escaping from South Africa, he sought to forge a new professional identity. In 1967/68 he received an invitation from Kibbutz Mefalsim to design Beit Kitron. The first community centre he and Tamar de Shalit had been invited to create in a kibbutz: this marked a shift from dining-hall buildings to communal cultural spaces. The project accompanied him for almost a decade: from early design explorations in April 1973 to its inauguration in 1976. Work at Mefalsim unfolded through a series of plans, sections and façade sketches that Goldreich viewed as a research tool. Through this method—involving iterative drawing, testing and formal abstraction—he explored architectural solutions whilst developing ideas that became central to his teaching at Bezalel. These conceptual approaches materialised at Mefalsim in exposed concrete, timber panels and modernist swathes of colour. Beit Kitron’s wide windows and recessed glass doors created physical and symbolic transparency between the interior and exterior, responding to the collectivist values of the kibbutz movement. The arrangement of three wings around a common forecourt reflected Goldreich’s conviction that a democratic community needs an open stage.

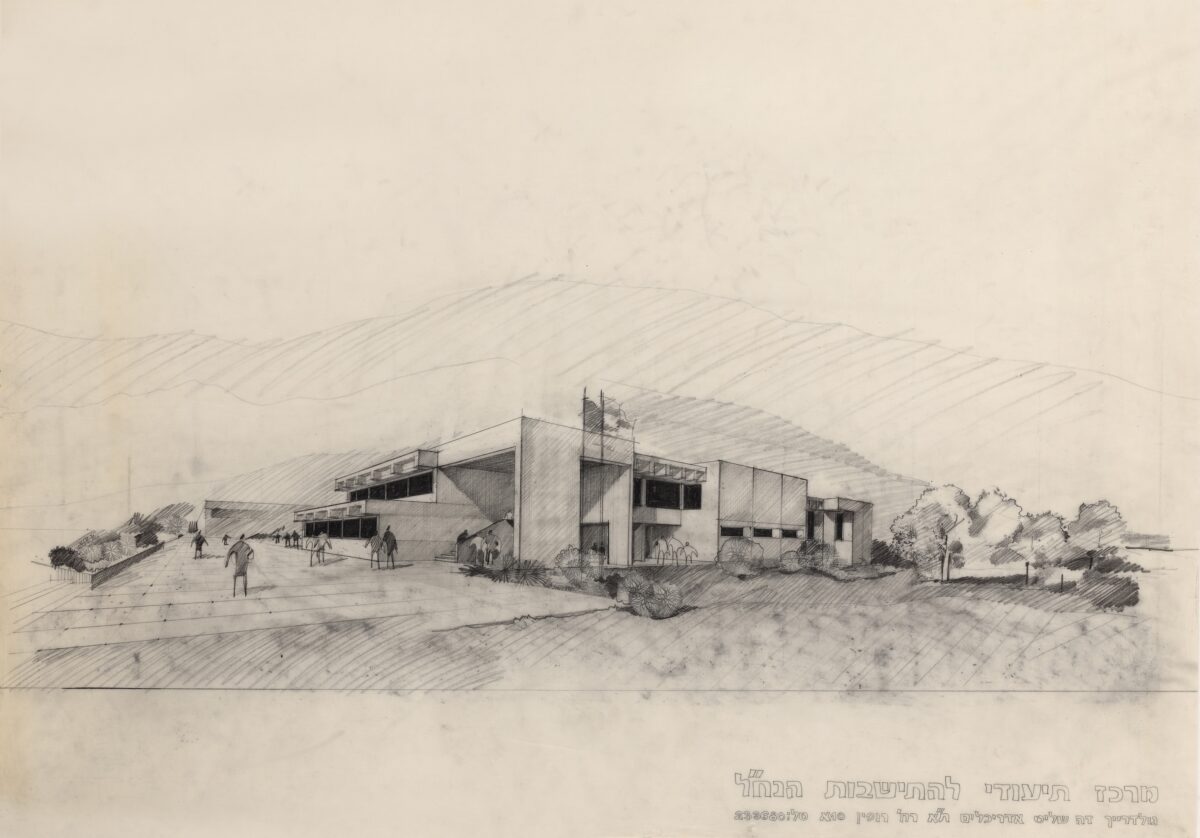

Nahal Settlement Documentation Centre (1970s)

The centre was conceived in the early 1970s to commemorate Kibbutz Nahal Oz (founded in 1951) as Israel’s first Nahal (military youth organisation). Arthur Goldreich and Tamar de Shalit designed a multi-stage complex—comprising a research centre, archive, members’ club and memorial around a communal forecourt—though planned additions were later abandoned due to funding constraints. The commission came during Goldreich’s ‘kibbutz phase’ following his 1964 return to Israel. After designing numerous dining halls that gave the kibbutz movement a context-sensitive modernist language, the Nahal Oz project signalled his transition towards institutions of memory and identity.

Dining Hall, Kibbutz Ma’ayan Baruch (1968)

The dining hall at Ma’ayan Baruch was designed in the late 1960s by Arthur Goldreich and Tamar de Shalit, early in their partnership that would later yield a series of public buildings in other kibbutzim. The initial scheme was drawn up in 1968, but the project was eventually taken over by the Kibbutz Movement’s planning department, and the building was inaugurated in July 1975. The original plan featured a flexible mass-structure composition, dividing the building into separate volumes, linked by bold beams and columns projecting above the roof line, allowing future extensions without disturbing the core arrangement. Proximity to the Lebanese border dictated two contrasting façades: a sealed, fortified northern face and an open southern elevation with broad windows overlooking the fertile Hula Valley. The scheme integrated a multi-purpose communal space, including a post office, telephone kiosk and notice-board in a central foyer, conceived as an ‘indoor square’ where the kibbutz’s paths converge. For Goldreich, the commission marked a symbolic return to the kibbutz where he had been a founding member in 1948.

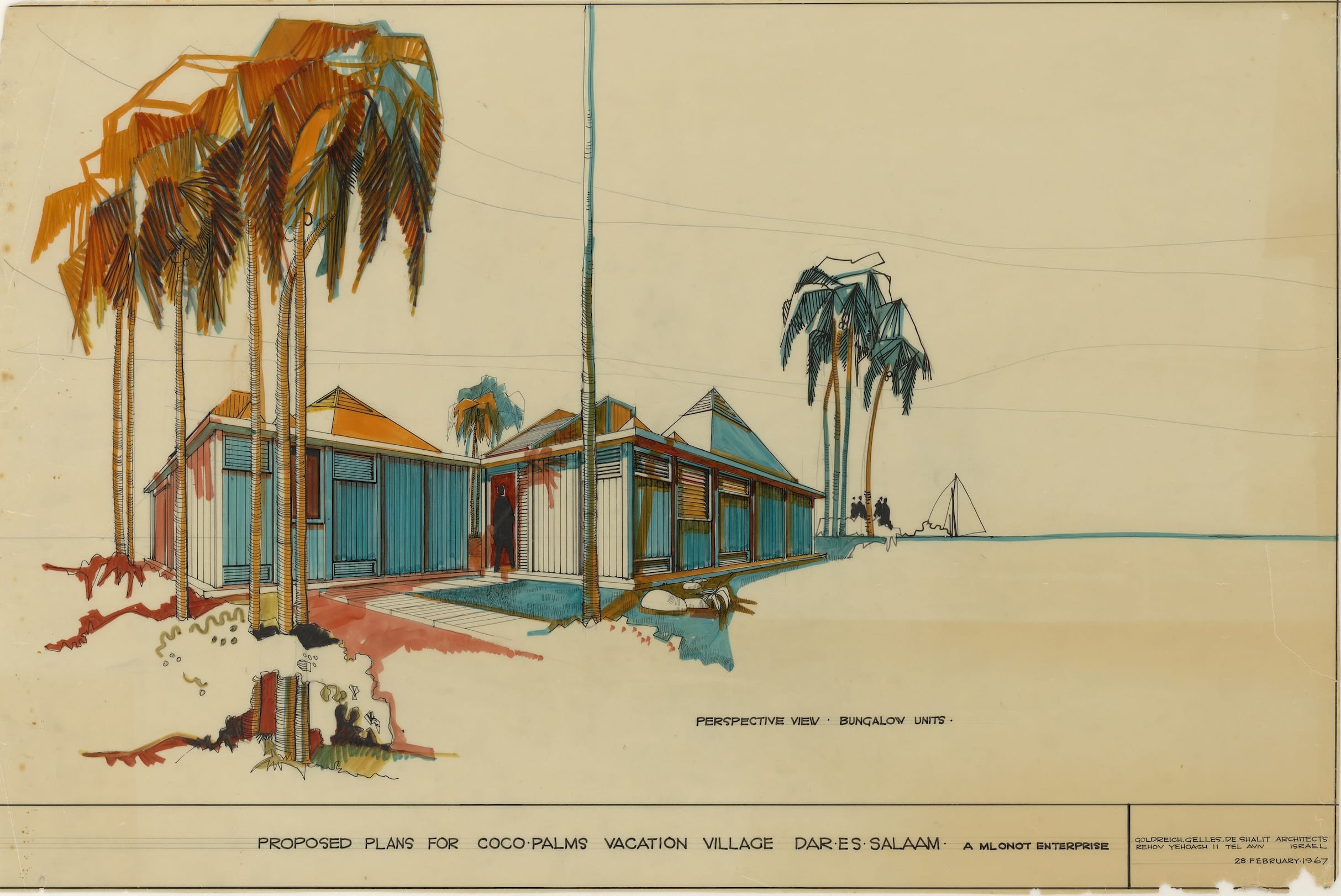

‘Coco Palms’ Holiday Village (1967)

The 1967 commission for ‘Coco Palms’ in Tanzania followed a run of domestic successes, notably the Red Rock Hotel in Eilat (1965–67). It marked the attempt to transfer the resort expertise they had developed in Israel to an African market. The scheme combined a central public area with fifty pairs of bungalows spread along the Indian Ocean shore. Plans and perspectives reveal the project’s clear modularity with identical guest units allowing phased construction; response to tropical climate with pitched roofs and ventilation openings; and connection to the landscape with the public wing serving as a transparent hinge between palm grove and beach. A deeper biographical element existed here: Dar es Salaam was where Goldreich had fled to after he escaped from prison in South Africa. Sadly, the scheme was never realised.

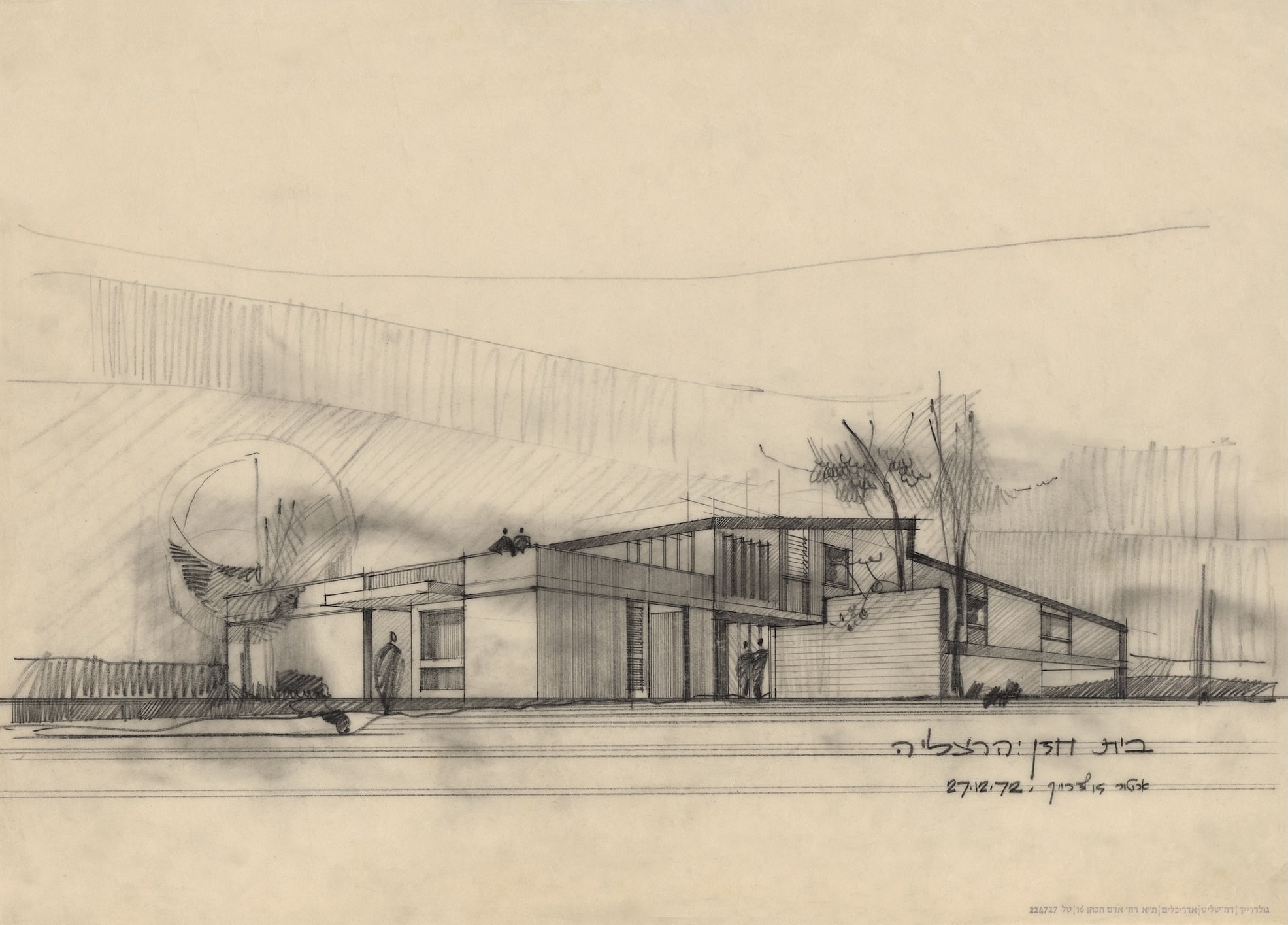

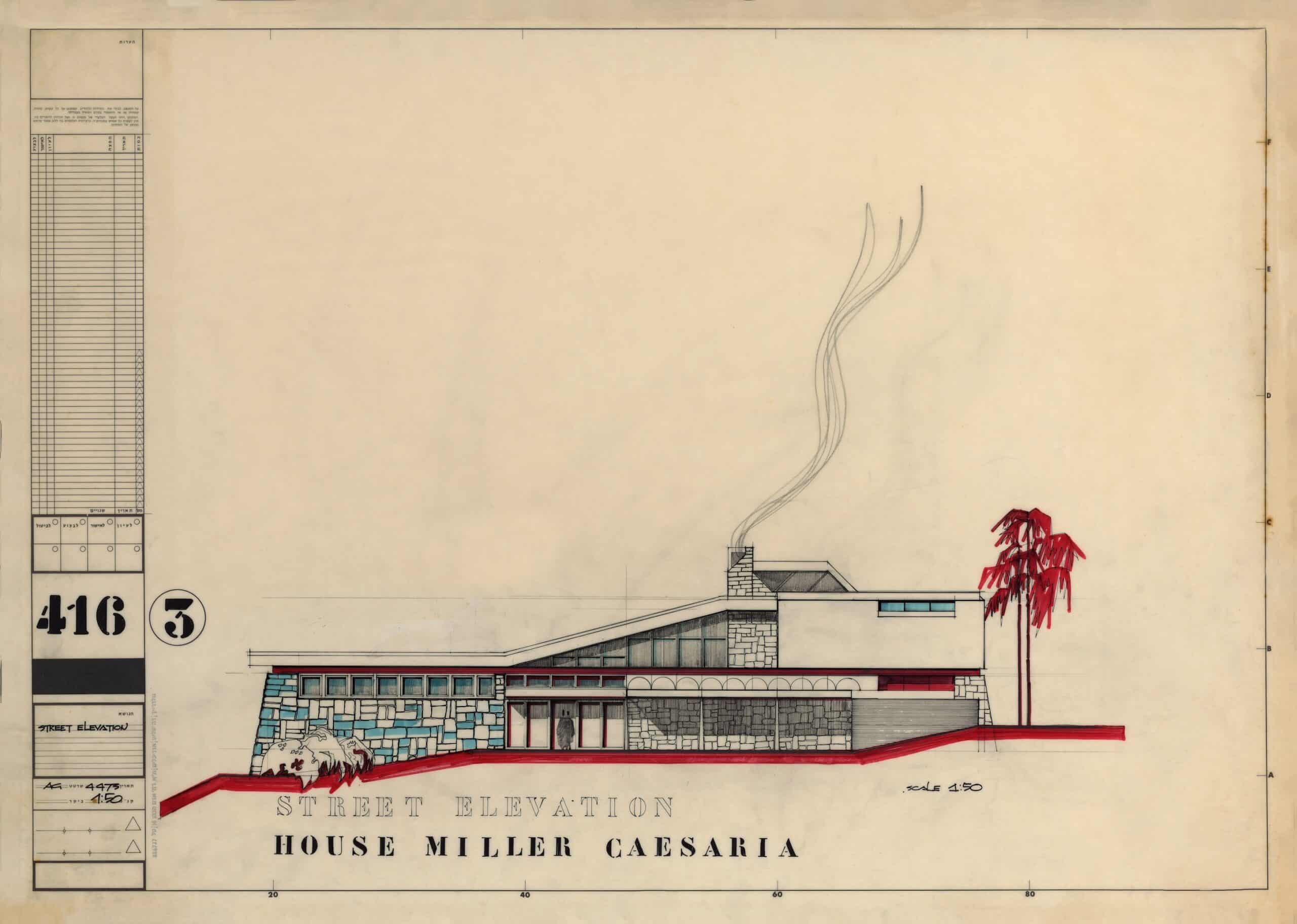

Hazan and Miller Houses (1972–3)

Sadly never built, both the Miller House (1973) and Hazan House (1972) exemplify Goldreich and de Shalit’s humane, climate-responsive modernism. These private residences shared a ‘total design’ ethos: integrating architecture with furniture and fixtures; modernist geometry tempered by climate, with volumes that were shaded and cross-ventilated rather than excessively glazed; and material honesty expressed through fair-faced concrete and local limestone outside, with timber and terrazzo inside. These projects represent Goldreich and de Shalit’s mature modernism, with elements serving as prototypes for later works and embodying their progressive design philosophy.

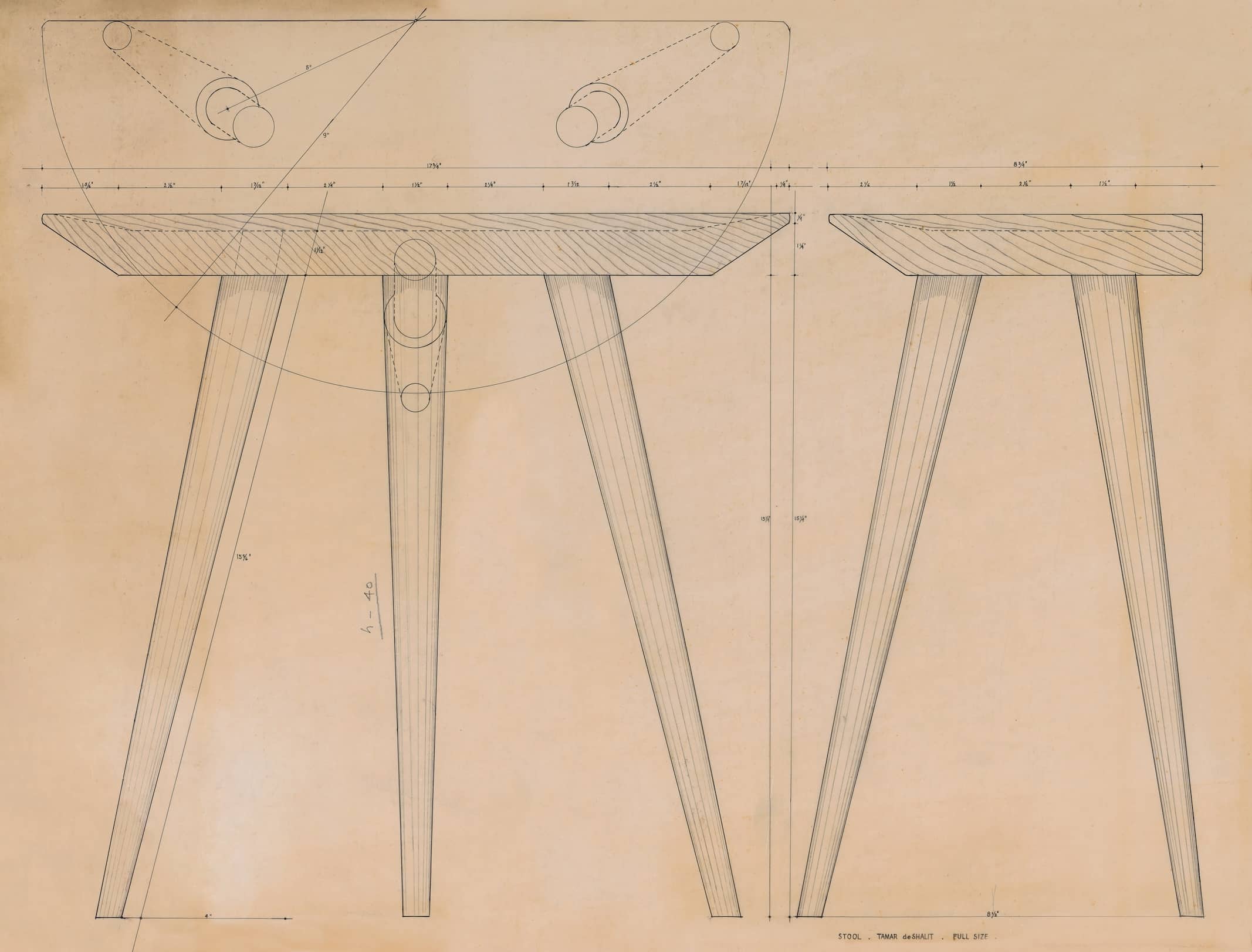

Central Stool (1951); reimagined by TAMART (2024)

The three-legged Central Stool was originally designed in the 1950s by Tamar de Shalit during her studies at London’s Central School of Arts and Crafts. The smooth, half-moon, turned wooden form features three tapered legs and crafted mortise and tenon joints. The piece functions either as an occasional table or a stool. The stool is freestanding, but its straight side can align with the wall which becomes a backrest, and if paired with another stool, it forms a fully circular side table. In contemporary settings, the Central Stool resonates: its economy of means, multifunctionality and clarity of line align with today’s desire for adaptable, sustainable objects. Whether supporting a guest’s drink, stacking magazines beside the sofa or offering perch space in a hallway, it excels in quiet usefulness. At 450mm high, the seat encourages informal conversation, its gentle scoop cupping the sitter without dictating posture, proving that a student experiment can endure. The original stool and this detailed plan and elevation, drawn by Tamar, are found in TAMART’s showroom.

*

Amos Goldreich is an architect and the founder and creative director of Tamart. Learn more about how Tamart has reimagined Tamar de Shalit’s and Arthur Goldreich’s designs in this short film.