The Work of Ernest and Esther Born: Models for the City House

Ernest and Esther Born trained as architects at Berkeley in the early 1920s and worked with great distinction in all aspects of architecture and the allied arts, from graphics and illustration to display design and architectural photography. This project marks one of their first endeavours on returning to San Francisco in 1936, after ten years in Europe, New York and Mexico (where Esther’s 1935 photographs pioneered observations of the new architecture).

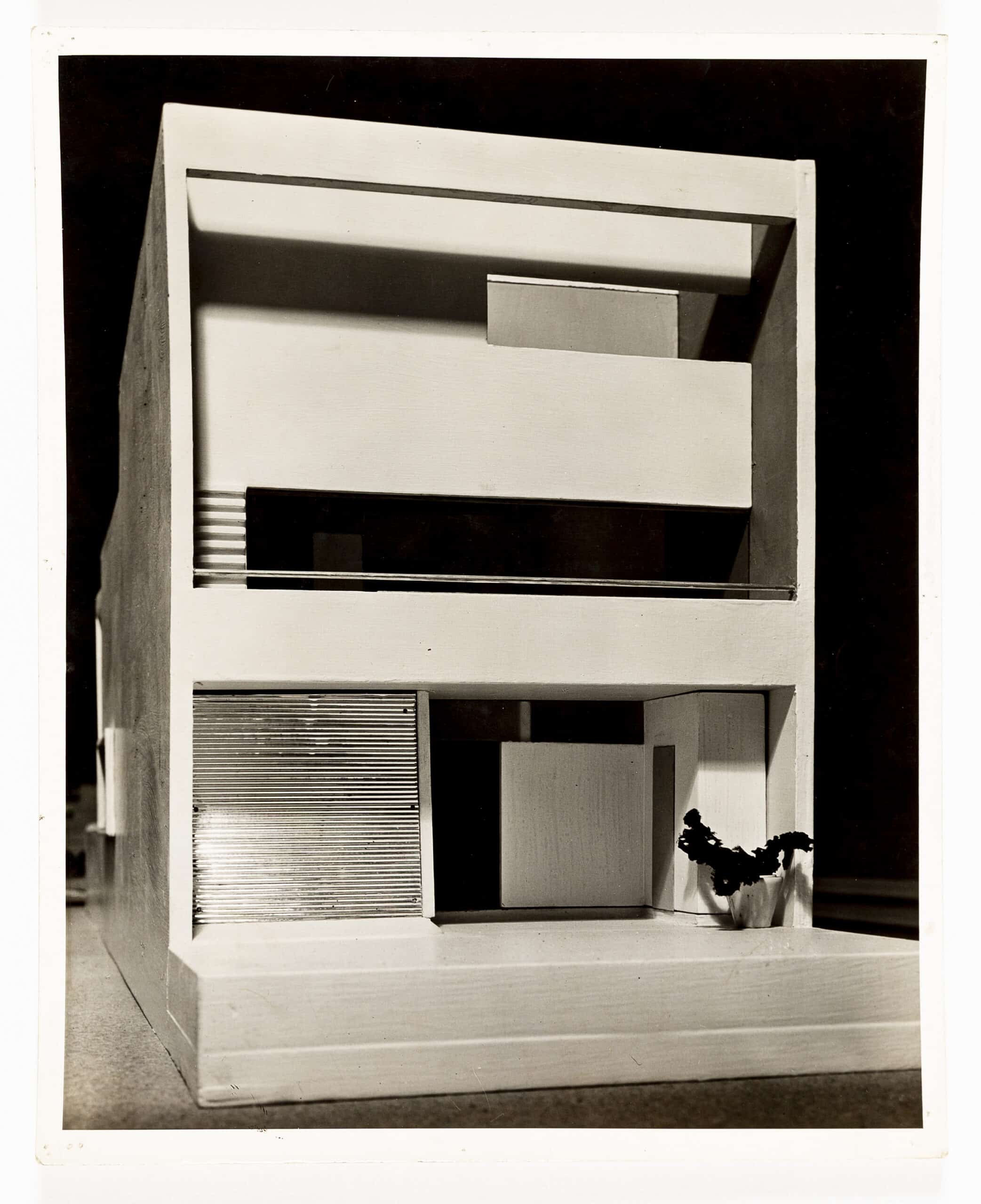

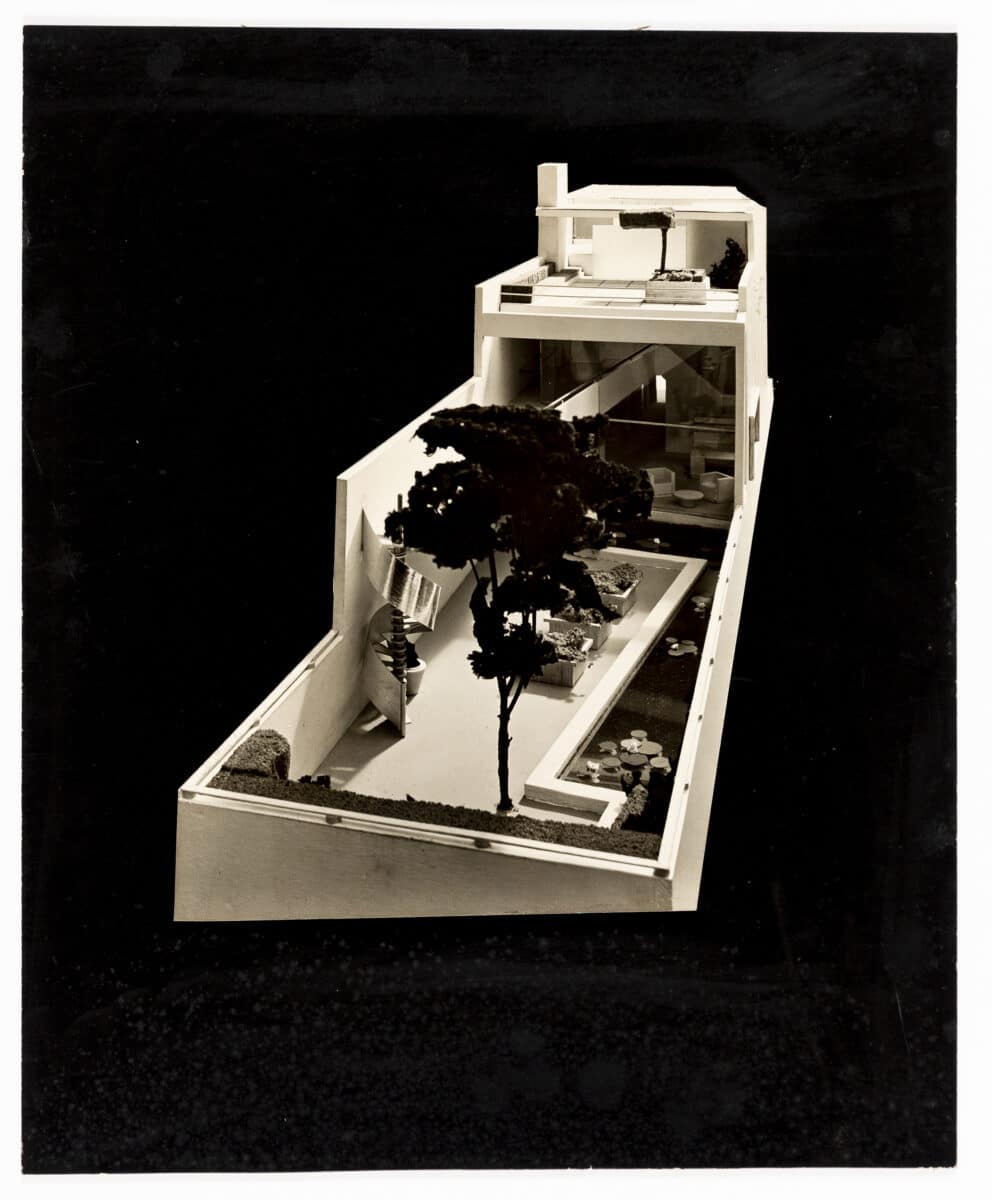

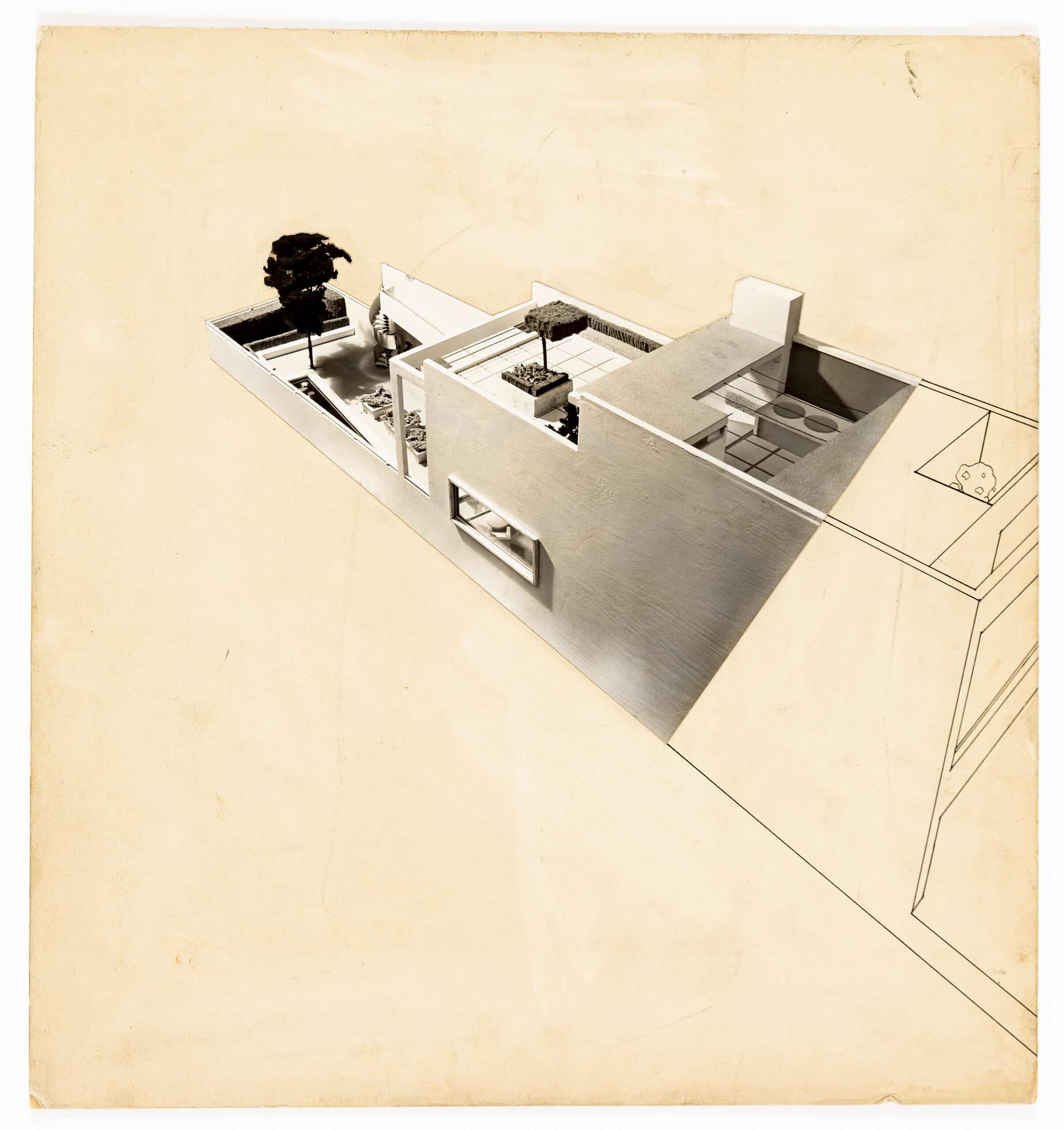

Late in 1936, Ernest Born returned to San Francisco to set up practice there. Almost at once he began work on an experimental ‘city house’ with the landscape architect Thomas Church – his classmate at Berkeley – and the architect and model-maker Carl Bertil Lund, who had come from New York to work as Born’s associate. Designed to the edges of a narrow 25-foot lot, this was an extraordinarily radical approach to rethinking the row house as an independent dwelling, integrated with a highly structured private landscape. The plans compress the structure at one end of the site to steal space for the outdoors, and stack the enclosed spaces on three levels so that they all lead out to terraced living. The architects described it as comprising two simple units: a living and eating space; and a space for ‘retirement, privacy, sleeping’. But those zones are organised vertically. Thus kitchen and dining share a mezzanine, and a spiral stair links the kitchen down to a service entry below and up to a quiet sitting space, sleeping porch and study on a partly sheltered roof.

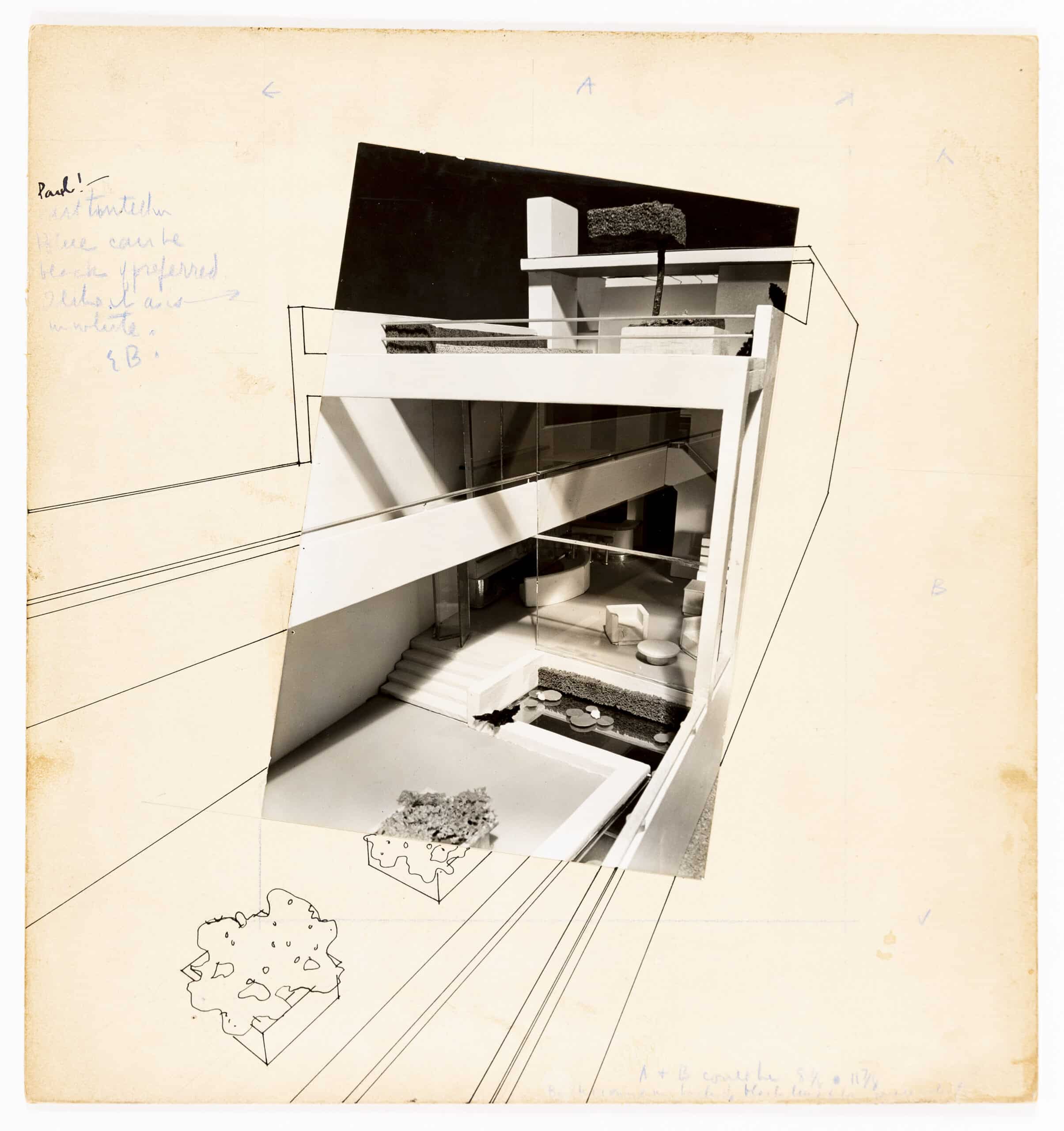

The two most remarkable features are the window wall and mezzanine. As Ernest saw it, ‘the great area of glass acts neither as wall nor window but merely as physical agent for the control of indoor temperature’. The mezzanine is essentially a bridge that tapers from room width at the kitchen and dining end to a narrow elevated balcony as it moves far into the open above the garden, ending in a circular stair to drop down. As they expressed it, the effort was to ‘eliminate hard and fast separation’ between zones and between living indoors and living out, and the bridge was imagined as a visual device that acted ‘strongly to splice the outside and inside together’. Church stated that the garden ‘has nothing to do with gardening’ and developed it as an abstract sculpture – using exactly the same materials as in the construction of the house, and following similar proportions. But where the thesis of the house was ‘space’, they described that of the garden as ‘form’, precisely the relationship Born had sought a little later in a magazine study for an indoor-outdoor bedroom. In that, as in its fascination with bridging space and moving people through changing levels, the Model City House and Garden establishes the dialogues that would govern all of Ernest’s architectural work to come: between space and form, architecture and art, the shape of things on the ground and the vistas of their surroundings.

Ernest and Esther Born chose means just as radical to represent the proposal, collaging model photographs with Church’s drawings, experimenting with a black background, and using both eccentric camera angles and off-centre placement on the page to make the unusual logic of the plan clear. Submitted to the first exhibition of landscape architecture at the SF Museum of Art early in 1937, the scheme won first prize. Publishing the project with illustrations of extraordinary boldness in the Architectural Forum in April that year, the editors called it ‘so brilliant a solution of a […] common problem that it is here offered as an example of the potentialities of the architect who is willing to think clearly and creatively’. It is hard to imagine this adventure in design for living coming without the Borns’ experience of the Rivera, Castellanos and O’Gorman studios in Mexico.

Extracted from Architects and Artists: The Work of Ernest and Esther Born, published by The Book Club of California. You can listen to Nicholas’s talk about Ernest and Esther Born here.