Two Way Traffic: Japanese Woodblock Prints

One of the great enigmas of ukiyo-e – Japanese woodblock prints of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries – is the anachronistic intrusion of Western drawing into an apparently closed world; that the sophisticated culture of Edo (now modern Tokyo) seemingly closed off its borders since the Middle Ages.

The widespread view of an isolated Japan is not quite as accepted as it was a few years ago. In fact, Europeans had been trading with Japan since the 1540s; first the Spanish, then the Portuguese, and finally the Dutch. It was rapid Christianisation (the Latin traders bought with them Jesuit missionaries) that was most troubling to the ruling shogunate, rather than the idea of foreign trade. Christianity was outlawed and, crucially, it was the protestant Dutch, exporters of European Enlightenment, who first revived significant relations with the Japanese. This was a necessary exchange; internal strife in Ming Dynasty China meant that trading relations with the East were difficult. European trade with Japan became an essential source of luxury goods for the Dutch and a new export market for the Japanese.

Many goods from Enlightenment Europe stressed technological advances, particularly optical instruments. Of these, stereoscopes and mechanical devices, European vues d’optique, were popular. In the 1770s, Utagawa Toyoharu (the artist and founder of the great Utagawa School of printing) started to design miniature cityscapes and printed views based on European originals used in hand-held optical devices. These prints were rapidly developed into large, Oban-sized woodblock prints. The result, uki-e print or ‘depth pictures’. This phrase was similar to ukiyo-e, ‘pictures of the floating world’. But whereas ukiyo-e celebrated the fading metaphysical world of poets and dreamers, uki-e looked forward to the bright materialism of Western enlightenment.

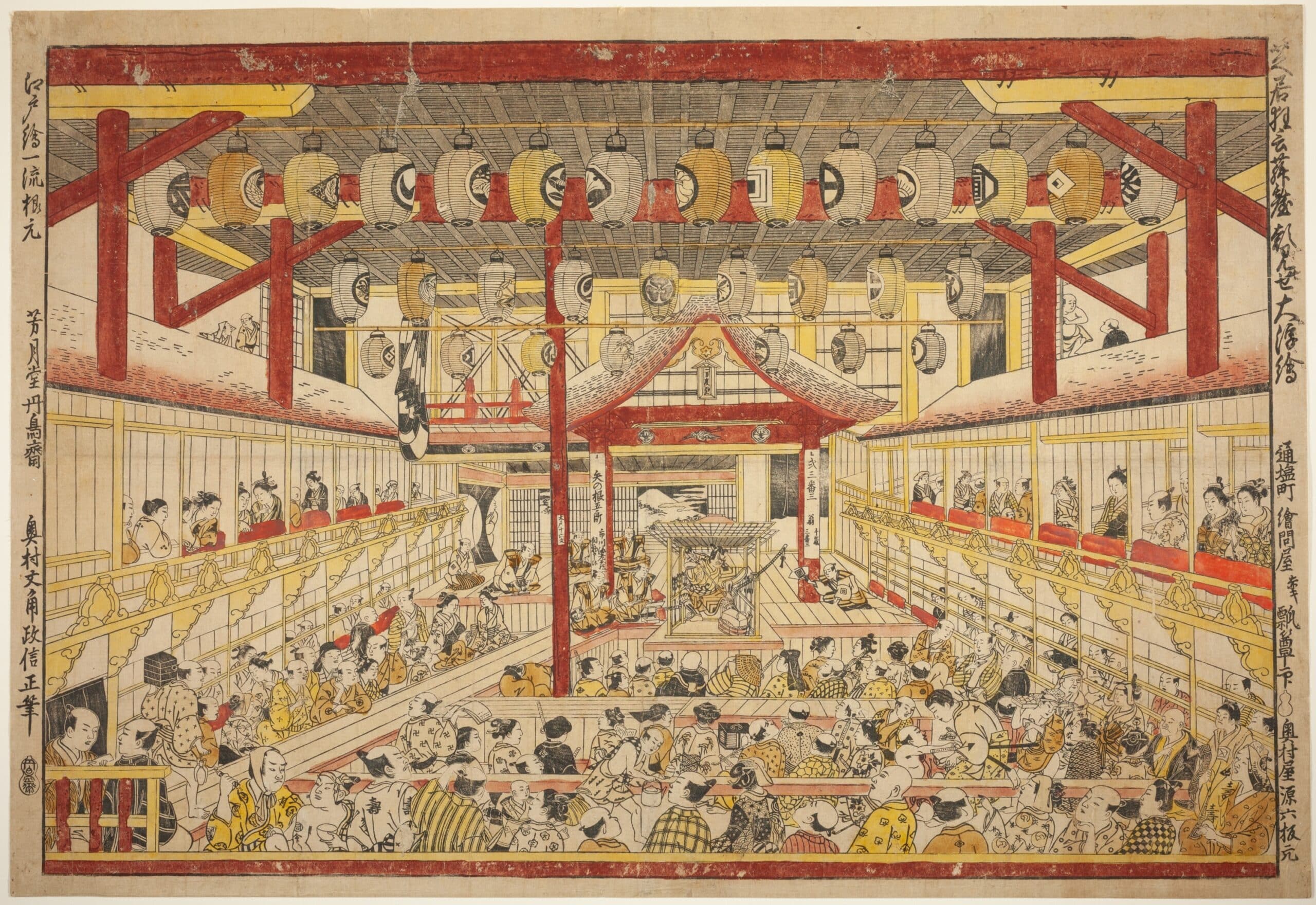

Okumura Masanobu’s Large Perspective Picture of the Kaomise Performance on the Kabuki Stage shows real mastery of the Western style of drawing. Compare this with a print by the same artist five years earlier, Enjoying the Evening Cool near Ryogoku Bridge, which combines knowledge of perspective in a grid-like structure with a purely Eastern style of drawing for the background. These prints are useful examples of the rapid adoption of new styles in the middle of the eighteenth century.

But there was more to the Japanese in the manner of perspective than usefulness or practical application. Held within the straight lines and vanishing points was an exotic otherness; literally a window into another world. Perspective drawing had developed in Italy over a period of centuries, for the Japanese, the drawing style came upon them fully formed and without precedent; so much so that it is possible that its unfamiliarity was hard to decipher at first. An innovator of western styles was Shiba Kokan, who wrote a treatise on the subject, which among other things advised:

There is a correct way to look (at western pictures), and to this end, western pictures are framed and hung up. When viewing them, even if you only intend a quick glance, stand full square in front. The western picture will always show a division between sky and ground (the horizon line): be sure to position this exactly at eye-level, which generally speaking, will entail viewing from a distance of [approximately 180cm]. If you observe these rules things shown near at hand and things shown far off – the foreground and background – will be clearly distinguished and the picture will appear to be the same as reality itself.

Note how these ‘instructions’ imply that the realism of the new pictures needed to be taught, much like magic eye pictures of the 1990s.

Japanese images, most commonly woodblock prints, exist in a very different space to their Western equivalents. Eighteenth century images of Japanese women or actors, or other popular subjects, are set against an immaterial background whose equivocation can suggest at times a painted backdrop or screen; or at others a series of related ideas: a bridge, a mountain, trees, etc. This lack of horizon allows for a greater breadth of view. Japanese drawing space, therefore, leaves a lacuna between the intention of the artist and the expectation of the viewer. No such thing exists in Western drawing, where it is the responsibility of the artist to be unequivocal. In Japanese drawing, reality is not fixed. This is a manifestation of its wider culture. Japanese art reflects the philosophy of Buddhism and Shintoism; the Renaissance perspective inhabits the neo-platonism of its time, the ordered and material world of solids.

The collision of these two traditions led to some startling anomalies, especially in the period when the opening of trading relations allowed more and more Western engravings into Japan.

The title of this print attributed to the Japanese artist Utagawa Toyoharu is, surprisingly, A Franciscan Monastery in Holland. Whilst Japanese artists could understand perspective, they were less likely to be able to translate the titles – if indeed there were any. A universal feature of Japanese prints is the combination of the image with decorative cartouches, each carrying formal information such as the title of the print, the series title, the publisher, the artist, the date, and so on. Sometimes, helpful notes next to each character might suggest the name of an actor or a historic figure. These intrusions into the visual realm were very much a part of the considered aesthetic of the whole piece. To the Japanese, the barrenness of information would have been uncomfortable, and so fictional titles were attached to foreign subjects, this print being a good case in point.

The print actually represents the Forum in Rome. I found what I suspect was Toyoharu’s inspiration for the print in a series of engravings by Johann Sebastian Müller. Müller and his brother, Tobias were scrupulous architectural and botanic engravers working in eighteenth century London.

In what must have been a commissioned project, Müller created a set of engraved copies of various painted cityscape fantasies of Rome by the genre painter, Giovanni Paolo Panini. It is clear that the Japanese artist used information from two of Müller’s prints on roughly the same subject. It is not clear why he took it upon himself to amalgamate a work from several different sources: Trajan’s Column is on the right and the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina is on the left from the prints shown above.

Panini was a very successful vendutisti, or view painter, and much of his output were capricci, views of ancient Rome for the tourist market. These were skillful assemblages of the great ruins of Rome made into one fanciful view. They were popular among British Grand Tour visitors and were then presumably copied by Müller in his sets of engravings.

The first painting by Panini seems to be the design from which Müller’s second print was derived; however, a further complication is added by the more or less unknown painting above attributed to ‘School of Piacenza’ by the Dorotheum Auction House in its recent sale in 2021. It is in fact a mysterious painting previously attributed to Panini, last seen at Bristol Auctioneers, Frost & Reed, in 1928. Note how the proportion of this second version is closer to Müller’s engraving. For completeness, below is another painting by Panini of the scene, this time with the Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius which appears in the first of the Müller engravings.

Ironically, these views were fictional. Just as Panini bowdlerised the Roman cityscape for convenience, so did Toyoharu and other Japanese artists with their cut-up approach to Müller’s faithful copies.

It is interesting to plot the export route by which the classical glory of Rome travelled from Italy to London through Panini’s paintings into Müller’s engravings, which presumably found their way to Holland, thence the circuitous route to the only port in Japan at Yokohama and then possibly clandestinely to the Edo (Tokyo) studios of Utagawa Toyoharu. By this time even the stones themselves had lost their familiarity.

Toyoharu almost certainly wouldn’t have seen any other stone building than the rubble ramparts of Edo castle. Consider the impossibility of rendering columns and capitols, pediments and statues in such unfamiliar materials, or indeed the canals of Venice (see below, titled; The Bell which Resounds for Ten Thousand Leagues in the Dutch Port of Furankai). Unable to translate the actual title, Toyoharu chose to use the scant knowledge that he possessed about foreigners, first that they were Dutch, and second that they were priestly – this second guess being dangerous at the time given Japan’s deep hatred of Christianity.

These entertaining attempts at a new style were not simply diversions in the backwaters of Japanese print art; they suggest wider cultural discontent. The interest in foreign cultures coincided with the rapid explosion of chōnin, the newly affluent merchant class of Edo. Edo was the most populous city on earth at the time, but the ruling Tokugawa family feared the waning of their position and made attempts to restrain what they saw as Western decadence, often by means of eccentric punitive laws. These exotic prints achieved something fundamental, they opened a window onto a different reality and they proposed new ideas from the Enlightenment. These ideas embodied science, optics, architecture, technology and intellectual freedom. What seemed exotic to western eyes – the world of geishas and samurai – to the Japanese was shaming and backward. When the revolution came in 1864 it established the Meiji Emperor with a vigorous campaign of foreign trade and enlightenment. These quotes from the new constitution give a flavour of that time:

Evil customs of the past shall be broken off and everything based upon the just laws of Nature.

Knowledge shall be sought throughout the world so as to strengthen the foundations of imperial rule.

Knowledge sought and the customs of the past broken off. How well these vows describe the shift in drawing style from the poetic ukiyo-e of Edo to the ‘enlightened’ uki-e of the new Japan.

Alex Faulkner is the director of Toshidama Gallery.

Note

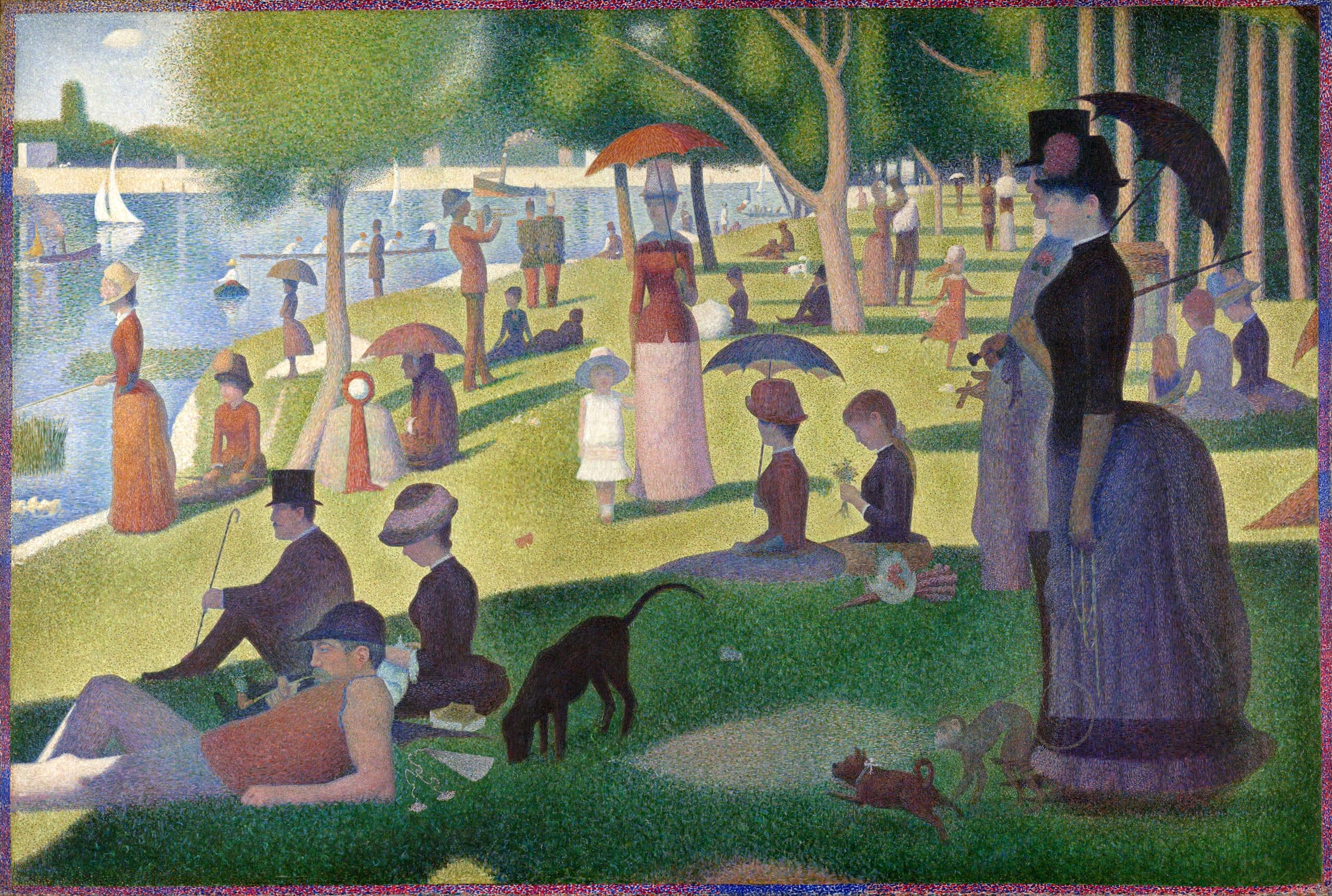

If there should be any doubt about the later and far greater influence that Japanese drawing in its turn had on early modernism, I leave you with two images, one by the Japanese artist, Utagawa Toyokuni I; the other, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte by Georges Seurat, a hundred years later.