Mother of All Drawings

The very first attempts of humans to express their thoughts can be seen in prehistoric cave paintings. From these rudimentary markings to modern-day coding, the human race has evolved to acquire many skills. Still, none of us are born fully equipped with this skillset; we must repeat this process of learning in a lifetime.

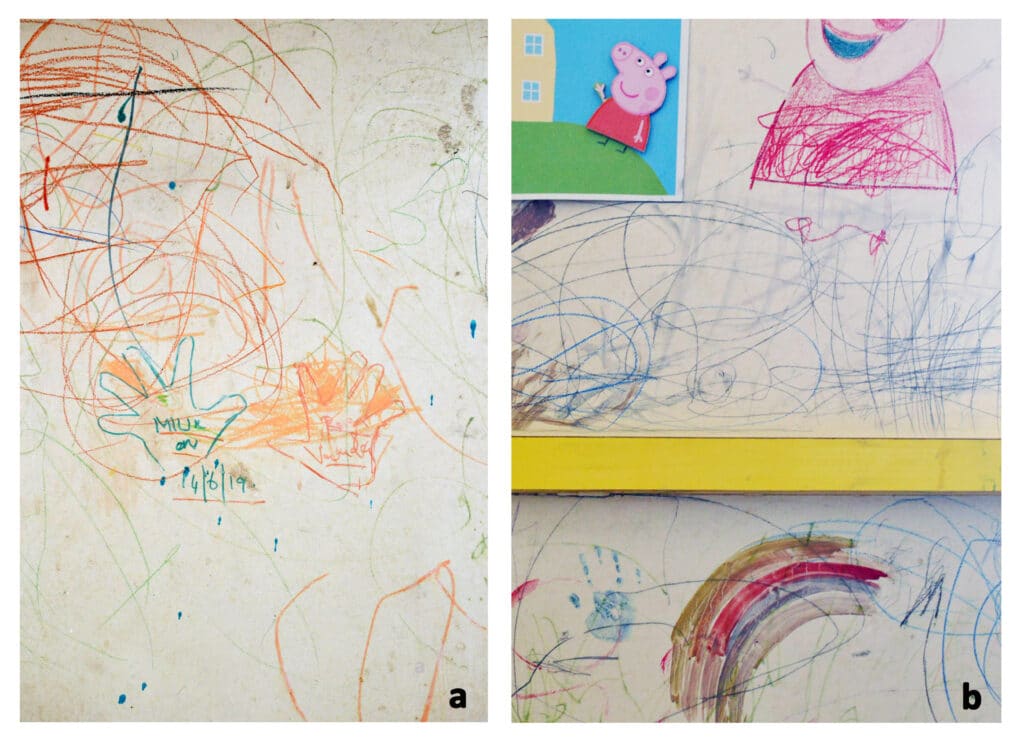

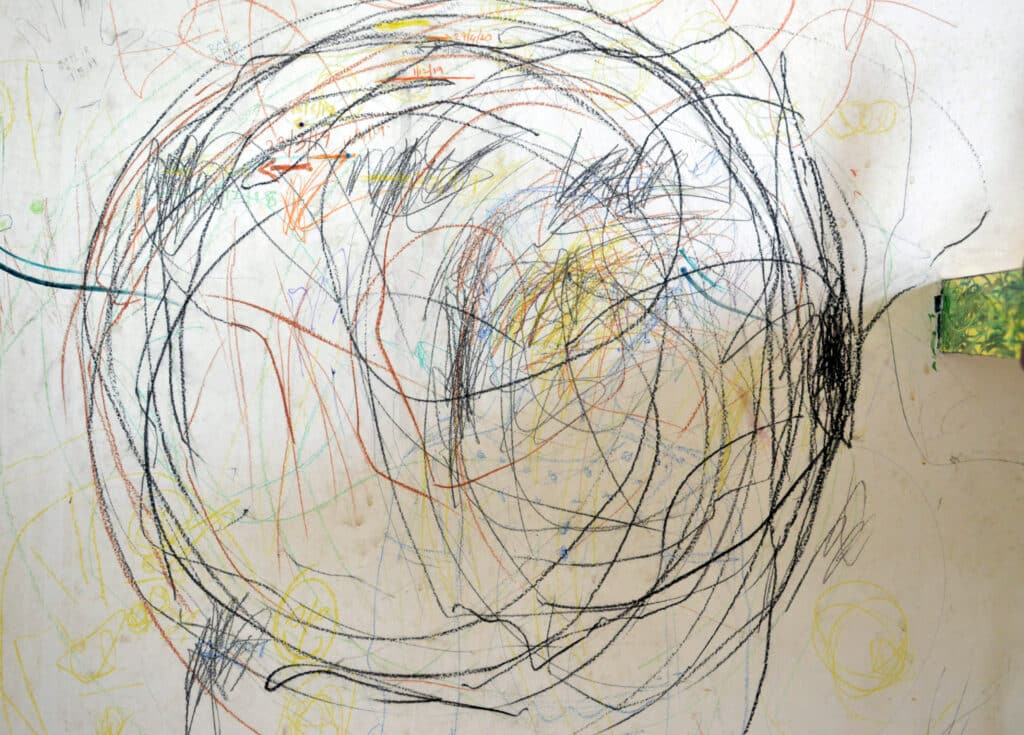

At the age of three-and-a-half, my daughter has covered almost the entire reachable wall surface of our room in drawings. These walls were empty before her birth. Her drawings are the drawings in these images – the first way of expressing herself through a medium. As an architect, the spirit behind her drawings is a constant source of inspiration, compelling me to continue with what I did last week, or what I did yesterday. Her playful approach to learning helps me see life and design from a unique child-like perspective. Some might call her drawings scribbling, but I like to call them the ‘mother of all drawings’, for every great work starts with doodles like these, hiding a seed of infinite growth. Here the process of her drawing is evolutionary.

The evolution of the mural began the first day she held a crayon (when she was less than 18 months old); to a brush, a sketch pen, and to now a pencil – the preferred tool in kindergarten. The room has become a dynamic collage, with us, our lives, and day-to-day activities existing alongside the drawings. When we look at each wall separately it is sequenced like a sketchbook, with walls instead of sheets of paper. The drawings are neither complete nor incomplete, and she might improvise by adding another layer with any medium within arm’s reach. I am the proud owner of all her drawings. It is not a sketchbook that you have to find and open to see. I open my eyes to this every day.

Her enthusiasm encouraged us to join hands and explore too. While she doodles I draw her favourite characters and her father records her growth. She is too impatient to turn the page or follow instructions. And she doesn’t understand why she has to work on a small piece of paper with a particular shape in playgroup when she has the walls at home without limitations.

Seventeen years ago, on my first day of architecture school, a professor asked our class of 45 students who could draw a circle freehand. I didn’t understand why this was asked at the time. It could have been to see who among us was confident enough to say yes. But even the most talented students avoided the challenge. Later, I searched online for tricks and hacks to draw a circle without a compass.

When our daughter was less than three years old, she could firmly grip a crayon and create an almost perfect (more than perfect for me) circle. Given the freedom of expression and no fear of impressing others, a three-year-old could draw it with ease. She herself did not know the depth of what she had done. Children’s drawings are works of astonishment without the framework or boundaries of education. This limitlessness is what we adults should learn from children. The drawings of Zaha Hadid have always left me with a sense of awe. I would spend hours in the library going through books about her and her work. One day, I saw a similar strength and dynamism in my daughter’s strokes, always looking to untested waters.

Teaching architecture is still a continuous learning process for me. I have seen many extraordinary talents in the past decade through teaching, but there are very few drawings that have moved me.

Some time ago I visited a world heritage site close to my city with my first-year college students to sketch. There, beyond the fence of the heritage site stood a small girl no more than five years of age. She was intrigued by the way the college students were observing and sketching. She ran and got a piece of board lying close by and borrowed tools from the students across the fence and drew an abstract of what she could see. How aesthetic was the drawing? I don’t know. Did I like it? Of course! It is the spirit behind the drawing that awes me, even when recollecting it a decade later. There have been and still will be many students who can outsmart me, their teacher, and create all types of inspiring drawings. I get satisfaction from their work. Being a teacher is a wonderful experience in the field of architecture. But when I pin down my true inspirations, it was the girl with very limited resources who had the zest and courage to run rings around college students, and now my daughter, who has changed my outlook on exploring and expressing myself.

Deepiga Kameswaran is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Architecture, Dr.MGR Educational & Research Institute, Chennai India. She believes that ‘teaching is a continuous learning process’.

This text was entered into the 2020 Drawing Matter Writing Prize. Click here to read the winning texts and more writing that was particularly enjoyed by the prize judges.

– Alberto Ponis