Charlotte Skene Catling: The Dairy House

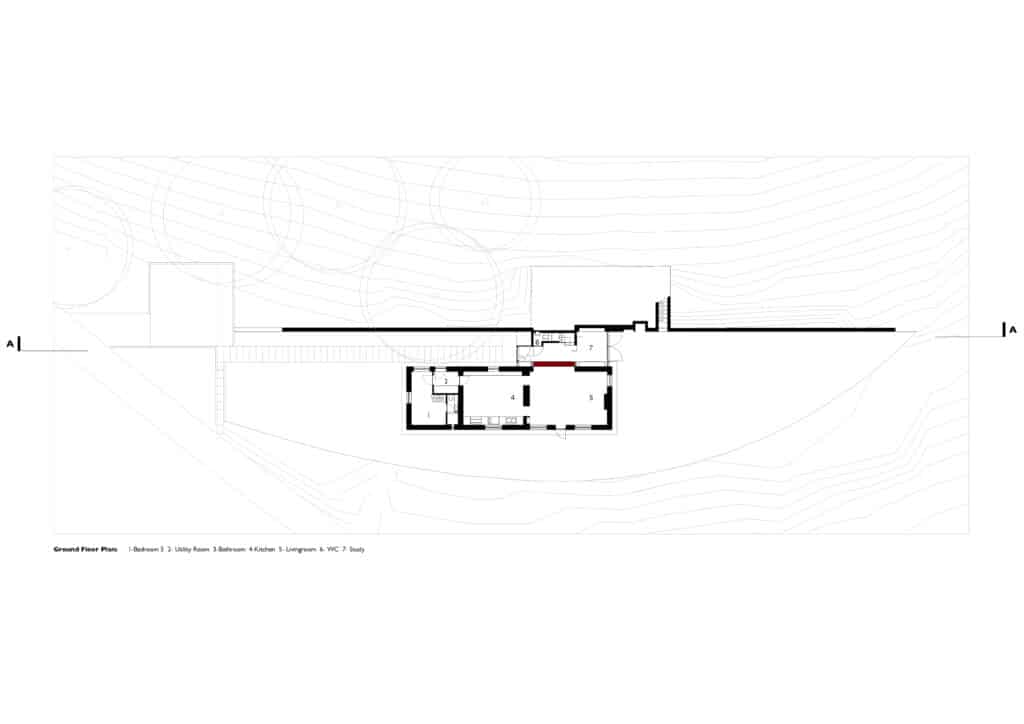

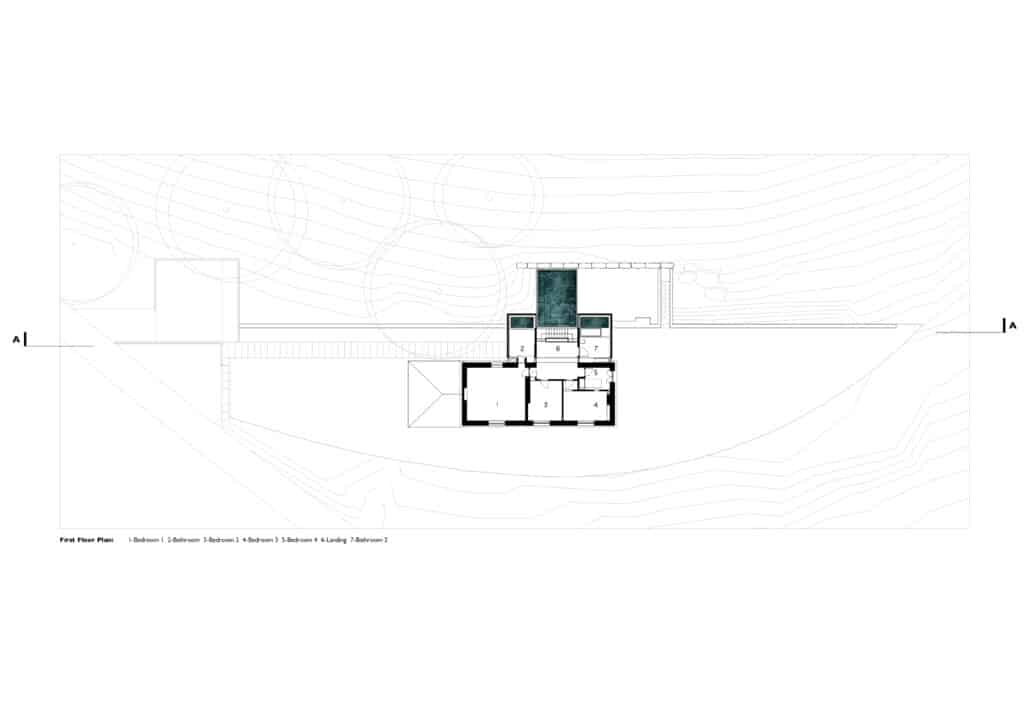

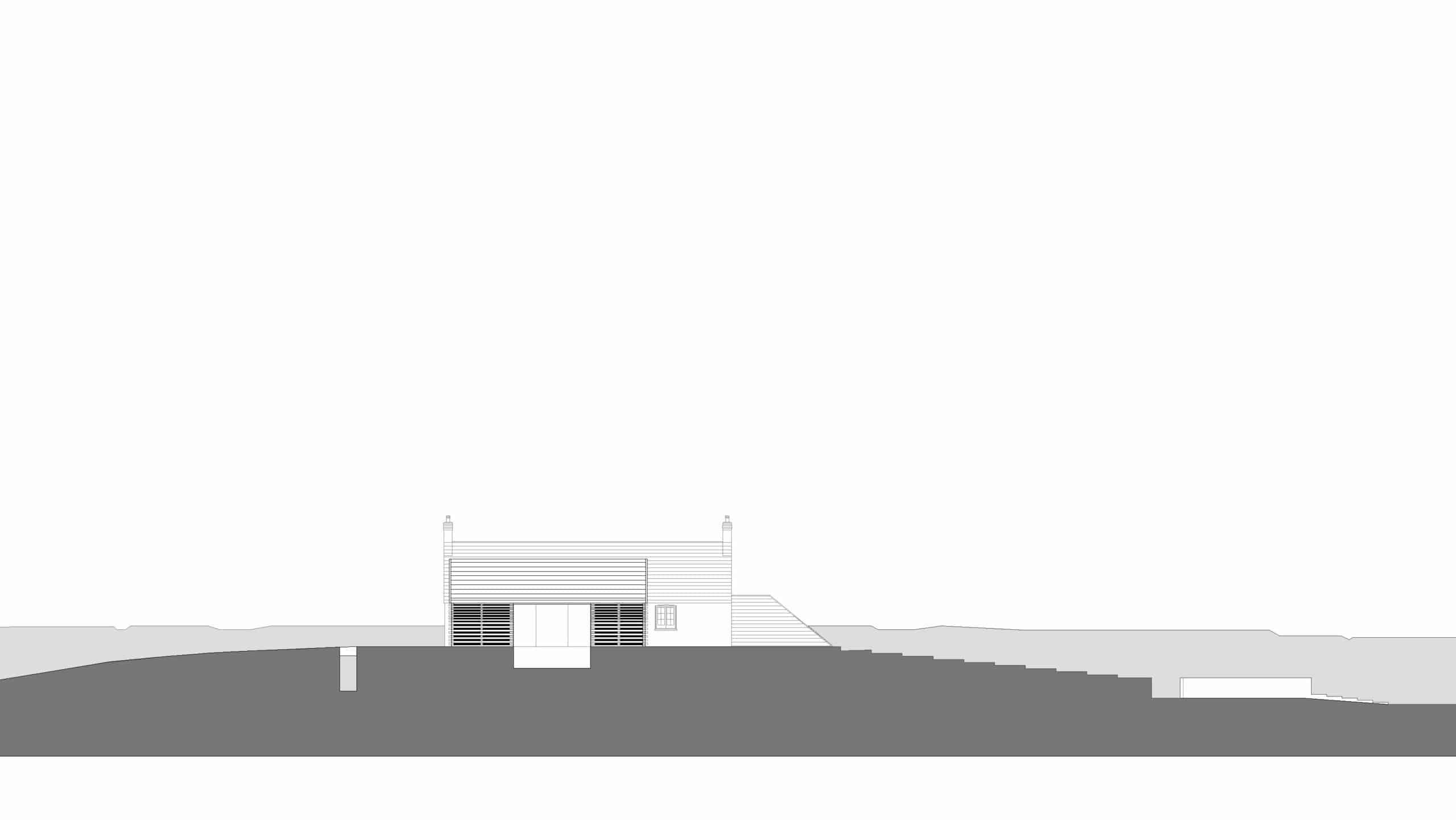

This project involved the enlargement of a nineteenth-century masonry dairy house built by the owner’s great grandfather for the estate’s cheesemaker. The addition fills a narrow space dug into the hill behind the existing house providing additional bedrooms, bathrooms, and more generous circulation spaces. The building sits in an 850-acre estate in Somerset, and the addition was to be discreet, invisible from the main facade of the existing structure and ‘undesigned’, a natural extension of the old building.

The architect refers to the project as a dogtrot, [1] the vernacular American building type consisting of an open centre passage—for the dog to trot—flanked by two enclosed living spaces. She also refers to it as a ‘folly’. The addition can be read as a dogtrot in its recessed centre, in plan, emphasized by the void of the pool and framed by two rooms; it is also, perhaps, a three-dimensional dogtrot since the ground floor is a void framed by the new building above and the ground because the addition bridges from the old house to the hill. The dogtrot/folly pairing suggests a fantasy of the simple life but also a fantasy of escape and freedom. The addition has the archetypal form of a house, or a barn, and it looks like it could be older than the building to which it is added. At the start of the project, Charlotte Skene Catling was inspired by seeing timber planks drying nearby; the raw planks were separated by spacers for air circulation. This generated the idea and aesthetic of the extension.

Glass ‘boards’ would be layered in the same manner in the new design, becoming thicker towards the base to reinforce a sense of weight and rustication. The new building envelope is porous to light; its form is old, but its concept and execution are new.

Textured, weathered wood boards, left rough on the outside but planed smooth on the inside, contrast with the rigorous precision of the glass, itself rough on the outside but polished on the inside. The apparent simplicity of the dairy—a primitive hut—and its position as a folly in the woods suggest an escape from the formality of the estate.

The glass receives the same level of care as the wood planks but is produced industrially by Pilkington, with a high degree of precision— a super technological product; it is installed with gaskets and caulking to resolve the different dimensional tolerances between glass and timber in a system developed through trial and error by the architect and a local craftsman. In three areas, the glass ‘boards’ are turned vertically as narrow horizontal windows.

Glass is the interstitial material, but it is at the core of the project’s conception; ideas of transparency and reflection associated with glass animate the project. There is the reflection of the two symmetrical rooms in the pool, there is also the laminated glass-and-timber wall reflected in the bathroom’s mirrored wall giving the sense of an infinite forest.

In the Dairy House, a modest, timeless vernacular form has been transformed into a highly refined combination of dark and light, old and new, antique and modern, rough and refined. What is the relationship of this design to memory? Obviously, the simple barn form speaks for itself and numerous other ‘un-designed’ buildings, modest shelters, countless vernacular buildings. We know these buildings in our heart. They are realized in different cultures in different materials, but the simple roof form and the material, cultural, connection to ‘place’ is always there. The introduction of highly crafted, highly engineered glass and the juxtaposition of this modern industrial product with traditional materials and construction transforms the traditional form into something else: a sensual, highly intellectualized, object, in the present. The architect uses palpable qualities of craft: specific individual boards harvested and dried in place; their texture and relationship to the glass display the act of making. It is all local, derived from tradition, and all manual. What appears undesigned is highly designed, what appears traditional uses re-invented traditional practices combined with modern industrial processes to achieve a traditional object of the mind or perhaps a fantasy of contextualism.

Notes

- All Skene Catling quotations from Author’s interview with Charlotte Skene Catling, 20/06/2019.

This text is excerpted from Material Transfers: Metaphor, Craft, and Place in Contemporary Architecture, by Françoise Astorg Bollack. To purchase the book, click here.